A Critique of Thomas Carlyle’s “On The Nigger Question:”

A Reactionary Reading of Carlyle’s Most Outrageous Essay

“Well, you shall hear what I have to say on the matter, and probably you will not in the least like it.”

– Thomas Carlyle, “Occasional Discourse on The Nigger Question”

◊

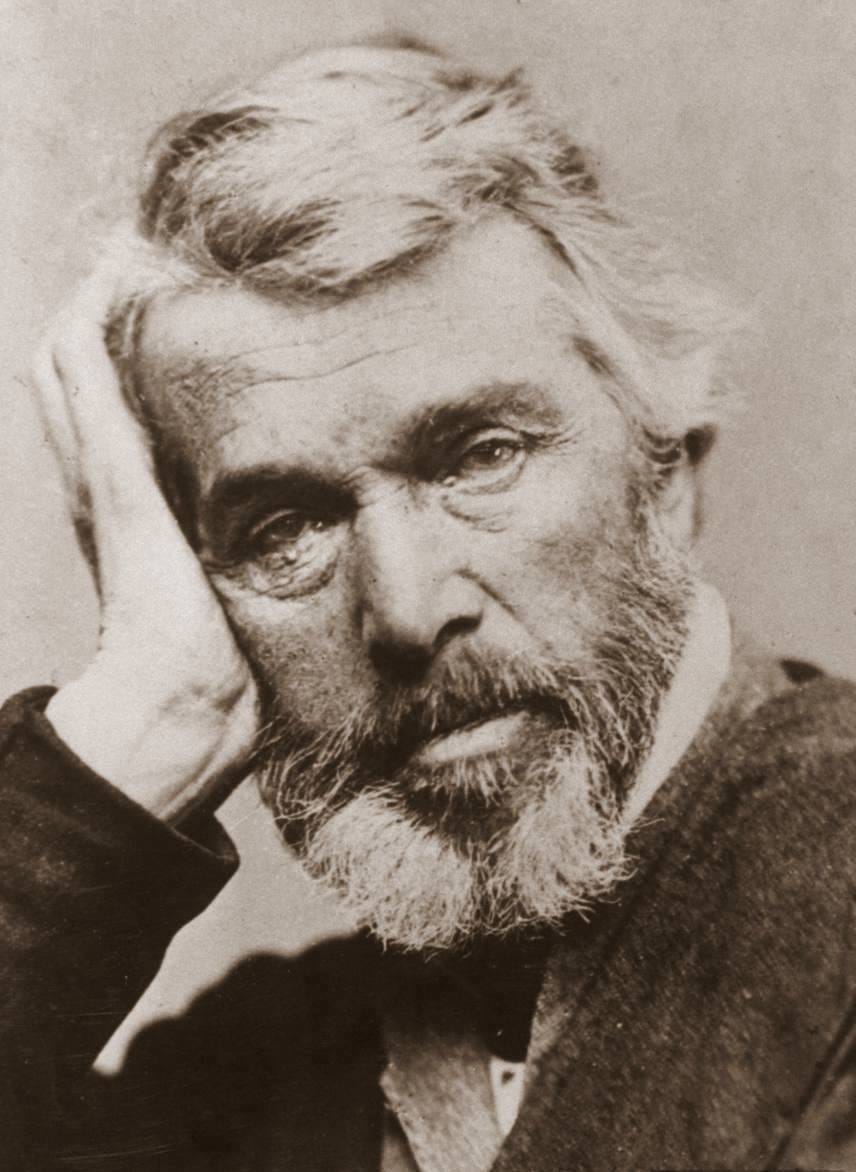

Although he has fallen into relative obscurity after 1945, Thomas Carlyle remains one of the most important thinkers in British literature, philosophy, and history, and certainly a preeminent thinker among his Victorian era contemporaries. Indeed, he became known as “The Sage of Chelsea,” a moniker that persists to this day. Others lauded him as “the secular prophet.” Although he was never a novelist, familiarity with his seminal works is foundational to any understanding of Victorian thought and literature. Indeed, both Sartor Resartus and On Heroes and Hero-Worship remain among this author’s very favorite works of all time. “Shooting Niagara, and After?” stands as a largely irrefutable indictment against democracy. Past and Present is also excellent. Carlyle of course also wrote tremendously influential histories on both The French Revolution and Friedrich the Great.

The Sage of Chelsea was fiercely anti-egalitarian and understood the importance of hierarchy, and for the most part espoused a natural hierarchy based on merit and ability, although he, like other great thinkers, has had difficulties in ascertaining how such a natural hierarchy can be fairly and perfectly established and maintained. He was also an acute Germanophile, often using fictional German names as mouthpieces, from Diogenes Teufelsdröckh to the more obscure Professor Sauerteig in Past and Present. It should thus hardly be a surprise or a coincidence that English departments in German universities in the 30s and up to 1945 produced an inordinate number of doctoral dissertations and other publications on his writings.

