Thoughts on “Decolonization” as an Anti-White Discourse

Take up the White Man’s burden

And reap his old reward,

The blame of those ye better,

The hate of those ye guard

Rudyard Kipling, The White Man’s Burden

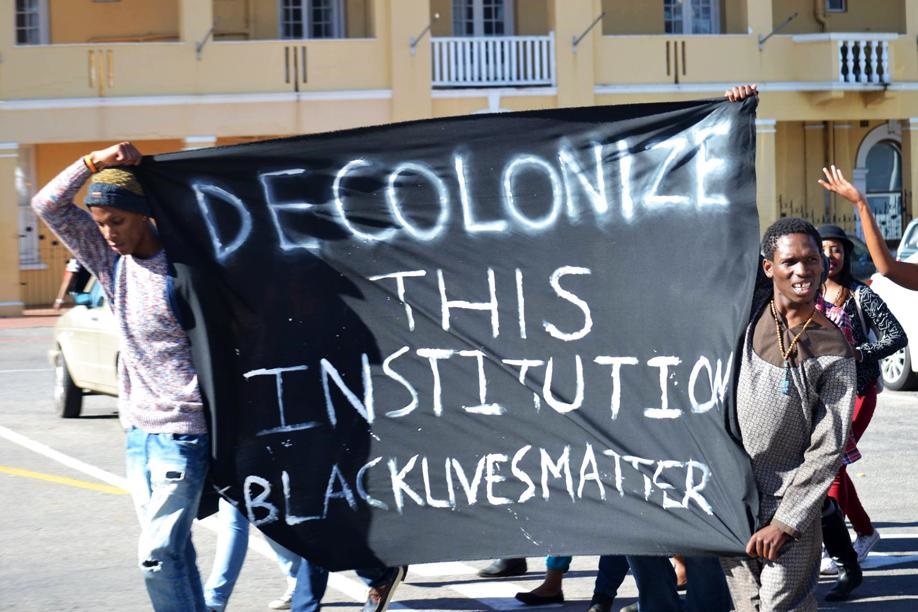

Along with ‘Whiteness Studies’ and ‘Black Lives Matter,’ the concept of ‘decolonization’ is currently rampant in Western institutions of higher education. In the most recent example, academics at England’s University of Cambridge are considering how to implement a call from a small group of Black and leftist undergraduates to “decolonize” its English literature syllabus by taking in more Black and ethnic minority writers and bringing ‘post-colonial thought’ (a branch of critical theory) to its existing curriculum. Seen in the context of similar agitation at Yale last year, ongoing “Rhodes Must Fall” agitation in South Africa, the removal of portraits of White founders from King’s College London, and attacks on statues of prominent White historical figures in the United States, the ‘decolonization’ effort is clearly part of an escalating craze for removing White presence and reducing White space throughout the West. This reduction of White space is occurring in demographic, cultural, and even historical areas; the latter involving a ludicrous ‘Blackwashing’ of periods of European history which were overwhelmingly monocultural, with gross exaggerations of non-White presence in places like Roman Britain.

Today, White nations are being demonstrably colonized by non-Whites, White culture is increasingly marginalized (or dismissed as non-existent), and White history is being rewritten to support and advance the agenda of contemporary multiculturalism. Whites are thus abused as colonizers while simultaneously being subjected to an unprecedented and multifaceted colonization. This jarring incongruence between rhetoric and reality requires an interrogation of what is meant by terms like “colonize,” “empire,” and even “genocide,” particularly in regard to the political uses they have come to acquire, and also an interrogation of what we understand by historical processes of colonization. It is argued here that the growing clamor for ‘decolonization,’ like Whiteness studies, exists only to encourage and facilitate an aggressive anti-White discourse.

Several years ago I had the opportunity to attend a conference on ‘genocide studies,’ during which I was introduced to the work of the leading academic in this field, the Australian scholar A. Dirk Moses. Despite his last name (which apparently is also English and Welsh as well as Jewish), Moses evidences no discernible Jewish ancestry, his father John Moses being a notable Anglican priest and his mother Ingrid a full-blooded German from Lower Saxony. Moses has built his career around broad explorations of the themes of colonialism and genocide, and the relationship between the two. Although he wasn’t present at this particular conference, I was very much interested in those presentations concerning his work, which I have since come to regard as being generally of a very high quality and, most importantly, wide-ranging and devoid of the mawkish (not to mention mendacious) moralism that often saturates Jewish academic treatments of these themes. To my mind Moses remains one of the most essential writers on colonialism, conquest and genocide as perennial features of the human existence, and I would have a difficult time engaging in discussion on these subjects with someone unfamiliar with his work. Importantly, Moses argues that terms like “colonization” have fluid rather than fixed definitions, especially in their discursive usage, and stresses that the meaning of such terms as “colonization” and “imperialism” have rather been adapted in recent decades in order to facilitate a political agenda — to condemn European nations and to question Western moral legitimacy.

