American White Awareness during World War II

World War II is often referred to as the war against racism, as if it were fought to prevent future racial discrimination. This is far from the truth. In fact there are numerous accounts which show explicit White consciousness. This piece does not pretend to give a complete picture, but rather points out some illustrative examples.

Pearl Harbor and war in the Pacific

The editorial of Life magazine in May 1945 included the following remarks: “Americans had to learn to hate Germans, but hating Japs comes natural—as natural as fighting Indian wars once was.” This is in a nutshell is the difference between the average American attitudes towards the enemy during World War II: the Japanese were a different race. Besides this, the Americans felt treacherously attacked by Japan in Pearl Harbor, but they did not feel any need for revenge or hatred against the Germans. In the government propaganda the emphasize in the war against Germany was placed on the National Socialist (commonly referred as Nazi) regime rather than the Germans, preventing the feeling among second-generation German-Americans that they were fighting their own kind.

Another distinctive difference between the approach towards Japanese-Americans and German-Americans was that the distrust against the former was much greater than against the latter. All 120,000 Japanese-Americans were rounded up in the beginning of 1942 and detained in concentration camps in the most remote and inhospitable places of America. They were not drafted (although there existed small volunteer units), nor were they deployed as laborers in the war-industry. On the other hand, there was no official distrust of any kind towards Americans originating from European Axis countries which were drafted and employed in the war industry without restrictions.

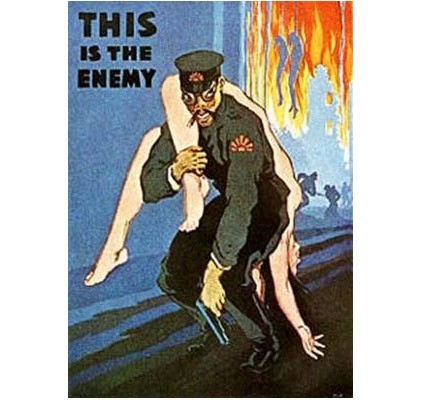

The Americans were very negative towards Japanese who were labeled as aggressive, savage, brutal and treacherous. They were even considered as a subhuman menace. War commentator Ernie Pyle described it by stating that “the Japanese were looked upon as something subhuman and repulsive; the way some people feel about cockroaches or mice.” Historian Allen Nevins explicitly touched the race factor: “Probably in all our history no foe has been so detested as were the Japanese. Emotions forgotten since our most savage Indian wars were reawakened.” When the government did a questionnaire among the American population about the proper fate of the Japanese, roughly one out of eight replied they should be exterminated. This option was not included in a similar questionnaire on the fate of the German people (although U.S. Secretary of State Henry Morganthau, Jr. certainly would have wanted it).

Race relations in the American army

The American army was completely segregated at the beginning of the war. It was not until well after the war that the U.S. Armed Forces were slowly desegregated by Executive Order 9981 of President Truman in July 1948. The segregation not only meant separate units, but also distinctive duties. Frontline duty was preserved for Whites, while Blacks were delegated to labour units and performed supply tasks, which gave them the name of ‘cantine commando’s’ among the frontline troops. As the war progressed American losses mounted and late in the war Black frontline units were grudgingly created to compensate for White manpower shortages in the frontline. Even when deployed as fighting troops, Blacks were preferably assigned to supportive branches, like the artillery.

The creation of Black frontline units did not mean that they were always deployed accordingly. The all-Black 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion was a daring experiment at the time, because parachute troops had élite status (together with Rangers and Marines) and was accordingly a bulwark of Whites. When the Black battalion was offered to the commanders in Western Europe they replied that “simply had no use” for it despite the horrific losses among American parachute troops as a result of extensive use in the Italian and French campaign of 1943/1944, not to speak of the setbacks at Arnhem and bearing the brunt of the German Ardennes-offensive (Bastogne). Ultimately they were wasted fighting forest fires in Oregon as a result of Japanese balloon attacks with incendiary bombs. Another larger Black unit, the 93th Division, was only assigned to guard duty in the Pacific.

In the end Blacks never made up more than 10% of the armed forces and more than 90% of the Blacks were assigned to physical labour behind the frontline. One of the reasons for the lukewarm reception of Blacks in the army was the low test results of Blacks on the Army General Classification Test (AGCT). Only 8.5% of all White recruits ended up in the lowest level V compared to 49.2% of all Black recruits. When we take into account the three highest levels (I, II and III), the gap between White and Black is even bigger: 66.7% to 16.1%. It meant that the great majority of Blacks (83.9%) scored at the two lowest levels, while the majority of Whites (66.7%) scored in the highest three levels. These results were backed up by the experience in both World Wars of underperforming Black units, like the 92nd Division. During the Italian campaign this division was repeatly pushed back by inferior Axis forces, even by the puny Italian troops during the battle of Garfagnana in December 1944.

Colonial troops and the liberation of Paris, August 25, 1944

Colonial possessions proved a valuable—if not vital—supply of manpower for the British and French armies. The British-Indian forces alone comprised over 2.5 million men, making up roughly half of the forces under British command. In the Free French forces under De Gaulle Whites did not make up more than one third of all forces, as they were mostly comprised of Arabs and Blacks. The French forces were basically composed of mercenaries and their troops acted as such when they advanced in Italy, leaving a trail of rape, killing, pillage and plunder locally known as the Marocchinate. When Rome was taken by the Americans, the French colonial troops were not allowed in the city by order of general Mark Clark on request of Pope Pius XII, who was well informed and was appalled by what he had heard about the atrocities in the Italian countryside.

The only Free French unit who participated in the Normandy campaign that led to the liberation of Paris was the French 2nd Armoured Division, which was anything but French. It was a unit made up of Blacks, Arabs, French sailors and even Spanish communists, who were interned in France after the Spanish civil war and joined the Free French forces in 1940 rather than remain in occupied France. Only 25% of the division was made up of native French. This issue was addressed by Eisenhower’s Chief of Staff Walter Bedell Smith in January 1944 before the invasion of France: “It is more desirable that the division mentioned above consist of white personnel.”

Even when all other French divisions were stripped of their White personnel there were not enough Whites to make the division 100% White, which was an American precondition for allowing the French to liberate Paris. Even Eisenhower’s deputy Chief of Staff, the British general Frederick Morgan, was pressing for an all-White French division for the liberation of Paris: “I have told Colonel de Chevene that his chances of getting what he wants will be vastly improved if he can produce a White infantry division.” In the end there was a silent compromise among the Allies in which all Blacks were removed from the French 2nd Armoured Division and Meditterenean troops (Syrians, Algerians, etc.) were added to make the division look more White.

Comments are closed.