Many of Carlyle’s suppositions remain antithetical to received orthodoxy in the modern world, most particularly his anti-egalitarianism as well as his open and, this author would suggest, righteous contempt for democracy. However, among all his controversial works and statements there is doubtlessly no greater affront to modern sensibilities than his essay “Occasional Discourse of the Nigger Question.” The essay was originally published anonymously in 1849 in Fraser’s Magazine as “Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question.” While both the subject and the title of both versions defy credulity of most modern readers today, it was a scandal in Carlyle’s own time. Rather than backtrack or prostrate himself with some groveling apology, he renamed the essay “On The Nigger Question,” along with adding some important revisions. Most crucially, the earlier version of this essay is still more widely available under its original name, “On The Negro Question” (including in a hardback anthology owned by this author); “On The Nigger Question” is revised and extended significantly from the earlier version of the essay with a slightly more agreeable name. Thus, anyone interested in reading this most controversial essay must procure this later edition, regardless of how offensive and iconoclastic its title may be to many.

Many, even those fond of Carlyle’s other writings, shy away from the essay not because of epithets or anachronistic language, but because the essay is purported to stand as a defense of slavery. To characterize this tract as such is not even an oversimplification, but an outright mischaracterization, as demonstrated towards the end of this critique. “On The Nigger Question” is just one of the off-the-shelf indictments of Thomas Carlyle modern sorts use to impugn not just Carlyle but those who read him. That a prominent Scotsman and thinker who lived in Victorian Britain has views about race that are antithetical to modern norms should be a novelty to precisely no one. A person who has not read this essay might conclude that it has little relevance to the modern world. To the contrary, the essay is remarkably salient even today, brings up, at least at the most abstract, philosophical level, pressing, seemingly intractable matters that are still relevant today, almost two centuries later. It may be difficult for all but a handful of readers to overlook something that defends slavery, or rather is purported to defend slavery, but the issues raised by the Sage of Chelsea implores modern readers to do so. For Europe and the West are still possessed by the same pathological altruism that drove abolitionism, and, more importantly, these intractable problems Carlyle cites that have arisen as a result from the same motivations and ideals. Quite poignantly, Carlyle warns that “the terrible struggle to return out of our delusions” is “leading Europe” to the abyss; “Europe” is “floating rapidly, . . .nearing the Niagara Falls.” Alas, it seems she already has long since gone over Niagara and is not likely to survive.

The outrageous tract is written with the beautiful but dense prose that is so utterly and singularly characteristic of Carlyle. While certain diversions into German transcendentalism and other matters render certain portions of Sartor Resartus inscrutable to even more sophisticated readers, this essay presents no such challenges to any appreciable extent. However, as with all Victorian prose, the text is far more challenging than the dumbed down bile that passes as writing in the modern era. The tract is dripping with that certain sardonic wit and biting rhetoric that is quintessential to the writings of Thomas Carlyle. He mocks and derides abolitionism with the moniker “The UNIVERSAL ABOLITION-OF-PAIN ASSOCIATION!” The essay presents the reader with a fictional account of an address to Exeter Hall by an unnamed speaker, as recounted and written by a failed journalist “Phelin M. Quirk,” with the tract recounted as being found by his landlady after the journalist absconded due to inability to pay rent. This biting attack on journalists is only the first morsel that many readers will find highly relevant to the modern world. “Journoscum,” as they are known in Internet parlance, are as they always have been, it seems. Surpassing 4chan edgelords who would live centuries later who conjured “farm equipment” as a racial epithet, Carlyle derides “Demerara negroes” as “two legged cattle.” Far less controversial, the pejorative phrase “the dismal science” applied to economics was coined by Carlyle in this very essay.

The essay, both as it initially appeared in 1849 and revised and retitled in 1853, was written in the aftermath of the Demerara slave rebellion and some time after the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 that had been enacted. That body of legislation abolished slavery in most all of the British Empire. Similarly, the abolitionist movement that had overtaken Great Britain some time ago was gripping large contingents of The United States, a fervor that would delve the latter into a civil war, or war between the states for those so inclined, killing hundreds of thousands of people, and horribly maiming many thousands more. It is of note that, in “Shooting Niagara,” Carlyle describes the abolitionist movement and The American Civil War that resulted as Schwärmerei, warning of the dangers of mob rule and mass hysteria that can take hold in democracies; the word means “swarmery,” as many might guess, but in German is a derisive term used to denote irrational but exuberant mass hysteria.

In “The Nigger Question,” the anonymous speaker who outrages the crowd at Exeter Hall recounts a state of affairs in Demerara where no cash crops are grown or can be planted. This is because, in the wake of the 1833 Abolition Act and a subsequent reform ending abuse of an “apprenticeship period” that had been allowed initially, freed slaves refused to work, particularly because they could grow pumpkins with practically no effort or labor.1 In sharp, biting prose that seems to channel future racial stereotypes about watermelon and fried chicken, Carlyle, using this anonymous speaker as his mouth piece, recounts freed slaves lying around in idle sloth, consuming prodigious quantities of pumpkins that, at least in the short term, grow in the fertile soil with little to no labor:

[A]nd far over the sea, we have a few black persons rendered extremely “free” indeed. Sitting yonder with their beautiful muzzles up to the ears in pumpkins, imbiding their sweet pulps and juices; the grinder and incisor teeth ready for ever new work, and the pumpkins cheap as grass in those rich climates; while the sugar-crops rot round them uncut, because labor cannot be hired, so cheap are the pumpkins. . ..

