Christianity and Sociobiology

Human Sin or Social Sin: Evolutionary Psychology, Plato and the Christian Logic of Sociology

Paul Dachslager

Charleston, SC: CreateSpace, 2016

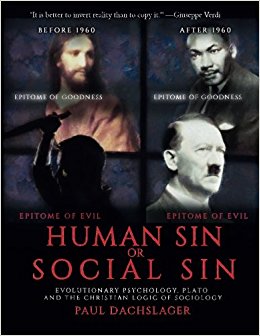

The title of a book often best indicates the author’s approach to his subject matter. For that matter, the somewhat lengthy subtitle of Paul Dachslager’s book could be replaced by a more explicit inscription of his, such as “On the White Man’s Mimicry of the Other,” or “The Inversion of the Truth,” or “The Power of Changing Paradigms.” The author’s main thesis is that with dominant political ideas always subject to change, the reader’s conceptual tools are also bound to undergo change. What many evolutionary psychologists in their research on race took for granted fifty or sixty years ago must, as a result of the pressure of new political myths, be now either discarded, or short of that, wrapped up in a more hermetic language designed for the eyes and ears of the initiated only. With the pervasive secular religion of political correctness reigning now supreme in US academia and the mainstream media, even the strongest empirical evidence on the disparities of IQs among races, the role of hereditary genius, and genetic influences on criminality must be carefully reworded in a more arcane language.

As Paul Dachslager correctly observes at the outset of his book, in our hyper-moralistic and hyper-altruistic world, scholarly incursions into the role of biological influences in explaining human behavior are met with social opprobrium and are often dubbed with a derogatory label of “scientism.” Once upon a time Whites had to expunge their bodily sins by abiding with the carnality-hating canons of the Church; today Whites have to expunge their social sins by demolishing traditional racial thinking. “As the body was once stigmatized or banned, today the social body [i.e., race, class, and gender] should be banned.” In both cases we can observe the state of self-denial of penitent Whites, reflecting itself on the one hand in the excessive display of false piety towards the Other, and in a subconscious search for the retrieval of their lost racial and ethical grandeur, on the other.

This can best be seen in contemporary Whites’ self-inflicted mimicry of African American social comportment, which by definition demands self-abasement for Whites. This is a classic example of an inverted form of racism, which always provides a good conscience. The politics of guilt, or the politics of mimicked atonement, or the politics of false penitence, or, better yet, collective self-hate, have become by now a standard ritual of academics and politicians in the European Union and United States. The merit of the author is that with his interdisciplinary approach his analyses touch on a wide range of fields, thus making his book an easy read for students in different areas of the social sciences. Of special interest is the author’s description of the link between Christianity and the genealogy of White penitence, a factor often neglected by many sociobiologists, who all too often focus on statistical measurements of cognitive skills of different races while neglecting the power of sentiments, the importance of political myths, and the role of religious beliefs that shape the behavior of different races and peoples. Such a reductionist approach is less pronounced in Europe than in the United States, a country where the powerful heritage of the biblical narrative, with its contemporary legal modalities, often leads to grotesque hyper-moralism among American decision makers and pathological proclivity to self-hate among ordinary Whites.

The book is composed of seventeen chapters with clear-cut themes, although each chapter, with its own central thesis and impressive bibliography, could be read as a separate essay. The author must be commended for his analytical approach to the subject matter, although, toward the end of the book one notices a didactic tone of his prose, which may be therapeutic to many self-hating Whites.

Comments are closed.