The Jewish War on White Australia: Colin Tatz and the Genocide Charge—PART FOUR

Go to Part 1.

Go to Part 2.

Go to Part 3.

The “Stolen Generations”

Colin Tatz has made the “Stolen Generations” the lynchpin of the “genocide” charge he levels against White Australia. The myth of the “Stolen Generations” was born in 1981 with the publication of a short pamphlet by a postgraduate history student, Peter Read, who argued that part-Aboriginal children were systematically removed to separate them from the rest of their race, claiming that “welfare officers, removing children solely because they were Aboriginal, intended and arranged that they should lose their Aboriginality, and that they should never return home.” He based this controversial thesis on interviews with Aborigines about their experiences with the welfare system, and his research into the New South Wales official records, from which he asserted that 5,625, or up to one in six Aboriginal children had been taken in New South Wales with the intent of permanent removal from their culture between 1883 and 1969.

Read, who wrote his pamphlet “at white heat in a single day,” initially wanted to call it “The Lost Generations” but his wife thought this too bland and suggested the more polemical “Stolen Generations.” Following its enthusiastic reception on the radical Left, Read, who later became Professor of History at the University of Sydney, hardened his thesis to claim Australian authorities sought not just to end Aboriginal culture, but to physically eliminate Aborigines altogether: “Their extinction, it seemed, would not occur naturally after all, but would have to be arranged.” In later writings, he drew an explicit analogy between the “Stolen Generations” and “the Holocaust.”[1]

Read’s thesis was the default assumption for the polemical Bringing Them Home report of 1997, the result of an inquiry by the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, which claimed that, in various parts of the country, up to one in five Aboriginal children were forcibly removed from their families during the sixty years prioe to 1970. This report relied on the anonymous and unverified testimony of people claiming to have been affected by removals. Echoing the later pamphlet by Read, a finding of genocide was presented: the removals were intended to “absorb,” “merge” and “assimilate” the children, “so that Aborigines as a distinct group would disappear.” It urged the federal government to apologize and offer compensation to the alleged victims and their families.

In 2008, then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd issued a formal apology, declaring “for the removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families, their communities, and their country. For the pain, suffering and hurt of these Stolen Generations, their descendants and for their families left behind, we say sorry.”

Two decades after the publication of Read’s pamphlet, historian Keith Windschuttle took the trouble to examine all 1,200 pages of records Read claimed to have studied, and found his research and conclusions, the two foundational props of the Stolen Generations myth, were filled with errors and distortions.[2] Tatz’s response to this devastating critique of Read’s figures and methodology is to label Windschuttle a “denier,” and insist “debates about quantification in genocide context are not a key issue. The fulcrum is intent, and the nature of the act(s) rather than raw numbers or percentages.”[3] Thus, when the alleged actions that form the basis of the “Stolen Generations” charge are shown to bogus, Tatz resorts to arguing this is ultimately irrelevant because “intent” is sufficient for the charge to be levelled: “Did such actions occur? In any discussion of genocide, the intent rather than the motive and the actual outcome is all that matters.”[4]

Tatz continues to cite Read’s pamphlet as a trusted source, and to assert that Aboriginal children were removed as part of a genocidal policy of assimilating them into the White Australian population. He also continues to recycle the totally discredited claim that 100,000 part-Aboriginal children were removed even though fellow “Stolen Generations” propagandist Robert Manne acknowledges the 100,000 number, contained in the Bringing Them Home report, is entirely spurious, the result of a journalist’s misunderstanding of an observation by Peter Read but then uncritically recycled during in the Bringing Them Home report, and repeated on many occasions since.[5]

After carefully combing through the public records, Windschuttle put the total number of Aboriginal children taken into care from 1880 to 1970 in all states and territories of Australia at 8,250. This figure includes children fostered or adopted into White families, those forcibly or voluntarily separated from their parents for good (and sometimes bad) reasons, those sent with parents’ consent to be educated and trained elsewhere, and those taken away because they were neglected or abused by their parents.[6] Windschuttle found no evidence of any policy by any state or federal government to steal children from parents to eliminate the Aboriginal race.

