“A Serious Man” Revisited

I don’t have much use for light comedies, but I love dark ones. Thus I have been a fan of the Coen brothers ever since their first movie Blood Simple, which I regard as a masterpiece. But not all of their movies succeed. The Coens are at their best when they are working with tight and ingenious plots. Blood Simple, Miller’s Crossing, Fargo, The Hudsucker Proxy, and No Country for Old Men (no comedy that) come immediately to mind. However, when they stray from tight plotting, their movies tend to fail. But one still has to grant that films like Barton Fink, The Big Lebowski, and O Brother, Where Art Thou? are at least interesting failures.

At first viewing, I thought A Serious Man was just another interesting failure. But my mind kept coming back to it, like a tongue seeking a sore tooth, until I broke down and watched it again. This time, I think I got it. And I like it. I am going to summarize pretty much the whole story, so if you have not watched it, bail out here.

A Serious Man consists of two apparently unrelated stories. The first is only a few minutes long. It is set in a 19th century Polish shtetl. The dialogue is entirely in Yiddish. One snowy night, Velvel (Allen Lewis Rickman) returns home from selling some geese and tells his wife Dora (Yelena Shmuelenson) that on his way home, he met the Reb Groshkover. Dora says that this is impossible, for Groshkover is dead. Velvel must have met a dybbuk, a demon that possessed the body of the dead rabbi. Just then, there is a knock at the door. Dora is horrified. Velvel has invited Reb Groshkover in.

Dora does not waste time with pleasantries. She accuses Groshkover (Fyvush Finkel) of being a dybbuk. He denies it with good-natured irony, and they begin arguing the point back and forth. Dora ends the argument by plunging an ice pick into Groshkover’s chest. He just stares wide-eyed, then continues his ironic spiel. But there is no blood. Dora takes this as proof that he really is a dybbuk. Then blood appears around the wound. But there is no anger, no sign of pain. Groshkover just says he is not feeling well, gets up, and totters off into the snowy night kvetching to himself. Velvel cries out that they are ruined. Dora just praises God and slams the door. The end.

It is bizarre and enigmatic. But one thing is clear: Reb Groshkover really is a dybbuk. Or he is something far more terrifying: a man so alienated from reality and from his own life that he can be stabbed with an ice pick and apparently feel no pain, a man whose life is ebbing away yet shows no anger or fear, a man whose relationship with reality is so mediated by words that he never stops talking long enough to confront concrete existence (like the ice pick in his chest), a man whose relationship to values is so distanced by irony that he cannot even take his own death seriously. In short, he is not a serious man. And as a rabbi, he is the embodiment of Jewish tradition.

As I see it, A Serious Man is a movie written and directed by two secular Jews in which they explore their own awakening to the fundamental inadequacy of Judaism to deal with the serious questions of serious men. And the most serious question is the problem of evil: if God is good, all-powerful, and all-knowing, then why is there evil in the world? God wants good, he can foresee evil, he can quash evil. So why is there evil? Why do bad things happen to good people? The second part of A Serious Man is a retelling of the biblical book of Job, which raises the problem of evil but gives no serious answer to it.

This movie portrays Judaism as offering no meat, no marrow, no spiritual sustenance (see also Kevin MacDonald’s review). It is just a dry bone that gets stuck in the throat, a bone that one can neither swallow nor spit out.

The main story of A Serious Man takes place in 1967 somewhere in the upper Midwest, pretty much the time and place that Joel and Ethan Coen came of age. Their equivalent in the movie is Danny Gopnik (Aaron Wolff), a 14 year old about to have his Bar Mitzvah. Danny is introduced in Hebrew school, bored out of his mind, listening to The Jefferson Airplane’s “Somebody to Love” on a radio with an earpiece. (Or is it a cassette player? The fact that somebody else later in the film listens to the same song on it leads one to think it is a tape player. But did they even exist in 1967? Is this an anachronism?).

Danny is caught by his teacher, and his device is confiscated. Unfortunately, he has hidden $20 in it to pay a fellow classmate, the bully Flagel, for marijuana. So he is in for a tense bus ride home. At home, he will listen to a Hebrew cantor on LP to prepare for his Bar Mitzvah and suffer through yet another fuzzy broadcast of F Troop because dad needs to climb up on the roof and adjust the aerial.

