A Forgotten Revolutionary: John Jacobs, Founder of Weatherman

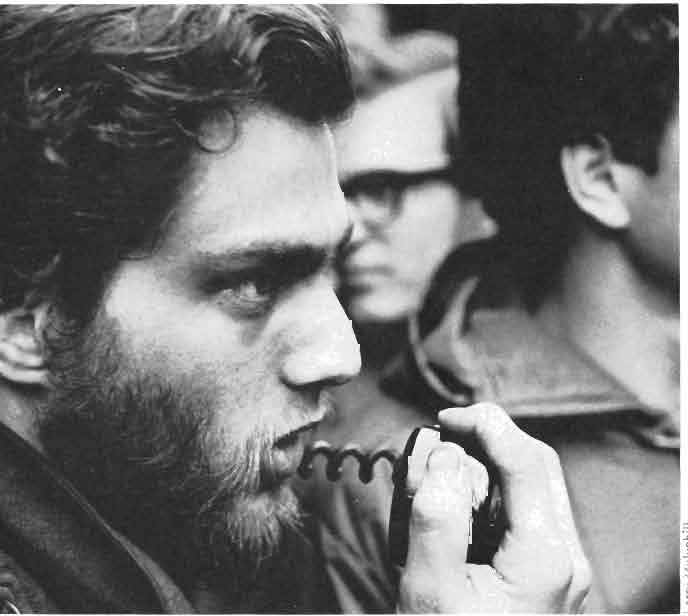

John Jacobs. From Columbia College Today, “Six Weeks That Shook Morningside: A Special Report.” Spring 1968, p. 31

Introduction

John Jacobs was the founding father of Weatherman, the late 1960s ultra-radical spinoff from Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). While Weatherman has enjoyed remarkably positive coverage in recent years, Jacobs has been virtually forgotten. One reason for that is that his rivals in the organization have been able to shape present-day perceptions of Weatherman; another is that he vanished after his expulsion from the group, relatively early in Weather’s history, never to reappear. His life is an interesting case study in Jewish revolutionary activism. (For a complementary view of Weatherman, see my previous article on Ted Gold.)

John Jacobs represents a vicious but relatively minor Jewish assault against Whites. This attack erupted out of the larger American Jewish body, at a time when the Jewish group as a whole was oriented in the same direction as Weatherman, but working with nonviolent means. The Jews in America had worked long and patiently to increase their power and to delegitimize American society in moral terms, but were not working to launch a direct attack.

Then a small group of youthful Jews formed Weatherman. At their head was John Jacobs, who led them in a frenzied attack on Whites. Although this first, premature, terroristic offensive came to a dead end, Weatherman foreshadowed a potentially far greater Jewish assault on White America.

Early Life

John Jacobs, often called “JJ,” was born in September 1947, one of two sons born to wealthy leftist Jews. His father, a former journalist, sent him to prep school in Vermont. There, Jacobs read deeply on the Russian Revolution, Marx, and Lenin in his spare time. He also became captivated by the revolutionary of the hour, Che Guevara. Jacobs’ interest in this area reveals a strong alienation from mainstream American culture — an entirely mainstream orientation among American Jews. The sources on Jacobs are sparse, but it is virtually certain he gained this cast of mind from his parents and perhaps other relatives, not from feelings of any real inequity in American society, especially since he came from an affluent background. Unlike many other 1960s radicals, he was a revolutionary from the beginning, not a reformer. In the fall of 1965 he entered Columbia University.[1]

Character of John Gregory Jacobs

Many who knew Jacobs describe him as brilliant. Mark Rudd, a fellow radical and prime source on Jacobs, said he “had brains, vision, and the ability to talk. When he was on, he was brilliant. Nobody else even came close.”[2] Rudd must be referring to tactical discussions, for Jacobs’ ideology sounds like simple Marxist boilerplate, if the following portrait is any indication:

[He was] an animated madman. He talked in breathless whole paragraphs about Lenin and Mao and Marx in [a] nasal “dese” and “dose” accent. . . . In high-volume monologues that often shifted to yelling, JJ would hold forth while guzzling a beer and smoking a skinny joint. “In order to abolish colonialism and imperialism, we need to abolish capitalism, the root cause of war, domination, class and race exploitation. When that happens, we can substitute a humane, rational economic system, socialism. The majority of the people of the world will benefit, war will be eradicated, and history can then begin, as Marx himself said somewhere. An end to exploitation! Human beings will be liberated. . . . for the first time in human history. What a wonderful era we’re in!”[3]

Jacobs affected a distinct style:

Tall and rangy, with hooded good looks and an intentionally menacing manner, Jacobs showed up for meetings . . . sporting a leather jacket and Levi’s, his shirt collar open to show a lion’s tooth on a gold chain, and his hair slicked back. . . . His style was street-corner stud . . . .[4]

Weatherwoman Susan Stern wrote that he was “pugnacious, arrogant, sneering.” Yet she also thought he was more sincere and “human” than the other Weatherman leaders.[5] Another writer claims Jacobs was “revered for his uninhibited frenzy in sexual encounters as well as in street fights with police,” that he “pushed through police lines at antiwar protests like an authentic street tough.”[6] A recent historian says some people “thought him a prophet, some a poseur, but either way he was surely the purest voice of the apocalyptic revolutionary.”[7] Jacobs would thus appear to be a good example of psychological intensity as a background trait for Jewish activism (see here, p. 24ff).

Columbia University

At Columbia, Jacobs circulated in the SDS crowd, but preserved his political independence. That fall Mark Rudd also entered Columbia; he was not a Red-Diaper Baby, so Jacobs introduced him to Marxist theory and the history of Jewish political activism.[8] Jacobs and Rudd would go on to lead the radical student takeover of Columbia in the spring of 1968.

Jews absolutely dominated Columbia SDS. Early leaders included John Fuerst, Michael Neumann, Harvey Bloom, Michael Klare, Howard Machtinger, and David Gilbert — all Jews. Mark Rudd remembers that these young men “passionately” discussed world events and they “all agreed on one solution, Marxist revolution.” Jacobs fit right in with this viewpoint, but unlike some of the others, he added a fiery commitment to revolutionary violence.[9]

In the course of 1967–68, the Columbia SDS chapter became more forceful, staging various protests over University ties with the CIA and the armed forces. However, the main thrust of the chapter leadership was organizing and educating to bolster membership. Pushing for direct confrontation with the authorities, Jacobs and Rudd formed a group called the “Action Faction.” They believed that provocative action would win converts far more quickly than simple organizing. Soon they seized upon two pretexts for an uprising.[10] Jewish SDS members (Bob Feldman among others) had discovered that Columbia was secretly doing research for the Pentagon (as part of the Institute for Defense Analyses or IDA). Columbia was also building a new gymnasium near Harlem, which gave the Action Faction an excuse to cry “racism.” Their immediate aim was to polarize the student body and radicalize as many as possible. Rudd later gloated, “We wanted to build the movement, and we succeeded.”[11]

In mid-March 1968, Rudd won election as chairman of Columbia SDS. The Action Faction was in. They were emboldened by portentous developments that suggested a nationwide or even worldwide crisis: massive inner-city riots, the rise of the Black Panthers, antiwar demonstrations that began to feature physical confrontations with the authorities, the first radical bombings, and the supposed defeat of the U.S. Army by the Vietnamese in the Tet Offensive. Many believed revolution was plausible, even imminent. Jacobs in particular insisted that events were combining to make the U.S. political system vulnerable.

