The Limits of Decoding a Nation’s DNA

Review of DNA USA: A Genetic Portrait of America, by Daniel Sykes

Review of DNA USA: A Genetic Portrait of America, by Daniel Sykes

In the foreword to Madison Grant’s The Conquest of a Continent, Henry Fairfield Osborn writes, “The character of a country depends upon the racial character of the men and women who dominate it.” The Olympic games offer a natural display of Osborn’s truism.

Anyone who has watched the 2012 Summer Olympics, particularly the Parade of Nations during the opening ceremony in London — the procession of top athletes from the 204 participating countries — would have noticed the full spectrum of racial distinctiveness across these national delegations. Aliens from another galaxy would have no problem distinguishing the Dutch from Jamaican Olympians.

Westerners are constantly told that “diversity” is a national strength. However, the Chinese Olympians underscore one of Grant’s fundamental points: “the most essential element in nationality is unity.”

Sports “commentators,” such as the ever-annoying Bob Costas, routinely point out that the American Olympic delegation reflects a greater degree of racial and ethnic “diversity” than many other countries. The point isn’t that multiracial national delegations don’t do well in Olympic events. It just isn’t a prerequisite for national achievement. The Chinese have demonstrated this time and again.

Every four years Olympian delegations from around the world showcase individual talent as well as racial and ethnic sexual differences in their competitive performances. In fact, racial patterns dominate various athletic events: Whites and Asians in swimming and cycling events, Blacks in sprinting and basketball. Individual competitors cannot expunge the factors of race, ethnicity, and sex when analyzing group dynamics on a comparative basis.

Recent advances in anthropological genetics are unraveling the migration patterns — “genetic footprints” — of our ancestors. Refinements in genetic testing allow researchers to pinpoint haplogroups along paternal (Y chromosome) and maternal (mitochondrial) DNA clusters. This DNA sequencing is used to identify common ancestors unique to specific populations. Color-coded sections of DNA along both X and Y chromosomes denote European, African, and Asian ancestry. As a result, numerous web-based ancestral services can trace an individual’s genetic heritage to some 36 original paternal and maternal “clans” over several thousand years. Some 30-plus sites offer genealogical DNA testing, including several services that specialize in tracing the genetic roots of Jews and African-Americans.

One of the leaders in this field is Oxford Ancestors. The founder and Chairman of Oxford Ancestors is Bryan Sykes, a pioneering geneticist and author of the first published report that analyzed DNA samples from an ancient bone as well as author of The Seven Daughters of Eve (2002) and Saxons, Vikings and Celts: The Genetic Roots of Britain and Ireland (2006).

One of the leaders in this field is Oxford Ancestors. The founder and Chairman of Oxford Ancestors is Bryan Sykes, a pioneering geneticist and author of the first published report that analyzed DNA samples from an ancient bone as well as author of The Seven Daughters of Eve (2002) and Saxons, Vikings and Celts: The Genetic Roots of Britain and Ireland (2006).

