Selfish Bastards: A Review of “Atlas Shrugged, Part I”

I saw Atlas Shrugged on Saturday, April 16th. It was a sold-out showing to an all-White audience in a predominantly White area. The audience contained a large contingent of Tea Party people, mostly Christian, as well as libertarians and Objectivists. There was geeky anti-government banter as we waited for the movie to begin. There was applause after the movie ended, but I did not join in. In fact, I found this to be a deeply disappointing adaptation of the first third of Ayn Rand’s epic novel about the role of reason in human existence and what would happen if the rational and productive people—the Atlases that carry the world on their shoulders—were to shrug off their burden and go on strike.

Atlas Shrugged could be a spectacular movie. It is certainly a spectacular novel, although not a perfect one, primarily because it is deformed by the grotesque excess of Galt’s Speech, 60 odd pages in which the novel’s hero John Galt explains Rand’s philosophy of Objectivism. But I have to hand it to Rand, because at least for me, she managed to make even Galt’s Speech a page-turner. In truth, although I reject Rand’s individualism and capitalism and would not have lasted five minutes in her presence, Atlas Shrugged is one of the most audacious and enthralling novels I have ever read—and I have read most of the classics—and even it does not equal Rand’s earlier novel The Fountainhead. Atlas Shrugged is the greatest mystery novel of all, for it is about what makes civilizations rise and fall. It is the greatest adventure of all, for it tells the story of a man who stopped the world.

Although Rand opposed racial nationalism on philosophical grounds (with a sentimental exception for Zionism, of course), there is still much of value in her novels for racial nationalists. Rand started out as a Nietzschean, and her novels offer powerful defenses of aristocracy and critiques of egalitarianism, democracy, mass man, and mass society. All these elements are in tension with her later philosophy of reason, individualism, and capitalism. Indeed, Rand felt the need to reframe, revise, or simply suppress her earlier, more Nietzschean writings. But the “sense of life” of her novels is so in keeping with the spirit of fascism that her first novel We The Living was made into a movie under Mussolini, a fact that Rand later obfuscated with tall tales and a revised version of the novel. (The Italian We the Living, by the way, remains the only good film adaptation of a Rand novel.)

The Fountainhead can be read profitably alongside The Culture of Critique, for it effectively dramatizes the techniques of Jewish subversion of American society. Rand’s villain Ellsworth Toohey sums up his game as playing the stock market of the spirit—and selling short, meaning profiting from the decline of our values, which pretty much sums up the rise of American Jewry to the top of our society on a tide of smut, decadence, degeneracy, lobbying, swindling, pop culture, and casino capitalism.

Rand, of course, never saw it that way, and Rand’s own movement Objectivism is just as much a Jewish intellectual movement as the Frankfurt School. Although they use very different arguments, they function to produce the same result: a radical individualism that renders cohesive ethnic groups like Jews invisible to the majority, which maximizes their collective security and upward mobility, since cohesive collectives have a systematic advantage in competing with isolated individuals. (Rand called the mostly-Jewish inner circle of her movement “the collective.” It is supposed to be a joke, but the joke may be deeper than most people imagine.)

Atlas Shrugged, moreover, lends itself to a racial interpretation. Atlas Shrugged is about how a creative and productive minority is exploited by an inferior majority because of the acceptance of a false moral code (altruism) that beatifies the weak and pegs the worth of the strong to how well they serve their inferiors. When one asks “What is the race of Atlas?” it all falls into place. The Atlas that upholds the modern world is the White race, which is being enslaved and destroyed by the acceptance of a false moral code (racial altruism) that teaches that non-Whites fail to meet White standards only because of White wickedness, and that Whites can only expiate this racial guilt by giving their wealth and power and societies to non-Whites.

Altruism is ultimately nihilism, since when the inferior finally cripple and destroy their superiors, they will perish too. But such consequences don’t matter to locusts, parasites, and people in the grip of false values. The only thing that will save us all is a moral revolution, a new form of egoism, although I part ways from Rand on the nature of this revolution, since she is an individualist and I am a racial collectivist. Rand thinks that the individual is more important than the group, which is what you would expect of a childless woman who lived largely in her head.