One of the first and most relevant contentions lodged against the abolitionist movement and the resulting state of affairs is the crazed Scotsman’s account of the plight of Britain’s own sons and daughters. He writes that while “the Negroes are all very happy and doing well,” whites in the West Indies colonies are “far enough from happy. …” Carlyle further expounds on the plight of Britain’s own sons and daughters on the home island, ignored by abolitionist preoccupation with the plight of blacks:

[T]he British Whites are rather badly off; several millions of them hanging on the verge of continual famine; and in single towns, many thousands of them very sore put to it, at this time, not to live “well,” or as a man should, but to live at all. . .. But, thank Heaven, our interesting Black population, — equaling almost in number of heads one of the Ridings of Yorkshire, and in worth (in quantity of intellect, faculty, docility, energy, and available human valor and value) perhaps one of the streets of Seven Dials, — are all doing remarkably well.

This has so many parallels to the do-goody, pathological altruism of today that one can scarcely keep count. Almost two centuries ago, it was the plight of slavery. Today, the same misguided concerns for the other, the racial interloper and imposter, as opposed to one’s kith and kin, is directed toward a plethora of matters, from hordes of third world invaders both at the Southern border and that are making incursions all throughout Europe, to Christian missionaries who focus their efforts evangelizing dark Africa while whites suffer any number of maladies and vices, from drug addiction, to homelessness, to suicide.

