Operation Excalibur: Back to Church, Bucko! Part 1

Then, He said to them, “But now…he who has no sword, let him sell his garment and buy one.” (Luke 22:36)

“Talk is for lovers. I need a sword to be king!” Excalibur Opening Scene (Battle of the Knights) 1981

Setting the Scene

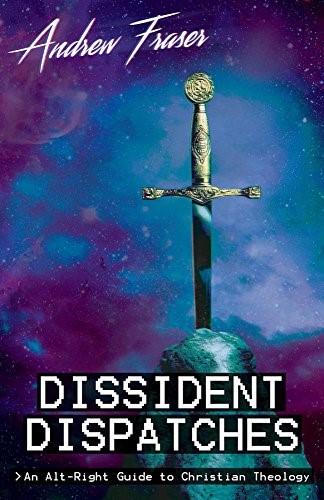

Images of Excalibur, King Arthur’s legendary sword, typically mirror the mythic iconography of the Christian Cross. Note the cosmic aura surrounding the gleaming hilt of the sword in the stone on the cover of my book, Dissident Dispatches. Its mysterious magnetism beckons the man of destiny. Only a true hero, uniquely possessed of the strength to pull the fearsome blade from the rock of ages, will be endowed with the sacred majesty of kingship. Excalibur was a fearsome weapon, striking down the king’s enemies in a spiritual struggle between good and evil. Of course, as a figment of literary imagination, Excalibur is more useful as an instrument of psychological or cultural rather than physical warfare. Accordingly, like any other popular meme, it can be deployed in cyberspace by any number of combatants, for fun or in deadly earnest.

On the Alt Right, the most famous, politically effective meme has been the seemingly innocuous cartoon image of Pepe the Frog. Amidst the tumult and confusion of the Trump campaign, Pepe helped the Alt Right movement sort out amused friends from outraged enemies. The sorting process was a two-way street, however. As part of the wider push by corporate and political wire-pullers to de-platform the Alt Right, the powerful Jewish activist organization, the Anti-Defamation League conducted a concerted, well-funded campaign of its own to brand Pepe memes as anti-Semitic and racist “hate speech”. The goal was to outlaw reproduction of the Pepe meme by Alt Right publishers, broadcasters, and bloggers. The tool chosen to achieve that outcome was copyright law. Simply for featuring Bishop Pepe on the cover of a book, Arktos Media, already well-known as a dissident right publisher, found itself the target of legal action organized by the ADL.

The response was both unexpected and disproportionate. Bishop Pepe triggered determined, well-resourced, and crafty enemies. The frog cartoon cover art was quickly leveraged into a credible threat to the survival of Arktos Media. In its campaign against Alt Right Pepe , the ADL had enlisted Matt Furie, a cartoonist who had drawn a primitive Pepe in a comic book, more than ten years ago. In the meantime, thousands of green frog images had appeared on the internet and IRL during the meme wars of 2015–2016. The ADL supported Furie in his claim to copyright ownership and hence all profits derived from the commercial use of Pepe the Frog memes. A major corporate law firm was engaged (putatively pro bono publico) to enforce Furie’s putative proprietary interest in Pepe against all the world. In practice, only parties associated in some way with the Alt Right or the Trump campaign received notices to cease and desist their use of Pepe memes and to hand over to Matt Furie any profits they may have earned therefrom. In their letter to Arktos, Furie’s lawyers threatened substantial legal and commercial penalties should the publisher not capitulate to this demand.

Faced with such an ultimatum, saving Bishop Pepe was not a major priority. After all, he was just a cartoon figure conceived in the naïve afterglow of the God-Emperor’s triumph. In the cold, hard light of day, the cover is just a lame effort to troll both the Alt Right and Christian conservatives. Almost as if both movements are just friends and allies sharing a joke. Still, there was something a bit magical about Bishop Pepe as the public avatar of the Alt Right. Whatever that mysterious something might have been, sworn enemies of the Alt Right were out to get rid of it. A cease and desist order to Amazon allowed the ADL and Furie to kill two birds with one stone: get rid of Bishop Pepe and harass a dissident right publisher (together with several other purveyors of “hate speech” in the form of cartoon frogs).