Despite Windschuttle’s debunking of the “Stolen Generations” myth, Tatz continues to assert that Aboriginal child removals, rather than motivated by concerns for child welfare, were prompted by White authorities responding to its “Aboriginal problem” by finding a “solution in biology” based on “the forcible removal of Aboriginal children from their parents, and their subsequent assimilation by intermarriage into white society.”[7] To support this contention, he cites a handful of statements made by White Australian clergymen and bureaucrats at various points in the twentieth century, such as a brief statement from a national summit at Canberra in 1937 that: “The destiny of the natives of Aboriginal origin, but not of full blood, lies in their ultimate absorption by the people of the Commonwealth and it is therefore recommended that all efforts shall be directed to this end.”[8]

Tatz takes for granted the desire expressed in this and similar statements (to assimilate mixed-descent Aborigines into the White Australian population) is “genocidal,” claiming that such ideas “go to the heart of genocidal thought and action, resorting to biological solutions to social and racial problems.”[9] He also regards historical laws banning Aboriginal intermarriage with Europeans as a viciously racist “intrusion into marriage and sexual relations.”[10] White Australians are thus condemned for promoting the genetic assimilation of Aborigines and for preventing it.

Despite the statements Tatz cites as evidence to support his genocide charge, there is no evidence such views ever gained wide support or were translated into government policy. Historian Bain Attwood notes how “these statements of intent” are invariably “mistaken for action(s)” by the likes of Tatz and Manne who, in their writings, seem to assume the espousers of such views “won broad acceptance for their eugenicist policies and were able to implement them,” when the reality is that “a close reading of the historical record of actions does not support this claim.”[11]

Despite their strident claims, Tatz and Manne have, as conservative journalist Andrew Bolt repeatedly points out, been unable to identify even ten children “stolen” just for being Aboriginal. The judiciary in the Northern Territory has been unable to find any evidence of a “stolen generation,” despite a huge test case and subsequent appeal. Activist lawyers picked Lorna Cubillo and Peter Gunner as their first and best two claimants from among 550 people in the Northern Territory who registered with them as having been “stolen” for being Aboriginal. The Howard government in power at the time fought the claims and won. The Federal Court in 2000 found that Gunner had been sent to Alice Springs by his mother for schooling, and Cubillo had been rescued from a bush camp where she was found abandoned by her father, her mother dead and her grandmother far away. Witnesses in the case who also signed up were all shown not to have been “stolen.”

Professor Robert Manne

After going through the records of Aboriginal policy in the Northern Territory, the judge ruled that the “evidence does not support a finding that there was any policy of removal of part-Aboriginal children such as that alleged by the applicants.” That finding was upheld on appeal and no evidence to the contrary has emerged since that finding. Court cases in Western Australia and South Australia have likewise found no proof children were “stolen” from their families just for being Aboriginal, rather than for being abandoned or abused. Those claiming to be “stolen” have, on closer checking, turned out to have been rescued instead—just as authorities still rescue Aboriginal children today.

Tatz claims in his book Australia’s Unthinkable Genocide that officials in Victoria in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries used their “powers to remove children of mixed descent, to absorb them physically and culturally and so end their Aboriginality” with between 20,000 and 35,000 children taken away “to institutions to extinguish their Aboriginality” and that this “became a cornerstone of action by state and federal administrators.”[12] He neglects to mention that the Victorian Labor government was informed by its specially appointed Stolen Generations Taskforce in 2003 that while some 36 organizations were now helping the state’s “stolen generations,” not one truly “stolen” child could be found. In fact, the Aboriginal-led taskforce admitted that in the entire history of Victoria there had been “no formal policy for removing children.”