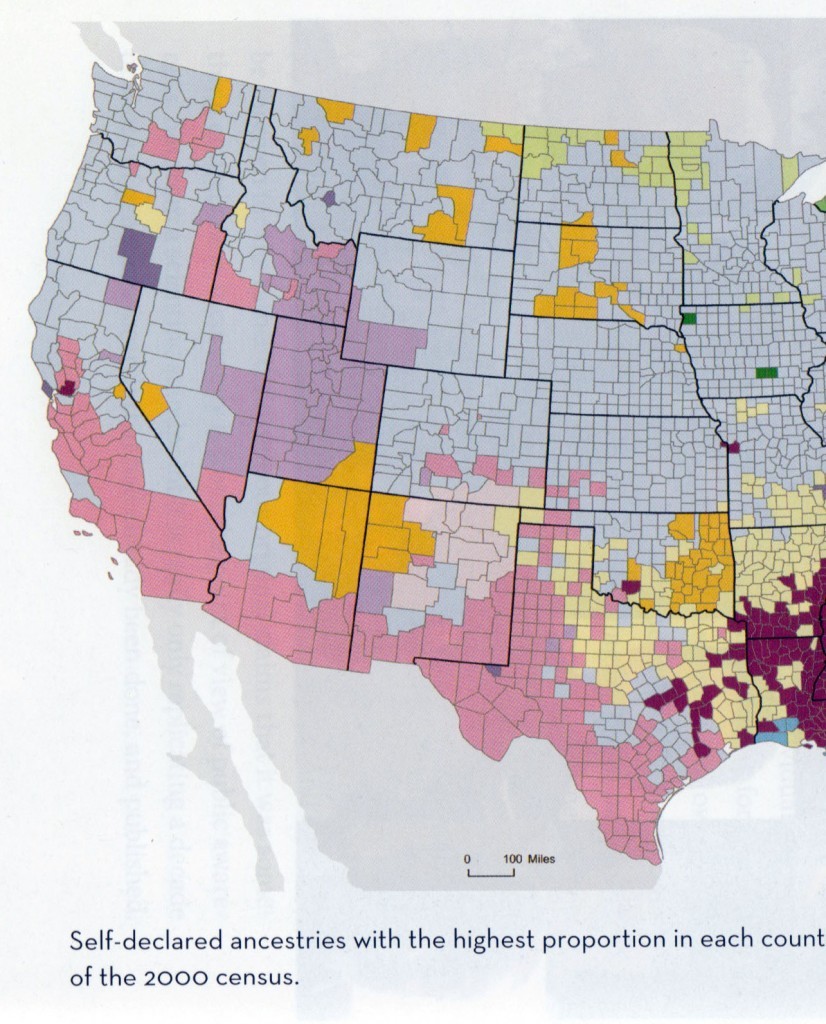

Sykes’s latest book, DNA USA: A Genetic Portrait of America, utilizes recent advances in genealogical testing to map the genetic make-up of Americans. DNA USA is quite possibly the first genetic analysis of its kind — decoding a nation’s DNA — based on small random samples from different populations in different regions. The book is the result of a coast-to-coast tour of America. Sykes and two assistants visited every geographic region meeting various candidates along the way compiling a diverse database of DNA samples for this national portrait. He relates his experiences with the diverse group of volunteers in a lively account that weaves together history, science, and exploration in a folksy journalistic tone. Part Kerouac, part Tocqueville, Sykes’s quest is to unravel the genetic “mosaic” that constitutes present-day America.

What has Sykes and his assistants discovered about Americans?

For one, the genetic record is unclear as to the exact nature and source of the first inhabitants of North America. Were the first Native Americans from northeast Asia or elsewhere? When did the migrations occur? How and where did they arrive on the continent? Did other indigenous migrations simultaneously originate from Polynesia? Further genetic testing could resolve these mysteries, which would require the cooperation of Native American tribes among other things.

Well aware of the controversy surrounding the fossil discovery of Kennewick Man, Sykes is hesitant to reach any conclusion as to Kennewick’s ancestry based on minimal trace samples of mtDNA from the Kennewick remains, because of the possibility of contamination.

The genealogical record of Native Americans, based on DNA testing, lacks sufficient samples for conclusive data, but some preliminary evidence, based in part on carbon dating of fossils, indicates the presence of humans in North America as early as 15,800 years ago. One site near Windover, Florida, excavated in the mid-1980s, contained 177 bodies. Sykes’s own analysis reveals that the Windover data “are highly variable” and consequently unreliable in terms of deciphering the ancestry of those early inhabitants. It’s still speculative as to whether the first Americans arrived from Siberia across the Bering Strait during the last Ice Age or via transatlantic or transpacific voyage, which Thor Heyerdahl was able to replicate in his famous Kon-Tiki expedition in 1947.

