Introduction

There is a long-standing controversy over whether Karl Marx was a self-hating Jew who promoted anti-Semitism in his essay, “On the Jewish Question,” with prominent scholars weighing in on both sides of the question.[1] In my view, the position that Marx was an anti-Semite is substantiated by cherry-picked passages from his writings and correspondence and by tendentious interpretations of these passages. Here I show that the purpose of On the Jewish Question was to promote Jewish emancipation in the German Confederation (1815–1866) and thereby undermine the official status of the Christian religion, goals quite compatible with Marx having a Jewish identity and seeing his actions as advancing Jewish interests.

Is the claim that Marx rejected his Jewish heritage supported by the evidence? In a letter to his uncle Lion Philip, Marx mentioned “the fellow-member of our race Benjamin Disraeli,” a Jew he personally despised.[i] In another letter to the same Jewish relative, he wrote:

“[S]ince Darwin demonstrated that we are all descended from the apes, there is scarcely ANY SHOCK WHATEVER that could shake ‘our ancestral pride.’ That the Pentateuch was concocted only after the return of the Jews from Babylonian captivity had already been pointed out by Spinoza in his Tractatus theologico-politicus.”[ii]

These aren’t the only references Marx made to his Jewish ethnic origins. Here he indicates that he was regarded as a Jew by the Prussian authorities:

“In regard to the Cologne communist trial of 1851—in which the Prussian government sought to demonstrate the existence of a conspiracy organized around Marx—he wrote: ‘The Jew-hunt naturally increases the enthusiasm and interest.’”[iii]

Marx was also sympathetic to the plight of Jews all around the world. For example, he was outraged by Ottoman ill-treatment of Jews in Palestine. In an 1854 article for the New-York Herald Tribune, he wrote: “Nothing equals the misery and the sufferings of the Jews at Jerusalem, inhabiting the most filthy quarter of the town . . . the constant objects of Mussulman oppression and intolerance, insulted by the Greeks, persecuted by the Latins, and living only upon the scanty alms transmitted by their European brethren.”[iv]

Marx’s strong sense of Jewish group identity motivated him to help out members of his own race, even at the expense of the collective interests of the European majority in retaining Christianity as the state religion. In 1843, Marx wrote to Arnold Ruge:

“Just now the president of the Israelites here has paid me a visit and asked me to help with a parliamentary petition on behalf of the Jews; and I agreed. However obnoxious I find the Israelite beliefs, Bauer’s view seems to me nevertheless to be too abstract. The point is to punch as many holes as possible in the Christian state and smuggle in rational views as far as we can.”[v]

Like other Jewish ethnic activists, Marx sought to destroy European ethnic identity by promoting Jewish emancipation. His agenda was about “punching as many holes as possible” in the White Christian majority states of Europe, undermining their ethnic and religious cohesiveness and political stability—thus creating an environment in which Jews could pursue their own collective interests without fear of persecution. Even though Marx was contemptuous of “Israelite beliefs,” he nevertheless self-identified as an ethnic Jew. Despite his conversion to Lutheran Protestantism in childhood, Jewishness would remain central to Marx’s identity for the rest of his life.

Marx never concealed his Jewish identity. Like many strongly identified Jews in the present age, the fact that Marx was a non-practicing Jew doesn’t imply that he didn’t have a strong Jewish identification. Even his personal Shabbos Goy and longtime collaborator, Friedrich Engels, never denied that Marx was a “full-blooded Jew.” There is no evidence he was ever afflicted with any pathological Jewish self-hatred, given his willingness to sympathize with his fellow Jews, even coming to their aid in times of distress.

