A Review of “Revolutionary Yiddishland: A History of Jewish Radicalism” — PART 3

The psychological impact of the Hitler Stalin pact

Radical Jewish militants were deeply traumatized by the pact between Hitler and Stalin just prior to the start of the World War II. The dilemma facing Jewish communists, the contradiction between their “visceral anti-fascism” and what was now presented to them as an imperative of realpolitik for the USSR, repeatedly cropped up in testimony of those interviewed for Revolutionary Yiddishland. One of these, Louis Gronowski, recalled:

I remember my disarray, the inner conflict. This pact was repugnant to me, it went against my sentiments, against everything I had maintained until then in my statements and writings. For all those years, we had presented Hitlerite Germany as the enemy of humanity and progress, and above all, the enemy of the Jewish people and the Soviet Union. And now the Soviet Union signed a pact with its sworn enemy, permitting the invasion of Poland and even taking part in its partition. It was the collapse of the whole argument forged over these long years. But I was a responsible Communist cadre, and my duty was to overcome my disgust.[i]

For many radical Jews, Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941 provided a sense of “relief that was paradoxical but none the less immense. They had finally found their political compass again, recovered their footing; in short, they would be able to launch all their forces into the struggle against the Nazis without fear of sinning against the ‘line.’”[ii]

In late 1941, with the outcome of the battle for Moscow uncertain, Stalin, contemplating the possibility of defeat, acted decisively to ensure the field was not left open for the former Trotskyist faction. He ordered the execution of two historical leaders of the Bund, Victor Adler and Henryk Ehrlich, just after Soviet officials had offered them the presidency of the World Jewish Congress. For Stalin, “all the militants of the Bund and other Polish Jewish socialist parties who were refugees in the USSR were considered a priori political adversaries — particularly when they refused to adopt Soviet nationality — and treated accordingly.”[iii]

These executions caused international uproar, with Jews around the world protesting, and the furor not dying down until the establishment of a Jewish organization, the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (JAC), dedicated to winning the favor of American Jews. In Culture of Critique, Kevin MacDonald notes how American Jewish leaders, such as Nahum Goldmann of the World Jewish Congress and Rabbi Stephen Wise of the American Jewish Congress “helped quell the uproar over the incident and shore up positive views of the Soviet Union among American Jews.”[iv]

Stalin controlled the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee at a distance. The JAC was headed by leaders of the Soviet Jewish intelligentsia like Solomon Mikhoels and Ilya Ehrenburg whose principal task was to “develop support for the USSR at war among Jewish communities abroad, and especially in America.”[v] Interviewee Isaac Safrin recalled hearing “on the radio that a Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee had just been set up. Ilya Ehrenburg made a great speech, very emotional, and we began to cry. The woman [he was staying with] didn’t understand what had affected us, and we had to explain to her that it was because he was Jewish.”[vi] For the six years of its existence 1942–8, the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee “stood at the center of an intense reactivation of Jewish life,” and many of the interviewees were “struck by the revival of cultural activities, even of national assertion, on the part of the Jewish community, which was encouraged by the regime in the course of the war.”[vii]

The wartime revival of Jewish identity in the USSR culminated in a revival of Zionist hopes for a reversal of Stalin’s opposition to the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. Alarmed by the “triumphant welcome Moscow’s Jews extended to the first Israeli ambassador, Golda Meir, Stalin dissolved the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee in 1948 and a few months later, prominent Jewish writers, artists and scientists were arrested, and Jewish newspapers, libraries and theatres were closed.

Golda Meir mobbed by ecstatic Jews in Moscow in 1948

Meir’s rapturous reception in Moscow reinforced that every Jew in the USSR was potentially an Israeli citizen, and that the Soviet authorities were right to distrust a community that, apart from its official nationality, bore another homeland in its heart. The authors note how:

Even in the Soviet dictionary, the word “cosmopolitan” was given a new meaning; instead of “an individual who considers the whole world as his homeland” (the 1931 definition), this was now “an individual who is deprived of patriotic sentiment, detached from the interests of his homeland, a stranger to his own people with a disdainful attitude towards its culture” (the 1949 definition). The official press poured scorn on “vagabonds without passports,” people “without family or roots,” always in anti-Semitic tones.[viii]

Stalin’s campaign against “Jewish cosmopolitans” famously culminated with the “Jewish doctors’ plot” of 1953 where leading Soviet doctors, for the most part Jews, were accused of plotting to kill Stalin. Arrested and threatened with trial, they owed their salvation to Stalin’s death (under highly suspicious circumstances) the same year. Having surveyed these events, Brossat and Klingberg view the “failure of Soviet policy towards the Jews” under Stalin as stemming from “the application of a reactionary policy that broke fundamentally with the program of the October Revolution.”[ix]