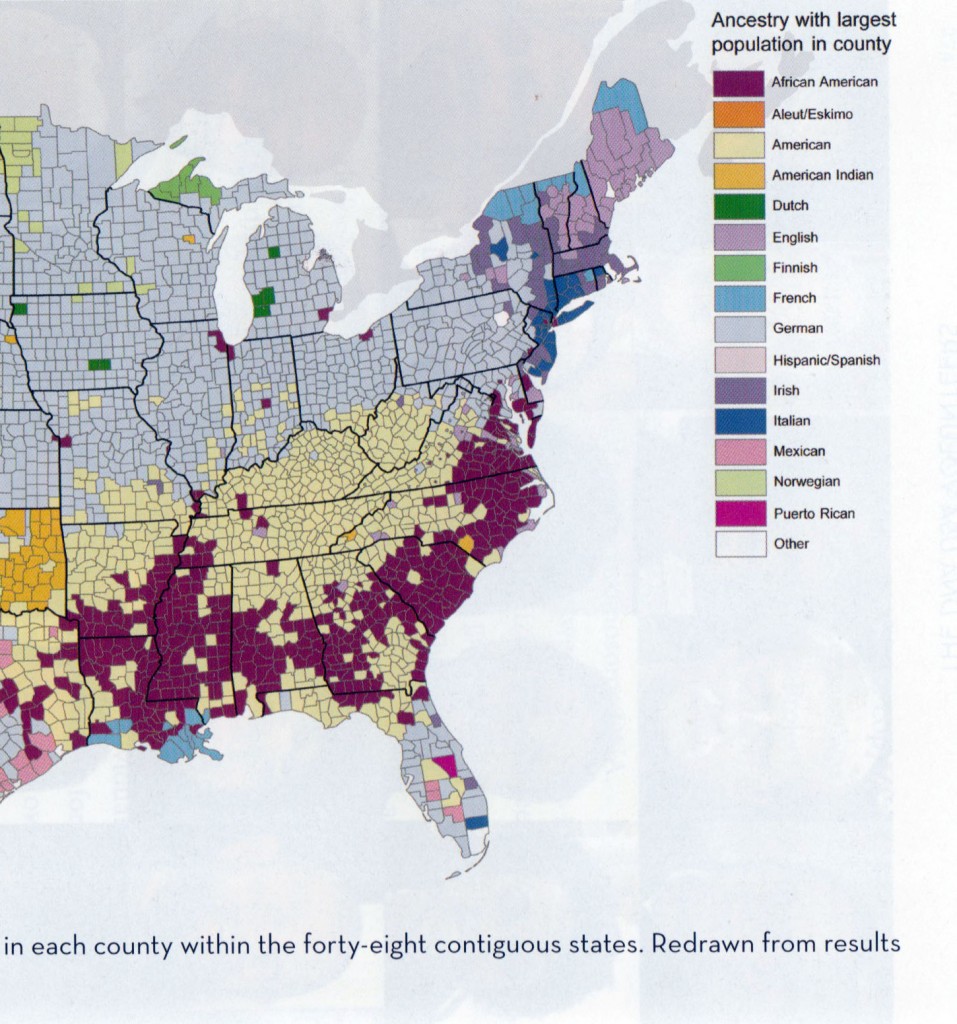

Second, it comes as no surprise that Sykes finds “the numerical dominance of European Americans in large swaths of the United States.” After all, the first settlers in North America were from Europe, America’s founding fathers were of European origin, America’s political, cultural, religious, and civic institutions are based on British and German influences, and the U.S. population is predominantly of European extraction (non-Hispanic Whites constitute 72 percent of the U.S. population based on 2010 census data, nearly three out of four Americans).

Sykes traces the arrival of the first Europeans to the time of the Norseman Explorer Leif Erikson (circa 1002 AD) and highlights early European settlements in North America. One interesting discovery of Sykes’s genealogical research is that New Englanders, historically a bastion of WASPs, seem to have greater genetic homogeneity as descendants of Europeans. In other words, they are less likely to have traces of non-European genes compared to Whites in other regions of the U.S. He claims that Whites in the South are more apt to have some interracial admixture, relative to other regions, in part, because of the large presence of Blacks in that region.

Another interesting but not exactly startling discovery is that one-third of African Americans have some degree of European ancestry. Interest among American Blacks in their African ancestry is quite high, which has led to www.AfricanAncestry.com, a genealogical service founded in 2003 that assists African Americans in tracing their family roots to African countries. Sykes notes that the reaction of American Blacks is often one of shock or denial when confronted with the news that they have some traces of European ancestry in their DNA.

Sykes lampoons Oprah Winfrey’s much-touted “I-am-a-Zulu” claim in 2005. The talk show queen, on a visit to South Africa, stated that she could trace her ancestry to the “Zulu” nation prior to consulting the testing service, which analyzed her DNA, as to the legitimacy of her contention. As Sykes notes, “When the lab results did come back, it was obvious that Oprah’s mitochondrial DNA matched others from West Africa, in particular Liberia, much more closely than anyone from Zululand.”