Arktos quickly replaced the Bishop Pepe cover with the Excalibur meme, but Furie’s lawyers persisted in their legal action. They claimed whatever profits Arktos earned from the sale of all copies of Dissident Dispatches with Bishop Pepe on the cover. In the real world, of course, few people decided to buy my book, having judged it by its uproariously amusing cover (or, to be frank, for any other reason). In fact, one reviewer, whose opinion I respect greatly, remarked that he was disinclined at first to read the book, just because of its cartoonish cover. The commercially trivial amount at stake in Furie’s copyright claim makes it obvious that the artist was but a stalking horse for powerful ethno-political interests pursuing an altogether different agenda.

However frivolous and vexatious the cause of action, Furie’s lawyers conveyed a credible threat of costly legal action. The relevant federal statute incentivizes legal bullying by stipulating a statutory minimum of $75,000 in damages should the matter ever come to court. Not surprisingly, Arktos chose to cough up its paltry profits from early sales of Dissident Dispatches (slightly more than $1500) just to get the ADL off its case. While Arktos may have secured temporary relief by buying off Matt Furie and his attack dogs in the ADL, the enemies of the Alt Right remain alive and well. Where, then, might the movement find friends?

Re-Awakening the Religious Right

Taken on its own, this anecdote from the contemporary world of dissident publishing is small beer. I tell the story only because I believe that Dissident Dispatches: An Alt-Right Guide to Christian Theology contains an important message, well-captured in the Excalibur meme. The message is aimed at two apparently disparate audiences: the Alt Right movement and White Anglo-Protestant Christian churches. Whether either group wants to admit it or not, we share common enemies. They are those who celebrate the imminent end of White America, even of White Britain and the formerly White dominions of yesteryear. Our enemies are recruited not just from the teeming non-White immigrant masses swamping almost every European-descended nation, truculent African-Americans, and resentful Jews but especially from the ranks of our own White, post-Christian political, corporate, and religious élites. The citadels of power have been captured by enemy forces. Not even America, much less Britain, is likely ever to be great again. In fact, America, especially, is just about over.

The Alt Right gets that; White Christians, not so much. Nevertheless, a working, informal alliance with church-goers (people typically anchored in the everyday life of civil society) offers the possibility of a new start for the Alt-Right. Reports that the Alt Right has collapsed and died have been greatly exaggerated. True, the movement is experiencing a dark night of the spirit, beached on the fringes of contemporary Weimerica. In the wake of Charlottesville, rising Antifa violence, internal scandals, multiple other mistakes, and general confusion, it is easy to lose heart. But there is still reason to hope for the revival of the ancient spirit of ethno-religious solidarity among White Anglo-Protestant peoples around the world.

Men of the Alt Right can and should recast themselves in the role of Christian cultural (maybe even holy) warriors fighting to regenerate once-Christian nations. Working body and soul to achieve such a restoration, the Alt Right might just spark another Great Awakening. Ever since the colonial era, the foundations of the established order in America have been shaken repeatedly by eruptions of Anglo-Protestant revivalism. Waves of religious enthusiasm washed over the country, fusing with contemporaneous social reform movements to spread a moralistic spirit of “romantic perfectionism”. Millenarian religious enthusiasm was an essential ingredient not just in the revolutionary war for independence but in later upheavals associated with abolitionism, progressivism, and the social gospel, not to mention feminism and prohibition. Revivalism and social reform were joined at the hip.

Nowadays, the Alt Right is an embryonic social reform movement promoting identity politics for White people. If it is ever to set the mainstream Anglo-Protestant imagination alight, it must become a religious movement. To that end, Alt Right leaders must learn how to communicate and network with the religious people to be found in Anglo-Protestant churches. There are glimmers of hope. I wrote Dissident Dispatches because I became convinced that a new Great Awakening is necessary, possible, and desirable, at least in America.

Admittedly, such a claim is rather counter-intuitive. Evangelical and mainstream Protestant churches do appear to be fast asleep at the wheel. In the face of enemies ready to fight for their faith, folk, and families, White Anglo-Protestants remain pitiably passive and apathetic. They cannot imagine how to defend the collective, ethno-religious identity they no longer possess. Protestant churches have become random clusters of atomized individuals not close-knit tribal communities. Faith is now about “growing” into a personal and private relationship with Jesus. Accordingly, White Anglo-Protestants deny the religious significance of blood and belonging. Such radical individualism stands in stark contrast to the communitarian White Christian ethno-theology outlined in Dissident Dispatches.

