“Envying the cruel falcon”: The Anti-Liberal Poetry of Robinson Jeffers, Part One of Two

Only the most ardent followers of the right wing nationalists, the lunatic fringe, and the most ardent of Roosevelt haters could, after reading The Double Axe, welcome the return of Robinson Jeffers.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 1948

In two previous essays I explored the nature of academic ethno-activism in the deconstruction of the cultural legacy of the Modernist poets Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot. Such deconstructions, which are ongoing, target the posthumous legacies of creative thinkers deemed by the current dispensation to have held quasi-Fascistic socio-political views. The essays on Eliot and Pound were intended as broad overviews of this process of deconstruction, emphasizing the scale of successive critiques and, to some extent, illuminating the psychology of those behind them. Analysis of the actual poetic content produced by those creatives was peripheral. This was partly because, although they have been subjected to withering criticism with the ultimate intention of consigning them to distant memory, neither Pound nor Eliot have yet disappeared entirely from view, and their works continue to be widely sold in bookshops, studied in colleges, and read in libraries. Thus, while Pound and Eliot are being “phased out” culturally, or held up as examples of “bigoted old White men,” the depth and intensity of their fame have meant that they continue to put up a spirited resistance to being forgotten.

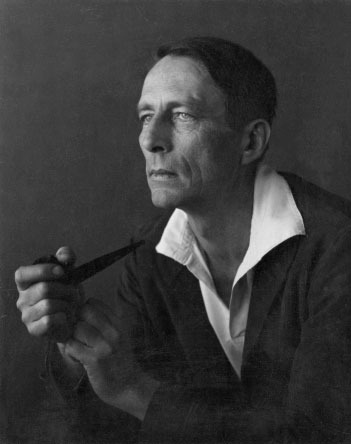

Robinson Jeffers (1887–1962), the subject of this essay, has found this task much more difficult. Despite once adorning the cover of TIME magazine (April 4, 1932), Jeffers’s fall from grace began earlier, and has been more complete. Studied only rarely in colleges and almost entirely exiled from bookshops and popular discussion, Jeffers and his poetry are a niche literary interest at best. Even within our circles, aside from a single lecture by Jonathan Bowden (which takes the form of a brief cultural biography and glosses over the content of Jeffers’s poetry), he remains largely ignored or unknown. In part to rectify this, the focus of the present essay will be mainly on the poet’s biography and content, with the deconstructive element relegated to the background.

There are a number of reasons for Jeffers’s descent from the heights of popularity, and these reasons make both the man and his work an interesting study. Within a decade of his appearance on the front cover of TIME, Jeffers found himself pilloried as an isolationist opposed to American involvement in World War II, and even as a “fascist sympathizer” who produced “unpatriotic verse.” Jeffers had attracted increasing interest, and then suspicion, from liberals who reacted with horror to his scathing rebukes of, and deep pessimism towards, their schemes for “human improvement.” A close inspection of the reclusive Jeffers’s works revealed a man railing against the decadence of the inter-war period. Piercing that maelstrom of cultural degeneration, his poetry was a furious cry against cherished concepts like “equality,” “progressivism,” and “social justice.” In Jeffers’s unflinching vision, God and Nature were intertwined, inseparable. Man was “nature dreaming,” and the further Man distanced himself from Nature, natural instinct, and natural law, the further Man descended into weakness and decay. Violence, of a noble, natural kind, is glorified in Jeffers’s poetry, as is normal, healthy, and natural sexuality. Read more

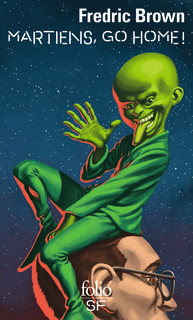

Many a science fiction book or film has a theme, or a debate therein, dealing with the question of whether “aliens” who are advanced enough to master space travel would, ipso facto, “come in peace.”

Many a science fiction book or film has a theme, or a debate therein, dealing with the question of whether “aliens” who are advanced enough to master space travel would, ipso facto, “come in peace.”