In Western Australia, a Supreme Court judge rejected claims there was ever any official program in the state to implement a “Stolen Generations” policy of forced assimilation into the White Australian community. Justice Pritchard dismissed damages claims by the Aborigines Don and Sylvia Collard and seven of their 14 children removed or made state wards. She specifically dealt with a claim that the children were removed “pursuant to a policy of assimilation of aboriginal children,” instead finding they were removed to safeguard their physical welfare, finding “the references to ‘assimilation’ in the evidence I have set out above are not sufficient to support a finding on the balance of probabilities that at the time of the wardships there was, within the Department of Native Welfare or the Child Welfare Department, the pursuit of a policy of assimilation of aboriginal people into white Australian society through the wardship of aboriginal children.”

In truth, the so-called “Stolen Generations” saved thousands of children from systematic abuse, neglect and molestation. Figures released in 2016 by the Australian government Institute for Family Studies show that nearly 17,000 Aboriginal children are in out-of-home care, up 65 percent since former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s apology to the “Stolen Generations” in 2008. Reflecting on these figures, an incensed Greens MP recently declared: “It’s just ludicrous. Saying sorry (for the ‘Stolen Generations’), say you’re not going to do it again, and we still continue to see our children being ripped out of mothers’ arms.” The ABC interviewed a “stolen generations survivor” who likewise complained that this alleged child-stealing was still happening: “They have to stop taking our kids.” The ABC failed to explain that these children—like the “stolen generations” before them—were taken to save them from being neglected, starved, bashed or raped. Aboriginal children are today five times more likely to be hospitalized for assault and almost ten times more likely to be taken into care.

“Justification of genocidal practices”

Tatz labels any justification for the removal of Aboriginal children on welfare grounds as “lame attempts at justification of genocidal practices.” Nor, apparently, does it concern him that the “Stolen Generations” myth he so zealously propagates is killing Aboriginal children today by making authorities reluctant to save Aboriginal children from dangers that would once have prompted immediate intervention. The “Stolen Generations” myth necessitates denying that Aboriginal children are being removed today for good reasons as this implicitly concedes that the “Stolen Generations” were very likely removed for good reasons too. The results of this particularly noxious brand of anti-White activism are truly horrific for Aboriginal children today.

Earlier this year, the Northern Territory’s child protection minister refused to rule out allowing a toddler who had been raped in a suburban home in an Aboriginal community in Tennant Creek from returning to the same house where the rape had occurred. The house was in an area locals call “The Bronx,” notorious for alcohol-fueled violence. A subsequent investigation found the girl, who was infected with a sexually transmitted disease, was raped in an entirely foreseeable attack. Child protection services received 52 reports on the children in the family documenting “all possible harm types” including experiences of, and exposure to, domestic violence and parental substance abuse, truancy, neglect, emotional harm, physical harm and sexual abuse of children. Police had 150 “recorded interactions” with the child’s parents and siblings. Only after being raped was the child and her brother removed from their mother’s care by the Department of Child Protection South Australia.

In Queensland, officials took an Aboriginal girl from her White foster parents and returned her to the dysfunctional Aurukun Aboriginal community, where she was pack-raped again.

An epidemic of similar cases in Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory necessitated a direct military intervention by the Howard government over a decade ago. A long-serving pediatrician who worked in Alice Springs in the Northern Territory, Tors Clothier, notes that child abuse is rife in remote Aboriginal communities and doubts many Aboriginal females made it to puberty without experiencing unwanted sexual attention: “Abuse is rife. I thought vividly of the case of a seven-month-old child who was badly raped years ago and died from her injuries. My impression was that sexual and physical abuse of children was common.” Clothier said that during his long career he had become increasingly frustrated with the reluctance of child protection services to protect at-risk children: “Clearly with the spectre of the Stolen Generations hanging in the background, people are reluctant to take away kids. … The children that were being injured or neglected or physically abused were not at the apex of the triangle where they should have been.”