For example, in his introduction to Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation, and Subaltern Resistance in World History (2008), Moses contends that conquest and occupation are human universals rather than the preserve of uniquely evil European peoples and their culture. He writes that “‘Empire,’ ‘colony,’ and ‘genocide’ are keywords particularly laden with controversial connotations,” but that “few are the societies that were not once part of empires, whether its core or periphery. Few are the societies that were not the product of a colonization process, whether haphazard or planned.”[1] Despite the universal presence of conquest, displacement, and domination in human history, Moses notes that the usage of the terminology of these themes has come to focus inordinately on the recent European past:

‘Empire’ and ‘colony’ are viewed through exclusively nineteenth- and twentieth-century lenses and have become words of implicit opprobrium because they connote European domination of the non-European world. … ‘Imperialism’ was coined in the middle of the nineteenth century to criticize ambitions for domination and expansion. A century later, to accuse a country of colonialism was to condemn it for enslaving and exploiting another.[2]

When utilizing these keywords then, modern ethnic activists strategically take the European expansionism of the nineteenth century as their starting point, excluding many prior centuries during which non-White participation in conquest, slavery, expansion, and imperialism was at least equally in evidence. Colonialism has thus ceased to be regarded in modern social and academic discourse as a human universal, easily explained by evolutionary impulses, and has instead come to be regarded as a dynamic in which uniquely exploitative Whites disturb the putatively utopian existence of non-Whites (a myth bolstered and promoted by Boasian anthropology), before subjecting them to unimaginably horrific treatment. Because of the lop-sided nature of contemporary discourse on colonialism and empire, Moses notes that nothing less than “the moral legitimacy of Western civilization is at stake” when defining and utilizing these keywords.[3]

One of the most interesting, and frustrating, aspects of this questioning of Western moral legitimacy is that Whites have allowed themselves to be subjected to it, sometimes even encouraging it. On some levels it would be comforting to attribute this self-flagellation exclusively to very recent alien influences, but the truth is more complex. Europeans may have had unprecedented success in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in expanding their spheres of material interest and cultural influence, but they also engaged in an unprecedented level of self-critique because of it. Moses suggests that White participation or co-operation in the questioning of the moral legitimacy of Western civilization is in part a “culmination of a long tradition of European legal and political critique of colonization and empire. … European theologians, philosophers and lawyers have been debating the morality of occupation since the Spanish conquest of the Americas in the sixteenth century.”[4]

This “long tradition of European legal and political critique of colonization and empire” could be read as evidence in support of Kevin MacDonald’s theory of ‘pathological altruism’ in European society, or the idea that Europeans have uniquely constructed their societies to place extreme emphasis on moral conformity and the rights of the individual. Whites (and the legitimacy of their civilization) are thus especially vulnerable in modern discussions of colonization, slavery, and empire, not because their actions in these areas were particularly nefarious, but because they are the only successful ethnic group in these spheres willing to subject itself to such a critique, not only by others within the ethnic group, but also by ethnic outsiders claiming moral superiority. Perhaps best encapsulated in Kipling’s poem “The White Man’s Burden“(1899), written in response to the Philippine-American War, the European experience of expansion and empire has always been double-sided, combining a love of exploration and glory with uneasy introspection prompted, as Kipling put it, by “the judgment of your peers.” It is particularly telling that in the course of hundreds of conversations with figures at all levels of the Alt Right (according to all media hype, a bastion of aggressive ethnic chauvinism), I have yet to come across a single individual advocating an expansionist or colonial policy — the preferred option being a total segregation from non-Whites and a policy of non-interference in their affairs.

Of course, one of the main reasons for our contemporary aversion to colonialism is that the collapse of empire has been catastrophic for us as a people — not in terms of lost resources, but because we immediately became subject to reverse colonization. Although accelerated by hostile alien influences, it remains indisputable that Europeans conducted their empires, particularly in their latter bureaucratic stages, in accordance with the principle that the colonized acquired a status nominally indistinct from each other as well as the conquering national/ethnic group. As Enoch Powell expressed it in relation to the British empire:

From the middle of the eighteenth century onwards, notwithstanding the loss of the American colonies, there occurred a striking expansion outside the United Kingdom of the dominions of the Crown, until those born within a quarter of the land surface of the globe were born within the allegiance, and were subsequently British subjects undistinguishable from one another in the law of the United Kingdom.[5]

In Britain, this led to an initial mass influx of non-Whites from the colonies between the passage of the British Nationality Act (1948), which defined British citizenship in accordance with the principle outlined by Powell, and the Commonwealth Immigration Act (1962), which only moderately slowed the tide. An almost identical scenario played out in France between 1945 and 1974, and in the Netherlands, which took in, between 1945 and 1990, around 730,000 migrants from the former Dutch colonies of Indonesia, Surinam, and the Dutch Antilles. It should be stated that the principles outlined by Powell were almost certainly always intended to remain just that — principles, but the vulnerability was nonetheless made available for exploitation in the form of mass non-White adoption of European citizenships. A similar vulnerability of principle may be observed in the jus soli interpretation of citizenship employed by the United States, which has been equally subjected to countless exploitations.