On March 27 Rudd and Jacobs led a noisy demonstration into Low Library to protest IDA, and Columbia subsequently placed six of the ringleaders, including Rudd and Jacobs, on probation (the others were Ed Hyman, Morris Grossner, Nick Freudenberg, and Ted Gold). In response, Rudd and SDS called a new demonstration for April 23, which led to the invasion and occupation of several university buildings. There followed a weeklong standoff with university officials, with a substantial number of (often Jewish) faculty sympathizing with the rebellious students. Mark Rudd instantly became a media celebrity, but “insiders knew it was . . . John Jacobs who was the crucial figure behind events.”[12] Jacobs constantly pushed for greater radicalism, and spearheaded the invasion of two of the buildings, including the first overtly violent act—smashing a big plate-glass window to allow access to Low Library and the office of President Grayson Kirk (where a certain David Shapiro was photographed sitting behind the desk, smoking one of Kirk’s cigars, a nice piece of Jewish triumphalism).

Jacobs spent the next week in “liberated” Mathematics Hall, which the student occupiers christened the “Math Commune,” and which others called the “Hall of Crazies.” Radicals flocked in to revel in this new “community,” including Abbie Hoffmann of the Yippies, Tom Hayden, and the Motherfuckers from the Lower East Side. A red flag appeared on the roof, and barricades at the entrances. One witness stated that Jacobs “has completely flipped out and wants to blow up America.”[13] This is a pretty good approximation of what a political innocent would think of Jacobs’ ideas.

It took a week for the university administration to decide to call in the police, who cleared the buildings efficiently, and not much more bloodily than clever SDS provocations demanded.[14] They arrested over 700 students and outsiders. The police bust—earnestly desired by the revolutionaries as a means of polarizing the campus—earned a great deal of sympathy and support for SDS. The campus was indeed polarized. Jacobs in good Marxist fashion called it “maximizing the contradictions.”[15]

Three weeks later the radicals seized Hamilton Hall again, in response to, well, who cares? The administration quickly called the police this time, but not before Jacobs told Rudd, “I want to set a fire upstairs. These motherfuckers have got to fall.” Rudd agreed.[16] Jacobs targeted the office of a professor who had criticized the radicals, and burned his research of ten years on seventeenth-century France. The radicals denied setting the fire, which shows that it was not a “revolutionary” action, but simply an atrocious and petty act. Only decades later did Rudd reveal the fact that Jacobs was responsible.

The Columbia organizing would lead to the formation of Weatherman. Jacobs and Rudd “emerged as stars in the SDS firmament.”[17] Jacobs linked up with a rising force in the radical movement, Bernardine Dohrn. The Action Faction felt confirmed in their belief that violent action could spark polarization and engender mass support. In Ann Arbor a similar group, led by Bill Ayers, Terry Robbins and Jim Mellen, took over the University of Michigan SDS chapter. The two groups would later make up the majority of the Weatherman leadership.

Bernardine Dohrn and Jacobs

Bernardine Dohrn, the new ally and lover of Jacobs, was a twenty-six-year-old, half-Jewish radical with a law degree. She was “brilliant, cool, focused, militant, and highly sexual.”[18] She had thrown herself into the antiwar movement and hit New York in the fall of 1967 in a miniskirt and high leather boots. In June 1968 she won election as one of three SDS national officers; during the election a suspicious member asked her, “Do you consider yourself a socialist?” She “eyed him evenly for a moment and then answered: “I consider myself a revolutionary communist.” She won in a landslide.”[19] Well, well, well: two Jewish communists suddenly spring up like dragon’s teeth out of the foam of the New Left. Together she and Jacobs began planning to take over SDS and lead a revolution.