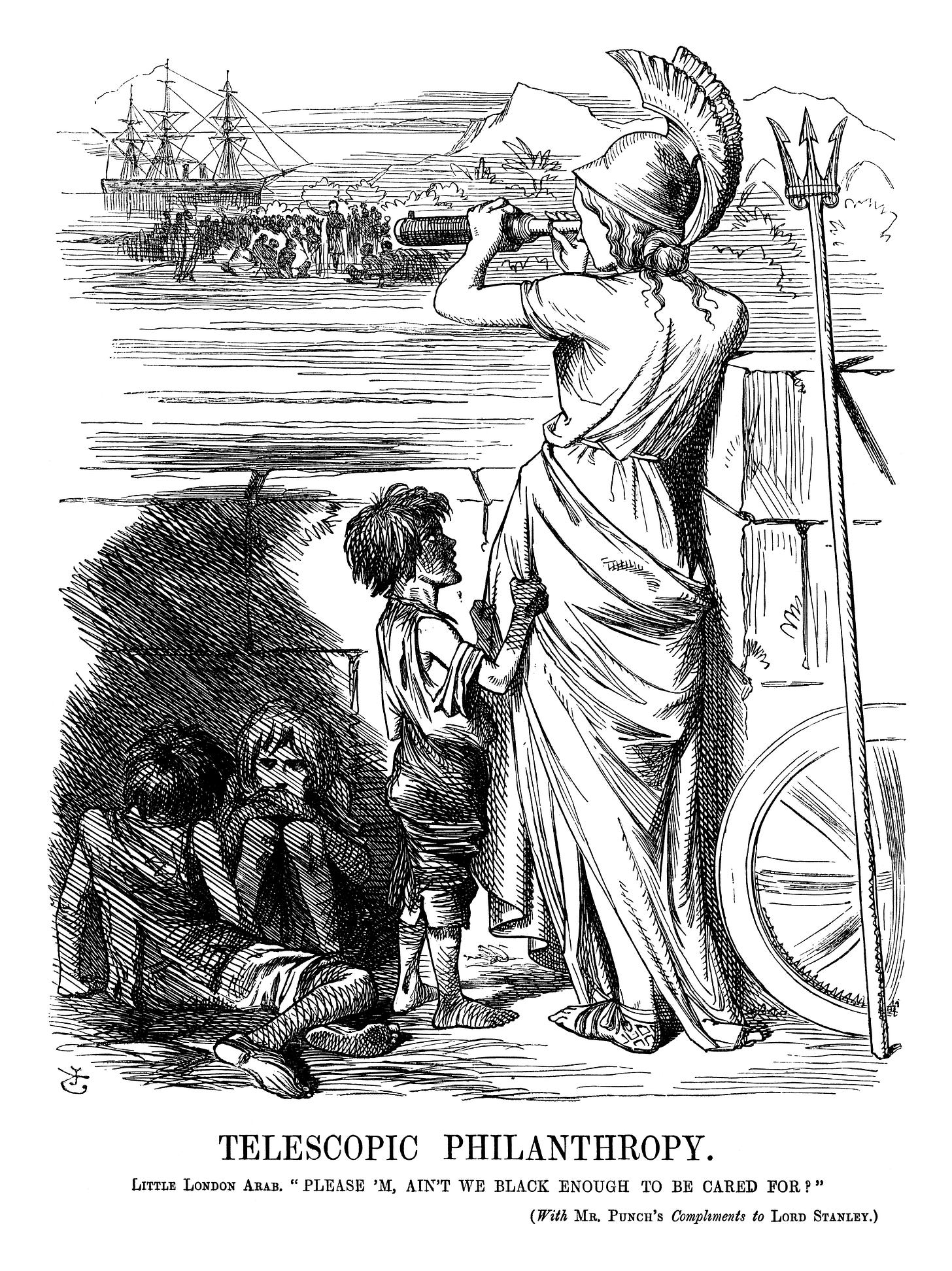

This objection to what a political cartoon of the time coined as “telescopic philanthropy” is bolstered by Carlyle’s assertion that British imperial designs and interests take far greater precedence than abolitionist sensitivities or misguided concerns for the welfare of blacks. Carlyle reminds the reader of the cost in blood and treasure in acquiring and maintaining colonial possessions:

Before the West Indies could grow a pumpkin for any Negro, how much European heroism had to spend itself in obscure battle; to sink, in mortal agony, before the jungles, the putresences and waste savageries could become arable, and the Devils be in some measured chained there!

He then offers this detailed account of the actual potential for these colonial possessions, if the British population were not hampered by such mad delusion:

The West Indies grow pine-apples, and sweet fruits, and spices; we hope they will one day grow beautiful Heroic human Lives too, which is surely the ultimate object they were made for; beautiful souls and brave; sages, poets, what not; making the Earth nobler round them, as their kindred from old have been doing; true “splinters of the old Harz Rock;” heroic white men, worthy to be called old Saxons, browned with a mahogany tint in those new climates and conditions. But under the soil of Jamaica, before it could even produce spices or any pumpkin, the bones of many thousand British had to be laid.

It is on this solid foundation Carlyle asserts that Britain should and must “refuse to permit the Black man any privilege whatever of pumpkins till he” agrees to “work in return.” Carlyle further reasons that but for European genius, enterprise, and imperialism, “Quashee” would never be in a position in the West Indies to enjoy pumpkins. The “Sage” reasons as follows:

Never by art of his could one pumpkin have grown there to solace any human throat; nothing but savagery and reeking putrefaction could have grown there. These plentiful pumpkins, I say therefore, are not his: no, they are another’s; they are his only under conditions.

He further implores that “Not a square inch of soil in those fruitful Isles, purchased by British blood, shall any black man hold to grow pumpkins for him, except on terms that are fair towards Britain.”

This directive is uttered in the context of repeated allusions to crop failure and failure to plant and produce cash crops that are of vital importance to The Crown and Empire. Carlyle correctly argues such concerns should be the prime directive, not “Exeter Hall Philanthropy” and sentimentalism:

No; the gods wish besides pumpkins that spices and valuable products be grown in their West Indies; this much they declared in so making the West Indies;-infinitely more they wish, that manful industrious men occupy their West Indies, not indolent two-legged cattle, however “happy” over their abundant pumpkins!

Stated more succinctly:

“The State wants sugar from these islands, and means to have it; wants virtuous industry in the Island and must have it.”

It is unclear to this author, absent the advent of modern agricultural technology, how these vital interests of the Crown and Empire could be realized without slavery or compelled labor of some sort. While this may offend or at least perturb even the more hardened readers of this publication, it is a central objection Carlyle raises that seems to have no easy answers.

Consider however what the reward has been for abolitionist folly and other such humanitarian sensibilities, mindful of course that Britain undertook massive debt to pay for abolition of slavery within its dominion in The Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, a debt it only recently paid off in 2015. The reward is demonization of whites, justification for the reverse colonization of the British Isles — the ancestral motherland of those of Anglo, Scottish, and Celtic descent in the Anglosphere — as well as Europe writ large and the Anglosphere nations of The United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand as well. In the United States particularly, blacks collectively never express appreciation for the blood and treasure that was expended in the name of their emancipation. Despite trillions foolishly squandered in Great Society programs, the establishment of an onerous regime of civil rights laws which distort and supplant much of the original understanding of certain freedoms in the Bill of Rights, a critical mass of the black population drone on with demands of reparations with ever increasing zeal and fervor.

Such considerations in turn call to mind this very admonition offered in the pages of this controversial tract:

Up to this time it is the Saxon British mainly: they have hitherto cultivated with some manfulness: and when a manfuller class of cultivators, stronger, worthier to have such land, abler to bring from it, shall make their appearance, — they, doubt it not, by fortune of war, and other confused negotiation and vicissitude, will be declared by Nature and Fact to the worthier, and will become proprietors, — perhaps also only for a time.

