Melvin Lasky: How a Bronx-Born Jew Engineered America’s Soft Power in Postwar Europe

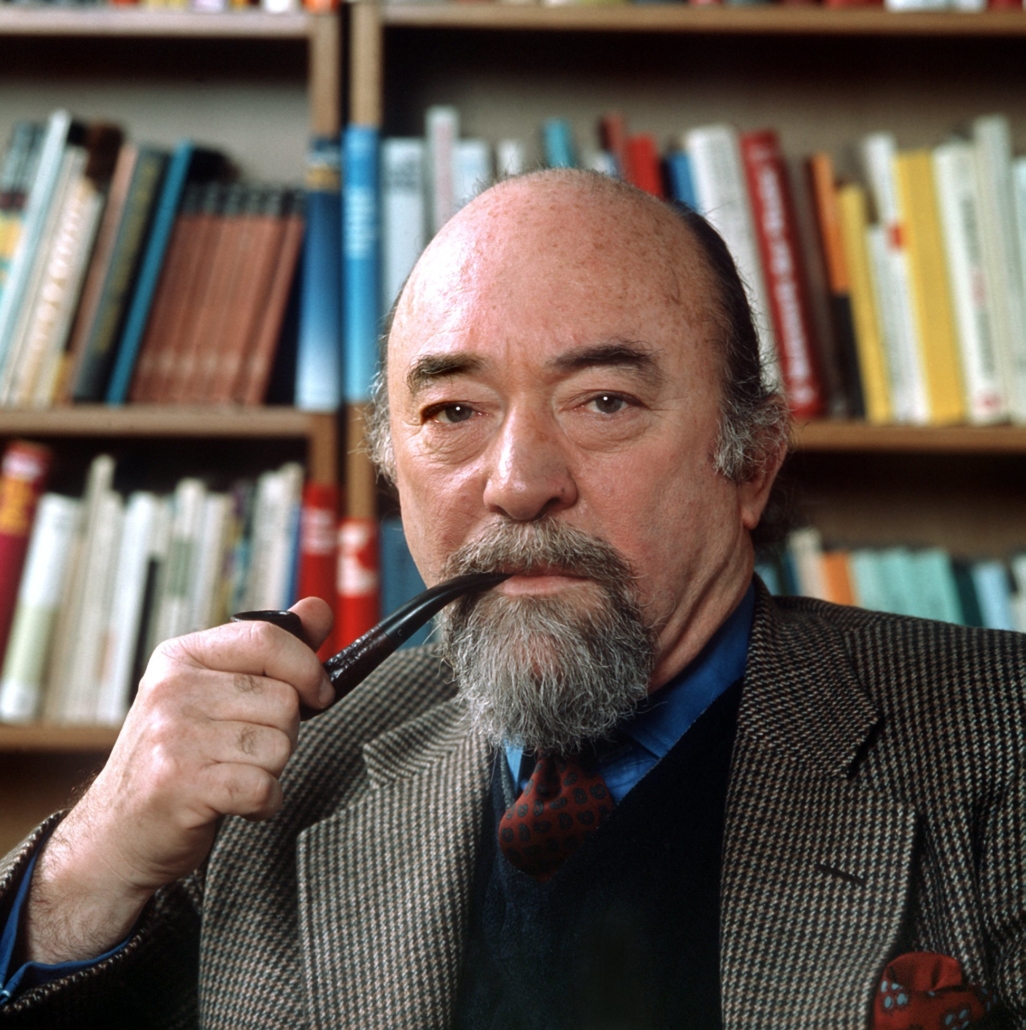

Melvin Lasky (1920–2004)

If you’ve ever wondered why American ideas travel farther and faster than American armies, the answer isn’t just Hollywood or Harvard. You can thank Melvin Lasky for that. From Berlin’s lecture halls to London’s literary circles, he perfected the art of wrapping geopolitics in glossy prose, making soft power feel like common sense while keeping the funding streams in the dark.