Making Friends and Enemies

From the activist perspective of the Alt Right, most Anglo-Protestant church-goers have “fallen asleep” (note the biblically-charged turn of phrase). They seem oblivious to the accelerating collapse of our visibly browning, once-White, now professedly post-Christian, civilization. For their own good, they should be woken up. An Alt Right mission to Anglo-Protestant churches may be just what the doctor ordered. In his review of Dissident Dispatches, Michael Lord challenges the Alt Right to seize the moral high ground by being more Christian than the Christians. In defence of every Anglo-European ethno-nation, the American Alt Right could step into salvation history, drawing Excalibur from “that spiritual Rock that followed them, and that Rock [is] Christ” (1 Corinthians 10:4). Lord asks: “Are we losing what should be an easy fight because we simply aren’t showing up for the battle?”

As the first step in that altar call, we can confess our ancestral ethno-religious identity as Christian nations. To that end, we can and should embrace an openly historical and political Christian ethno-theology. Politics is defined by the distinction between friends and enemies. Having been systematically un-friended by the powers that be, the Alt Right is becoming all-too-familiar with the existential meaning of that distinction. Far from being welcome in polite Christian company, the Alt Right more often gets the cold shoulder; no one, least of all the womenfolk, wants to talk about friends versus enemies with someone reputed to have a soft spot for Hitler. Deaf to rhetoric officially designated as “hateful,” Christian theologians and Protestant pastors instead profess their selfless, undying love for the Other. By and large, organized Christianity reserves the status of enemy for White nationalists, treating them as pariahs to be shunned and publicly denounced by true believers.

Just last year, for example, the Southern Baptist Convention passed a near unanimous resolution explicitly condemning the Alt Right as a “racist” and “White supremacist” movement. The driving force behind that resolution was a Black pastor, Dwight McKissic, Sr. As a racially-conscious, prominent Black preacher, McKissic knows well how to play the race card. In the months since he persuaded the SBC to denounce Alt Right ideas, McKissic dialled up his anti-White rhetoric. He tweeted recently that “Alt Right persons shouldn’t be welcomed as members in SBC Churches”. He made sure to personalize his exclusionary message, demanding the expulsion of Tennessee talk radio host James Edwards from his local Baptist church. How, one might wonder, can a Christian pastor justify the excommunication of White Baptists espousing constitutionally-protected religious or political views? Simply because someone is associated with the Alt Right in the mind of a Black racial activist?

One of the most valuable resources available to enemies of the Alt Right within the church is the vast reservoir of White guilt accumulated over the past seventy years. Wrapped in the moral certitude of Black liberation theology, Dwight McKissic clearly expects little resistance when he calls upon unsuspecting White Baptists to kick Edwards out of his ancestral church. He automatically pushes the White guilt button, issuing a boilerplate allegation that Edwards somehow “embraces racism & racists” on his radio show. McKissic brands both the Alt Right and fellow-travellers such as James Edwards as “enemies of the gospel”. Clearly, the gauntlet has been thrown down. Like it or not, White racial advocates who also happen to be Christians must prove McKissic and his allies elsewhere within the church wrong.

It is easy to imagine circumstances in which one’s fellow congregants might be driven in fits of pathological penitence to drive Alt Right Christians out of the church. Churches succumbing to such moral panics will embolden further the enemies of White Christian nationhood. This, of course, is nothing new. For decades now, misguided traditions of millenarian utopianism in both Protestant and Catholic churches have propped up a globalist regime hostile to the very idea of Christian nationhood. Everywhere in the Western world, global capitalism relentlessly uproots and destabilizes the folkways, faith, and families descended from White European Christian ethno-nations. The deracinated globalist faith in perpetual progress is a poor substitute for the “racist,” “sexist,” “homophobic,” and “xenophobic” faith of our fathers. Alt Right Christians must develop confidence in their ability to defend themselves in theological debates where they stand charged with heresy.

In Part Two of this essay, I discuss the biblical foundation for what might be called an Alt Right Christian political theology and how it might contribute to the next, long-overdue, Great Awakening in the political and religious history of White Anglo-Protestant churches.

Andrew Fraser is a retired law professor. For many years, he taught constitutional law and legal history at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia. He recently completed a degree in theology.

Comments are closed.