Did Marx promote anti-Jewish views? First, those who call Marx an anti-Semite avant la letter (i.e., before the term had originated) commit the logical fallacy of anachronism. According to Hal Draper, historians who accuse Marx of anti-Semitism are “project[ing] themselves back into history as undercover agents of the Anti-Defamation league.” He continues:

“Mainly, the allegation is supported by reading the attitudes of the second half of the twentieth century back into the language of the 1840s. More than that, it is supported only if the whole course of German and European anti-Jewish sentiment is whitewashed so as to make Marx’s essay stand out as a black spot.”[vi]

Accusing Marx of anti-Semitism ignores the fact that, in pre-Unification Germany, Jews were not discriminated against for being members of the Jewish race. If Jews wanted to escape the civil and legal disabilities they faced in White societies, they could always convert to Christianity. Marx’s anti-Judaism should not be confused with the racial anti-Semitism of Houston Stuart Chamberlain and Georges Vacher de Lapouge. He could never condemn Jewish ethnicity because it would make his demands for Jewish emancipation in European societies nonsensical. The explanation that best fits the evidence is that Marx’s anti-Judaism was motivated by a deep-seated animus harbored toward religion in general.

We shall leave these caveats aside to address the accusation that Marx was an anti-Semite avant la lettre. Does Marx’s derogatory criticisms of Lassalle as a “Jewish nigger,” “Yid,” etc., constitute prima facie evidence of anti-Semitism? Robert Fine and Philip Spencer write:

“Marx is accused of deploying racist and antisemitic epithets in private correspondence with Engels. […] In reading this private correspondence, we may accuse Marx of bad taste or chuckle at his acerbic wit but there is no evidence that he had anything other than disdain for Lassalle’s belief in physiognomy and for the authoritarian and illiberal conception of socialism of which this was part. Marx was clearly making fun of his socialist opponent.”[vii]

For Marx, Lassalle presented himself as an easy target for mockery because of a binary classification scheme reserved for Jews. There were “good Jews” i.e., the Palestinian Jews persecuted by Ottoman authorities, Jewish proletarians, Jewish socialists, etc., who were to be treated respectfully, and “bad Jews,” the money-grubbing Jewish socialists and capitalists whose traits embodied the worst features of bourgeois industrial society. If Marx saw Lassalle as a target for invective, it was because he was a “bad Jew,” a Jewish “parvenu” who “flaunted his money-bags.” There are such people.

When accusing Marx of anti-Semitism avant la lettre, historical context must always be taken into consideration. If Marx was guilty of anything, it was unfettered vulgarity during private moments with friends and family, but he was no anti-Semite avant la lettre, and certainly not by the standards of the time. He negatively stereotyped Jews, but this is not anti-Semitic when based on well-supported fact. Moreover, if anti-Semitism is defined as irrational hatred of Jews because of ethnic group membership, then there is no trace of ethnoracial hatred in any of Marx’s writings. He said and did nothing unusual for the time, apart from being solidly committed to the anti-religious values of the Enlightenment. For example, Marx allowed the French quadroon Paul Lafargue to marry his daughter, Laura. In a letter to the interracial couple, he criticized racial theorist Comte de Gobineau: “I rather suspect that M. de Gobineau, dans ce temps là ‘premier secrétaire de la légation de France en Suisse,’ to have sprung himself not from an ancient Frank warrior but from a modern French huissier.”[viii] Translated into plain English, Marx is saying that belief in White racial superiority is the province of mediocrities, an unusual sentiment for the time he lived in.

There is still the matter of the stereotyping of Jews that appears in “On the Jewish Question.” Some critics have argued that, far from being a “youthful piece of extravagant Hegelianizing which the mature Marx later outgrew,” the essay is in fact virulently anti-Semitic. Jewish academic ethnic activist Robert S. Wistrich warns:

“Marx’s intransigent hostility to religion should not blind one, however, into naively assuming that the insecurity of his own origins or the weight of his Jewish rabbinical heritage contributed nothing toward shaping the intellectual and moral character of his outlook” (1974).

The charge of anti-Semitism avant la lettre is based on a superficial, yet tendentious reading, given the aim of Marx’s critique. To understand why this is the case, let us closely examine the text of “On the Jewish Question,” which is divided into two parts.

In the first part, Marx unravels German philosopher Bruno Bauer’s belief that Jews cannot be emancipated as Jews as long as they remain members of the Chosen People. If Jewry wants political emancipation, they must first work towards the political emancipation of Germany, not as Jews, but as Germans. Marx shows this to be unworkable; in Anglo-Saxon North America, people retain their religion despite political enfranchisement. Emancipating the state from religion merely banishes it to the private sphere, without abolishing man’s predilection for religiosity. In other words, this is a plea for Jews being free to retain their religion and their status as a people apart from the Germans.