In battered postwar Berlin, the short, stocky New Yorker of Jewish extraction with the pointed beard made a career of seizing microphones—literally and figuratively—and turning literature into a weapon. He looked, as British historian and journalist Frances Stonor Saunders memorably put it in her book The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters, “a young American with a pointed beard and looking strangely like Lenin stormed the platform and grabbed the microphone” at the 1947 Berlin Writers’ Conference. This scene, according to some accounts, earned him the title “Father of the Cold War in Berlin.” That tableau captures the man: a militant anti-Stalinist operator who could switch tactics on a dime and function as a cultural arm of U.S. power.

From the Bronx Trotskyist to Cultural Cold Warrior

Melvin Jonah Lasky, born in 1920 to Polish Jewish immigrants in the Bronx, moved through the vibrant world of mid-century New York intellectual life. He studied at City College alongside figures like Irving Kristol and Seymour Martin Lipset, earned a history degree from the University of Michigan, and later served as literary editor at The New Leader.

As a young man he flirted with Trotskyism before, by his own account, turning decisively against Stalinism at age 22. The move from Communist dogma to the anti-Communist Left signaled more than a change in ideology. It revealed how Jewish intellectuals, once deeply embedded in revolutionary movements, could recalibrate their politics as global realities shifted. In doing so, they helped fuse anti-Stalinist ideals with the emerging priorities of American power.

World War II placed Lasky inside the U.S. 7th Army as a combat historian. His diaries from Germany, only published posthumously, revealed his shock at the Allies’ devastation of German cities and captured the moral ambiguities that would haunt postwar reconstruction. When the guns fell silent, Lasky stayed in Germany as a correspondent and subsequently as a builder of institutions.

Germany: Lasky’s New Home Base

If Lasky had a stage, it was Berlin. Saunders’ portrait is vivid, describing him as “short, stocky man” who was “given to drawing his shoulder blades back and pushing out his chest, as if primed for a fight,” using “his oriental-shaped eyes to produce deadly squints.” He brought the brusque City College manner to a city split by ideologies and armies. Saunders viewed him as “a staunch anti-Stalinist with a taste for intellectual — and occasionally physical — confrontation,” “as unmovable as the rock of Gibraltar.” Extraverted, self-confident, and aggressive — a type not at all uncommon among Jews.

Saunders highlighted some of Lasky’s flaws too, observing that he was “headstrong,” marred by “wilful deafness” and “failure to imagine the consequences of his words and actions.” In Berlin those traits cut both ways: they made him effective, and they made him dangerous.

The 1947 Writers’ Conference confrontation led directly to what became known as “The Melvin Lasky Proposal.” Addressed to General Lucius D. Clay on December 7, 1947, it dispensed with sentimental American assumptions about “shedding light” and trusting Europe to find its way:

The time-honored U.S. formula of ‘shed light and the people will find their own way’ exaggerates the possibilities in Germany (and in Europe) for an easy conversion. . . . It would be foolish to expect to wean a primitive savage away from his conviction in mysterious jungle-herbs simply by the dissemination of modern scientific and medical information . . . We have not succeeded in combatting the variety of factors—political, psychological, cultural—which work against U.S. foreign policy, and in particular against the success of the Marshall Plan in Europe.

The solution, Lasky argued, was a high-grade cultural offensive. With Marshall Plan backing, he founded Der Monat in 1948, airlifted into Berlin during the Soviet blockade. It was a German-language “bridge” journal intended to cultivate the educated classes, who tended to be socially progressive but anti-communist, on terms that would, in his words, “support the general objectives of U.S. policy in Germany and Europe by illustrating the background of ideas, spiritual activity, literary and intellectual achievement, from which the American democracy takes its inspiration.”

Der Monat quickly turned into a hub for leading intellectuals such as Hannah Arendt, T. S. Eliot, Saul Bellow, Theodor Adorno, Arthur Koestler, Ignazio Silone, and Heinrich Böll. Bundles were smuggled past East German censors. But the glossy cosmopolitan surface sat atop the murkier hydraulics of the early Cold War.

