Gasbags Are Not Great: Christopher Hitchens as Crypto-Rabbi

Georgians and Genomes

The independent socialist George Orwell (1903–1950) was, it’s said, a central influence on the neo-conservative Christopher Hitchens (1949–2012). But this claim puzzles me. I’ve been reading Orwell all my life and I’ve failed to notice that he was a tedious, self-righteous, self-important gasbag who never used one word when six not unpolysyllabic lexical items might, perchance, be of utility instead. See? Puzzling. Maybe I’m not reading Orwell right. All the same, Orwell can certainly shed light on Hitchens’ psychology. Like his fellow atheist Richard Dawkins, Hitch was a devout believer in the Miracle of Human Equality: he was sure that there is only one brain, the Human Brain, and that all human groups have an equal share in it. Bearing that in mind, please examine this passage from God Is Not Great (2007), Hitch’s best-selling diatribe against religion:

In 2005, a team of researchers at the University of Chicago conducted serious work on two genes, known as microcephalin and ASPM, that when disabled are the cause of microcephaly. Babies born with this condition have a shrunken cerebral cortex, quite probably an occasional reminder of the period when the human brain was very much smaller than it is now. The evolution of humans has been generally thought to have completed itself about fifty to sixty thousand years ago (an instant in evolutionary time), yet those two genes have apparently been evolving faster in the past thirty-seven thousand years, raising the possibility that the human brain is a work in progress. In March 2006, further work at the same university revealed that there are some seven hundred regions of the human genome where genes have been reshaped by natural selection within the past five thousand to fifteen thousand years. These genes include some of those responsible for our “senses of taste and smell, digestion, bone structure, skin color and brain function.” (One of the great emancipating results of genomics is to show that all “racial” and color differences are recent, superficial, and misleading.) (Op. cit., ch. 6, “Arguments from Design,” pg. 34)

George Orwell

Thus Hitchens reveals himself as opposed only to some religions, quite at home with another. To a believer in brain-equality, everything leading up to the final parenthesis is heretical in tendency, because it suggests that separate human populations can quickly evolve differences in “brain function.” In other words, different races can have different psychologies and different levels of intelligence. Realizing the ideological danger, Hitchens resorts to piety and reminds himself and his readers of PC dogma: Race Does Not Exist (amen). Orwell satirized this slavish adherence to ideology in Nineteen Eighty-Four (1948):

Crimestop means the faculty of stopping short, as though by instinct, at the threshold of any dangerous thought. It includes the power of not grasping analogies, of failing to perceive logical errors, of misunderstanding the simplest arguments if they are inimical to Ingsoc [the ideology of government], and of being bored or repelled by any train of thought which is capable of leading in a heretical direction. Crimestop, in short, means protective stupidity. (Op. cit., Part Two, chapter 9)

I’ve read all of Orwell’s books several times and hope to do so again. I find it difficult to read anything by Hitchens even once. Orwell was a good writer and an honest man who was not inspired by vanity and hatred. Hitchens was a bad writer and a dishonest man who was definitely inspired by vanity and hatred. This is why I am puzzled by the claims that Orwell influenced Hitchens. I can’t see it myself.

Karl and Kołakowski

On the other hand, I can see very clearly that Hitchens was influenced by two other famous socialists: Karl Marx and Leon Trotsky. Throughout his adult life, Hitchens believed in using violence to create a better world. Violence in word and deed is central to Marxism, as the anarchist Mikhail Bakunin (1814–76) pointed out in the nineteenth century. In his magisterial Main Currents of Marxism (1978), the Polish philosopher Leszek Kołakowski describes Bakunin’s critique like this:

Bakunin … not only combated Marx’s political programme but, as he often wrote, regarded Marx as a disloyal, revengeful man, obsessed with power and determined to impose his own despotic authority on the whole revolutionary movement. Marx, he said, had all the merits and defects of the Jewish character; he was highly intelligent and deeply read, but an inveterate doctrinaire and fantastically vain, an intriguer and morbidly envious of all who … cut a more important figure than himself in public life. (pg. 248) Bakunin … inveighed against universities as the abodes of elitism and seminaries of a privileged caste; he also warned that Marxist socialism would lead to a tyranny of intellectuals that would be worse than any yet known to man. (Op. cit., Vol. I, The Founders, Clarendon Press, Oxford, pg. 250)

Bakunin’s warning was abundantly proved in the twentieth century, when despotic, vengeful, fantastically vain intriguers like Lenin, Trotsky and Stalin came to power in the Soviet Union. After Lenin’s death in 1924, Trotsky was outmanoeuvred by his rival Stalin, forced into exile, and finally assassinated in Mexico by a Stalinist agent in 1940.