Jewish radicals who remained in Europe after WWII

For the Jewish radicals who remained in Europe after 1945, the predominant feeling was, with the defeat of fascism, history was now “on the march” and the triumph of the Red Army meant that “the great socialist dream seemed finally within reach.” The order of the day was “the building of a new society in those countries of Eastern and Central Europe liberated from fascism by the Red Army.” Brossat and Klingberg note how “these militants rapidly found themselves drawn into the apparatus of the new states being constructed.”[x]

Jewish communist cadres were “systematically entrusted with even the most senior positions in the army, the police, the diplomatic corps, economic management etc.” Jews were deliberately placed in key positions because Soviet authorities feared a resurgence of nationalism in the countries they now occupied. Jews could be trusted to carry out their plans and were seen as least likely to form an alliance with the local populace against the hegemony of the Soviets, as Tito had done in Yugoslavia. In the newly conquered nations of Eastern and Central Europe, the Soviets had few reliable supporters, and “because they were familiar with local conditions and fanatically antifascist, Jews were often chosen for the security police.”[xi] According to Adam Paszt, the Soviet authorities “knew that the population was anti-Semitic, so they tried to conceal the fact that there were Jews in leading positions.” Jews were thus “encouraged to change their names.”[xii] The authors note how:

Few of our informants could resist the siren call. Though well established in France, where he lived with his family, Isaac Kotlarz agreed nonetheless to return to Poland; he was a disciplined militant, and the party appealed to his devotion. Adam Paszt, for his part, had already lived for some years in the USSR, and although the scales had fallen from his eyes, he still had hopes. “I told myself that the USSR was a backward country, that in Poland, a more developed country, the way to socialism would be different.” Those who had been shattered by the defeat in Spain and the discovery of Soviet reality were freshly mobilized by the new situation; this upsurge of utopia, this summons from history. [xiii]

Bronia Zelmanowicz recalled that “When I returned to Poland I joined the party. Almost all the Jews did so. Some profited from the opportunity to rise higher than their abilities or their education should have let them. This was called ‘rising with the party card.’ It did a great deal to tarnish the image of Jews among the Polish population. The same phenomenon was seen in the USSR.”[xiv] The new regimes in Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia and Hungary “needed these experienced Jewish militants, who thus turned from revolutionaries into officials, privileged people in countries that had a hard time rising from their ruins.” The loyalty of these Jewish militants to the new regime was “based not only on conviction, but also on the material advantages that it gave.”[xv]

After World War II, Hungary offered an extreme example of the Jewish domination of the new regime brought to power by the Red Army. The key post of general secretary was occupied by a Jew, Mátyás Rákosi, who billed himself as “Stalin’s best pupil.”[xvi] The next five major positions were filled by Jews and a third of higher police officials were Jewish, and many departments of the security apparatus were headed by Jews. Many had spent years, even decades, in the Soviet Union, while others “had returned from concentration camps or who survived the war in Budapest” and who, as well as regarding the Soviets as their liberators, nursed “a burning desire for vengeance” against the Hungarians who had collaborated with the Nazis. Muller notes how “By moving into the army, the police, and the security apparatus, these young Jewish survivors put themselves in a position to settle accounts with the men of the Arrow Cross.”[xvii]

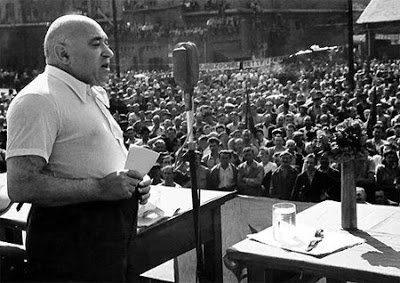

Jewish Stalinist leader of Hungary Mátyás Rákosi

Jews played central roles in building societies that “obeyed the strictest canons of Stalinism, and it was with an iron broom that the new administration consolidated its power against the ‘forces of the past,’” which involved “‘getting their hands dirty’ in this new phases of history, to bend to the Stalinist precept that you do not make an omelet without breaking a few eggs.”[xviii] The conspicuous role played by Jews in the brutal Sovietization of Hungary led to anti-Jewish riots in 1946. The oppressive nature of the new regime can be gauged by the fact that between 1952 and 1955 “the police opened files on over a million Hungarians, 45 percent of whom were penalized,” and “Jews were very salient in the apparatus of repression.”[xix]