As CIA official Ray S. Cline later conceded, Der Monat “would not have been able to survive financially without CIA funds.” Ford Foundation money also flowed. Frank Wisner, the CIA’s operations chief, even rebuked Lasky for making American sponsorship of the 1950 West Berlin conference too obvious, briefly expelling him from the newly formed Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF) before rehabilitating him in 1953 to shape editorial policy across Der Monat, Preuves, and Encounter.

Encounter: Liberal Anti-Communism With Teeth

In 1958 Lasky moved to London to co-edit Encounter, inheriting a masthead built by Irving Kristol and Stephen Spender and turning it into the flagship of “liberal anti-communism.” It was, as Ferdinand Mount later said, “amazingly catholic,” open to almost any writer “with the exception of ‘Soviet hacks’.” Thomas Mann, Albert Camus, W. H. Auden, Bertrand Russell, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, and William Faulkner all passed through its pages. The magazine attacked totalitarianism, criticized U.S. missteps when it chose, and functioned as a prestige amplifier for a particular Atlanticist common sense.

Then came the controversy. In 1966–67 Ramparts magazine and The New York Times exposed the CIA’s covert financing of the CCF and its publications, including Encounter, with annual sums reportedly approaching the high six figures. A lot of money in those days.

Lasky’s reputation would be sullied by these revelations. Soon contributors to his magazines would flee, circulation dipped before recovering, and many on the New Left would treat him as a tool of U.S. imperialism. Historian Christopher Lasch argued that “the very men [such as Lasky in this case] who were most active in spreading this gospel were themselves the servants… of the secret police.”

The Architect’s Mind: Program, Network, Doctrine

Saunders’ research found that Lasky was not merely an editor, but also a systems builder. She noted that Lasky “worked at giving the Congress for Cultural Freedom a permanent footing,” drew the organizational charts, and anchored the German affiliate in Der Monat’s office. François Bondy called him “the editorial adviser of our time par excellence.” That judgment fits what we now recognize about the early Cold War. At that point in history, the decisive contest was not just armies and tanks, but syllabi, reading lists, salons, and prizes—cultural capital marshaled to ensure the primacy of the liberal capitalist order.

This is also where Lasky’s biography meets a longer arc of political adaptation. Many Jewish intellectuals moved from the radical Left to the anti-Communist Left without losing the moral fervor that had energized their youth. Lasky’s switch was not a retreat from politics; it was a redeployment. He had no illusion about the stakes. As he told General Clay, “whilst the Soviet lie was travelling round the globe at lightning speed, the truth had yet to get its boots on.” If the United States wanted to win, it needed institutions that could run just as fast as the lie.

From CCF to NED: The Template That Wouldn’t Die

The CCF collapsed in scandal, but its playbook lived on. During the Reagan era, Washington’s neocon-staffed National Endowment for Democracy (NED) (founded by Allen Weinstein and Carl Gershman who was president from 1983 to 2021) and its satellite institutes were widely understood—even by supporters—as a way to do in the open what the CIA once paid for in the shadows, such as funding parties, unions, media, conferences, and “civil society” to shape political outcomes abroad. As one critical account put it, NED and the broader democratization push sought to revive the post-WWII international networks of congresses and publications that the CIA had quietly underwritten—networks in which Irving Kristol and Melvin Lasky were leading figures.

The line from Der Monat and Encounter to color revolutions and NGO-sponsored regime change may be neither straight nor singular, but the family resemblance is impossible to miss. Put bluntly, the CCF taught Washington how to launder persuasion as culture, and subsequent institutions perfected the method.

That is why Encounter is often called the intellectual forefather of both modern neoconservatism and large swaths of mainstream liberalism. From 1953 onward, backed by covert American and British funds, it forged a cosmopolitan sensibility that treated Atlantic alignment as common sense and nationalism or neutralism as atavism. Even admirers who stood outside those camps have conceded its power; political writer Michael Lind once called it “the best magazine of ideas ever, full stop.” Influence on that scale is not accidental. It is engineered.

The Man and the Method

What, then, is the fairest verdict on Lasky? He could be generous; he could be ruthless. He also accepted, and at times helped structure, covert state funding that compromised the very independence he professed to advance.