Prattle and Battle

However, if Trotsky had won the battle for power, there is no reason to believe that he would have behaved less murderously and given less licence to his followers than Stalin did. He might easily have been worse. Here are Trotsky’s views on the role of violence in politics:

As for us, we were never concerned with the Kantian-priestly and vegetarian-Quaker prattle about the “sacredness of human life.” We were revolutionaries in opposition, and have remained revolutionaries in power. To make the individual sacred we must destroy the social order that crucifies him. And this problem can be solved only by blood and iron. (Leon Trotsky, Terrorism and Communism, 4, Terrorism)

Trotsky’s words are a good guide to what he did with power himself. They are also a good guide to what his modern followers would do with it should they ever win it. In fact, the violent and vengeful neo-conservatives are among those followers: their faith in “Bombs and Bullets for a Better World” can easily be traced to Trotskyist roots.

That is why Christopher Hitchens found it so easy to become a neo-conservative. As a student, he had been part of a Trotskyist sect called the International Socialists, or I.S., the predecessor of Britain’s modern Socialist Workers Party, or S.W.P. In his autobiography Hitch-22: A Memoir (2010), Hitchens lists Rosa Luxemburg and Leon Trotsky as two of his “favorite characters in history” (“Something of Myself,” pg. 333). Here he is describing his time as a disciple of Trotsky:

The “I.S.,” as our group was known, had a relaxed and humorous internal life and also a quizzical and critical attitude to the “Sixties” mindset. We didn’t grow our hair too long, because we wanted to mingle with the workers on the factory gate and on the housing estates. We didn’t “do” drugs, which we regarded as a pathetic, weak-minded escapism almost as contemptible as religion (as well as a bad habit which could expose us to a “plant” by the police). Rock and roll and sex were OK. Looking back, I still think we picked the right options. (Op. cit., Atlantic Books, 2010, “The Sixties: Revolution in the Revolution,” pg. 88-9)

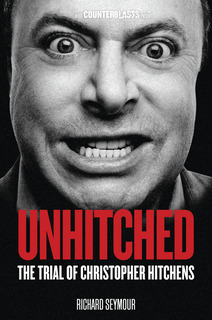

There is, I hope to demonstrate, a lot of unconscious irony in that passage: the “contemptibility” of religion, for example, and the “pathetic, weak-minded escapism” of drugs. But let’s start with something more fundamental: Hitchens’ biology. The Trotskyist gasbag Richard Seymour, a journalist, theoretician and committed anti-racist, has recently commented on the features of Christopher Hitchens by placing an example of them on the cover of his polemic Unhitched: The Trial of Christopher Hitchens (2013).

Hitchens looks not merely unhitched, but unhinged. And he doesn’t look very English. That is, I suggest, a clue to his biology and the psychology it produced.

Another clue is found in his liking for alcohol and tobacco. He gave up smoking towards the end of his life, but his “Short Footnote on the Grape and the Grain” in Hitch-22 was always true:

Alcohol makes other people less tedious, and food less bland, and can help provide what the Greeks called entheos, or the slight buzz of inspiration while reading or writing. The only worthwhile miracle in the New Testament – the transmutation of water into wine during the wedding at Canae – is a tribute to the persistence of Hellenism in an otherwise austere Judaism. (Op. cit., “Something of Myself,” pg. 351)

I suggest that Hitchens sought the same thing in politics as he did in alcohol: a buzz, a heightened sense of reality and purpose. Often it was a buzz of violence and self-righteousness:

Did I go to a vast demonstration in Grosvenor Square in London, outside the American embassy, which turned into a pitched battle between ourselves and the mounted police, and wonder in advance how many people might actually be killed in such a confrontation? Yes I did, and I can still recall the way in which my throat and heart seemed to swell as the police were temporarily driven back, and the advancing allies of the Vietnamese began to sing “We Shall Overcome.” I added to my police record for arrests, of all of which I am still reasonably proud … When found guilty, my comrades and I rose to our feet in the dock and sang “The Internationale,” fists raised in the approved and defiant manner. (“Chris or Christopher?”, pg. 108-9)

