Quantum Dylan: A Double Act, Part 2

It is doubtful whether Dylan has ever read Wagner’s Judaism in Music — in which it is argued that Jewish musicians are essentially bricoleurs, only capable of “nonsensical gurgling, yodeling and cackling.” Nevertheless, Dylan’s gloriously imperfect and constantly mobile singing voice, and his boundless ability to mix musical styles, eerily correspond to Wagner’s stereotype of ‘the Jew’ as aesthetically and culturally impure.”[1] Dylan’s music is, in Murphy’s words, “littered with tiny rippling echoes of this giant national storehouse of folk ballads, hymns, Civil War songs, country folk blues, urban electric blues, country and western, bluegrass, dust-bowl folk, tin-pan alley, Broadway, gospel, jazz-beat, crooning, Tex-Mex, big band, rhythm and blues, pop music, reggae, rap — and all the rest.”[2]

Dylan freely appropriates other people’s melodies, chord changes, rhythm patterns, and tonal and textual phrases. These pepper his works. … [Dylan] adopts musical masks, styles, and personas. He is a great mimic. But he is also unmistakably Mr. Dylan whatever he does.[3]

The radical hybridity of Dylan’s music and lyrics has a family resemblance with his “comrade-in-arms” Jimi Hendrix who rationalized his ambivalence towards both Blackness and America through the nomadic ideology of the gypsy – a symbol of his mixed racial and ethnic heritage:

In Dylan, Hendrix recognized a kindred traveler, another musical itinerant who rationalized his own ambivalent identity through music. … Hendrix and Dylan — gypsy and hobo — navigated a musical passage of self-invention that led them into borderlands where musical styles, idioms, and traditions overlap.[4]

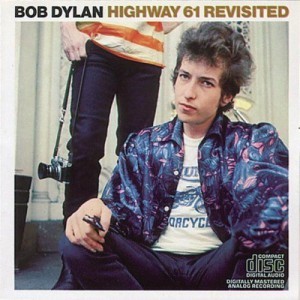

Race and Ethnicity on Highway 61

Highway 61, which is used in Dylan’s album title and in the title of a song on the album, runs north from New Orleans to Dylan’s home state of Minnesota. It is known as the Blues Highway — the route out of the South taken by large numbers of African Americans on their way to Chicago. Stratton describes “Like a Rolling Stone” and the whole of Highway 61 Revisited as “Jewish blues”:

Highway 61, which is used in Dylan’s album title and in the title of a song on the album, runs north from New Orleans to Dylan’s home state of Minnesota. It is known as the Blues Highway — the route out of the South taken by large numbers of African Americans on their way to Chicago. Stratton describes “Like a Rolling Stone” and the whole of Highway 61 Revisited as “Jewish blues”:

The particularly Jewish feeling of disillusion and the loss of a moral compass pervades the album. … ‘Highway 61 Revisited’, the song whose title returns us to the Blues Highway, begins with a verse about God’s testing of Abraham in Genesis, in the Torah, the Jewish part of the Bible. … In the biblical narrative, God orders Abraham to sacrifice Isaac. When it is clear that Abraham will perform this deed, an angel stays Abraham’s knife-hand. Jewish interpretations of this story have mostly understood God’s instruction as a way of testing Abraham’s faith and loyalty. In Dylan’s retelling, there is no reprieve. God commands Abraham to kill his son, and threatens retribution if the deed is not carried out. We need to note the semantic shift here. Dylan’s God does not ask for a sacrifice; he asks for a murder, a killing. When Abraham queries where the killing should be done, God tells him on Highway 61. The resonance here, again, is the Holocaust, often considered to be the most overwhelming test of Jewish faith. Indeed, like the victims of the gas chambers, in the Genesis narrative Isaac was to be burnt. Holocaust, with its meaning of ‘a burnt offering’, is a term used to translate Isaac’s query to his father about where the lamb was for the sacrifice as well as to describe the Nazi genocide. In Dylan’s placing of the sacrifice on Highway 61, listeners bring the blues understanding to the Jewish experience.[5]

Al Kooper comments in his Britannica article that Dylan’s image anno 1968 had changed: “with shorter hair, spectacles, and a neglected beard, he resembled a rabbinical student.” In a 1968 interview with Toby Thompson, Dylan’s mother emphasized that “there’s a huge Bible open on a stand in the middle of his study. Of all the books that crowd his house … that Bible gets the most attention. He’s continually getting up and going over to refer to something.”[6] Doubtless, Dylan’s identification with Judaism is complex and ambiguous. Meisel claims that the idea of the Christian Dylan was already in place at Newport in 1965, well before Dylan’s actual conversion to Christianity in 1979.[7] Stephen J. Whitfield, however, emphasizes Dylan’s Jewish (transgressive?) identities:

Formally satisfying rabbinic rules of inclusion, remaining a Jew in the halakhic sense, he has been ecumenical — sometimes expressing in lyrics and interviews attitudes that cannot be considered Jewish, sometimes offering tantalizing affirmations of that very identity. He has shattered the difference between the Jew and the Other as though the historic boundary between them had never existed, and thus leaves dangling, fragile and unstable, what the historian of Jewish identity might well despair of resolving.

On the surface, “Like a Rolling Stone” (1965) is a song written as an attack on a woman by whom Dylan felt betrayed. According to Stratton, however, “the song was triggered by Dylan’s emotional reaction to the Jewish disillusion with the promises of White American society coupled with the growing cultural awareness of what was coming to be known as the Holocaust.”[8] Whitfield writes that Dylan celebrated his son Jesse’s bar mitzvah in Jerusalem and vaguely affiliated for a while with the Lubavitcher Hasidim (a racialist sect with attitudes of being qualitatively different from non-Jews). Whitfield continues to remark that the Infidels album (1983) offered something unexpected:

‘Neighborhood Bully’ constitutes a capsule history of the Jewish people itself. Spitting out the song rapidly, in a tone of ironic bitterness, he blended a millennial history of unjust persecution with an unnuanced defense of a beleaguered Israel. It could have been a Likud campaign song.

Dylan as countercultural Trickster

Dylan as countercultural Trickster

Murphy (p. 57) quotes Dylan, saying that “Truth was the last thing on my mind, and even if there was such a thing, I didn’t want it in my house.” Hence, deception, deceit, misidentification — “the losing and finding, reversing and inverting, hiding and confusing, masking and revealing of identity” — are essential to any Dylanological analysis.

Bob Dylan is always what he is not. Conversely, if not perversely, he is also always not what he is. He is a great impersonator — always two people at one time, a double act. An endlessly deliciously wickedly bifurcated identity is the nature of a great comic character — and a niggling intuition of that … also raised the ire of his Newport audience. Yes he was a protest singer, but a singer of comic protest songs. ‘Maggie’s Farm’ is a classic of the type. Such songs can have a very serious edge. But they are not serious in an earnest, faux-tragic way. They are not solemn or serious in that thin-skinned, moralizing, pompous way that invites, indeed positively demands, satire. Satire is where Dylan began. His first compositions were topical songs laced with aw-shucks humor and surreal wit — low absurdity essentially. Then he gradually upped the ante, moving into ever-more sophisticated terrain.[9]

What is achieved in Dylan’s case is “comic chaos” — a “quantum effect” — by making “affirmations and denials in the same breath”. Hence, Murphy’s description of Dylan’s music as “comically quantum”:

The greatest of his songs are peppered with quantum tonal effects — tones that are one thing and another at the same time. Bob Dylan will tell you that his songs are simple, but of course he is an aw-shucks kidder. In fact, his songs masterfully exploit the resources of tonic-dominant harmony — with their endless modulations, shifts back and forth, between keys and major and minor triads. He also often mischievously undermines the tonic in favor of tonal ambiguity. He’ll oscillate harmony between the tonic and the subdominant, or start (say) a stanza with the submediant rather than the tonic, or engineer inconclusive cadences because he approaches them indirectly (say by way of the subdominant of the subdominant). Harmonic modulation and various kinds of harmonic equivocation lend his music its characteristic spooky timeless mythic quality. Dylan also utilizes the quantum resource of indeterminate pitch. He will often deploy tonal wobbles — notes that equivocate — by fusing the sharpened notes of the tempered scale with the flatter notes of pre-Renaissance or non-European modal scales — creating false relations. This is the musical version of talking out of both sides of your mouth — little quantum leaps in which shaper and flatter versions of the same notes coexist in the same music space or at least their coexistence is implied.[10]

Murphy points out the ambidextrousness of comic truth: ”It is a truth that is a lie at the same time.”[11] Dylan’s music — filled with truth as contradiction — fits into the cultural logic of complementarity:

This ambidextrousness applies to all aspects of his music — tonal, lyrical, instrumental, and vocal. Vocally, he half sings, half talks. Oftentimes this approximates something that is neither speech nor singing strictly speaking but rather a mordant creaky growl — a rasping, scratching hoarse vocal rumble. … And it is not just the timbre of the voice that makes us sit up and pay attention. It is also the phrasing — the odd emphases that Dylan gives to words or syllables — emphases placed where you’d least expect them. And then there is the way he elongates vowels — stretching conventional short sounds into long elastic unexpected elocutions. ‘What you would least expect’ is the comic desideratum. The comic mode is built on exquisite sharp-edged double coding. Arthur Koestler [The Act of Creation] called it bi-sociation. Kenneth Burke [On Symbols and Society] called it incongruity. No matter what it is called, Dylan does it effortlessly. A long time ago — in the nineteen-sixties — when, with witty aforethought, he announced ‘I embrace chaos’, Dylan was not declaring his love for social transgression or political anarchy but rather for comic pandemonium.[12]

Murphy, thus, portrays Dylan as “the quintessential joker man” with an “ear for witty musical quotation” — “a musical chameleon, an evasive, shape-shifting, identity-changing, metamorphosing character.” His lyrical imagination is filled with “dark paradox and witty contrast”. Despite its leftist connotations, Dylan’s music — like Seinfeld’s sitcoms — essentially communicates an ethic of political apathy. Dylan qua comic artist is an impostor who, of necessity, despises engagement: “Comedy is a function of distance — of seeing things one step removed.”[13] Like a comic artist, Dylan plays with the expectations of the audience – “who loves him as much as he despises them … and who can love him only because they misunderstand him”[14] – causing pandemonium, “as smug, senile and simpering judgments are turned upside down.”[15]

Concluding Remarks

In summary, Dylan is part and parcel of the culture of critique that has come to dominate academic discourse and the arts: Undermining traditional certainties by promoting indeterminacy, irrationality, ambivalence, identity bricolage and relativism.

Dylan’s case is a reminder of the multiple affinities between early 20th-century avant-garde movements and “postmodern” developments. Schoenberg’s radical disciple John Cage (1912–1992) employed the principle of complementarity in his rejection of the classical form based upon rational relationships among ordered tones. Cage saw music in the juxtaposition of noise/sound and silence, i.e. (as in Bohr’s complementarity and Ionesco’s anti-logic) as a contrast of “hitherto irreconcilable elements result[ing] in the undermining of the very heart of traditional ‘logical’ epistemology, the subject-object dichotomy.”[16] Christopher Lasch suggests that Cage puts forward a musical aesthetic in which musical sounds “are experienced as equivalent to any other kind of sound”.[17]

Lemert (p. 67) notes that this style of thought can be seen in many 20th-century intellectual and artistic movements, avant-garde ideas and cults: relativity theory, complementarity and Heisenbergian indeterminacy, absurdism, surrealism, expressionism, Cubism, Dadaism, atonalism and experimentalism. Lawrence Wilde, with reference to the parallels with expressionism, claims that Dylan in the early 1960s succeeded in fulfilling Adorno’s task of negating the values of the existing society. Dylan, as the original expressionists, “creates a novel relationship between content and structure in order to jolt the recipient towards an emotional confrontation with prevailing conservative values.”

Furthermore, Dylan’s Jewish middle-class discontents bear resemblance to the Cabaret Voltaire of the Dada movement, starring Marcel Janco and Tristan Tzara, who — through their notoriously rebellious gestures — “sought to deconstruct the conformist mentality that celebrated war and upheld bellicose nationalism.”[18] The chaotic and cacophonous atmosphere of the Cabaret Voltaire was purposefully cultivated by the Dadaists, who “celebrated the irrational, invited irony and rejected all logic in order to attack the warmongering power structures and their so-called ‘rational’ cultural codes.”[19]

Similarly, in “Ballad of a Thin Man” and “Desolation Row” on Highway 61 Revisited, for example, Dylan employs “a complete reversal of the roles of the respectable and the damned. In these songs the underworld of the rebels and freaks is the liberated, sane place to be, and the world of the conservatives is shriveled, hypocritical and in decay.” “Desolation Row” presents a “decentering” vision, reversing the normal relationship between center and periphery, between mainstream and alternative worlds.