If the insidious designs of the Great Replacement are successful and white Europeans are largely extinguished from the face of the Earth and Britain and Europe most particularly, hegemony will simply pass to either the Muslim world or more probably China. China’s neocolonial ambitions in Africa are replete with accounts of brutality that are no more for the faint of the heart than the worst abuses of European slavery were. This is compounded by the fate of the Tibetans and Uyghurs under Chinese rule. But whereas Britain in particular and the Anglosphere more broadly worked itself in a lather with humanitarian folly, China, in a century’s time or more, will have no such delusions. If Anglos in particular are vanquished, such humanitarian tendencies will have contributed to their extinction, imploring the conclusion among Chinese historians that the since-vanquished pale faces ought to have been more far more brutal and far more ruthless. This eventuality, too, is even foretold in this passage of Carlyle’s most outrageous essay:

“Quashee, if he will not help in bringing out the spices, will get himself made a slave again (which state will be a little less ugly than his present one), and with beneficient whip, since other methods avail not, will be compelled to work.”

Admittedly, this passage seems to envision a British Empire slightly less inclined to such humanitarian fancies, but given the preceding warning above that the mantle of hegemony can and does shift from one race and civilization to another, this dire warning most directly portends the coming specter of Chinese, Islamic, or other such hegemony, which will assuredly not suffer from such fatal flaws of pathological altruism as the pale faces of Britain particularly and Europe more generally.

Carlyle’s most outrageous, untouchable essay is relevant in other ways. In complaining about blacks consuming pumpkins, he raises a consideration that directly relates to the wildly disproportionate number of blacks benefitting from the welfare state, representing a net deficit per head, on average and in the aggregate. This assertion is first predicated on the state of affairs as described:

“Our beautiful black darlings are at least happy; with little labour except to the teeth, which surely, in those excellent horse-jaws of theirs, will not fail!”

Reminding the reader that such state of affairs has been purchased with considerable expenditure of blood and treasure by the British Empire, the “secular prophet” insists that if blacks are to reside there, enjoying their pumpkins, it will be an arrangement that is fair to Carlyle’s own country and people:

Fair towards Britain it will be, that Quashee give work for privilege to grow pumpkins. Not a pumpkin, Quashee, not a square yard of soil, till you agree to do the State so many days of service. Annually that soil will grow you pumpkins; but annually also, without fail, shall you, for the owner thereof, do your appointed days of labour.

In view of this concern, he asserts the following justification not necessarily for slavery but compelled servitude:

That no Black man who will not work according to what ability the gods have given him for working, has the smallest right to eat pumpkin, or to any fraction of land that will grow pumpkin, however plentiful such land may be but has an indisputable and perpetual right to be compelled, by the real proprietors of said land, to do competent work for his living. This is the everlasting duty of men, black or white, who are born into this world.

Slavery of course became a wildly inefficient means of extracting labor, a consideration revealing that slavery probably would have soon been abolished if The Civil War had been averted. Because slavery is revealed to be wildly inefficient, particularly with advances in agriculture that had been developed since the time “The Nigger Question” was published, and because multiracialism is the maddest folly for a variety of reasons, more astute and precocious readers will further question why blacks are allowed to be part of our society at all. These and other passages also have strong parallels to the propensity of large numbers of the black populace to be lifelong clients of the welfare state.

Those who foam at the mouth with cries of “racism” would be well advised that Carlyle does not limit his stern rebukes concerning idleness at “Quashee” alone. Indeed, Carlyle denounces idleness in universalist terms, including as it relates to his own white brethren:

But with what feelings can I Iook upon an over-fed White Flunky, if I know his ways? Disloyal, unheroic, this one; inhuman in his character, and his work, and his position. . ., He is the flower of nomadic servitude, proceeding by month’s warning, and free-supply-and-demand; if obedience is not in his heart, if chiefly gluttony and mutiny are in his heart, and he has to be bribed by high feeding to do the shews obedience, — what can await him, or be prayed for him, among men, except even “abolition.”

This passage, as well as concerns expressed about the potato famine in Ireland as well as a crisis in 30,000 unemployed seamstresses elsewhere in this most controversial tract could are timely as well; the United States and even world economy have been in a varying state of economic malaise over the past 25 years, with fewer numbers of generations after the boomers able to buy homes, as there has been ever diminishing economic opportunity overall.

The untouchable, scandalous essay even addresses the mad folly of importing hordes of black (and in our time, brown) laborers to meet perceived labor demands. It is this absurd “remedy” that the “Dismal Science” recommended in Carlyle’s time, as it does in modernity:

Since the demand is so pressing, and the supply so inadequate (equal in fact to nothing in some places, as appears), increase the supply; bring more Blacks into the labour-market, then will the rate fall, says [the dismal] science. Not the least surprising part of our West Indian policy is the recipe of “immigration;” of keeping down their pumpkins, and labour for their living, there are already Africans enough. If the new Africans, after labouring a little, take to pumpkins like the others, what remedy is there? To bring in new and ever new Africans, say you, till pumpkins themselves grow dear; till the country is crowded with Africans; and black men there, like the white men here, are forced by hunger to labour for their living?”