Another reason why even ethnocentric Whites have developed a strong aversion to colonial ambitions is that our culture has intensively absorbed and internalized the anti-imperialism of leftist intellectuals like Sartre and Fanon, for whom all empires (excluding of course the Communist ones) entailed the exploitation and degradation of indigenous peoples. Even those of us who may not necessarily believe this to be the case, and in fact see many positives for indigenous peoples in their subjugation to European rule, fail to confidently articulate such a position because of the overwhelming social and cultural success of the leftist argument. This is despite often incongruous pockets of support for European imperialism, notably that of Raphael Lemkin, the Jewish coiner of the term ‘genocide,’ who asserted that empire enabled the diffusion of culture, enabling weaker societies “to adopt the institutions of more efficient ones or become absorbed by them because they better fulfil basic needs.”[6]

Scholarly titles offering a full-blooded apologetic for European imperialism, such as The Triumph of the West (1985) by J.M. Roberts, would struggle to get published in today’s academic climate, but Roberts’s honest comments on the dualistic nature of European colonialism, and ultimate rejection of perpetual guilt, bear repeating:

If we wish to reassure ourselves about our own moral sensibility, we need only to recognize that the bearers of western civilisation have often behaved with deliberate cruelty and ruthlessness towards other peoples, that some of them plundered their victims of wealth and their environment of resources, and that still others, even when more scrupulous or well-meaning, casually released shattering side-effects on societies and cultures they neither understood nor tried to understand. For centuries, many Europeans and many European peoples outside Europe showed astonishing cultural arrogance towards the rest of humanity. In doing so, they behaved much as men of power have always behaved in any vigorous civilization. What was different was just that they had so much more power than any earlier conquerors, and even more convincing grounds for feeling they were entitled to use it. All that said, if we are seriously concerned about our own sensitivity to ethical nuance, we ought also to recognize that administrators, missionaries, teachers were often right in thinking that they brought valuable gifts to non-Europeans. Those gifts included gentler standards of behavior towards the weak, the ideal of a more objective justice, the intellectual rigor of science, its fruits in better health and technology, and many other good things.[7]

It goes without saying that the “good things” mentioned by Roberts are excluded entirely from current discussions of colonialism, which forfeit honest confrontation with the past in favor of pursuing the promotion of ‘White guilt,’ excusing the failures of predominantly African populations (non-African former colonies like Singapore appear to have succeeded greatly both during and after their experience of European empire), and facilitating ethnic revenge. These ambitions have of course been nurtured in the West’s non-White populations for some time by the same cliques in academia, the media, and the wider culture. In just one particularly egregious example, in The Strange Death of Europe: Immigration, Identity, Islam Douglas Murray cites the Jewish academic, novelist, and journalist Will Self as telling one television audience that British identity was nothing more than “going overseas and subjugating black and brown people and taking their stuff and the fruits of their labours. That was a core part of the British identity, was the British Empire.”[8]

There is of course a substantial overlap not only in the self-comforting content of Jewish and African revenge fantasies, but also in their narrative structure. Just as narratives of Jewish victimhood rely on strict definitions of anti-Semitism (perpetrated by irrational Whites against innocent Jews), and a cropped timeline of events (often starting ‘spontaneously’ in 1933, Tsarist Russia, or the Crusades), the colonial grievance industry relies on strict definitions of colonialism (perpetrated by Whites and universally exploitative and abusive) and a cropped history of imperialism that begins only with the European age of expansion. The similarity may be regarded as due to the fact that Jews have been dominant in the production of ‘White guilt’ academic literature on empire and slavery (an excellent example being Peter Kolchin’s American Slavery, 1619–1877), as well as popular cultural products of the same timbre (e.g. Steven Spielberg’s Amistad). Also, just as Jews are often portrayed as uniquely innocent, Blacks are today said to be incapable of ‘racism.’

Such simplified narratives of both colonialism and anti-Semitism imply that Blacks and Jews are incapable of ambition, greed, cruelty or hostility toward outgroups — an intellectual position worthy of ridicule were it not for the fact it enjoys substantial, if logically inexplicable, status and influence in modern culture and academia.

