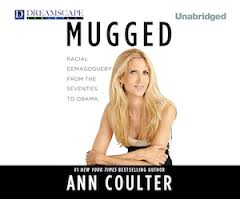

Race Relations 101 with Ann Coulter

Mugged: Racial Demagoguery from the Seventies to Obama

Ann Coulter

Sentinel (a division of Penguin), 2012

$26.95, 326pp.

In more ways than one, Ann Coulter stands out among “conservative” commentators. Her feisty, tart, hard-edged prose and photogenic allure — coupled with her gusto to address issues most “conservatives” deliberately avoid — have generated a loyal following among grassroots activists on the Right.

As a bestselling conservative author, Coulter’s high-profile status makes her a walking target for liberal critics. Pushing the envelope is her trademark practice, especially on cultural and social issues, which infuriates the Left. Consider: her defense of Joseph McCarthy; her admiration for the writings of the late Joseph Sobran; her claim that The Bell Curve is one of her favorite books; and her quip that her “only regret with Timothy McVeigh is that he did not go to the New York Times Building.” Not to mention her defense of the Council of Conservative Citizens, which earned her the tag “Rabid far-right commentator” from the SPLC. All of this positions Coulter in the company of Pat Buchanan well to the right of the conservative establishment.

Coulter’s latest book, Mugged: Racial Demagoguery from the Seventies to Obama, pushes the envelope to the table’s edge. It offers a perceptive — and at times blistering — assessment of race relations from the vantage point of a right-wing skeptic. In terms of social commentary, Coulter rivals H. L. Mencken’s witty barbs when it comes to lampooning opponents. Her critique of the hollow mantra of “racism” offers clear-headed commonsense to the conventional media portrayal of America as a bastion of “racism.”

This topic is ripe with low-hanging fruit. For example, CNN Presents produced a blatantly biased show on the Rodney King phenomenon, Race Rage, the Beating of Rodney King, hosted by Don Lemon. Early in the broadcast viewers see Rodney King explain to Lemon how he ever so innocently “went up like that with my hands up and showed no threat.” Coulter strips away the façade of King as some ordinary motorist out for a spin when cops stopped and pulverized him. “In fact, what the public saw was the officers’ final efforts to subdue a deranged suspect after all other methods proved futile.”

From the 1970s to the “post-racial era” of the Obama years, Coulter dissects numerous episodes of media-hyped racial turmoil: Bernard Goetz, Tawana Brawley, several high profile “police brutality” cases (including Rodney King), the O.J. Simpson trial, the Peoples’ Temple cult massacre led by Marxist zealot Jim Jones, the Los Angeles riots, and a host of others.

Never one to miss an opportunity to slam the New York Times, Coulter heaps on the criticism in her chapter, “Innocent Until Proven White,”

Any violence committed by a white person against a black person was the occasion for marches, rallies, and conclusion jumping. Inasmuch as a white person physically attacking a black person was remarkably rare, the majority of these cases involved police officers. Every black person who was shot by the police, or who died in police custody, throughout the 1970s and 1980s, became a beloved member of our community, killed by racism. Most people will generally take the word of a cop over that of a criminal, but most people are not reporters for the New York Times.

Coulter takes the press to task for striking the match that lit the fuse and sparked the L.A. riots: the heavily edited videotape of the Rodney King incident publicized by KTLA, the Los Angeles television station. The excessive nature of the press coverage, which repeated the edited video footage ad infinitum, stoked much of the racial violence during the aftermath of the Simi Valley verdict which resulted in the acquittals of three officers and a deadlocked decision on one. These officers had been essentially put on trial for following police procedures in attempting to subdue and arrest King — a belligerent motorist and convicted felon with a history of domestic violence, alcoholism, and drug abuse, which cost him his life on June 17, 2012. (Toxicology results showed that alcohol, cocaine, and marijuana were contributing factors in King’s “accidental” drowning in his swimming pool.)