Iain Ellis (p. 14) points out that the subversive wit of art movements like surrealism, dada, pop art, and situationism is indelibly imprinted on the work of rock humorists like Dylan. In the style of “superiority” humor, he used humor as a countercultural weapon for social change. Superiority humor tends to elevate the appearance or the actions of one individual or group over those of another and generate amusement at the misfortunes of others.[20] Bernard Saper lists 6 generalized types of specifically Jewish humor,[21] the first of which seems to be a pertinent description of Dylan’s superiority humor: “Assuming superiority, particularly in intelligence, wisdom, and virtue; besting of bigots and adversaries; psychologically beating the (alleged) out-group persecutors at their own game.“

Dylan’s “comic militancy” and deconstructionist qualities apparently bear a “family resemblance” to cultural critics like Karl Kraus in the center of Vienna’s “satiric vortex”, or, in another context, Franz Boas smuggling irony into scientific discourse. Kraus asserted that the trivial contains apocalyptic implications, and devoted many pages to moralistic discourses on minute matters of grammar and syntax.[22] Boas’s writing, taken as a whole, “has a kind of abusive perversity”, according to Arnold Krupat; he was engaged in “a kind of abysmal ironic vision”, showing “a real delight in his ability to expose or deconstruct … generalizations that could not stand up to his aggressive ironic scepticism.”[23]

Significantly, Dylan conflates speech and song (in a 1965 interview he claimed that “There would be no music without the words”). Schoenberg, likewise, devised a style of vocal recitation called Sprechstimme, designed to be neither speech nor song but some hybrid of the two. Similarly, Wittgenstein (in Philosophical Investigations) stressed the musical aspects of normal speech, emphasizing that speech is a special case of music, i.e. both speech and music are games with sounds. Likewise, Ernst Bloch (in Geist der Utopie, 1918), who mixed music, religion and Marxism “into a heady brew of revolutionary romanticism”,[24] transforming music into words (word-music). Despite the lack of evidence for any direct genealogies, Otto Weininger’s dictum that Jewishness (Judentum) is a tendency of the mind is starting to look intriguing.

Piero Scaruffi (pp. 33, 69), judges Dylan as the single most influential musician of the 1960s, turning music into a form of mass communication. Unsurprisingly, his legacy, his brand of targeted social satire, can be traced “in all subsequent protest youth cultures, whether in the hippie and punk movements, or even segments of hip-hop culture.”[25] There is, for example, a striking continuum extending into the hard rock-influenced rap music of the Jewish trio Beastie Boys (a hip-hop/rock group consisting of Michael Diamond, Adam Yauch and Adam Horovitz), the first non-African-American rap group to popularize rap for a White audience, releasing their first album in 1986. The Beastie Boys started out as a post-punk hardcore band (a White-coded genre) cooperating with possibly the only contemporary African-American hardcore band, Bad Brains.[26] They signed with Def Jam, whose co-founder Rick Rubin produced their debut album, Lincensed to Ill.

Once again, we have an example of Black-Jewish fusion within the Black-White binary — a ‘black-face’ imitation of a New York African-American accent (i.e. street slang). Once again, we have a musical style with chanted (“rapped”) rhythmic/rhyming speech. Stratton compares a track on Licensed to Ill, ‘Paul Revere’, with Dylan’s “talking blues” in ‘Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream’ and ‘Maggie’s Farm’ (released on Bringing It All Back Home, 1965) — “perhaps the closest Dylan came to precursing rap.”[27]

Dylan personifies the process of post-World War II Jewish Whitening in a time when American Jews were discursively and culturally constructed as White. In this process, Jews were also considered to have qualities that placed them outside of Whiteness. Hence, the description of Jews as a boundary case — both insiders and outsiders,[28] and Billig’s evaluation of Dylan as “an outsider posing as a dispossessed insider”.[29]

As a comic artist — whose comic mode is built on sharp-edged double coding — he is a tease who “openly debunks and hounds the audience.”[30] His (predominantly die-hard leftist) Ur-audience, who loves him as much as he despises them, can help to explain the Dylan enigma through the following no-nonsense description:

This audience has all the comic intellectual vices — pomposity, obsession, zeal, and so on. As the picaro moves on down the road, you can see him vicariously hitting these numskulls around the head — telling them: don’t think twice, it’s alright, but you’ve wasted my precious time. Occasionally they yelp in complaint — yet they come back for more, because he is their hero — and they really do not understand who he is. They are clueless.[31]

References

Albright, Daniel. Music Speaks: On the Language of Opera, Dance, and Song. Rochester (NY) & Woodbridge (UK): University of Rochester Press, 2009

Bryan Cheyette, ”On the ’D’ Train: Bob Dylan’s Conversions,” in Corcoran, Neil (ed.). Do You, Mr. Jones? Bob Dylan with the Poets and Professors. London: Chatto & Windus, 2002

Clarke, John R. Looking at Laughter: Humor, Power, and Transgression in Roman Visual Culture, 100 B.C. – A.D. 250. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 2007

