“The Large-Scale Death”: The Massacres of Bleiburg and Viktring

Review of The Tragedy of Bleiburg and Viktring, 1945 by Thomas Rulitz

Review of The Tragedy of Bleiburg and Viktring, 1945 by Thomas Rulitz

Packaging is often of more decisive importance than content. This is particularly true today for many fine authors and their works in the field in humanities and especially in the field of modern history. For the reasons of politically incorrect content or due to editorial self-censorship, their works often fail to attract the largess of mainstream publishing houses. It has become a customary procedure for the System to relegate free thinkers and would-be heretics and their literary or scientific achievements to marginal outlets, such as self-publishing, that are very similar to those used by dissidents in the ex-Soviet Union.

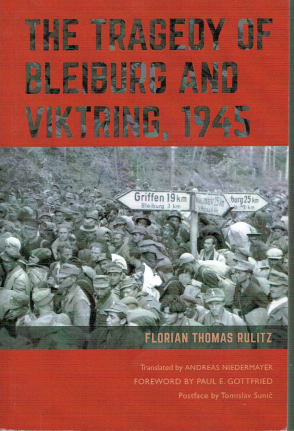

However, both by its approach and by the huge number of citations from opposing sources, the recent book by the young Austrian historian, Dr. Florian Thomas Rulitz, The Tragedy of Bleiburg and Viktring,1945, may be an exception to this unwritten rule. This book was recently published in English translation by Northern Illinois University Press, and it also contains a fine foreword by Paul Gottfried, a prominent scholar.

One merit of the author is that he taps into archives across the ideological board, quoting extensively from ex-Yugoslav communist archives, British archives, and German military archives. He also provides facsimiles and eyewitness accounts by surviving Croat and German expatriates. The book has 300 pages, out of which over a third are quotations, references and bibliographical notes.

After a long period of deafening silence, this well-researched book on the Allied and Yugoslav communist crimes against hundreds of thousands of disarmed Croat Axis soldiers and civilians, including summary executions of a significant number of disarmed anti-communist Slovene, German and Serb “enemy combatants,” is finally seeing the light of the day. It will certainly prompt a somewhat different narrative on the standard World War II antifascist victmhoods and provide a more objective picture of the so-called new democratic order, established after 1945. What follows below is my afterword.

* * * * *

Dr. Florian Thomas Rulitz depicts Viktring and Bleiburg, two towns in Austria that are memorial sites of the post-World War II Yugoslav Communist massacres. Viktring and Bleiburg also happen to be symbols of the plight for thousands of Croatian Axis soldiers and civilians in the wake of World War II. The picture of the Bleiburg tragedy gets even more complete if one takes a glimpse at the numerous bays dotting the coast around the nearby Istrian peninsula where in the summer of 1945 large numbers of German soldiers, along with many Italian and Croatian refugees, were murdered by the Yugoslav Communist military units, and whose fate became similar to that of ethnic Germans (“Volksdeutsche”) in Croatia’s hinterland. Rulitz’ book makes it clear that Croatia and Carinthia were not just areas designed for mass tourism, but also locations of massive death. When reading Rulitz’ book one may add that the pastoral and poetic nature of southern Carinthia, where the towns of Viktring and Bleiburg are located, swallowed up in May 1945 civilians and soldiers from other European countries who happened to be fighting on the losing side of the historical barricade. In the decades to come, however, there were contingents of anonymous citizens from central and southeastern Europe who took the same route of Viktring and Bleiburg—albeit this time in order to flee to the much cherished Western capitalist freedom.

A major problem in modern historiography is that when describing the “struggle for historical remembrance,” not all victims enjoy the same privilege of commemoration. Judging by the modern media body counts, someone’s World War II dead must have priority, while someone else’s dead are meant to slide into oblivion. In Croatian historical awareness the word “Bleiburg” has a special meaning, just like the word “Viktring” has a specific meaning for the Slovenes and for the inhabitants of Austria’s Carinthia. Indeed, in the Croatian language the word “Bleiburg,” does not evoke the images of pristine woods, skiing holidays, or a new shopping center. For many Croats this word has become a metaphysical locution designating a horrific example of catastrophically failed nation-state building. Bleiburg is not a symbol of a picturesque and romantic location, but a road sign of Croatia’s sociobiological catastrophe. By the late May 1945, hundreds of thousands of fleeing Croats, along with some Cossacks, Montenegrins, Serbs, and Slovenes, were extradited from there to Tito’s Yugoslav partisans—courtesy of the Allied English troops in the vicinity.

When reading Rulitz’ book, one may also recall millions of expelled Germans from Silesia, Pomerania, eastern Germany, the Sudetenland and the Danube region. (See here and here). With the double standards in the description of diverse victimhoods, which are still well alive in the modern historiography, their commemoration is hardly to be the case any time soon. As was once noted by the renowned German scholar of constitutional law, Carl Schmitt, modern historians’ battle with diverse victimhoods constitutes a serious problem for modern international law-makers, let alone for an objective study of history. Many modern media reporters, including a sizeable number of academics, are often tempted to describe those hapless masses of disarmed Croat Axis soldiers and civilians in the Carinthian fields in the summer of 1945 as “fascist monsters” or “vermin.”

Well, if one were to accept such a demonological narrative, there is no way one can apply the legal precepts of human rights to them either. Monsters or demons cannot have a memorial site. Monsters, being non-human extraterrestrials, do not deserve a place of remembrance. They deserve death only.

Modern historians and opinion makers also tend to forget that a one-sided body count always causes new conflicts. A one-sided victimology insists on its own uniqueness at the expense of the uniqueness of others’ victimologies. In today’s multicultural Europe or America, such victimological atmosphere makes every nation, every community, let alone every non-European migrant believe in the importance and uniqueness of his own victimology. Moreover, victimologies love competing with each other. A victimhood mentality, especially if exaggerated, does not help prevent future conflicts, nor does it secure peace. Rather, it leads to renewed violence, thus making the spiral of hatred unavoidable. The blueprint of such one-sided victimhood was set up on the eve of the breakup of the former state of Yugoslavia, a state in which the decades-long, one-sided, semi-mythical Yugoslav-sponsored communist victimology only ignited war in 1991. Communist Yugoslav historians had never attempted to create a climate of mutual understanding among the Yugoslav peoples. In fact, they share the blame for the carnage that followed the breakup of Yugoslavia.

Rulitz’ book is a solid document on the little-known Bleiburg tragedy. One can only hope that it will someday be read by EU politicians who may hopefully reconsider their cherished dreams of yet another multicultural Yugoslav-style European utopia. The lessons of Bleiburg may serve as a warning.

Zagreb, January 2016

Comments are closed.