Jacobs, Dohrn, and a few friends began to formulate ideas. They based themselves in the Chicago apartment of Jacobs and Dohrn, near the National Office of SDS. They hosted movement heavies, consumed acid and speed in raucous parties, and listened to Jacobs spout his revolutionary theories, which met with general acceptance. Dorhn’s family had not been political and she now got a “crash course” in anti-imperialist ideology from Jacobs.[20]

Weatherman Ideology

By the spring of 1969, Jacobs was hard at work on a manifesto, which was eventually entitled “You Don’t Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows” (by Terry Robbins, from a Bob Dylan song: Jews all around). He was only twenty-one years old, and his ideology was half-baked at best. He drafted it with input from an informal committee, but it seems he did virtually all the writing. The committee, which represented the nascent leadership of Weatherman, consisted of five Jews (Jacobs, Dohrn, Rudd, Machtinger, Terry Robbins) and six non-Jews (Jim Mellen, Gerry Long, Bill Ayers, Karen Ashley, Jeff Jones, and Steve Tappis).[21] Ideologically, Mellen and Long were easily the most important gentiles. Yet, they and two more of the non-Jews soon opted out of Weatherman, leaving only Jones and Ayers. The Jews all remained true believers.

The manifesto was meant to distinguish them from the opposing faction in SDS, Progressive Labor (PL), a hardline Marxist party, a breakaway from the U.S. Communist Party (led by Milt Rosen), that strove to shape SDS policy. Perhaps the main point of difference between them was that PL did not support the struggle of the Black Panthers because they considered them “nationalist” and thus outside the all-important Marxist framework of class. The Weathermen would have to defeat PL if they were to control SDS.

Jacobs’ paper was a call for violent revolution: the “goal is the destruction of US imperialism and the achievement of a classless world: world communism.”[22] Imperialism and racism—the most important pillars of “white power” in the minds of these Jews—were the two biggest bogeymen slated for destruction.

Jacobs’ main ideas are as follows:

- The main struggle in the world was that between America and Third World independence struggles (there was no reckoning with the Soviet bloc or the imperatives of the Cold War).

- The American imperialist system with its natural expansionist dynamic would become over-extended and ripe for a fall (Marxist dogma).

- The Black struggle was the most important revolutionary struggle inside America, and the Whites’ primary duty was to support the Blacks (the Weather leaders admired the Black Panthers passionately, a feeling which was not reciprocated).

- The adult White working class was happy with the benefits derived from imperialism, and was not suitable revolutionary material. They were racists enjoying their White privilege — an early harbinger of the rejection of the White working class by the mainstream left that is such a prominent feature of American politics today.

- Weatherman thus had to mobilize the working-class youth and the hippies (of which Weatherman had little understanding or sympathy).

- Armed struggle was necessary; incidents of “exemplary violence” would win converts and forge a revolutionary army. Reform efforts were rejected as simply tending to expand what they implicitly conceptualized as White privilege.[23]

Had this program succeeded, needless to say, the lives of Whites in America would have become nasty, brutish, and short. A small clique of fanatical anti-White Jews and philo-Semites would have had the fate of millions of Whites in their hands. Quite clearly, this program of anti-White hatred has made considerable progress in the 50 years since the origins of Weatherman; indeed, it is entirely mainstream on the left in contemporary America.

Jacobs’ paper, and Weatherman’s subsequent course of action, actually had the effect of cutting Weatherman off from the larger antiwar movement, including SDS. Few were prepared to follow them in making actual war on the U.S. government. However, the wider radical movement did not disagree with their ultimate aims, but only their tactic — an important point.

The Birth of Weatherman

The showdown with PL occurred at the June 1969 SDS National Convention in Chicago. After raucous debates, Bernardine Dohrn made a long speech reading PL out of the organization: “SDS can no longer live with people who are objectively racist, anticommunist, and reactionary. Progressive Labor Party members . . . and all others who do not accept our principles … are no longer members of SDS.”[24] The Weathermen marched out, fists raised, yelling “Power to the People.”

John Jacobs, who liked to operate behind the scenes, had no recorded role in these events; neither did he become one of the elected officers of the “new” SDS. However, he and Dohrn dominated the informal (and real) leadership group that began calling itself the “Weather Bureau.” His agenda was still their guiding template. First item of business: preparation of a “National Action” for Chicago that fall. This was intended as a full-scale attack on the city and its police force: the inaugural battle of the Weatherman “revolutionary army.”