This passage reveals how precisely the same faulty, specious reasoning imploring the importation of foreigner laborers was argued in Carlyle’s own time as it is now. Perhaps most striking of all is how such advocates never think to address, in a meaningful way, the underlying causes that give rise to labor shortages. In our time, this pertains most notably to the dire ramification of succeeding waves of the feminist movement as well as increasingly brazen policies that could only be described as nakedly anti-natalist. Then and now, there is a jarring shortsightedness as to both the short and long-term ramifications of entertaining such mad folly.

This most outrageous essay is relevant in other important ways as well, including embracing natural hierarchy in human affairs while warning of the dangers of mixing do-goody, sentimental liberalism with “the dismal science” of economics and the law of supply and demand, or as Carlyle describes it “that unhappy wedlock of Philanthropic Liberalism and the Dismal Science,” as that terrible union has “engendered such all-enveloping delusions, of the moon-calf sort, and wrought huge woe for us, and for the poor civilized, in these days.” He even laments that “These Two,” namely “Exeter Hall Philanthropy” and the Dismal Science, “led by any sacred cause of Black Emancipation, or the like, to fall in love and make a wedding of it, — will give birth to unnameable abortions, wide-coiled monstrosities such the world has not seen hitherto!” Alas, if only these dire warnings were only relevant to Carlyle’s own time.

His reprimand of that “unhappy wedlock” is bolstered by the most adamant endorsement of natural hierarchy, endorsing an ideal society whereby “precisely the Wisest Man were at the top of society, and the next-wisest next, and so on till reached the Demerara Nigger (from whom downwards, through the horse, &c, there is no question hitherto. . ..” The inverse of that, a veritable dystopia, would be as follows:

Let no man in particular be put at the top; let all men be accounted equally wise and worthy, and the notion get abroad that anybody or nobody will do well enough at the top; that money (to which may be added, success in stump-oratory) is the real symbol of wisdom, and supply-and-demand the all-sufficient substitute for command and obedience among two-legged animals of the unfeathered class: accomplish all those remarkable convictions in your thinking department; and then in your practical, as is fit, decide by count of heads, the vote of a Demerara Nigger equal and no more to that of a Chancellor Bacon. . ..

Carlyle counters such egalitarianism by asserting “except by Mastership and Servantship, there is no conceivable deliverance from Tyranny and Slavery.” Quite eloquently, he articulates this maxim: “Cosmos is not Chaos, simply by this one quality, That it is governed.” Furthermore, “Where wisdom, even approximately, can contrive to govern, all is right, or is ever striving to become so; where folly is “emancipated” and gets to govern, as it soon will, all is wrong.” In Carlyle’s vision, the bane of modernity is that “the relation of master to servant, and of superior to inferior, in all stages of it, is fallen sadly out of joint.” He further warns that “by any ballot box, Jesus Christ goes just as far as Judas Iscariot.”

It should be stressed that mischaracterizations of Carlyle notwithstanding, the tract is really not a defense of slavery at all. He even expresses concern about abuses in the institution and calls for their abolition, although lamenting such reforms could take a century or more; “How to abolish the abuses of slavery, and save the precious thing in it; alas, I do not pretend that this is easy, that it can be done in a day, or a single generation, or a single century.” He also calls for that “relation to the Negros, in this thing called Slavery (with such an emphasis upon the word) be actually fair, just, and according to the facts. .. .” He even mediates his assertion with this disclaimer “You are not ‘slaves’ now; nor do I wish, if it can be avoided, to see you slaves again; but decidedly you will have to be servants to those that are born wiser than you.” As “The Carlyle-Mill ‘Negro Question Debate” confirms, “Carlyle never recommended a return to slavery as such but rather a return to something akin to European-style serfdom.”

In many ways, even Carlyle, despite all the protestations and condemnations of “racism,” is too optimistic on these questions of race. For those of more conventional sensibilities, the following quote doubtlessly smacks of the sort of (supposedly) insidious genteel “racism” that might be used as a caricature of a certain sort of Southern segregationist. Not withstanding the sort of frothing at the mouth and pearl-clutching it assuredly induces in many, it nonetheless reveals that Carlyle regards “Quashee” with some vestige of humanity, irrespective of other demeaning remarks:

Do I, then, hate the Negro? No; except when the soul is killed out him, I decidedly like poor Quashee; and find him a pretty kind of man. With a pennyworth of oil, you can make a handsome glossy thing of Quashee, when the soul is not killed in him! A swift, supple fellow; a merry-hearted, grinning, dancing, singing, affectionate kind of creature, with a great deal of melody and amenability in his composition. This certainly is a notable fact: The black African, alone of wild men, can live among civilized men. While all manner of Caribs and others pine into annihilation in presence of the pale face, he contrives to continue, does not die of sullen irreconcilable rage, of rum, of brutish laziness and darkness, and fated incompatibility with his new place; but lives and multiplies, and evidently means to abide among us, if we can find the right regulation for it.