Equally understated in contemporary discussions of colonial scenarios is the role of native elites, an area that I am particularly interested in. I’ve long regarded the Jewish presence in Europe and European societies as a unique form of colonialism (though without the “good things” mentioned by Roberts), and this presence has been demonstrably reliant from its very early beginnings on co-operation with native European elites, as well as being very tenuous during times of political instability. Similarly, A. Dirk Moses warns against the adoption of narratives of colonialism which “regard the encounter between European and Indigene as grossly asymmetric, thereby playing down both indigenous agency and the often-tenuous European grip on power, particularly in the early stages of colonization. In German Southwest Africa, for instance, the German governor was initially reliant on local chiefs.”[9] Moses has stated elsewhere that Germans during the Weimar Republic “regarded themselves as an indigenous people who were being slowly colonized by foreigners, namely Jews.”[10] Even Raphael Lemkin himself once stated that colonialism involved a situation whereby the subjugated group was “a majority controlled by a powerful minority,” perhaps missing entirely the profundity of such a statement when applied to the activities of his own people.[11] The power of the minority often intermingled with the power of self-interested native elites. Thus, just as European understandings of the Jewish Question would be woefully incomplete without a confrontation of the issue of venal and treasonous European elites, so the attempts by post-colonial ethnic groups to place exclusive blame for their grievances on Europeans are equally inadequate.

Similarities between the European experience under Jewish influence, and the African experience under European empire are of course limited. As stated above, European influence in Africa was a net benefit, bringing manifold cultural, social, and technological benefits to African societies. No similar claim could be made about Jewish influence at any point in European history. Nor should Europeans get into the contemporary African habit of engaging in a morality-based ‘blame game’ as a means of trying to ‘decolonize’ our own nations — either of Jewish influence, or the presence of millions of newcomers from all corners of the earth. Unlike Africans, our people are remarkably successful, often against all odds and despite the negative machinations of outsiders and the corruption of their own elites. If we accept Moses’s assertion that colonization and imperialism represent a kind of pinnacle in the universal human participation in competition, then we should be wary of imbuing that competition with too much redundant moralism.

The avoidance of moralism is perhaps even more necessary for a people such as ourselves, for whom moral concerns are primary; a kind of racial Achilles heel. Simply put, we are unlikely to find success in wielding a weapon to which we are uniquely vulnerable. Our struggle against invaders, both old and new, should be based on the obvious truth that it is quite simply in our interests to defend the homogenous nature of our territory as a means of promoting a safe and successful future for our children. This is where our ‘moral’ code should begin and end.

Finally, it is worth remarking upon the rhetorical bankruptcy and transparent agenda of slogans calling for the ‘decolonization’ of academia, English literature, and our public spaces. Decolonization, by almost any definition, implies that a ‘thing’ existed in some state prior to colonization. Looked at bluntly, a complete decolonization of African society would entail a total return to the pre-imperial state of the African tribes, stripped of the positive cultural ‘diffusions’ described by Lemkin, affirmed by Moses, and praised by Roberts. There is almost certainly not a single African alive today, either in Africa or living among other peoples, who would willingly engage in such a total ‘decolonization.’ For one thing, it would imply an enormous loss in population given that the recent dramatic upsurge in African population has been fueled by Western technology and medicine.

Applied within White societies or to academic subjects of White origin such as English literature, ‘decolonization’ is technically impossible, at least from the Black perspective, because both the prior and existing state of the ‘thing’ is White, technologically and culturally advanced, etc. What Blacks truly mean, whether they understand the dialectical tricks devised by those inciting them or not, is that they want a colonization. They want to colonize White nations, White spaces, White literature with a Black or multi-ethnic presence that was never there at any prior time. Efforts to invent or exaggerate, for example, a sub-Saharan presence in Roman Britain are intended to construct a mythical multicultural ‘prior state’ that ‘decolonization’ will return us to. But these are malicious fictions. The discourse of ‘decolonization’ is simply a mask for the ongoing colonization of the West.

[1] A.D. Moses (ed), Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation, and Subaltern Resistance in World History (New York: Berghahn, 2008), p.3.

[2] Ibid, p.4.

[3] Ibid, p.5.

[4] Ibid, p.9.

[5] Quoted in M. Cross and M. Keith (eds), Racism, the City and the State (London: Routledge, 1993), p.181.

[6] Moses (ed), Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation, and Subaltern Resistance in World History, p.11.

[7] J.M. Roberts, The Triumph of the West (London: Guild Publishing, 1985), p.430.

[8] D. Murray, The Strange Death of Europe: Immigration, Identity, Islam (London: Bloomsbury, 2017), p.33.

[9] Moses (ed), Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation, and Subaltern Resistance in World History, p.16.

[10] A. D. Moses, ‘Colonialism,’ in P. Hayes & J.K. Roth, The Oxford Handbook of Holocaust Studies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), p.72.

[11] Ibid, p.9.

Comments are closed.