Saunders captured Lasky’s true nature, observing he was “lupine, grittily determined” and had “an irritating habit of grinning ‘like a Cheshire cat’ every time he scored a rhetorical point.” He relished the fight. But his “willful deafness” to the downstream consequences of secrecy helped hand his enemies a cudgel. In the end, his magazines did more than critique totalitarianism; they naturalized a pro-American worldview inside Europe’s thinking classes. That outcome served U.S. imperial interests exquisitely—exactly the effect a consummate asset is supposed to deliver.

Lasky died in Berlin in 2004, having edited Encounter until the Cold War’s dusk and received civic honors from the city he once tried to rewire. His legacy is not simple, and it shouldn’t be sanitized. He shows how swiftly Jewish political operators can pivot when circumstances change — interests, not principles. Moreover, Lasky demonstrated how, in the crucible of the Cold War, a cohort of Jewish intellectuals who once trafficked in radical critique repurposed that same energy for an anti-Communist project inseparable from American power. That agility was not hypocrisy; it was strategy. It built the infrastructure—journals, congresses, fellowships—that later reappeared, more openly branded, in institutions like NED.

In Berlin, Lasky learned that ideas win when they come wrapped in glamour and when the check clears. He also learned that the public will forgive many things—except discovering, years later, who signed the check. The lesson for our era is not to moralize after the fact, but to recognize the method when we see it. Culture is never neutral. And in the long war of ideas, Melvin J. Lasky was less a bystander than a field officer, calibrating tone and talent to keep Europe inside the American orbit.

The record shows a man who blurred every line between journalist, propagandist, and agent of influence. Call him editor if you like; in practice, Lasky did the work of a Jewish operator—constantly at odds with gentile society.

“Constantly at odds with Gentile society” seems an overstatement. True, that one issue of his ENCOUNTER had nearly all Jewish contributors & was nicknamed ENKOSHER. However, it was a useful, interesting, well-written and informative magazine, CIA backing notwithstanding, and full of useful exposures of Communist ideology, deception and malpractice, and “black power” and “pre-DEI” likewise. His 12-year co-editor Anthony Thwaite was very English; Stephen Spender much less so, of course. Lasky’s book on “Utopia & Revolution” is scholarly and valuable.

Stop idolizing the jews.

Their ideas are all laughable crap.

It’s their connections and money that make them legit and spread them around or else.

I don’t idolize anyone. My joke about “Encounter” proves otherwise. Yes, money has been a major factor in Jewish influence, notably in finance and media, and damage done by Likudniks and their diasporic claque. I don’t suppose you have studied “all” or even many Jewish writers, and presume your view is a general prejudice rather than a consequence of study. Lasky’s explanation of Marx’s Jewishness, for instance, is quite relevant. Maybe you should make a start by reading a few “antisemitic” Jews, such as Spinoza, Lazare, Weininger, Oscar Levy, Arthur Trebitsch, Israel Shahak, Norman Finkelstein, Paul Gottfried, Gilad Atzmon & Gerard Menuhin, perhaps in reverse order as your presently closed mind gradually opens.

People think the jews are great thinkers with great ideas only because on the totality of the media-sphere since the 60s there’s not much else to be found other THAN jewish ideas.

Zeitverschwender

Are the ideas of Raymond Aron, Isaac Asimov, Niels Bohr, Alan Fersht, Lise Meitner, John Von Neumann, Nicolaus Pevsner, Steven Pinker, Max Scheler or Milford Wolpoff, to select a few, all “laughable crap”?

Your point? No one here says no Jew ever has good ideas.

@ TOO Editor

Someone here said that the ideas of Jews are “all crap”.

My point was to challenge that ignorant generalisation.

Nor are all Jews “sadists” as asserted on another thread.

Almost everyone can come up with a list of people whose ideas are far superior to the ideas of the jews you mention. Yet, noone has ever heard of these men. And that’s my point exactly.

@ Evangelos Aragiannis

Please list your superior non-Jewish people “no-one has ever heard of”. So we can read them. Meanwhile, I shall make do with Aristotle, Plato, Ibn Khaldun, David Hume, Francis Galton, Gustave LeBon, William McDougall, Nietzsche, Spengler, Heidegger, Pitirim Sorokin, Roger Scruton, etc.