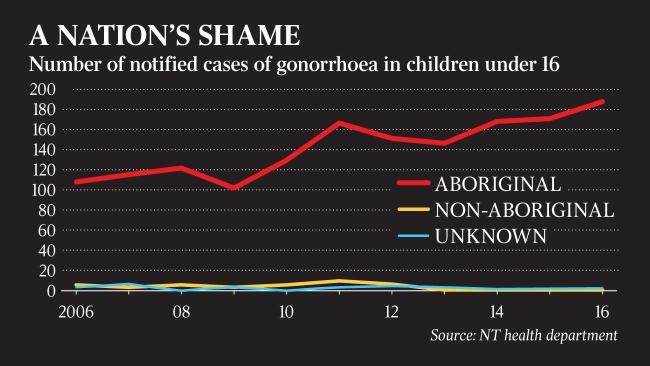

The Australian recently reported that “Child protection authorities are overwhelmed by the scale of neglect and under-reported sexual activity involving children in the Northern Territory, which has seen rates of sexually transmitted infections soar over the past decade.” In the decade between 2006 and 2016, “the numbers of notified cases of childhood STIs rose by as much as 180 percent for some diseases. Underage Aboriginal girls are now almost 60 times more likely to contract syphilis than their non-Aboriginal counterparts and 30 times more likely to contract gonorrhea or trichomoniasis, according to official figures.” These figures reveal the horrifying extent of child sexual abuse in Aboriginal communities. Aboriginal men made up two-thirds of all those charged in the Northern Territory with child sexual offences over the past ten years, despite Aboriginal people only comprising one-third of the Territory’s population.

Former Northern Territory child protection minister John Elferink has attacked agencies who, because of the “Stolen Generations” myth, are now reluctant to remove at-risk children, noting how “On one occasion I had to support my department CEO’s sacking of a manager because that manager endorsed an underage marriage rather than protect the child because the manager unilaterally decided it was culturally acceptable. Sadly, kinship care as a concept has decayed into simply making excuses for child abuse for cultural reasons. Genital mutilation is one such example.”

Tatz slams politicians and bureaucrats for banning Aboriginal rituals like circumcision and subincision [the slitting open of the male urethra] and child marriage, which he regards as unwarranted intrusions into traditional Aboriginal culture which he regards as having “world’s best practices in terms of child-rearing.”[13] Among these “world’s best practices” banned by the White authorities was the practice of the “intercision of the girls at the age of puberty. The vagina is cut with glass by the old men, and that involves a great deal of suffering.”[14]

The Australian recently observed how that “the shadow cast by the Stolen Generations has meant authorities (not only in the Territory) are extremely reluctant to remove at-risk children from their families, and preferred placement with relatives may not eliminate the risk.” Aboriginal woman Jacinta Price noted that “Many of us who have known of the sex abuse horrors for years have been trying to reveal the truth while others while others have attempted to shut us down. Claims of ‘racism’ and ‘impacts of colonisation’ have been the easy distraction from this disgraceful situation, which is all too prevalent in some Aboriginal communities.”

None of this dissuades Tatz from opposing the removal of Aboriginal children from dangerous homes. Instead he maintains that:

The paradigm of Aboriginal families as sites of danger and risk for their children continues to be rolled out to endorse ongoing removals and to raise public support for stricter levels of government intervention and management, ostensibly to improve health and wellbeing. The Federal Government used allegations that child sexual abuse was rife in Indigenous communities to validate the invasive actions of the Northern Territory Intervention. The West Australian government made similar claims in threatening to close up to 150 communities. The forced removal of Aboriginal children remains an integral process of the Australian settler colony.