A survey over the past 60 years or more (or for that matter, a survey of all humanihistory as it relates to Africans) does not lend itself to sharing Carlyle’s optimism on such matters. Indeed, the conditional statements that govern this passage are most noteworthy and require the strongest emphasis possible. He premises such assurances with qualifiers like “except when the soul is killed out of him” and “when the soul is not killed in him.” The final sentence concerning the intention to “abide among” is predicated on the conditional statement “if we can find the right regulation for it.”

All experience and a hard, unflinching look at the realities of race lead to the conclusion that no such “regulation” is possible, at least not on the whole, on an aggregate, collective level.2 As has been stated elsewhere, a concise litany summarizing this multiracial experiment can be summarized as follows. Blacks not only harbor collective, racial resentment against whites, they harbor what is more precisely described as an ancient hatred. That ancient hatred grows more perilous as whites continue to abolish themselves, relinquishing political power and majority status not just in the Anglosphere in the New World but in that sacred continent of Europe as well. This is compounded by indelible, persistent differences in intelligence that average between one and two standard deviations, but in practice vary even beyond that, with three standard deviations or more likely in many scenarios: consider white individuals with an I.Q. of 130 interacting with a black or other person with an I.Q. even lower than 85. These problems persist despite many trillions wasted on great society and welfare programs, the establishment of onerous government entities like the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, so on and so forth. Such problems are further compounded by the problems inherent with multiracial societies more generally, and that all peoples, but especially European peoples, have a right to common race, blood, and soil that is foundational to a cohesive society and civilization.

Particularly given the contemporary controversies surrounding Haiti, from the gruesome, unspeakable horrors that continue to plague that island, to controversies stemming from their unwanted infusion in communities like Springfield, Ohio, it is of particular interest that Carlyle expressly warns of the dangers of Haiti in warning against the sort of pathological altruism that was gaining favor in his day. Carlyle’s dire warning reads as follows:

Or, alas, let him look across to Haiti, and trace a far sterner prophecy! Let him, by his ugliness, idleness, rebellion, banish all White men from the West Indies, and make it all one Haiti,-with little or no sugar growing, black Peter exterminating black Paul, and where a garden of the Hesperides might be, nothing but a tropical dog-kennel and pestiferous jungle, — does he think that will for continue pleasant to gods and men?

Carlyle foretells further:

I see men… land one day on those black coasts men sent by the Laws of this Universe, and inexorable Course of Things; men hungry for gold, remorseless, fierce as old Buccaneers were:, — and a doom for Quashee which I had rather not contemplate!

Such a vision portends a myriad of horrors, past, present, and even future, from Haiti itself, to Somalia and a seemingly inexhaustible number of killing fields in Africa, to the aforementioned prospect of Chinese or Muslim hegemony in concert with the Great Replacement and the further disenfranchisement of European peoples. These allusions about Haiti of course failed to predict how such folly would harm European peoples, as has occurred in the American experience with the multiracial experiment and above all the horrors recounted in Rhodesia and post-apartheid South Africa. Such considerations would, without a doubt, disabuse even Carlyle of his delusions about the races “abiding together…if… a right regulation for it” can be achieved.

The writings of Thomas Carlyle stand as both a warning and revolt against modernity, which is precisely why he has lost favor in English Departments, academia writ large, and other cultural centers of power. Sartor Resartus and On Heroes and Hero Worship remain his most important and accessible works: truly indispensable reading, notwithstanding marginal status in the modern world, floating in and out of print. “Shooting Niagara, and After?” is an outrageous affront to received orthodoxies about the sanctity of democracy as an end to itself. Given the current state of hysteria surrounding that one particular epithet, “On the Nigger Question” exceeds “Shooting Niagara” in audacity by orders of magnitude. But as this critique sets forth, despite however outrageous and offensive it is to many, both in Carlyle’s own time and in our own, this most controversial essay raises so many of those hard, difficult questions that faced his contemporaries as well as the modern world and so many of its vices, dysfunctions, and terrors that he, among others, warned against. Great tracts, even political tracts addressing political issues of the time, discuss not just those political controversies, but conceptualize these issues as they relate to broader, more abstract concepts and principles. A tract that advocates a pro-life position on abortion will tether the position it advocates to broader, more universal considerations such as the value of life or how civilizations cannot endure with anti-natalist policies. A tract advocating for the right of euthanasia for the terminally ill will anchor its position with foundational precepts extolling the value of quality of life. As with his other works, Carlyle centers his attacks on controversies of his time (and as it turns out, our times as well) on other more universal principles, including, sadly, very grave, weighty matters that still afflict Western civilization and the United States most particularly. Moreover, as the Shiloh Hendrix escapade has demonstrated, embracing this essay, regardless of how outlandish, offensive, or taboo it may seem to received orthodoxies, takes initiative from the left, and prevents our ideological enemies from setting the terms of discourse and rules of engagement. For these and other reasons, “On the Nigger Question” remains an important and timely work by the Sage of Chelsea, and it would be a mistake to continue to shy away from it any further.