Coulter also reminds those of us old enough to remember what Al Sharpton was really like during his peak years as a demagogue. (See also the “Mainstreaming Demagoguery: Al Sharpton’s Rise to Respectability” by the National Legal and Policy Center.) Sharpton has re-invented himself as a media celebrity and political analyst. However, his heavy hand in the Tawana Brawley rape hoax, which prompted a defamation of character legal judgment against Sharpton and two others for $345,000. Sharpton became famous for a series of high-profile racial protests, including after the notorious Crown Heights riot, where Blacks looted stores in an Orthodox Jewish neighborhood, killing two people, a Jew and a non-Jew mistaken for a Jew. Another Sharpton protest was against the owner of Freddie’s Fashion Mart for evicting a Black sub-tenet, which provoked one protestor to shoot-up and torch the store. As Coulter explains:

Surely, after all this, Sharpton became a pariah — oh wait! No, that’s not what happened. Far from being exiled, he became famous, ran for president and Al Gore kissed his ring, after these events. Instead of becoming kryptonite, Sharpton became rich, famous, and a Democratic power broker.

The fact that MSNBC has ignored Sharpton’s sordid past, which includes an FBI videotape of Sharpton attempting to purchase cocaine. MSNBC also rewarded him with his own primetime program while the network “parted ways” with longtime political analyst and three-time presidential advisor Pat Buchanan. MSNBC president Phil Griffin decided that the “ideas [Buchanan] put forth [in Suicide of a Superpower] aren’t really appropriate for national dialogue, much less the dialogue on MSNBC.” MSNBC is nothing if not a blatantly radical version of politically correctness.

In a section on Jim Jones’s Peoples Temple, Coulter rakes MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow over the coals in her description of cultist Jim Jones:

MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow called Jones “a minister from a small town in Indiana” — which is on the order of calling Charles Manson a petty thief from Cincinnati. They both hit it big in spaced-out, left-wing New Age California.

Coulter hits her rhetorical stride when she’s lampooning the ridiculously obvious. A couple of favorites pertain to the O.J. Simpson trial: “In 1995, Americans discovered it was considered a graver offense to use ‘the N-word’ than to cut a woman’s head off.” And this sizzler a few pages later:

The defense team had hired OJ’s accomplice, Robert Kardashian, as a lawyer solely to prevent him from being asked about the bulging Louis Vuitton garment bag he was seen carrying away from OJ’s residence the day after the murder, leading to speculation that the bag contained bloody clothes and the murder weapon. This constituted the second worst thing he ever did after spawning the Kardashian sisters.

Then there’s this observation about Obama’s racial demagoguery:

Obama’s autobiographies — there’s more than one! — are bristling with anger at various imputed racist incidents. As biographer David Maraniss says, Obama sees the world through a “racial lens,” presenting “himself as blacker and more disaffected than he was.” He’s spent his life hungry for reasons to be angry.

Coulter is also great at exposing racial falsehoods and pinpointing double-standards in the mainstream media. She uses a matchless wit and sarcasm to skewer Chris Mathews and Rachel Maddow and is fond of scouring the spotty record of high-profile Black “activists,” such as Johnny Cochran, Jeremiah Wright, David Dinkins, Alton Maddox, C. Vernon Mason, and Louis Farrakhan.

Coulter argues that the O.J. Simpson trial was the end of White guilt, “Unknown to the elites, the world changed at 10:07 a.m. on October 3, 1995, when an estimated 150 million people turned on their TVs to watch the verdict. As blacks across the country erupted in cheers at the acquittal, it was the end of white guilt in America.” In her final chapter, “White Guilt Kills,” Coulter writes, “White people using elections to prove that they like black people has never turned out well.” If anything, the election of Obama in 2008 reveals that the “end of white guilt” was a fleeting reality.

According to Coulter, middle-class White guilt explains the disconnect between implicitly White actions, such as moving to all-White enclaves in semi-rural areas or engaging in activities White people like (golf, beach trips, NASCAR events, bowling, polo, garage sales, collecting antiques, military reenactments, major league baseball games, etc.) while voting in droves to elect Obama President (rated one of the most radical U.S. Senators in the 110th Congress), even though he lacked minimal qualifications for the nation’s highest office. Coulter barely scrapes the outer edges of this phenomenon; more thorough scrutiny could easily fill another volume.

