Jewish Partisan Warfare During WWII

The recurring theme of Jewish suffering during World War II in 1990s movies (Schindler’s List) has gradually shifted to the image of the outsmarting Jew (The Counterfeiters, 2008) and even the resisting Jew (Defiance, 2008). This shift of focus has not been to the benefit of the image of the Jewish victim, because it exposes Jewish crimes as well. The main character in The Counterfeiters is a petty criminal who is willing to work for the German war effort, but the movie “Defiance” has opened up the historical Pandora’s box of Jewish partisan violence and collaboration with the Soviets.

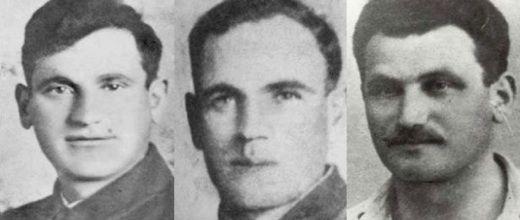

The true story of the Bielski brothers, on which the movie Defiance is based, is actually more interesting than the movie. In the 1930s the Bielski family were grocers and millers (N. Tec, Defiance: The Bielski Partisans, Oxford University Press 1993) in what was then a border town between Poland and the Soviet-Union and now is situated in Belarus. When the Soviet-Union invaded Poland in 1939 on the basis of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the Bielski family collaborated with the communist occupiers as the Polish newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza (Jan. 6, 2009) points out. This resulted in a breach with the predominantly Roman-Catholic Polish population, which saw the Soviets as the oppressors of the Polish language, culture and religion. Ten of thousands Polish officers and intelligentsia were executed and hundreds of thousands ordinary Poles were deported to forced labour camps in Siberia as a direct result of Soviet occupation between 1939 and 1941.

After the German invasion of the Soviet-Union in 1941 the Bielski brothers fled to the Naliboki forest, knowing that they could not hide in their own community as they had no sympathy from the Polish population. In the course of time their hide-out in the forest grew out to a full-fledged Jewish community of more than 1,200 people as other Jews joined them. In the hostile environment under German occupation the Bielski brothers resorted to banditry. They did not have sufficient means in the forest to feed their large community, which meant they had to requisition food and other necessities from the local population by the force of arms. This heightened the friction with the local population, as acknowledged by historian Raul Hilberg: “Food, and everything else they needed, had to be acquired or taken somewhere. One German account noted that Polish peasants, about to be attacked by Jewish ‘bandits’, had beaten thirteen of them to death” (Perpetrators Victims Bystanders: The Jewish Catastrophe, 1933–1945, p. 208). The image of banditry under the guise of partisan warfare is strengthened by Bielski’s own orders: “Don’t rush to fight and die. So few of us are left, we have to save lives. To save a Jew is much more important than to kill Germans.” (N. Tec, Defiance, Ibid., p. 82)

Many Jewish bands had sprang up during the German occupation and some of them actively resisted the occupation, but usually the “partisans” satisfied themselves with easier targets like the local population from which they exacted food in order to survive. The situation in the vicinity of Naliboki was no different: “The town of Naliboki in the Nowogrodek province of Poland was situated near the Naliboki Forest in which partisan units of the Stalin Brigade had set up their base. To survive, much of their time was spent on scavenging for food and clothing in the surrounding villages and towns.” The local population was also terrorized to prevent them from helping the German efforts to stamp out partisan activity. The line between bandits and partisans was very vague and many partisans were accused of looting, rape and murder. The local population was stuck in the middle: both sides requisitioned supplies and any hint of favoritism meant death. As a result, Jewish bands inevitably became involved in war crimes.

One famous account of war crimes by partisans is the Naliboki massacre on the night of the 8th and the 9th of May 1943: “Angered by the widespread plundering, the men of Naliboki decided to fight back and partisan units attacked the town on the night of 8/9, May. All houses were plundered, food and valuables removed, the church and local sawmill burned down as were several houses. The perpetrators in this attack were mostly Jewish communist members of the Stalin Brigade some of whom were former residents of Naliboki and who had earlier escaped from the ghettoes. In the three-hour battle with the defence units of Naliboki, 129 men, women and children were killed.” Note that the church was burned and no quarter was given to women and children. Another infamous massacre in which Jews were involved took place in the village of Koniuchy in the night of 28 to 29 of January 1944: “On the night of 28/29th January about 120 members of the partisan groups and including the Lithuanian Brigade, a Jewish partisan unit of the Red Army, attacked and completely destroyed the village. About forty of those who tried to escape were simply shot down on the spot. Around 300 men, women and children were killed in the 60 households destroyed.”