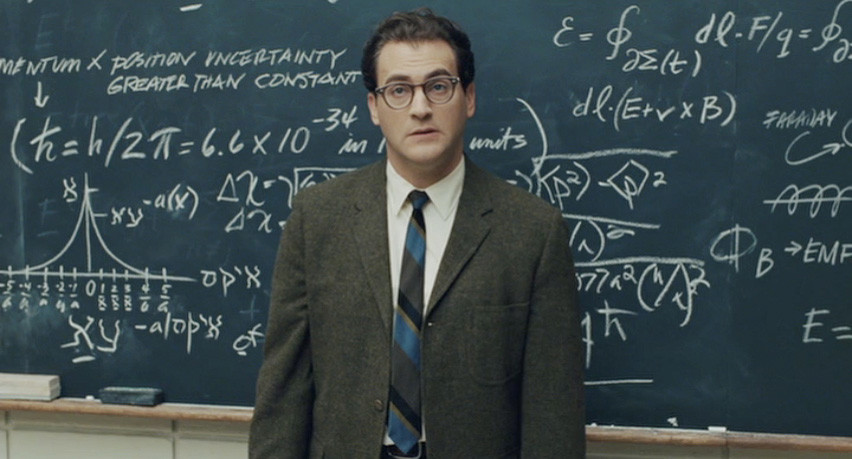

These petty concerns are introduced to contrast to the bigger problems faced by Danny’s father Larry Gopnik (Michael Stuhlbarg), who is the Job character.

Where to begin?

Larry is a physics professor at a university. He is going up for tenure. He is informed by his department chair that somebody has been writing anonymous letters to the committee accusing him of moral turpitude. But not to worry, they won’t affect the decision. When a Korean student, Clive Park, fails his midterm, he comes to Larry demanding a passing grade. He leaves behind an envelope of cash. Later in the movie, Park’s father confronts Larry and threatens to sue him for taking bribes if he does not raise his son’s grade. And he threatens to sue him for defamation if Larry tries to return the bribe. (Did we even have Koreans in 1967?) Oh, and Dick Dutton from the Columbia Record Club keeps calling Larry’s office demanding payment for his selection of the month (Santana Abraxas—not released until 1970, by the way).

After just such a typical day at work, Larry returns home to his harpy wife Judith (Sari Lennick), who tells him that she is leaving him. She wants a divorce and a gett, a Jewish ritual divorce so she can marry Sy Abelman. (The incredulous question “Sy Abelman? Sy Abelman?” is a constant refrain in this movie. The unspoken thought is: “Why would any woman want Sy Abelman?”) Sy Abelman (Fred Melamed) is a hugger and a toucher, a lumbering, soft-spoken, “sensitive” guy who uses his New Age persona as a passive-aggressive wedge to invade people’s space. Oh, and we later find out that he is the creep writing letters to Larry’s tenure committee.

Sy and Judith think it is reasonable for Larry to move out of his house into a hotel before the divorce. It is, of course, out of the question that Judith move in with Sy. Judith later empties the couple’s bank account to hire an aggressive divorce attorney. The divorce seems to be called off, however, when Sy is killed in a car accident. Judith, however, thinks it is reasonable for Larry to pay for Sy’s funeral.

Then there is Larry’s brother Arthur (Richard Kind), a brilliant but troubled loser who is staying with the family. Arthur is in constant rows with Larry’s homely daughter Sara over the use of the bathroom. (Remember when houses had just one bathroom?) Sara needs the bathroom to wash her hair. Arthur needs the bathroom to drain his facial cyst. Arthur spends his time scribbling in a notebook. He is working on “the mentaculus,” a mathematical theory to tie together all of reality and help him make money at cards. When Larry sneaks a peek, the pages are filled with gibberish. Arthur is just insane. He is picked up by the police for gambling. Later, he is arrested for soliciting sodomy, adding to Larry’s mounting legal bills.

And finally there are the goys next door: buzz-cut, blonde, blue-eyed goys, tossing baseballs around and shooting deer. The goys are encroaching on the Gopniks’ property, mowing over onto their lawn and building a boat shed (but of course) too close to the line. Larry has to shell out money to yet another lawyer to look into it. He is told that his money has been well-spent, that the lawyer stumbled across something that everybody else would have overlooked. But before he can tell Larry, he drops dead of a heart attack right in front of him. Later Larry has a nightmare that he and Arthur are being hunted by the goys like deer. Always innocent. Always persecuted. Such is the burden of being a Jew.

It is all too much. Larry needs help. A woman he knows tells him that he doesn’t have to go through it alone. He’s a Jew. Jews have this great well of tradition to draw upon. He should talk to the rabbi.