Ultimately it was the very Stalinism these Jews so zealously implemented throughout the countries of the Warsaw Pact that served to “crush them, or at least some of them, a few years later, so that today they have the sense of a great swindle.”[xx] Stalin’s abandonment of revolutionary internationalism alienated many Jewish operatives throughout Eastern Europe. The authors note how, in the context of this new stance where internationalism tended to be “reduced to the obligatory reverence towards the guardian power, Stalin’s USSR, Jewish militants very often felt out of place.”[xxi]

Another reasons for the Jewish abandonment of the communist utopia was “the direct discovery at their own expense, not only that socialism did not put an end forever to anti-Semitism” but at times willingly used it, as in Poland in 1968, as a political tool. There an “unbridled campaign against ‘Zionists’ on Polish radio and television poisoned public life, with Jewish cadres being silently dismissed.” In 1968 restrictions on emigration were abolished and thousands of Jews left Poland. In Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Romania, the trials and liquidations of the 1950s “also had an anti-Jewish connotation, sharper or less so as the case might be.”[xxii] Pierre Sherf related his experience in Romania:

I returned to Romania with my wife in December 1945. We were at the same time naïve and fanatical. We had a deep sense of coming home, finally leaving behind our condition of wandering Jew. I was appointed to a high position in the foreign ministry, but after the foundation of the state of Israel one of my brothers became a minister in the Israeli government, and I was suddenly removed and transferred to another ministry. When Ana Pauker was dismissed in 1952, I felt the net tighten around me. My superior in the hierarchy was arrested and a case against me was opened. As in Czechoslovakia, Hungary and the USSR, veterans of Spain were fingered as “spies.” …

I never hid the fact I was Jewish, and the Party needed us, as it needed cadres belonging to other national minorities living in Romania. But it was afraid the population would resent the large number of Jews in the party leadership. Like many others, I had therefore to “Romanize” my name. I now called myself Petre Sutchu instead of Pierre Sherf. During the trials of the 1950s, the specter of “Jewish nationalism” was brandished, as in other countries. The suspicion was scarcely belied by future events. Later a member of the political bureau was eliminated because his daughter had asked to immigrate to Israel. In Spain, in the Brigades, there was an artillery unit named after Ana Pauker, but when she was dismissed, it was given a different name in the official history museums.[xxiii]

Sherf later applied for an emigration visa and left for Israel. For Jewish communist functionaries like him “the European workers’ movement and socialism had failed to resolve the Jewish question in its national dimension — not just in Europe but in the whole world.” After this failure Jewish history seemed to “present itself as an eternal recurrence founded on the permanence of anti-Semitism.”[xxiv] According to this conception, the differences between Jews and non-Jews “swells to the dimensions of an essential and irreducible alterity. As in the preachings of the rabbis, the non-Jewish world, the universe of the goyim, tends once more to become a perpetually threatening other and elsewhere.”[xxv] This sense of betrayal was the key to their subsequent disenchantment which would ultimately “lead the great majority of them far from communism.”[xxvi]

After 1948 many of the Yiddishland diaspora migrated to Israel, some reluctantly, some less so. Brossat and Klingberg note that their decision to interview only former Yiddishland revolutionaries living in Israel was arbitrary, and how the same task could have been undertaken in Paris or New York. The particular situation of their informants did, however, highlight one essential factor: “the gaping, radical break between the world that they lost and the arrogant new Sparta within whose walls they have chosen to live.”[xxvii] These onetime militants for socialist internationalism, who had “waged a bitter struggle against every kind of nationalism” now pledged their allegiance to “the state of Israel, expression of triumphant Zionism” which “has carved on the pillars of the rebuilt Temple the principles of a Manichean view of the world, a system of thought founded on simple oppositions, a binary metaphysics: just as the world is divided in two, Jews and goyim.”[xxviii]

Conclusion

Revolutionary Yiddishland is another example of that incredibly prolific literary genre: Jewish apologetic historiography. Despite this, the book is worthy of attention because, intended for a Jewish readership, its discussion of the roots and motivations of Jewish radicalism and militancy is unusually candid. It illuminates aspects of Jewish radicalism that are usually concealed from non-Jews, such as how the pursuit of Jewish ethnic interests was the primary motivating factor for Jewish participation in and support of communism in the first half of the twentieth century. When addressing non-Jewish audiences, Jews typically ascribe their disproportionate involvement in leftist politics to the impulse of tikkun olam — a desire to heal the world which naturally flows from the inherent benevolence of the Jewish people. Appeals to non-Jews to serve Jewish interests by fighting for universal “human rights” have been a consistent and incredibly successful feature of Judaism as a group evolutionary strategy in the modern era. Millions of White people (who are likely genetically predisposed to moral universalism) have been enlisted to fight for Jewish interests (and against their own ethnic interests) on the assumption they are upholding the “universal brotherhood of man.”