PLEASE NOTE: the eventual success or failure of this endeavor depends in large part on reader support and collaboration. Readers who enjoy this content are urged to consider offering a paid or founding member subscription in consideration of the time and labor expended to write and publish these texts. Readers who enjoy this essay are also asked to press the “like emoji” to signify their favor.

Follow Richard Parker on twitter (or X if one prefers) under the handle (@)astheravencalls. Delete the parentheses, which were added to prevent interference with Substack’s own internal handle system.e.

1 The assertions concerning prodigious pumpkin consumption by indolent freed slaves is a peculiar one absent further context. One would suspect they must have eaten something besides just pumpkin, but that is not related in the text. Thankfully, a web article “The Carlyle-Mill ‘Negro Question Debate” provides critical historical background concerning the states of affairs in the West Indies that had arisen after “the end of the apprenticeship and immediate liberation” in 1838, which was agreed to in exchange for trade “protection [vis-à-vis] of a hefty preferential sugar tariff:”

In 1839, Exeter Hall, the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society (BFASS) was formed, this time with an international mandate. . . . Specifically, BFASS-associated missions were critical in blowing the whistle on attempts by plantation-owners to re-impose dependency on their ex-slaves with arbitrary local laws, high rents, extortionary debt and occasional burnings of black settlements that were “too distant” from the plantations. When the legal system failed to help, the BFASS began raising large amounts of money to help ex-slaves re-establish themselves in “free villages” away from the vicinity of the plantations and the economic and political domination of plantation-owners.

The termination of the “apprenticeship” and the BFASS resettlement loans led to a mass exodus of ex-slaves out of the plantations and into their own small farms in the hills of Jamaica and other West Indian islands (the “pumpkin farms” Carlyle decries). This created a large and sudden labor shortage, which led to considerable economic difficulties for the sugar plantations. This was only modestly counterbalanced by a step-up in the importation of Indian “coolie” labor and European indentured servants.

Great article. I’d heard the name Carlyle, but never read anything by him.

Interesting that some had more sympathy for Negroes than they had for the often starving native Brits and Irish.

Shouldn’t US whites whose ancestors suffered on either side in the Civil War be paid compensation by the descendants of black slaves still living in the US?

Fair is fair.

One disagreement:

“Europe” is “floating rapidly, . . .nearing the Niagara Falls.” Alas, it seems she already has long since gone over Niagara and is not likely to survive.

Unduly pessimistic, although if trends continue it will become true.

It took the Spanish several centuries to do the Reconquista, but with airplanes and other modern technology we can do it in a year or so. Many citizens are doing their bit to encourage remigration, and some of our dark skinned guests are taking the hint, but to see big numbers we need the governments involved.

An important point in this essay is that the Negro unlike other forest peoples never leaves us alone and wants to mix in with white people. It was penned before blacks had better education and the bell curve was understood.

Wasn’t the phrase “telescopic philanthropy” coined by Dickens in Bleak House? That novel was serialized in 1852-53, so the expression must have been fresh in the public mind when Carlyle published the revised version of his essay.

Indeed it was. I hope my writing was not interpreted to suggest Carlyle uses that phrase in this essay. He does not as far as I recall. The cartoon in question has been referenced in various discussions of this essay and the controversies that arose after The Abolition Act, including supposed abuse of the “apprencticeship” loophole that allowed slave holders to continue indentured servittude after the act, and the crisis with spoliing cash crops in the wake of the pumpkin crisis, and more particularly to get freed slaves to work on these plantations so that such colonial possesions do not go to waste.

I will add that I am honored you have read this and potentially other essays. I hope you will take a gander at The Raven’s Call: A Reactionary Perspective. (theravenscallsubstack.com).

The world’s leading expert on African brains, Dr. Michael Woodley of Menie, is back in public after five years of hiding. He did a YouTube interview two months ago: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Y1J-YZn50Q

There is something seriously wrong with him. He seems to have experienced severe emotional and cognitive trauma. He lost his ability to publicly speak well, and he seems very neurotic. And, why is he questioning Spearman’s hypothesis? He says in the interview that he has just completed research showing that when he studied Europeans and Africans in prison, the increasing g-loading of IQ tests no longer positively correlated to the magnitude of the IQ differences between these incarcerated Europeans and Africans. Is his research faulty? My mathematical/quantitative IQ is too low to understand the mathematics.

Here is the full Woodley of Menie interview: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mNEdYeCI-Wg

I don’t know why DuckDuckGo gave me some one minute cut of the interview.

Woodley and Dutton are both a little bit “odd” – unlike predecessors like Murray, Eysenck, Lynn, Cattell, etc.

Fabulous..riveting..illuminating and sad commentary on how far the..West..thanks to sclerotic..hideous multi-culty..trendy..schizoid JEWISH POWER.. has fallen…**