Rand’s aesthetic is deeply fascist—and Socialist Realist—with its emphasis on man’s heroic transformation of nature through science, technology, and industry. Rand also had a taste for Nordic types. All of her heroes are tall, lean Nordics. Rand, born Alissa Rosenbaum, was not.

Taylor Schilling as Dagny Taggart, Vice-President in Charge of Operations for Taggart Transcontinental

The Atlas Shrugged movie is poorly cast. In terms of looks, the best choices are Taylor Schilling as Dagny Taggart, Grant Bowler as Hank Rearden, and Rebecca Wisocky as Lillian Readen. John Polito, the Italian gangster in Miller’s Crossing (“It’s about ethics . . .”), was a good choice for Orren Boyle. Michael Lerner looks great for the role of Wesley Mouch, but his personality is a bit too forceful. Matthew Marsden as James Taggart is too handsome for the part, but he makes it his own.

The worst choices are Edi Gathegi, a Black actor, for the Nordic Eddie Willers (the same actor displaced another White actor for the character of Laurent in the Twilight movies), and Jsu Garcia (couldn’t they afford a whole Jesus?), who looks like a debauched mestizo, for the blue-eyed descendant of Castile Francisco d’Anconia. The actors cast as Hugh Akston and Dr. Robert Stadler are both too young for their parts, and Stadler looks Middle Eastern and speaks with a heavy accent!

As for the acting, it is pretty much undistinguished throughout: strictly

Edi Gathegi (right) as Eddie Willers (with Matthew Marden as James Taggart and Taylor Schilling as Dagny Taggart)

soap opera grade. The best-realized roles are James Taggart and Lillian Rearden. Eddie Willers is an embarrassment. A wooden Indian would have been just as expressive and — more importantly from the producers’ point of view — even cheaper and just as politically correct. Or is there a message in casting a Black man to play a character who is essentially a faithful mediocre sidekick?

As for the script, it is shockingly pedestrian. Rand gives us an abundance of eloquent dialogue, but almost none of it is used. It soon becomes apparent why: whenever a bit of it slips in, the actors sound as wooden as Gary Cooper in King Vidor’s 1949 movie of The Fountainhead, meaning that they don’t have the brains to understand the dialogue or the skill to sell it. Rand’s dialogue is not naturalistic, but if an actor can sell Shakespeare, he can sell Ayn Rand. Tolkein’s dialogue is certainly not naturalistic, but it was faithfully adapted and beautifully delivered in Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy.

But given a cast of blockheads and Brooks Brothers models who read from teleprompters, we could not have Francisco d’Anconia’s money speech. We could only have colloquial naturalism with vulgarities like “crap” and “bullshit” thrown in. I suppose we should be grateful that we were not told that Galt’s motor was “awesome” and the Equalization of Opportunity Act “sucked.” (I wonder if the script contained emoticons. Maybe the performances would have been improved.)

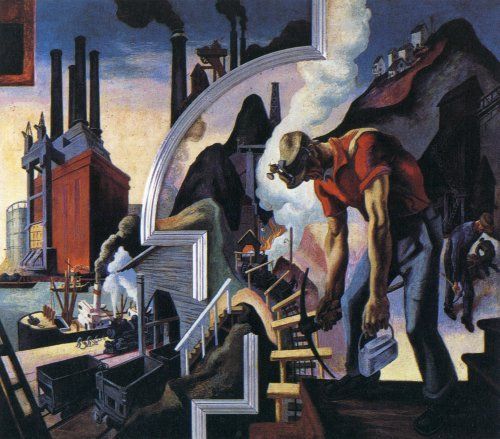

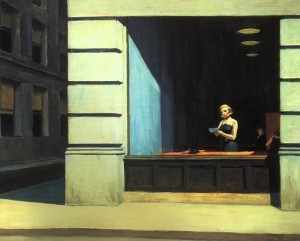

The whole look of this movie is wrong. Visually it is astonishingly flat, dull, and unimaginative. Rand’s novel requires a Brazil look: Art Deco in a vague “future”: hair and wardrobe by Tamara de Lempicka, interiors by Edward Hopper, industrial scenes from Thomas Hart Benton, casting by Arno Breker (although the men would need to be less beefy), sets by Frank Lloyd Wright, all directed by Leni Riefenstahl. Of course that would have cost money, but the real poverty in this film is of imagination and taste. Instead, we get a film set in the near future (2016 and 2017) that feels the need to explain the prominence of rail transport with an energy crisis.