The politically emancipated state, the atheistic democracy, says Marx, is the “perfect Christian state.” Because political emancipation entails church-state separation, it no longer contradicts the Gospels, whose message is “supernatural renunciation of self, submission to the authority of revelation” and “a turning-away from the state.” The individual “religious and theological consciousness” is heightened because of political enfranchisement. The Christian majority becomes an authentically Christian one because the Christianity they embrace is without “political significance” and “worldly aims,” just as Christ had commanded in the Gospels. This shows that politically emancipating the state from religion actually backfires because it increases man’s religiosity.

Through political emancipation, the citizen is granted certain democratic rights or “rights of man,” but these also increase man’s religiousness by offering him religious freedom, instead of freedom from religion, which requires human emancipation. These democratic rights have other inherent limitations. In theory, “political life declares itself to be a mere means, whose purpose is the life of civil society.” In other words, political institutions emancipate the citizen by granting him inalienable rights; however, this is not what one observes in practice. The right to freedom of the press is completely subordinated to bourgeois interests, i.e., “human rights,” establishing political life as the aim of civil society, rather than vice versa. Paradoxically for Marx, the political emancipation granted the citizen in the form of rights is, at the same time, the negation of these rights:

“Whoever dares undertake to establish a people’s institutions must feel himself capable of changing, as it were, human nature, of transforming each individual, who by himself is a complete and solitary whole, into a part of a larger whole, from which, in a sense, the individual receives his life and his being, of substituting a limited and mental existence for the physical and independent existence. He has to take from man his own powers, and give him in exchange alien powers which he cannot employ without the help of other men.”[ix]

Political emancipation is chimerical because it reduces man to an abstraction. By substituting man’s powers for “alien powers,” political emancipation reduces “man, on the one hand, to a member of civil society, to an egoistic, independent individual, and, on the other hand, to a citizen, a juridical person.” To fully emancipate himself, man must reclaim his “own powers.” In challenging the dominance of abstraction, he combines his individual and juridical roles to develop his individuality to its maximum extent, creating a society organized around his need for self-realization. This is the human emancipation that frees egoistic man from his religious consciousness so that he becomes, in Marx’s abstruse Hegelian jargon, a “species-being in his everyday life.” This means “the ability of human beings to freely shape the material world in accordance with a consciously adopted plan that provides the essential conditions for human fulfillment” (Wartenberg, 1982).

So far, there is nothing overtly or even obliquely anti-Semitic about any of this. Indeed, Marx may well have understood that a state without an official religion, where Jews could retain their group ties, and with freedom to pursue self-realization would be an ideal vehicle to achieve Jewish interests—which, of course, is exactly what happened.

What about the second part? Marx begins by disagreeing with Bauer that the Jewish Question is necessarily a theological one:

“Let us consider the actual, worldly Jew — not the Sabbath Jew, as Bauer does, but the everyday Jew. Let us not look for the secret of the Jew in his religion, but let us look for the secret of his religion in the real Jew.”[x]

Given Marx’s approach, it is no surprise he identifies empirical Judaism with monetary exchange and huckstering. This is not mere “economic reductionism,” but well-supported historical fact:

“Julius Carlebach records that at the time of Marx’s 1843 writings small traders and hawkers constituted 66% of the Jewish working population in Prussia and the great majority of the working population in Eastern Europe. Marx acknowledged the historic role of some Jews in commerce and moneylending in pre-modern societies but saw it replaced by more systematic processes of national capital accumulation.”[xi]

Why is an empirical fact about ethnoracial differences in commercial activity construed as anti-Semitic? Marx was not alone among Jews in sharing these sentiments. Moses Hess, one of the founding fathers of modern Zionism, described Jews as “beasts of prey” who inhabited a “huckster world.” Heinrich Heine, the Jewish poet, said Israel was not known for its liberality, “save when its teeth are drawn by force.”[xii] Yet, no one would ever think of castigating Hess or Heine for anti-Semitism.