On the subject of race and racial differences, Sykes is more conventionally ‘PC’ but rejects the sociological “critical-race theory” that race and ethnicity have nothing to do with genetics. On the one hand, he seems levelheaded and realistic, not pulling any punches when discussing ancestral realities; on the other hand, he seems hypersensitive to racial minority perceptions of race differences.

For example, Sykes mentions the 1998 DNA analysis that claimed Thomas Jefferson fathered a child with his mix-raced slave Sally Hemings. The basis for the claim — DNA samples taken not of Jefferson directly but of male descendants of Jefferson’s uncle — has been challenged by Thomas Traut, professor of biochemistry and biophysics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and a commission of distinguished experts who issued a report in 2011 contesting the evidence, which appeared in Nature. Sykes’s summary of the DNA analysis as ultimately conclusive disregards credible discrepancies of the so-called evidence.

There are parts of Sykes’s book that is so ‘PC’ that it ventures into the realm of the ridiculous. He seems to go to great lengths to make sure that no one is offended by his portrayal of America’s “genetic mosaic.” Take for example, Sykes’s description of Henry Louis Gates, the Black director of Harvard University’s W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research, as a “prominent and highly regarded…scholar” during a visit with Gates at the Du Bois Institute. According to Sykes,

Gates could not have been more accommodating when Ulla [Sykes’s assistant] and I met him at the Du Bois Institute in Harvard. He took us on a whistle-stop tour of the institute, where we saw the world’s only hip-hop archive, with recordings, memorabilia, and even the footwear of famous rap stars, and, in separate libraries, a fabulous collection of African and African American art, involving one project titled The Image of the Black in Western Art.

Sykes relates his encounter with Gates, including a dinner with the director of the “Hip Hop Archive” and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, a professor of History and chair of the Department of African and African American Studies, and comments that “Ulla and I have rarely had such an entertaining evening.” As much as this seems like some hilarious scene out of a Tom Wolfe novel, it reflects the extent to which an accomplished scientist is willing to compromise his own credibility in order to avoid any appearance of “insensitivity” as a scholar in a racially “sensitive” area of research. The image of Sykes getting down with rap music at Harvard is ridiculous, but at the same time a horrifying comment on the decline of culture in America.

This patronizing effort has its limits, even in a semi-embarrassing context. Sykes describes his visit to Washington, D.C., which included a meeting with the founders of www.AfricanAncestry and an interview with African American Talk Show host Mark Thompson. Sykes rather anxiously explains how

We got into a taxi and headed for the studios [Sirius/XM] on the other side of town. Gone were the wide boulevards near our hotel, a stone’s throw from the White House. The streets were narrower and the buildings crowded in on us as the taxi weaved in and out of traffic. By now it was dark and the people on the street hard to see. Any sense of unease was soon dispelled by the bright lights of the Sirius XM building….

Someone unfamiliar with the District of Columbia would probably not pick up on the fact that Sykes’s “sense of unease” in a “dark” place “on the other side of town” where the “people on the street [were] hard to see” is because that area in Northeast D.C., near the Sirius/XM studios, is a dangerous Black slum. It is an area that would make the most stalwart egalitarian Englishman nervous to the point of breaking out with a bad case of shingles. Loitering is rampant, and shootings and muggings are frequent.

Another shortcoming of DNA USA is putting the “genetic portrait of America” into some interpretative context. In other words, drawing out reasonable inferences and likely implications of America’s demographic changes. The findings appear in a vacuum, relatively speaking. If America’s largest ancestral group continues to diminish to minority status by 2050, what does this mean for our institutions?

Serious scholars such as Sykes should abandon the ‘PC’ window-dressing and let the facts speak for themselves. Applauding the work of a director of a “hip hop archive” or comparing one’s adventurous research endeavor to the protagonists in Easy Rider undercuts one’s credibility. John Randall Baker, arguably the most objective preeminent authority on the biology of race, set a high standard for researchers to follow. Unfortunately, Sykes’s latest work on America’s genetic profile aims a little lower.

Comments are closed.