Thug is a Drug

Hitchens abandoned thuggish Trotskyism as a route to righteous thrills, but he continued to seek them in other ways to the end of his life: in thuggish neo-conservatism, for example. But then neo-conservatism is a mutant form of Trotskyism, so that isn’t surprising. Hitchens also sought a buzz from militant atheism. In God Is Not Great, he writes of the “servile absurdity” of monarchism, the “vile system of apartheid in South Africa” and of how “the Church of Rome” is “befouled by its complicity with the unpardonable sin of child rape.” That is self-righteous, moralizing language and “sin” is a religious concept. But Hitchens didn’t let logic or a sense of the absurd get between him and the buzz he obtained from the release of certain chemicals in his brain.

There are many more examples of self-righteousness in his memoir Hitch-22. For example, he talks of “the treasonous pro-apartheid riff-raff around Ian Smith,” the Rhodesian prime-minister who resisted the authority of the British government during a Black insurgency (pg. 177). In other words, Smith was disobeying a government that Hitchens himself wanted not merely to disobey but to overthrow by force.

Ian Smith and his riff-raff also foresaw what would happen in Rhodesia under Black control. Hitchens did not. After all, Smith was a vile racist, Hitchens a religiously devout egalitarian. Here he is again on his Trotskyist days at Oxford:

I can’t be as proud now as I was then of also hosting Nathan Shamurira, a spokesman for the black majority in white Rhodesia, for whom we arranged a meeting in the precincts of Rhodes House itself, one of the great imperialist’s many endowments to Oxford. He spoke persuasively enough, but the next time I saw him in the flesh he was a minister in Robert Mugabe’s unspeakable government. (“Chris or Christopher?,” pg. 100)

Note that Hitchens was only less “proud now” than he was “then” of helping that “unspeakable” government into power. Fortunately, “in compensation,” he could then say that he was as proud as ever of helping make Nelson Mandela, then a prisoner on Robben Island, “an honorary vice president of the Labour Club” at Oxford. The Western media do not like to publicize the consequences of toppling White racism in South Africa, but Mandela’s African National Congress will one day demonstrate certain biological realities even better than Mugabe’s ZANU-PF (Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front). The civilizations created by one human group are not faring well under the control of another human group. This is puzzling, if you believe that there is only one race, the human race.

Reading, Writing Rabbi

Hitchens fervently believed in One Human Race, but his own biology contradicted him: he belonged to a distinct group of human beings. I’ve already noted his love of alcohol. Here he is explaining how it did not affect his literary output:

On average I produce at least a thousand words of printable copy every day, and sometimes more. I have never missed a deadline. I give a class or lecture or seminar perhaps four times a month and have never been late for an engagement or shown up worse for wear. (“Something of Myself,” pg. 350)

This is another important part of the biology of Christopher Hitchens: he was able to absorb and produce words at high speed over many decades. What he absorbed from others was often very good: the words of George Orwell and Evelyn Waugh, for example. What he produced for himself was, in my opinion, often very bad. He was a turgid writer whose work is full of bombast and pomposity. This is from his introduction to an edition of George Orwell’s Diaries:

It may not be too much to claim that by undertaking these investigations Orwell helped found what we now know as “cultural studies” and “post-colonial studies.” His study of unemployment and housing for the poor in the North of England stands comparison, with its careful statistics, with Friedrich Engels’s Condition of the Working Class in England, published a generation or two earlier. But with its additional information and commentary about the reading and recreational habits of the workers, the attitudes of the men to their wives, and the mixtures of expectation and aspiration that lent nuance and distinction to the undifferentiated concept of “the proletariat,” we can see the accumulation of debt that later “social” authors and analysts owed to Orwell when they began their own labors in the postwar period. … Orwell illustrates the potential power of the working class to generate its own resources out of an everyday struggle, but also to generalize that quotidian battle for the resolution of greater and nobler matters, such as the ownership of production and the right to labor’s full share. (The Importance of Being Orwell, Vanity Fair, August 2012)

Note how “everyday struggle” becomes “quotidian battle.” That was how Hitchens kept up his word-count: by ignoring Orwell’s essay “Politics and the English Language” (1946) and constantly breaking rules like these:

(ii) Never use a long word where a short one will do.

(iii) If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out. (Op. cit.)