This shift has been accompanied by greater prevalence of populist racist characterisations of neglect and abuse as pertaining to cultural and individual Indigenous deficits rather than founded in colonial experiences and systemic disadvantage. Fears of so-called problem populations—Indigenous, ethnic, refugees and asylum seekers—threaten national security and peace. Global terrorism generates dehumanising of “problem populations” and support for harsh solutions that hark back to carceral institutions for Indigenous populations in settler colonial states.[15]

Instead of being “founded in colonial experiences and systemic disadvantage,” the anthropological evidence shows that extreme physical and sexual abuse of women and children was a normative part of pre-contact Aboriginal culture. Historian John Kimm points out that “the sexual use of young girls by older men, indeed often much older men, was an intrinsic part of Aboriginal culture, a heritage that cannot easily be denied.”[16] Playwright and author Louis Nowra concurs: “Despite local variation, there is a consistent pattern of Aboriginal men’s treatment of women that was harsh, sexually aggressive (gang-rape for instance) and, in our term, misogynist. Given its pervasive nature across the whole of Australia, we can say that it was ancient and long-lasting.”[17]

Nowra cites an anthropologist in Queensland who described how, at the turn of the twentieth century when a girl of the Pitta-Pitta tribe first showed signs of puberty, “several men would drag her into the bush and forcibly enlarge her vaginal orifice by tearing it downwards with the first three fingers wound round and round with opossum string. Other men come forward from all directions, and the struggling victim has to submit in rotation to promiscuous coition with all the ‘bucks’ present.” Even worse was his description of practices around Glenormiston in Victoria, where: “A group of men, with cooperation from old women, ambush a young woman, and pin her so an old man can slit up the shrieking girl’s perineum with a stone knife, followed by sweeping three fingers round the inside of the vaginal orifice. She is next compelled to undergo copulation with all the bucks present; again the same night, and a third time, on the following morning.”[18]

In traditional Aboriginal culture there are no age restrictions at which a girl would be delivered up to a much older man, and it was not an “uncommon occurrence to see an individual carrying on his shoulder his little child-wife who is perhaps too tired to toddle any further.” In 1905 the local telegraph operator in Queensland reported that a five-year old half-caste girl, Polly, was taken by an Aboriginal man who, with others, raped her over two days. The operator noted that such actions “are very common among the men.”[19]

John Elferink observes that too many children were being “left in harm’s way because we have become gun-shy of trampling on culture” by removing them: “if we accept the notion that cultural practices justify the suspension of the human rights of a child then we need to be prepared to accept that we support the notion that children will be in sexual relationships.”

Conclusion

The decades-long propagation of the genocide charge against White Australians by Tony Barta, Colin Tatz and a phalanx of other Jewish academics and intellectuals is an especially pernicious example of Jewish ethnic warfare through the construction of culture—in this case Australia’s historical narrative. In levelling the “genocide” charge these ethnic activists seek to exercise the kind of psychological leverage that has been used with such devastating effect against generations of Germans and the West in general (e.g., in the UK, the legacy of slavery and colonialism; in the U.S., the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow laws). This is evident in their willingness to liken rejection of, or even ambivalence toward, their tendentious assertion that “Australia is a nation built on genocide” to “Holocaust denial.” This inculcation of guilt among White Australian for their supposed “genocide” of Aborigines is ultimately about suppressing opposition to non-White immigration and multiculturalism—policies that have the universal support of Australia’s Jewish activist organizations.

Given Tatz’s fervent support for Israel, despite that nation’s history of ethnic cleansing and harshly restrictive policies against all non-Jewish migrants and refugees, his sanctimonious words about the alleged historical sins and moral failings of White Australians are exposed for what they are: a mask for Jewish ethnic aggression against a feared and reviled outgroup. He informs his readers that if his “writing comes across as passionate, so be it,” insisting there “can be no dispassion in matters of race, let alone genocide.”[20] While blatant activism should evoke discomfort in the academy—given its incompatibility with detached reflection and scholarly objectivity and integrity, Tatz is unusually upfront about his agenda: “My bias is clear,” he affirms in Obstacle Race, his major treatise on the racism that is supposedly ubiquitous in Australian sport: “it is pro-Aboriginal in most things and anti-racist [i.e., anti-White] in all things.”[21]