Ah, reading this thread, I can not escape bringing to mind Philo of Alexandria screaming out of his lungs that Homer and Plato were shameful Torah plagiarists and of course my ears are still ringing by the Athenian greeks’ giggles listening to Paul’s assertions trying to sell his hebraic produce aka …….

TOO readers may need hygienic gloves or miniature tongs but might learn something about Marx(ism) from Julius Carlebach’s “Karl Marx & the Radical Critique of Judaism” (1978) noting Hitler and Weyl, among the boundless literature on Old Whiskers and his legacy. Gentiles and Jews alike have seen Marx as a secular version of an Old Testament prophet, and Jewish communists as moved by a messianic utopianism as well as revenge against host(ile) societies. An interesting sample of a contrarian angle by a Zionist is Daniel Swindell’s “The Left’s Hatred of Israel began with Karl Marx,” The Times of Israel, February 5, 2020, online. Like real life, these matters are simple only to simpletons.

Regarding the malodorous “Moor” as a “modern Moses” I neglected to add Robert Wistrich’s “Revolutionary Jews from Marx to Trotsky” (1976) which discusses this view briefly at the outset of this well-documented and important book.

@ Brian Rockford

I couldn’t find in the mountainous annotation of Carlebach’s tome any comment on Nathaniel Weyl’s (now expensive) “Karl Marx Racist” (1979) which is nevertheless worth reading.

In respect of …not in spite of a number of brilliant commenters on this thread…did any Jew ever equal the contributiions of Nikola tesla? Nikola Tesla made that fraud rapist plagiarizer einstein look like a piker..*

Nikola Tesla did say *Never Trust The Jew*among a number of other incisive

pungent comments on the JQ. By the way..Prof.KM was spectacular on the very recent Red Ice podcast.

Professor Iwan Morus shows in his biography that Tesla was superior to Einstein even as a showman.

This brilliant “Electrician” was also a Eugenicist, like other great minds of the time.

Tesla was also one of the great minds who advocated Eugenics.

These great minds then went right across the political spectrum: Irving Fisher, Ronald Fisher, Karl Pearson, Maynard Keynes, Hermann Muller, Julian Huxley, Teddy Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, Alexander Bell, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Ruggles Gates, Leonard Darwin, Sidney Webb, Jack Steinberg, Dean Inge, Corrado Gini, Mare Stopes, Bertrand Russell, Harry Emerson Fosdick, William McDougall, Pan Guangdan, Bishop Barnes, George Chatterton-Hill, &c.

For the failure to follow their advice, “si monumenton requiris, circumspice”.

Several commentators have seen the Bible/Jewish “history” reflected in Soviet Communism, including Jules Monnerot, Northcote Parkinson, and Bertrand Russell who matched up Marx with the Messiah.

The JQ relationship to Bolshevism has been bedevilled by both Jewish disinformation and Anti-Jewish misinformation. A glaring yet instructive example appears in the prolific professor Walter Laqueur’s “Russia and Germany” (1965). He describes Colin Jordan’s “Fraudulent Conversion” (1955) as repeating “most” of the “Protocols of the Elders of Zionism” which is simply not the case. He accuses him, also inaccurately, of branding “all” the leaders of Communism “as Jews” with the “possible exception of Stalin”. In fact, Jordan contrariwise claims that Stalin was in fact a Jew, basing this on an anecdote from an ex-communist exile from Georgia whose real name was Suren Yerznykyan, and on an all-too frequent gross mistranslation of the dictator’s original surname Djugashvili. Another alternative but equally mythical “Jewish” explanation of this name was presented by an anti-communist Jewish scribbler whose real name was Josef Heisler. Stalin’s paternity was always dubious, however, and it is nevertheless possible that he had some quite remote “Mountain Jew” ancestry. Jordan mispresents the post-WW2 attack on “Zionists” in the Soviet sphere as an attack by Jewish rulers on ideological rivals, ignoring the diminution of Jewish personnel and influence.