Marx continues:

“We recognize in Judaism, therefore, a general anti-social element of the present time, an element which through historical development — to which in this harmful respect the Jews have zealously contributed — has been brought to its present high level, at which it must necessarily begin to disintegrate.”[xiii]

Whereas an anti-Semite avant la lettre would have argued Jews bear full responsibility for their “anti-social” behavior — even deserving to be punished for it, Marx dismisses the nefariousness of empirical Judaism as a product of “historical development,” which may refer to standard themes in contemporary Jewish apologia, such as Jews were forced to be money lenders. The “anti-social nature” of Judaism refers to Jewish overrepresentation in financial occupations, as well as its attendant ills. For example, Jews were hired by Prussian Junkers as moneylenders and financiers; as they came to dominate these professions, their commercial immorality aroused the hatred of the peasantry. By explaining this away as the result of the transformation of feudalism into capitalism through the mysterious inner workings of the historical dialectic, Marx absolved Jews of their destructive behavior. If anything, Jews are victims of fate, despite having “zealously contributed” to their own sufferings. If Jewish behavior is historically conditioned, Jewish empirical character is not etched in stone but capable of alteration. Far from being anti-Semitic, Marx is engaged in pro-Jewish polemic.

Marx says Judaism is based on practical need and self-interest. The god of the Old Testament is the idealization of “the bill of exchange” which “is the real god of the Jew.” Marx’s analysis of empirical Judaism also applies to civil society generally: “Practical need, egoism, is the principle of civil society, and as such appears in pure form as soon as civil society has fully given birth to the political state. The god of practical need and self-interest is money.” If the bill of exchange is the “real god of the Jew,” it is the “real god” of Christian civil society as well, since it too is grounded in practical need and egoism. Civil society, despite its Christian character, is really Jewish society, where “money is the estranged essence of man’s work and man’s existence, and this alien essence dominates him, and he worships it.”[xiv]

Some have denounced the second part of Marx’s essay as virulently anti-Semitic. However, it is obvious Marx is not attacking the Jews, he’s attacking the entire bourgeois capitalist system. In doing so, the empirical Jew serves as a stand-in for the bourgeoisie’s capitalist economic interests. Empirical Judaism is turned on its head and used to point out what civil society and its members have become, a society of money-men worshiping at the altar of a money-god, i.e., the bourgeois capitalist system. If civil society and Judaism share the same material basis, then Prussians are just as Jewish as the Jews, if not Jews themselves. Empirical Judaism is Christian civil society in microcosm, since the “real nature of the Jew has been universally realized and secularized.” Marx even says:

“Christianity sprang from Judaism. It has merged again in Judaism. From the outset, the Christian was the theorizing Jew; the Jew is, therefore, the practical Christian, and the practical Christian has become a Jew again.”[xv]

Since Marx has inverted the rhetoric of the Jewish Question to critique bourgeois capitalist society, there is no longer a Jewish Question, but a Christian or Bourgeois Capitalist Question.

Empirical Judaism, Marx’s metaphor for capitalist economic activity, reached its pinnacle of development under Christian hegemony, eventually coming to dominate Christendom. Gentile civil society now embodies the nature of the empirical Jew. Christianity has now replaced man’s species-ties (his ties to the wider community) with egoism and selfishness; it “dissolve[s] the human world into a world of atomistic individuals who are inimically opposed to one another.” The bourgeois “revolutionary iconoclasm” of the Christian world-system destroys “all particulars — property, culture, family, marriage, childhood, education, country, religion, morality, occupation, personal worth” by reducing them “to a money relation.”[xvi] In Marx’s view, Christianity supplants Judaism by becoming like Judaism, but in doing so, it has become the world’s most destructive force.

Once the “emancipation of society from Judaism” has taken place, “the Jew will have become impossible.” This does not mean the extermination of the Jew, nor the dissolution of the Jewish community, as some hysterical critics have implied, such as Dagobert D. Runes’s edition of Marx’s On the Jewish Question, published as A World Without Jews for Cold War propagandistic purposes. Rather, Marx is proposing the dissolution of Judaism and the negative traits acquired by Jews, a result of their participation in the emergence of the bourgeois capitalist system.