The first rabbi he sees, Scott Ginzler, is a freshly minted junior rabbi who goes by rabbi Scott. What he lacks in life experience he makes up for with enthusiastic blather. How should Larry deal with his problems? By trying to look at them in a new perspective. He should try to see the hand of God in his troubles. God is everywhere, says rabbi Scott, even in the parking lot. Of course Larry’s problem is not that he doesn’t see God’s hand. He wonders why God is giving him the finger.

Rabbi Scott was no help, so Larry goes up the hierarchy to rabbi Nachtner (George Wyner), who fobs Larry off with God’s answer to Job: “I’m the boss around here. Who are you to complain? Where were you when I created the world? I have no obligations to you. No, you can’t know why.” Nothing that a serious man can take seriously.

Then rabbi Nachtner launches into a well-rehearsed spiel about another congregant, a dentist, who finds Hebrew letters on a goy’s teeth. The letters spell out “Help me.” He is thunderstruck. Is it a message from God? He begins looking in other mouths, but nothing. He translates the letters into numbers. It looks like a phone number. He calls it. It is a grocery store. No answer there. Eventually, he comes to the rabbi Nachtner to ask him what it means. Does it mean he should help people? The rabbi has no answer for the dentist either. But helping people? Can’t hurt. Eventually, the dentist just stops thinking about the issue. Rabbi Nachtner suggests that Larry will eventually stop thinking about his problems too.

The rabbi Nachtner working a suicide hotline? Probably not a good idea.

Larry, stunned by the unhelpfulness of it all, at least wants to know “What happened to the goy?”

“Who cares?” says the rabbi.

Rabbi Nachtner’s message at Sy Abelman’s funeral is similarly unhelpful. He speaks of “olam ha ba”—the promised world to come, surely a topic of interest at a funeral. What is olam ha ba? It is not a place, like Canada, says the rabbi. It is not the land of milk and honey. It is not the heaven of the gentiles. It is the bosom of Abraham. Yes, well, but what does that mean? Does it mean the Jewish community? Well Sy has died and left that.

Nachtner’s handling of Danny Gopnik’s bar Mitzvah is similarly inept. He reels off his speech as if he has a cab waiting.

Larry does not get to see the senior rabbi, rabbi Marshak, who is reputed to be a very learned man. But he rabbi won’t see him. He is busy. He’s thinking.

Young Danny Gopnik does, however, get to see rabbi Marshak. The old tzadik always speaks a few words of wisdom to the Bar Mitzvah boy. Danny enters the rabbi’s vast office, passing from room to room past paintings, books, and artifacts that exhale an air of wisdom, arcane knowledge, and secret traditions. As the old bearded face comes into view, I was half-expecting to see the dybbuk Groshkover. But no.

Rabbi Marshak pulls out Danny’s confiscated music device and intones: “When the truth is found to be lies. And all the hope within you dies . . .” It is the Jefferson Airplane song Danny was listening to when the device was confiscated, although the rabbi has changed the word “joy” to “hope.” The words, and the fact that rabbi Marshak chooses to utter them, perfectly sums up the disillusionment with Judaism that is the theme of the whole movie.

The rabbi then reels off the names of four members of Jefferson Airplane: Marty Balin, Grace Slick, Paul Kanther, and Jorma Kaukonen. (Aside from Slick, who is descended from the Mayflower settlers, they are all Jews.)

Finally, to underscore the emptiness of it all, the rabbi returns Danny’s device and says “Be a good boy.” That’s it.

Jews cannot swallow their tradition or spit it out, so they enact it in “scare quotes,” with irony. But why does any serious man remain a Jew? Well, many Jews who are serious about intellectual or spiritual matters don’t.

And as for the ones who do, their motives are hinted at in A Serious Man. As the movie rolls on, it becomes clear that virtually everyone Larry Gopnik knows is a fellow Jew, even the people one does not initially think are Jews, for example, the first lawyer he sees, who has an office full of fishing trophies and who seems never to have heard of a gett; Larry’s department chair, who gives him tenure despite the fact he has never published (Elena Kagan is not at all unusual); even the painted, pot-smoking, two-timing Jezebel next door.

When it comes to the spiritual problems of serious men, there are better religions than Judaism. (Not that much better, really, since some questions just can’t be answered.) But when it comes to delivering the goods of community, no religion can compare. And it is the Jewish disdain for the goys so evident in this movie, as well as the Jewish dual ethical code—one standard for the Jews, another standard for the rest of us—that has sustained their community down through the millennia. That’s why the Jews are still with us and the Hittites aren’t.

There are lessons here for serious men: white men serious about our own people’s survival.

Comments are closed.