They had no real plan at all, however, other than “tear the fucker down, smash the State!” (I often need to remind myself that these were just kids in their early twenties). The first evening they shivered in Lincoln Park, depressed that only five or six hundred people showed up. They nevertheless ran out of the park smashing windows and attacking police — not unlike the actions of contemporary antifa. The riot lasted less than an hour, terminating with efficient police work and seventy arrests. The leaders were quickly bailed out, but the Weathermen were traumatized at their obvious, humiliating failure. They cancelled much of their remaining schedule. (One day it rained, allowing the Chicago Sun Times to report, “The revolution was cancelled on account of rain.”) Jacobs did not participate the first night, holding himself in reserve for later events.

The Weathermen held another march a few days later. This time Jacobs rallied the troops. He could not help tying their action to the fight against Germany in World War II — a frequent theme with the Weathermen; Rudd would later say, “World War II and the holocaust were our fixed reference points”[25] — a good indication of their strong Jewish identification. “There is a war in Vietnam and we are a Vietnam within America . . . We are going to change this country. . . . The battle of Vietnam is one battle in the world revolution. It is the Stalingrad of American imperialism. We are part of that Stalingrad.”[26]

The resulting riot was even more violent than the first, but ended in like manner. Jacobs was in the front line, fought with the police, and was arrested.

Jacobs at the National Action (center) (http://jewishcurrents.org/october-8-days-of-rage/)

Weatherman spun the defeat as a victory. They boasted they had set a precedent of revolutionary violence in America, and established themselves as a serious force in the minds of the authorities. Both true, but only at some cost. Yet they did shift their strategy. Jacobs “urged the other Weatherman members . . . to take the movement underground. His argument won the day.”[27] Under Jacobs’ guidance they switched from open provocations to clandestine terror.

Soon after, four people took charge of Weatherman: Dohrn, Jacobs, Terry Robbins, and Jeff Jones. Genetically, two and a half Jews out of four; over sixty percent Jewish leadership of the only Communist group in America committed to revolutionary violence.[28] And this we are not supposed to notice. (Incidentally, Dohrn was in the process of moving on from Jacobs to Jeff Jones.)

Flint War Council

Weatherman’s new guerrilla strategy was meant “to force the disintegration of American society via a bombing campaign to create chaos.”[29] To prepare, they would hold a final national meeting in Flint, Michigan. There, general craziness combined with serious political discussions. One writer aptly called it the “pep rally from hell.”[30] A string of Weather leaders made inflammatory speeches between group discussions.

First Dohrn boasted of her and Jacobs’ revolutionary style, saying, “We were in an airplane, and we went up and down the aisle ‘borrowing’ food from people’s plates. They didn’t know we were Weathermen: they just knew we were crazy. That’s what we’re about, being crazy motherfuckers and scaring the shit out of honky America.”

Jacobs followed her speech with his latest contribution to revolutionary theory: “We’re against everything that’s ‘good and decent’ in honky America. We will loot and burn and destroy. We are the incubation of your mother’s nightmares!”[31] White, non-Jewish mothers, that is.

The anti-White hatred reflected in the remarks of Dohrn and Jacobs was a central theme of the council. The Weathermen debated whether killing White babies was a salutary revolutionary act, which one Weatherman affirmed in a rant before the assembly, “All white babies are pigs.” Mark Rudd said Weather doctrine was that “all white people are the enemy.”[32] A witness writing for the radical paper San Francisco Good Times commented: “The Weatherman position boiled down to inevitable race war in America, with very few ‘honkies’ . . . surviving the holocaust.”[33] Susan Stern described these bloody orations as “some of the most beautiful and moving speeches I have ever heard,” and that Jacobs’ speech (which met with much applause) “said exactly what I felt about white America.”[34]