The Jew, of course, will continue to exist biologically, as a branch of the Semitic race. Although he seldom wrote about race, Karl Marx acknowledged the reality of Jewish racial identity; in a letter to his uncle, he identified himself as being of the same Jewish race as Disraeli. He mocked characteristically Jewish racial features in his letters and writings. In the case of Joseph Moses Levy, a British newspaper publisher, Marx noted that “Mother Nature has inscribed his origins in the clearest possible way right in the middle of his face.”[xvii] Some Jews even had what Marx described as a “nastily Jewish physiognomy.”[xviii]

Conflating Jewish society with Protestant civil society serves as a literary device that allows Marx to demand Jewish emancipation and the “emancipation of mankind from Judaism,” meaning the liberation of all humanity from the oppressive capitalist economic system. Despite his seemingly “anti-Jewish” views, Marx’s conception of the role of Judaism is a positive one: “But the paradox is that for Marx, Judaism provided the basis for the liberation of modern society precisely because it was emancipation from bargaining and money that would liberate human beings.”[xix]

If Marx were a genuine anti-Semite avant la lettre, why would he be calling for the political emancipation of Jews in Germany? If he were genuinely anti-Semitic, he would have sounded much worse than post-Kantian philosopher Jakob Friedrich Fries, the closest thing we have to an actual nineteenth-century German anti-Semite avant la lettre:

“In a pamphlet titled On the Danger Posed to the Welfare and Character of the German People by the Jews, Fries maintained that the harm caused by Jews was such that they should be prohibited from establishing their own educational institutions, marrying Whites, employing Christians as servants or entering Germany, that they should be forced to wear a distinctive mark on their clothing and that they should be encouraged to emigrate. Fries’ depiction of the Jews as the enemy of the people was coupled with the revolutionary conviction that all political life must derive exclusively from the people, a category from which the Jews were excluded.”[xx]

Marx sounds nothing like Fries, who typically referred to Jews as “bloodsuckers” and “parasites.” He was not even casually anti-Semitic, otherwise his writings and correspondence would be filled with anti-Semitic slurs; instead, there is nothing even remotely anti-Semitic in any of Marx’s writings. This makes the accusation of anti-Semitism avant la lettre a laughable one. By defending Jewish emancipation “unequivocally and without conditions,” Marx is defending the “subjective right of Jews to be citizens, to be Jews, and to deal creatively, singularly, in their own way, with their Jewish origins.”[xxi]

Why some writers consider Marx anti-Semitic is mysterious. Marx is actually pro-Semitic, which is why he argues for total emancipation of the Jew in Germany, who had virtually no civil and political rights. Although he is always sympathetic to Jewish suffering, Marx is contemptuous of Judaism as a religion and as a set of economic practices. He is not contemptuous of Jewish ethnic identity, which can and will be emancipated from religious consciousness. The second part of the essay is what is usually interpreted as anti-Semitic, but this interpretation is based on a superficial and tendentious reading of the passage. The truth is that Marx’s writings were not known for their clarity and economy of language. He relied on an esoteric “Hegelianizing” to get his point across, which has confused many of his critics ever since. Fine concludes: “Marx’s early essays on the Jewish question actually ushered in a lifelong critique of antisemitism. They showed that the point of view of the Jewish question is not an inevitability; that it can be overcome. Marx’s essays remain, for all their ambiguities, a key resource for recovering a tradition of critical thought that repudiates ‘left antisemitism.’”[xxii]

Far from being anti-Semitic, Marx was a “child of Enlightenment who struggled to emancipate the Enlightenment from its own anti-Judaic prejudices.”[xxiii] Marx’s “On the Jewish Question” is really a key document in the struggle for Jewish emancipation at the expense of European majorities. Critics who dismiss Marx as an anti-Semite have not carefully considered the evidence.

Bibliography

Blumenberg, Werner. “Eduard Von Müller-Tellering: Verfasser Des Ersten Antisemitischen Pamphlets Gegen Marx.” Bulletin of the International Institute of Social History, Vol. 6, No. 3, 1951, Pp. 178—197. Jstor, Www.jstor.org/stable/44629595.

Cofnas, Nathan. “Judaism as a Group Evolutionary Strategy.” Human Nature, vol. 29, no. 2, 10 Mar. 2018, pp. 134—156, 10.1007/s12110-018-9310-x. Accessed 13 Dec. 2019.