However, the book has its shortcomings. She argues that the O.J. Simpson trial was the end of white guilt: “Unknown to the elites, the world changed at 10:07 a.m. on October 3, 1995, when an estimated 150 million people turned on their TVs to watch the verdict. As blacks across the country erupted in cheers at the acquittal, it was the end of white guilt in America.” In her final chapter, “White Guilt Kills,” Coulter writes, “White people using elections to prove that they like black people has never turned out well.” If anything, the election of Obama in 2008 reveals that the “end of white guilt” was a fleeting reality.

Middle class white guilt explains the disconnect between implicit white actions, such as moving to all white enclaves in semi-rural areas or engaging in largely white activities (golf, beach trips, NASCAR events, bowling, polo, garage sales, collecting antiques, military reenactments, major league baseball games, etc.) and voting in droves to elect Obama President (rated one of the most radical U.S. Senator in the 110th Congress), who lacked minimal qualifications for the nation’s highest office. Coulter barely scrapes the outer edges of this phenomenon when more thorough scrutiny could easily fill another volume. One would think that 150 million viewers watching blacks cheer at the verdict in the Simpson trial would send an unforgettable message to whites, but apparently not.

As good as it is, Coulter’s latest book-length jab at liberalism contains other flaws. Al Sharpton, Jesse Jackson, Jeremiah Wright, Rodney King, Louis Farrakhan, and Obama are easy targets for conservative pundits. Nevertheless, the rhetorical tactic of deploring liberal Democrats for their implicit and explicit “racism” while praising Republicans for their sincere pro-civil rights record is dubious and intellectually dishonest. Barry Goldwater, as well as other Republicans and Democrats, articulated sound reasons for opposing the 1964 Civil Rights Act. It is true that most of the segregationists in Congress, including members of the “Southern Caucus” in the U.S. Senate, were Southern Democrats, but some were liberal and others conservative. Coulter can distance herself from these advocates of segregation with more nuanced arguments instead of employing blanket accusations that Democrats are to blame for the failings of Blacks. It is simply slipshod logic and a bit ridiculous to attack “racism” on the grounds that liberal Democrats are racist but authentic conservative Republicans are champions of “civil rights.”

Another flaw in Coulter’s work is the overuse of kitschy simplicity at the expense of substantive analysis. Ripping up one’s adversaries in sarcastic prose has its limitations. As a successful conservative author, Coulter’s situation is understandable. Her status and income depends on avoiding the quicksand nature of politically incorrect scandals. If one is dependent on swimming in shark-infested waters, one has to avoid bloody injuries. Standing firm on principle has cost Buchanan financially with the loss of a lucrative network contract; Coulter has been able to skillfully maneuver through a minefield of career-ending controversies and remain above the fray as a best-selling author. The downside is that she limits her intellectual fire to simply describing her targets rather than dealing with the underlying substantive issues—for example, racial differences in traits, values, norms of behavior, judgment, etc. This leaves a vacuum of inexplicable causation. Any honest discussion of the problems of U.S. race relations must inevitably address the topic of the origins of race differences in educational achievement, criminality, family stability, and economic success. Tip-toeing around the elephant in the room perpetuates fallacies as the sources of racial disparities, namely the endless indictment of White racism, police brutality, or economic inequalities resulting from “White skin privilege.”

Is liberalism the sole explanation for the uncivil behavior of blacks? Is the history of troubled race relations simply the result of “racist” Southern Democrats? The ultimate causes of racial disparities in educational outcomes, arrest and incarceration rates, health, longevity and mortality rates, and dozens of other indicators must be attacked head-on. In his Race, Evolution and Behavior, Philippe Rushton has provided the most comprehensive scientific theory of racial differences in all these traits — a theory that explains the co-occurrence of the particular suite of traits seen in Blacks around the world. Another important contribution has been Michael Levin’s Why Race Matters, an unsurpassed exploration of the subject. Employing disingenuous arguments to deflect charges of “racism” is an exercise in futility.

Mugged is worth reading, if for nothing else the sheer enjoyment of a gifted writer’s take on a burning social issue, but Coulter’s account is marred by unnecessary deficiencies.

Comments are closed.