The greatest aesthetic flaw of this film is the contrasting treatment of nature and industry. A film of Atlas Shrugged should glorify and aestheticize human achievement, especially heavy industry, and there is plenty of fascist, National Socialist, Socialist Realist, and New Deal art that they could have drawn upon to do this (but of course that would be “politically incorrect” from an Objectivist point of view). But instead, we have only pedestrian low angle shots of rail yards full of box cars — which might actually have been visually captivating if simply viewed from the air. The scenes of the Readen factory and the building of the John Galt Line offered many opportunities for visual splendor and dynamism, but they are pedestrian at best. The best sequence is the first run of the John Galt Line, one of Ayn Rand’s most brilliant feats of description. (This was the only scene in which I even noticed the music.) But even here the movie pales by comparison to the printed page. I was left wondering: Did the director even read this book?

The inept handling of industry is underscored by the intrusion of nature photography. Ayn Rand looked at nature as merely the raw material and backdrop of human achievement. But in the movie of Atlas Shrugged, the most beautiful scenes are of mountains and prairies. During the first run of the John Galt line, Dagny Taggart and Hank Readen’s achievements are dwarfed by the beauty of the landscape. The focus should have been on the train, the rails, the rising throb of the engines, the telephone poles rushing by faster and faster, as a vast streamlined art deco engine shot like a bullet toward the gossamer arc of the great bridge of Rearden metal. The spectacular Rocky Mountain landscape and sky should have been hidden by a drop cloth of clouds, fog, and rain.

The treatment of sex in this film is also objectionable. When Lillian Rearden asks her husband “Through are you?” as he rolls off her, there was a gasp in the theater. (James Kirkpatrick reported the same thing in his brilliant review at Alternative Right.) Talking to Tea Partiers afterward, I discovered that the gasp was due to their strongly Christian orientation. Apparently it struck them not as vicious and condescending, but simply as pretty racy stuff. Later, when Hank Rearden began his affair with Dagny Taggart, there was a less audible but still real reaction in the audience, for the same reason. The only real criticism the Christian Tea Partiers had was that the movie portrayed an extramarital affair in a positive light.

The affair is, by the way, significantly altered from the book. In the book Hank Rearden is profoundly conflicted about his attraction to Dagny, which he attributes to mere animal lust which tempts him to violate his wedding vows, which he treats as a matter of honor, even though his marriage is a loveless hell. When he finally gives in to temptation, it is one of Ayn Rand’s famous “rape” scenes. In the movie, after the running of the John Galt Line, Rearden in effect says, “Here we are, at the moment of our greatest triumph, and all I want to do is kiss you.” Dagny coyly replies, “Why don’t you then?” Cut to a tender lovemaking montage. (I could not help but think of Rand’s own parody “Sorry baby, I can’t take you to the pizza joint tonight, I have to go back to the science lab and split the atom.”) Is moral conflict and rough, passionate sex just too politically incorrect these days? Again, what were the filmmakers thinking?

Why was Atlas Shrugged made on the cheap? Apparently the producers could not come up with a script or a concept good enough to raise the money and attract the talent to do a first rate movie, and since their option was expiring, they decided to do a second rate movie instead (and managed to pull off a fourth rate one). This level of cynicism is frankly breath-taking. One has to ask: Is this how Howard Roark would have made a movie? (If this film accomplishes one thing, it will make us appreciate the 1949 movie of The Fountainhead more.)

From now on this should be referred to as director Paul Johansson’s Atlas Shrugged, for it is Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged in name only. (Johansson turns out to be every bit the director that one would expect of a soap opera hunk.) It is merely an exercise in masochism to wonder how a visionary director of epics like Zack Snyder or Peter Jackson or Oliver Stone would have brought Atlas Shrugged to the screen, because we will never know. Vidor’s The Fountainhead was bad enough that more than 60 years later, we are still without a decent film of one of the greatest American novels of the 2Oth-century. Which means that there will never be a decent movie of Atlas Shrugged in my lifetime, thanks to the selfish mediocre bastards behind this cinematic abortion.

Comments are closed.