Observing how ethic activism permeates Tatz’s work, Tony Barta notes how he has made “everything he wrote a political intervention. He made sport an activist concept. He made Aboriginal Affairs an activist site.”[22] One Jewish source implicitly acknowledges the truth: that Tatz is not an objective, truth-seeking academic but a shameless ethnic activist and anti-White propagandist. He “does not pretend to be detached,” and beneath the thin veneer of scholarly objectivity, “the emotion ripples.” This emotion leads him to dismiss all inconvenient facts which undermine the anti-White narrative he has assiduously constructed: the extremely low mean IQ of Australia’s Aborigines, their pre-contact history of extreme violence and sexual assault (especially against women and children), and the real reasons for Aboriginal child removals in the twentieth century. Given the suffering of Aboriginal children not removed from their families because of this activism, it’s clear that Tatz does not even have the best interests of the Aborigines at heart.

Tatz lets the truth be damned and instead propagates “noble lies” intended to make White Australian feel guilty and Aborigines feel good by blaming their endemic dysfunction on Whites. This tactic is motivated by the Marxist-Leninist principle that the end justifies the means. As the goal of overthrowing the White racial and cultural domination in Australia is held to be a moral imperative that trumps literally everything else—even the interests of many of the supposed beneficiaries of this activism—presenting blatantly false accounts as authentic history, anthropology, and sociology is held to be morally justified. Consistent with the postmodernist argument that truth is only true when it benefits non-White minority groups, false accounts are not false if they contribute to the anti-White narrative and nurture White guilt and serve Jewish interests. The history of the genocide charge against White Australia, and its increasingly pernicious cultural and political ramifications, is a salutary lesson in the dangers of ceding control of people’s historical narrative to a hostile outgroup.

[1] Keith Windschuttle, The Fabrication of Aboriginal History: The Stolen Generations (Sydney: Macleay Press, 2009), 61.

[2] Ibid., 76.

[3] Colin Tatz, Australia’s Unthinkable Genocide (Xlibris; 2017), 1916.

[4] Ibid., 1952.

[5] See Bain Attwood, “The Stolen Generations and genocide: Robert Manne’s In Denial: The Stolen Generations and the Right,” Aboriginal History, Vol. 25 (Sydney: 2001), 255-56.

[6] Windschuttle, The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, 617.

[7] Quoted in: Douglas Booth, “Colin Tatz: ‘Compelled to Repair a Flawed World,’” In: Genocide Perspectives: A Global Crime, Australian Voices, Ed. Nikki Marczak & Kirril Shields (Sydney: UTS ePress, 2017), 14.

[8] Colin Tatz, Australia’s Unthinkable Genocide, 1874.

[9] Ibid., 1880.

[10] Ibid., 1612.

[11] Attwood, “The Stolen Generations and genocide,” 169.

[12] Tatz, Australia’s Unthinkable Genocide, 1844.

[13] Ibid.,1742.

[14] Windschuttle, The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, 464.

[15] Quoted in: Anna Haebich, “Reflecting on the Bringing Them Home Report,” In: Genocide Perspectives: A Global Crime, Australian Voices, Ed. Nikki Marczak & Kirril Shields (Sydney: UTS ePress, 2017),40-41.

[16] A Fatal Conjunction: Two Laws Two Cultures (Sydney: Federation Press, 2004), 24.

[17] Nowra, Bad Dreaming: Aboriginal Men’s Violence Against Women & Children (Melbourne: Pluto Press, 2007), 24.

[18] Ibid., 16.

[19] Windschuttle, The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, 443.

[20] Tatz, Australia’s Unthinkable Genocide, 104.

[21] Colin Tatz, Obstacle Race: Aborigines in Sport (Sydney: UNSW Press, 1995), 8.

[22] Douglas Booth, “Colin Tatz: ‘Compelled to Repair a Flawed World,’” In: Genocide Perspectives: A Global Crime, Australian Voices, Ed. Nikki Marczak & Kirril Shields (Sydney: UTS ePress, 2017), 14.

Comments are closed.