There is enough reason to believe that at least some members of the Bielski brothers’ band were involved in the Naliboki massacre since they were in the Naliboki forest and aligned with the Soviet partisans. When Defiance was released it caused an uproar in the Polish media, including an article in the Gazeta Wyborcza of June 16 2008, because the movie left out these unpleasant aspects like the terror and atrocities committed against the local population. Some Polish historians branded the Bielski brothers’ as “Jewish-communist bandits.” This image is reinforced by the fact that the Bielski brothers were involved in “some of the over 100 documented clashes between Polish and Soviet forces — fighting on the Soviet side, of course,” according to the Gazeta Wyborcza of 6th January 2009. Besides the Soviets there were also nationalist Lithuanian and Polish partisans. The newspaper also reports that after it was revealed that Polish officers had been executed by the Soviets in Katyn forest, a war broke out between Soviet and Polish partisans: “The Bielski partisans participated, for instance, in the treacherous disarmament of Polish partisans by the Soviets on 1 December 1943.”

The Koniuchy massacre mentioned above is interesting because it has been extensively described by Jewish historians and former Jewish partisans. The first account is Destruction and Resistance (1985) by the Jewish historian Chaim Lazar. The Jewish historian Rich Cohen describes Koniuchy as a ‘pro-Nazi town’ in his account of Jewish partisans in his book The Avengers, despite the fact that Lithuanians and Poles were among the fiercest resisters of German occupation and engaged in almost no collaboration. Recently the Lithuanian prosecutor general has opened an investigation on the Koniuchy massacre and has requested questioning of former Jewish partisans about their involvement. Sara Ginaitė and Yitzhak Arad are two of the Jewish partisans sought for questioning. Ginaitė is a professor of Holocaust studies in York University (Toronto, Canada) and Arad was director of Yad Vashem for 21 years (1972–1993). Arad was a Jewish partisan who joined the NKVD after the Soviet occupation of Belarus and Lithuania in July 1944. The NKVD were the Soviet security forces who carried out the repression and the deportations under the Stalin regime.

The request for interrogation of Arad, who currently living in Israel, caused some stirr in the Jewish media in 2007. The Israeli government branded Lithuania’s request an “outrage” (Haaretz, September 7th 2007) and when the Lithuanian foreign minister visited Israel in February 2008 he got a “harsh letter of protest” form Yad Vashem in which they denounced the investigation of their former director (Haaretz, February 27th 2008). When the Lithuanian prime minister visited New York in July 2008 he was “grilled” by the American Jewish Committee over the “judicial probe” of former Jewish partisans (Haaretz, July 8th 2008). Since then, Jewish-Lithuanian relations have been strained. Lately there has been a row over a list of Lithuanians supposedly involved in the kiling of Jews, which was composed by the director of the Association of Lithuanian Jews in Israel, Joseph Melamed. Lithuania has asked that the list be withdrawn because is contains acknowledged Lithuanian nationalist partisan heroes. As a result, Lithuanian officials were banned from a conference on Lithuanian Jewry held at Yad Vashem (Haaretz September 15th 2011).

If we take all this background information on the Soviet occupation, partisan warfare and the role of Jews in this story, we can dismiss Defiance, the movie version the Stalin Brigade, as a falsification of history. The terror against the local population is totally ignored, as is the role of the nationalist partisans in the fight against the German occupation. It should be noted that the Polish and Lithuanian partisans lived among the locals and were working during the daytime and involved in partisan activity in night time and the weekends. The Jewish partisans are not only exclusively featured but also shrouded with martial glory by depicting a battle with the German forces including a tank, which in fact never took place. Partisans avoided direct confrontation with the superior German forces and focussed mainly on survival and sabotage. The film poster with Daniel Craig carrying a German machine gun (reflecting German tactical prowess and leadership) is highly misleading as it suggests a taste for combat, while actually the Bielski brothers’ band were in hiding. Casting the Nordic-looking Daniel Craig in the role of a Bielski brother can only be described as pure Hollywood.

With regard to the allegations of war-crimes against former Jewish partisans, it is telling that Jews tend to hide themselves behind the moral veil of antifascism, while they were actually willing collaborators of the brutal Soviet occupiers between 1939 and 1944, and complicit in supressing the nationalist aspirations of Poles and Lithuanians, supposedly the reason why Britain and France went to war against Germany. In accounts by Jewish historians the roles are often reversed and Lithuanians and Poles are depicted as Nazi-collaborators who deserved to be killed by Jewish partisans. The cause of “anti-Nazism” seems to justify any crime. Any inquiry by the Polish or Lithuanian governments about the possible killing of innocent civilians by Jewish partisans is met with indignation, animosity and threats. The director of the Association of Lithuanian Jews in Israel Joseph Melamed has made himself clear: “The Lithuanians should think twice before they sue us because it will open up a hornet’s nest.” (Jerusalem Post September 18th 2011) — a threat that is reminiscent of the threats issued by the Jewish partisans against the Lithuanian population during the war.

Comments are closed.