In the post-Cold War era, the Jewish revolutionary spirit chronicled and lionized in Revolutionary Yiddishland has been redirected into the Cultural Marxist assault on White people and their culture. As with the older generation of Jewish revolutionaries, the pursuit of Jewish ethnic interests remains the central motivation for this new revolution which revolves around the demographic and cultural transformation of European and European-derived societies. This motivation is fully evident in a review of the book by leftist Jewish activist Ben Lorber, who, placing the White heterosexual male enemy firmly in his sights, raved that “the Left faces a terrifying fascist threat unseen since the era of Yiddishland, with the rapid embrace of far-right politics engulfing Europe and culminating … with the startling seizure by Donald Trump of the most powerful political position in the world. As we combat mounting attacks on Muslim and Arab communities, black folks, immigrants, Jews, women, LGBTQ folks and more.”

Reflecting of the older generation of radical Jewish activists, Lorber insists “we have much to learn from the boundless optimism, the fearless advances and the terrifying retreats of those who struggled before.” Rather than decrying his radical Jewish forerunners as handmaidens and direct practitioners of oppression and genocide, Lorber fondly looks to them for inspiration, contending that “We need to draw hope from this previous generation of radicals who believed, against all odds, that a new sun was dawning in the sky of history. Revolutionary Yiddishland lets this generation speak, and helps us to listen.” Prey to the same ethnocentric infatuation with the “romance” of Jewish radical revolutionaries as the authors, Lorber “cannot help but look upon the passionate, almost messianic optimism of early-20th century radicals with a strange sense of dislocation and longing.”

Another Jewish reviewer extolled Revolutionary Yiddishland as “a marvelous bitter-sweet book” with the sweetness coming from “understanding the depth and vibrancy of the revolutionary socialist movement, from listening to the voice of the interviewees, and from the matter of factness of their everyday heroism and commitment.” The pro-Palestinian website Mondoweiss described the book as “a memorial to a missing world,” and claimed that “as an aesthetic composition, it is beautiful.” The Jewish Chronicle also praised the book but thought it was insufficiently apologetic and resented its “occasional anti-Zionist animus” (i.e., its very tepid criticisms of Israel) which “mars an otherwise absorbing account.”

The most telling (though entirely predictable) feature of the Jewish responses to Revolutionary Yiddishland was the absence of any reservations having been expressed over Brossat and Klingberg’s glorification of Jewish communist militants who enthusiastically founded and served regimes that destroyed millions of lives. This provides another reminder, if any were needed, that Jewish involvement with communism remains the most glaring example of Jewish moral particularism in all of history. It yet again underscores the fact that Jews have no problem setting aside moral consistency in pursuit of their group evolutionary interests.

[i] Alain Brossat & Sylvie Klingberg, Revolutionary Yiddishland: A History of Jewish Radicalism (London; Verso, 2016), 139-40.

[ii] Ibid., 141.

[iii] Ibid., 225.

[iv] Kevin MacDonald, The Culture of Critique: An Evolutionary Analysis of Jewish Involvement in Twentieth‑Century Intellectual and Political Movements, (Westport, CT: Praeger, Revised Paperback edition, 2001), xxxix.

[v] Brossat & Klingberg, Revolutionary Yiddishland, 225.

[vi] Ibid., 230.

[vii] Ibid., 232.

[viii] Ibid., 234.

[ix] Ibid., 236.

[x] Ibid., 264.

[xi] Ibid. 171.

[xii] Ibid., 267.

[xiii] Ibid., 265.

[xiv] Ibid., 267.

[xv] Ibid., 267-8.

[xvi] Ibid., 173.

[xvii] Ibid., 175.

[xviii] Ibid., 268.

[xix] Ibid. 178-9.

[xx] Ibid., 268.

[xxi] Ibid., 272.

[xxii] Ibid., 275.

[xxiii] Ibid., 375-6.

[xxiv] Ibid., 277.

[xxv] Ibid., 285.

[xxvi] Ibid., 268.

[xxvii] Ibid., 241.

[xxviii] Ibid.

Comments are closed.