I would suggest that Hitchens’ facility with words was an example of the Three R’s: he was a reading, writing rabbi, rather like the late (and definitely great) Larry Auster. But Auster was a much better writer and a much cleverer man than Hitchens. He was also much less successful and famous, because, unlike Hitchens, he did not attach himself to the thuggish cult of neo-conservatism. However, Auster and Hitchens owed their intelligence and verbal skill to the same genetics. Immediately after disclosing “Something of Myself” in Hitch-22, Hitchens begins “Thinking Thrice about the Jewish Question…”:

In what was once German Prussia, in the district of Posen and very near the border of Poland, there was a town called Kempen which had, for much of its existence, a Jewish majority … A certain Mr Nathaniel Blumenthal, born in Kempen in 1844, decided to leave or was possibly taken by his parents, but at all events arrived in the English Midlands and, though he married “out,” became the father of thirteen Orthodox children. … In 1893, one of old Nate’s daughters married a certain Lionel Levin, of Liverpool … My mother’s mother, whose birth name was Dorothy Levin, was born three years later, in 1896. (pg. 354)

Hitchens did not know about this ancestry while he was growing up, but after he discovered it his grandmother “seemed determined to play the part of a soap-opera Jewish granny … ‘I could always see it in you and your brother: you both had the Jewish brains’” (pg. 355).

Heresy and Hair-splitting

The brother, Peter Hitchens, is another writer and broadcaster. A much better one, I would say, and his brains haven’t led him to a life-long hatred of religion – or rather, of Christianity. Here is Christopher Hitchens in Chapter eight of God Is Not Great, which describes how “The ‘New’ Testament Exceeds the Evil of the ‘Old’ One”:

The truth is that the Jews used to claim credit for the Crucifixion. [The Jewish philosopher] Maimonides described the punishment of the detestable Nazarene heretic as one of the greatest achievements of the Jewish elders, insisted that the name Jesus never be mentioned except when accompanied by a curse, and announced that his punishment was to be boiled in excrement for all eternity. What a good Catholic Maimonides would have made! (pg. 39)

That is a good example of how Hitchens’ bigotry against Christianity corrupted his thinking. Yes, Maimonides might indeed have made a good hate-filled Catholic. But that is evading the obvious fact that he was already a good hate-filled Jew. Hitchens himself was aware of his anti-Christian, pro-Jewish bias and discussed it in Hitch-22:

As a good atheist, I ought to agree with Voltaire that Judaism is not just one more religion, but in its way the root of religious evil. Without the stern, joyless rabbis and their 613 dour prohibitions, we might have avoided the whole nightmare of the Old Testament, and the brutal, cruel wrenching of that into prophecy-derived Christianity, and the later plagiarism and mutation of Judaism and Christianity into the various rival forms of Islam. Much of the time, I do concur with Voltaire, but not without acknowledging that Judaism is dialectical. [E]ven pre-enlightenment Judaism forces its adherents to study and think, it reluctantly teaches them what others think, and it may even teach them how to think also. … Much of my Marxist and post-Marxist life has been spent in apparent hair-splitting and logic-chopping, and I still feel that the sheer exercise can command respect. It may even build muscle. (“Thinking Thrice about the Jewish Question…” pg. 376)

But what about the even later “plagiarism and mutation of Judaism and Christianity” into “the various rival forms” of Marxism? Hitchens acknowledges the religious nature of his old opinions in God Is Not Great:

Rosa Luxemburg seemed almost like a combination of Cassandra and Jeremiah when she thundered about the consequences of the First World War, and the great three-volume biography of Leon Trotsky by Isaac Deutscher was actually entitled The Prophet (in his three stages of being armed, unarmed, and outcast). As a young man Deutscher had been trained for the rabbinate, and would have made a brilliant Talmudist — as would Trotsky. (Chapter Ten, “The Tawdriness of the Miraculous and the Decline of Hell,” pg. 53)

Top of the Trots

This crypto-rabbinic reading of Marxism can be extended backwards, to Marx and Lenin themselves, and forward, to Yigael Gluckstein, the man who, under the name Tony Cliff, led the International Socialists to which both Hitchens brothers belonged at Oxford. Here is the Irish blog Splintered Sunrise discussing the unforgettable T.C., the Top Cat of Brit-Trot:

One thing that was immediately apparent about Cliff, lifelong atheist and anti-Zionist though he was, was how profoundly Jewish he was. You got this from the very cadences of his speech. There was a broad streak of the Borscht Belt comedian in there (if I heard the joke about the rabbi and the goat once, I heard it a dozen times); one could also, if one closed one’s eyes, imagine Cliff bearded and wearing a shtrayml, in the role of a Hasidic rebbe expounding his mystical interpretation of the Toyre to his fanatical band of followers. But it’s a broader cultural thing. If I say Cliff was a Talmudist, I don’t mean that as an insult. You all know, of course, that the Talmud is a codification of halokhe, of Jewish religious law, but that’s far from all it is. The Talmud is also five thousand or so pages of rabbinic sages scoring off each other using not only halokhic erudition, but also puns, insults, bad jokes, gossip and anecdotes of dubious relevance. Sound familiar? Put Cliff two millennia in the past and have him speaking Aramaic, and he’d have fit right in. (“The most unforgettable person I’ve ever met in my life,” Splintered Sunrise, August 28, 2011)

Yigael Gluckstein aka Tony Cliff

If you read the full article, you will see that it offers an affectionate, admiring portrait of someone who would, if he’d achieved the power he sought, have replaced Britain’s liberal democracy with a brutal dictatorship. But a menu of torture, murder and concentration camps seems to lose its unpleasant flavour when the chef is on the left.

Tony Cliff’s former disciple Hitchens wrote in God Is Not Great of “days when I miss my old convictions as if they were an amputated limb” (ch. 10, pg. 53). And, as noted above, Trotsky remained one of Hitchens’ “favorite characters in history.” But Hitchens was happy to report that, despite abandoning overt Trotskyism, he felt “no less radical” (ibid.). His politics still gave him a buzz, in other words, and satisfied his crypto-rabbinic urge towards absorbing and producing vast quantities of words at high speed.

Men of Steel

In other individuals, this crypto-rabbinic urge has produced other things, as Hitchens, to his credit, acknowledges in Hitch-22:

And thus to my final and melancholy point: a great number of Stalin’s enforcers and henchmen in Eastern Europe were Jews. And not just a great number, but a great proportion. The proportion was especially high in the secret police and “security” departments, where no doubt revenge played its part, as did the ideological attachment to Communism that was so strong among internationally minded Jews at that period: Jews like David Szmulevski [author of Resistance in the Auschwitz-Birkenau Camp]. There were reasonably strong indigenous Communist forces in Czechoslovakia and East Germany, but in Hungary and Poland the Communists were a small minority and knew it, were dependent on the Red Army and aware of the fact, and were disproportionately Jewish and widely detested for that reason. Many of the penal labor camps constructed by the Nazis were later used as holding pens for German deportees by the Communists, and some of those who ran these grim places were Jewish. (“Thinking Thrice About the Jewish Question…,” pg. 372–3)

“Grim” is perhaps not the mot juste. But Hitchens would not have accepted any role for biology in the conflicts he discusses: as I pointed out above, he was a neuro-miraculist who believed in one race, the human race, and in one brain, the human brain. Stephen Jay Gould, another great crypto-rabbi of neo-Marxism, worked for decades to promote and spread the idea that all human groups are equal in intellect and psychology. Hitchens refers to Gould several times in God Is Not Great and salutes him as a “great paleontologist” (ch. 6). But I would suggest that Hitchens, Gould, Gluckstein et al. were ethnically motivated in their opposition to biological determinism. As reading, writing rabbis, they are good examples of the Three R’s that have exercised so much influence on the modern West. What Hitchens calls the “intellectual and philosophical and ethical glories” of Marxism are crypto-rabbinic, not secularist or atheist.

So are the authoritarianism and violence of Marxism. It is dangerous to investigate and discuss certain topics in a Marxist state, whether it is openly Marxist, like the old Soviet Union, or implicitly so, like the modern West. Free speech has steadily diminished in all Western nations: in Europe, Canada and Australia you go to jail for heresy, in the United States you lose your job and reputation. The First Amendment is still in force in the United States, but American progressives want to sweep it away as a relic of the unenlightened racist past. In the meantime, they do their best to make free speech as costly as possible for people who exercise it in heretical ways. We can see the consequences of this enforced closure of debate in such insanities as mass immigration and egalitarianism.

By recklessly opening their borders and relentlessly pursuing equality, Western nations are inviting reality to punish them hard. Reality will not fail to oblige. And we will have crypto-rabbis like Christopher Hitchens to thank for it.

Comments are closed.