Draper, Hal. Karl Marx’s Theory of Revolution / [Vol. 1], State and Bureaucracy. New York ; London, Monthly Review Press, 1977.

—. Karl Marx’s Theory of Revolution / [Vol. 4], Critique of Other Socialisms. New York ; London, Monthly Review Press, 1990.

Fine, Robert, and Philip Spencer. Antisemitism and the Left : On the Return of the Jewish Question. Manchester, UK, Manchester University Press, 2018, www.manchesteropenhive.com/view/9781526104960/9781526104960.00007.xml. Accessed 13 Dec. 2019.

Kaye, Howard. Social Meaning of Modern Biology: From Social Darwinism to Sociobiology. Routledge, 2017.

MacDonald, K. The culture of critique: An evolutionary analysis of Jewish involvement in twentieth-century intellectual and political movements. Westport: Praeger, 1998.

Marx, Karl. “On The Jewish Question by Karl Marx.” Marxists.org, 2019, www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1844/jewish-question/. Accessed 13 Dec. 2019.

—. “The Holy Family by Marx and Engels.” Marxists.org, 2019, www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/holy-family/ch04.htm. Accessed 13 Dec. 2019.

—. Early Texts. Translated and Edited by David McLellan. Oxford, Basil Blackwell, 1971.

— and Engels, Friedrich. Collected Works. / Volume 41, Marx and Engels, 1860-64. New York, International Publishers, 1985.

Michel, Robert. Political Parties : A Sociological Study of the Oligarchical Tendencies of Modern Democrary. New York, Free Press ; London, 1962.

Seigel, Jerrold E. Marx’s Fate : The Shape of a Life. University Park, Pa., Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

Wartenberg, Thomas E. “‘Species-Being’ and ‘Human Nature’ in Marx.” Human Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, Dec. 1982, pp. 77—95, 10.1007/bf02127669. Accessed 26 Nov. 2019.

Wistrich, Robert S. “Karl Marx and the Jewish Question.” Soviet Jewish Affairs, vol. 4, no. 1, Jan. 1974, pp. 53—60, 10.1080/13501677408577180. Accessed 21 Nov. 2019.

Read more

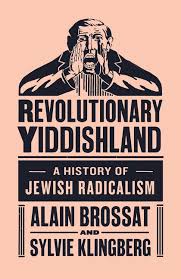

Alain Brossat and Sylvie Klingberg’s Revolutionary Yiddishland: A History of Jewish Radicalism was first published in France in 1983. A revised edition appeared in 2009 and an English translation in 2016. Intended for a mainly Jewish readership, the book is essentially an apologia for Jewish communist militants in Eastern Europe in the early to mid-twentieth century. Brossat, a Jewish lecturer in philosophy at the University of Paris, and Klingberg, an Israeli sociologist, interviewed dozens of former revolutionaries living in Israel in the early 1980s. In their testimony they recalled “the great scenes” of their lives such as “the Russian Civil War, the building of the USSR, resistance in the camps, the war in Spain, the armed struggle against Nazism, and the formation of socialist states in Eastern Europe.”[i] While each followed different paths, “the constancy of these militants’ commitment was remarkable, as was the firmness of the ideas and aspirations that underlay it.” Between the two world wars, communist militancy was “the center of gravity of their lives.”[ii]

Alain Brossat and Sylvie Klingberg’s Revolutionary Yiddishland: A History of Jewish Radicalism was first published in France in 1983. A revised edition appeared in 2009 and an English translation in 2016. Intended for a mainly Jewish readership, the book is essentially an apologia for Jewish communist militants in Eastern Europe in the early to mid-twentieth century. Brossat, a Jewish lecturer in philosophy at the University of Paris, and Klingberg, an Israeli sociologist, interviewed dozens of former revolutionaries living in Israel in the early 1980s. In their testimony they recalled “the great scenes” of their lives such as “the Russian Civil War, the building of the USSR, resistance in the camps, the war in Spain, the armed struggle against Nazism, and the formation of socialist states in Eastern Europe.”[i] While each followed different paths, “the constancy of these militants’ commitment was remarkable, as was the firmness of the ideas and aspirations that underlay it.” Between the two world wars, communist militancy was “the center of gravity of their lives.”[ii]