Jacobs Expelled from Weatherman

After the Flint council, Weatherman went “underground” to wage guerrilla warfare. They formed cells in various cities. Jacobs, Rudd, Ted Gold, and Terry Robbins worked in New York. Dohrn decamped to the West Coast with Jeff Jones. The cells or “collectives” were to target police and military for attack, all subject to leadership approval. Jacobs and Terry Robbins, leaders of the New York region, were in their element. They began planning murderous bombings. Their efforts ended in spectacular failure, however, with three Weathermen killed by their own bomb in the townhouse explosion (see Ted Gold for further details).

It is very interesting how Weatherman responded to this setback. Dohrn and Jeff Jones, a couple now, plotted to take control of Weatherman and pull back from murderous terrorism. Jones, a gentile with a Quaker background, was central to this turnabout. They decided to switch to “armed propaganda,” bombing politically symbolic targets, after issuing warnings so no one would be killed. They cleverly pulled the other Weathermen to the West Coast and won them over, starting with Bill Ayers. Jacobs, however, at the following meeting, insisted on creating special “armed squads” to raise the level of struggle even higher. Yet he found little support. Even the Weathermen, in the traumatic aftermath of the townhouse disaster, thought his new plan was crazy. Finally Dohrn told Jacobs point-blank he was expelled from the organization.[35]

That night Rudd and Jacobs went out drinking:

“I’m accepting my expulsion for the good of the organization. . . . Someone has to take the blame . . . .” We talked about one of his favorite novels, Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon. “I always respected the fact that the old Bolshevik confessed for the sake of the revolution,” he told me, “there had to be a single unified revolutionary party . . . The individual doesn’t count; it’s only the party and its place in history that’s important. “At least they’re not going to liquidate me,” he said with a laugh.[36]

Jacobs then disappeared, living underground for the rest of his life.

Later Life

Jacobs wandered for several years, mostly alone, before settling in Vancouver. He took the name “Wayne Curry,” married, and had two children. However, his insistence on never surrendering to the authorities meant he chose not to re-enter politics or pursue an academic career. Hiding his real identity from everyone, he worked as a laborer, sold marijuana, dabbled in Buddhism, and even took university classes under assumed names.[37] This is a strange course of action for such a “brilliant” man. It seems he was useless without the thrill of living on the cusp of revolutionary power.

In exile he penned a revealing letter to Rudd, never mailed:

Life is admittedly lonely and sad. . . . But you can’t blame that on being a political fugitive. Life was already lonely and sad before we got involved in politics. . . . Part of what I wanted from the political movement was friends, family and community. Somehow I thought that among people who were working together for social change, the values of the better society they were fighting for would be manifest in better social relations among themselves. . . . So after I had lost, killed, alienated or driven away all my friends and comrades, I found it hard to be relevant or effective politically.[38]

He wasted his life in the “revolution.”

In 1997, just after turning fifty, he died of cancer. Some of his ashes were scattered at the gravesite of Che Guevara in Cuba. Jacobs was finally home in a Communist country.[39]

Conclusion

Where does the rage of Jewish radicals—intense, life-long, and directed overwhelmingly against Whites—come from? From “inequities” in White societies? No, for the answer to inequity would be reform, not apocalyptic destruction of the society. From the “racism” and “crimes” of Western Culture? No, for that would be to willfully ignore the soaring accomplishments of Western Man, and the sordid crimes of other cultures. The motivation of these radicals is naked hatred of Western Culture, Christianity, and Whites. Since the Jews who currently pursue the Revolution—now sitting in boardrooms and government offices—consider the religion and the culture conquered territory, they are now pressing on to their most cherished goal: a final reckoning with the Whites. This is the campaign we see unfolding in all the White lands around the world. Jacobs would be delighted to see the great progress his tribesmen have made.

