Ancient Resistance in Red, Black and White: The “Anti-Semitism” of Grimm’s Fairy Tales

Fairy tales, for me, have always evoked powerful feelings of the mysterious and mist-shrouded history of European peoples. Both before and after coming to White racial consciousness, there was always something “enchanting,” to use a word, about the tales and their faraway castles, strange creatures and ever-present dark woods. Like a non-Jewish version of the Old Testament, they were filled with sex, violence and the occasional morality lesson.

Also like the Old Testament, there’s a noticeable “flatness” to the fairy tales. There is no drama or character development to speak of, just matter-of-fact recitations of what happens next. Uncensored, politically incorrect — folklore in the raw. Given that, I had to wonder how, exactly, the Jews of old Europe would have been considered at the time these tales were being passed around.

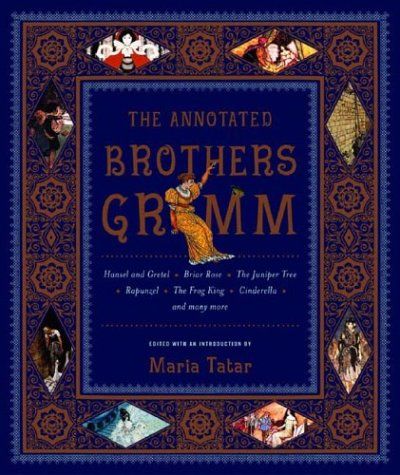

The Annotated Brothers Grimm, a Christmas present to my children, lets us know.

The book, published in 2004 and annotated by Harvard scholar Maria Tatar, presents the tales in their originally published form in 1857. It’s got well-known tales like Rapunzel, Cinderella and Little Red Riding Hood, as well as more obscure ones.

In the back, there is an “adult” section that includes a heretofore censored tale, “The Jew in the Brambles.” In the tale, a Jewish merchant is forced to dance by a magic violin while stuck in a thicket of painful brambles. Safe to say, Jews are not presented sympathetically in the tale. The player of the magic violin, an honest servant who got the violin from a gnome, tells the Jew, “You’ve skinned people plenty of times. Now the brambles can give you a scraping.” Only when the Jews offers his sack of coins does the torture stop.

From there, the Jew is portrayed as mouthy, a tattletale (he complains about the torture to the local judge). Ultimately, he is hanged as a thief for having stolen the coins himself in the first place. (Loud but hypocritical complaints about injustice and running to the authorities for punishment of enemies do seem to be Jewish attributes that continue to this day.) Tatar tells us that “anti-Semitism in its most virulent form” (why do they always use that term, “virulent”?) was found in two tales of the Grimm’s original compact edition, “The Jew in the Brambles” and “The Good Bargain”. Left out was “The Bright Sun Will Bring It to Light”, a tale Tatar describes as illustrating the compulsion to confess by a young man who murders a Jew. Only “The Jew in the Brambles” appears in Tatar’s volume.

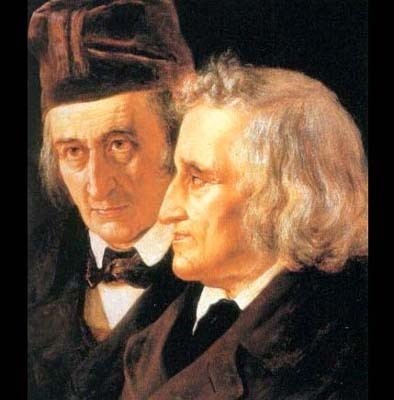

In the introduction by A.S. Byatt, we learn that the British occupying forces in Germany after World War II banned Grimm’s Fairy Tales because “they fed a supposedly bloodthirsty German imagination.” And indeed, the Grimm brothers (Jacob and Wilhelm) did have nationalistic aims, Byatt says. They believed they were “recovering a German mythology and a German attitude to life. They saw themselves as asserting what was German against the French occupying forces of the Napoleonic Empire.”

One scholar quoted mentions that while French tales were “realistic, earthy, bawdy and comical, the German (tales) veer off toward the supernatural, the poetic, the exotic, and the violent.”

How violent? In the original Cinderella (so named because she slept in the cinders), the wicked stepsisters are forced by the stepmother to actually cut off parts of their feet in order to fit in into the slipper. The blood dripping from the slipper gives them away. This is in contrast to the sanitized version I grew up, where the stepsisters merely tried to force their feet into the slipper.

The tales are loaded with “cruelty, violence, and atrocity, fear of and hatred for the outsider, and virulent anti-Semitism”, said L.L. Snyder, in “Cultural Nationalism: The Grimm Brothers’ Fairy Tales.” And yes, we actually hear that the “ashes of Cinderella were a precursor to the ashes of Auschwitz.” (The same point is made in the New York Times review by Neil Gaiman: ”The Jew in the Brambles” casts a long shadow back through the book, leaving one wondering whether the ashes Cinderella slept in would one day become the ashes of Auschwitz.) But keep in mind, Byatt says, that life in those days was already pretty cruel and violent.

An introductory piece says that the National Socialists endorsed Grimm’s Fairy Tales as a Haubuch, or “domestic manual for instilling in children a sense of racial pride. For many Nazi commentators, the protagonists of the tales offered models of ‘folkish virtues’, for these characters followed their racial instincts and demonstrated courage in the struggle to find a racially pure marriage partner.”

Another scholar cited by Byatt points out that “folktales have certain colors — red, White, black, and the metallic colors of gold and silver and steel.” More National Socialism, I suppose.

So what are racially conscious Whites to make of all this? For one, it’s hardly unique for Germanic peoples to have concocted violent tales that instill a fear of outsiders, including Jews. This is perfectly in line with the evolutionary development of any group that survived the ages. Jews, of course, have the Old Testament, where brutality toward outsiders guided by a spiritual command is pretty much the theme of the whole thing. Is there a difference?

Beyond that, I recommend Grimm’s Fairy Tales for your children. You can enjoy them on their “traditional” terms, i.e., beloved tales with helpful moral threads, or on a racial-national defense level. Or both. It’s yet another way that choosing to live White carries multiple benefits — good for us now, good for us later.

In a biographical sketch of Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm contained in the volume, they are portrayed as poverty-stricken but driven collectors of a culture: in addition to the tales, they began work on the German Dictionary and pretty much laid the foundation for the study of Germanic culture. They seemed to have a sense that this culture was under attack, and sought to preserve it the best way they knew how. It’s safe to say they had success.

Comments are closed.