Dettmar, Kevin J. H. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Bob Dylan. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009

Ellis, Iain. Rebels Wit Attitude: Subversive Rock Humorists. Washington, DC: Soft Skull Press, 2008

Holt, D. & Douglas Cameron. Cultural Strategy: Using Innovative Ideologies to Build Breakthrough Brands. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 2010

Knight, Charles A. The Literature of Satire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004

Krupat, Arnold. Ethnocriticism: Ethnography, History, Literature. Berkeley, Los Angeles, Oxford: University of California Press, 1992

Lemert, Charles. Durkheim’s Ghosts: Cultural Logics and Social Things. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006

Meisel, Perry. Blackwell Manifestos: Myth of Popular Culture: From Dante to Dylan.

Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009

Murphy, Peter & Eduardo De La Fuente (eds.). Philosophical and Cultural Theories of Music. Vol. 8. Leiden & Boston: Brill, 2010

Oring, Elliott. The Jokes of Sigmund Freud: A Study in Humor and Jewish Identity. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1984

Oring, Elliott. Jokes and their Relations. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1992

Papanikolas, Theresa. Anarchism and the Advent of Paris Dada: Art and Criticism, 1914 — 1924. Farnham & Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2010

Scott, Derek B. Musical Style and Social Meaning: Selected Essays. Farnham & Burlington: Ashgate, 2010

Slobin, Mark (ed). American Klezmer: Its Roots and Offshoots. Ewing, NJ: University of California Press, 2001.

Stratton, Jon. Jews, Race and Popular Music. Farnham & Burlington: Ashgate, 2009

Whitfield, Stephen J. “Enigmas of Modern Jewish Identity”; Jewish Social Studies, Vol. 8, No 2/3, Winter/Spring 2002, pp. 162 — 167

Zak, Albin J. III, “Bob Dylan and Jimi Hendrix: Juxtaposition and Transformation ‘All along the Watchtower’”, in Journal of the American Musicological Society, Vol. 57, No. 3 (Fall 2004), pp. 599 — 644

http://campus.queens.edu/depts/english/dylan_goes_electric_the_newport_.htm

http://perrymeisel.blogspot.com/

[1] Bryan Cheyette, ”On the ’D’ Train: Bob Dylan’s Conversions,” in Corcoran 2002, 225

[2] Peter Murphy in Murphy & De La Fuente 2010, 52 — 53

[3] Murphy, 54 — 55

[4] Zak, 637 — 638

[5] Stratton 2009, 100 — 101

[6] in Zak 2004, 622

[7] Meisel 2009, 159

[8] Stratton 2009, 98 — 99

[9] Murphy in Murphy & De La Fuente 2010, 61

[10] Murphy, 63

[11] Murphy, 58

[12] Murphy, 59

[13] Murphy, 62

[14] Murphy, 51

[15] Murphy, 60

[16] Lemert 2009, 69

[17] cited in Murphy & De La Fuente, p. 100

[18] Papanikolas 2010, 4 — 5

[19] Papanikolas 2010, 84

[20] Clarke 2007, 4

[21] Bernard Saper, “Since when is Jewish Humor not Anti-Semitic?” , Semites and Stereotypes, pp. 83 — 84

[22] Knight, Charles A. The Literature of Satire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, 259

[23] Krupat, Arnold. Ethnocriticism: Ethnography, History, Literature. Berkeley, Los Angeles, Oxford: University of California Press, 1992, 89 – 99

[24] David Roberts, ”Music and Religion: Reflections on Cultural Secularization”; De La Fuente & Murphy 2010, 80 – 83

[25] Ellis 2008, 74

[26] Stratton 2009, 105 – 108. Stratton cites Rick Rubin’s co-founder of Def Jam, African-American Russell Simmons: ”I mean, when I grew up I was bussed to a Jewish school and I didn’t know why the WASPs … would chase me into this one particular area of projects … and I didn’t know why this one group of White people were chasing me and this other group were protecting me. But it was because I was a Jewish co-op. (laughter). So I have a relationship with them.”

[27] 2009, 125

[28] Stratton 2009, 110, see also Biale, Galchinsky and Heschel, ‘Introduction: The Dialectic of Jewish Enlightenment’, in Biale, Galchinsky and Heschel (eds), Insider/Outsider: American Jews and Multiculturalism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), p.5

[29] cited in Stratton 2009, 126

[30] Murphy & De La Fuente, p. 50

[31] ibid, p. 51

Comments are closed.