Endnotes

[1] Mark Rudd, Underground: My Life with SDS and the Weathermen (New York: 2010), 14. Also see Kevin Gillies, “The Last Radical,” Vancouver magazine, November 1998.

[2] David Horowitz and Peter Collier, Destructive Generation: Second Thoughts About the ’60s (New York: Summit Books, 1990), 71.

[3] Rudd, Underground, 14-15.

[4] Horowitz and Collier, Destructive Generation, 70-71.

[5] Susan Stern, With the Weathermen: The Personal Journal of a Revolutionary Woman, ed. Laura Browder (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2007), 193.

[6] Susan Braudy, Family Circle: The Boudins and the Aristocracy of the Left (New York: Knopf, 2003), 173.

[7] Bryan Burrough, Days of Rage: America’s Radical Underground, The FBI, and the Forgotten Age of Revolutionary Violence (New York: Penguin, 2015), 64.

[8] Rudd, Underground, 15.

[9] Ibid., 21-22.

[10] Stanley Rothman and S. Robert Lichter, Roots of Radicalism: Jews, Christians, and the New Left (New York: 1982), 35: “. . . the ostensible issues were never taken seriously by the SDS leadership. According to Columbia SDS president Mark Rudd:

We manufactured the issues. The Institute for Defense Analysis is nothing at Columbia. And the gym issue is bull. It doesn’t mean anything to anybody. I had never been to the gym site before the demonstration began. I didn’t even know how to get there.

[11] Rudd, Underground, 115.

[12] Horowitz and Collier, Destructive Generation, 70.

[13] “Six Weeks That Shook Morningside: A Special Report,” Columbia College Today, Spring 1968, 37.

[14] See Eugene Methvin, The Riot Makers (New Rochelle: Arlington House, 1970), 418-21, for a good discussion of SDS provocations.

[15] Horowitz and Collier, Destructive Generation, 72.

[16] Rudd, Underground, 110.

[17] Burrough, Days of Rage, 65.

[18] Ibid., 65.

[19] Horowitz and Collier, Destructive Generation, 73-74.

[20] Ibid., 75-76; Braudy, Family Circle, 174.

[21] Ron Jacobs, The Way the Wind Blew: A History of the Weather Underground (New York: Verso, 1997), 25.

[22] Harold Jacobs, Weatherman (Ramparts Press, 1970) 53.

[23] Ibid., 51-90.

[24] Rudd, Underground, 152.

[25] Mark Rudd, “Why Were There so Many Jews in SDS? (Or, the Ordeal of Civility).” Accessed July 11, 2017. http://www.markrudd.com/?about-mark-rudd/why-were-there-so-many-jews-in-sds-or-the-ordeal-of-civility.htm

[26] John Short, “The Weathermen’re Shot, They’re Bleeding, They’re Running, They’re Wiping Stuff Out,” in The Harvard Crimson, June 11, 1970. Accessed October 14, 2016: http://www.thecrimson.com/article/1970/6/11/the-weathermenre-shot-theyre-bleeding-theyre/?page=single

[27] Gillies, “The Last Radical.”

[28] Rudd, Underground, 182; Horowitz and Collier, Destructive Generation, 90-91.

[29] Arthur M. Eckstein, Bad Moon Rising: How the Weather Underground Beat the FBI and Lost the Revolution (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 80.

[30] Burrough, Days of Rage, 85.

[31] Kirkpatrick Sale, SDS, (New York: Vintage Books, 1974), 628.

[32] Rudd, Underground, 189; Sale, SDS, 628.

[33] Harold Jacobs, Weatherman, 344.

[34] Stern, With the Weathermen, 204-06.

[35] Burrough, Days of Rage, 120-23; Rudd, Underground, 206 and 212-214; Eckstein, Bad Moon Rising, 239-42.

[36] Rudd, Underground, 214-15.

[37] Gillies, “The Last Radical.”

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

Comments are closed.