Review of Kerry Bolton’s “Yockey: A Fascist Odyssey”

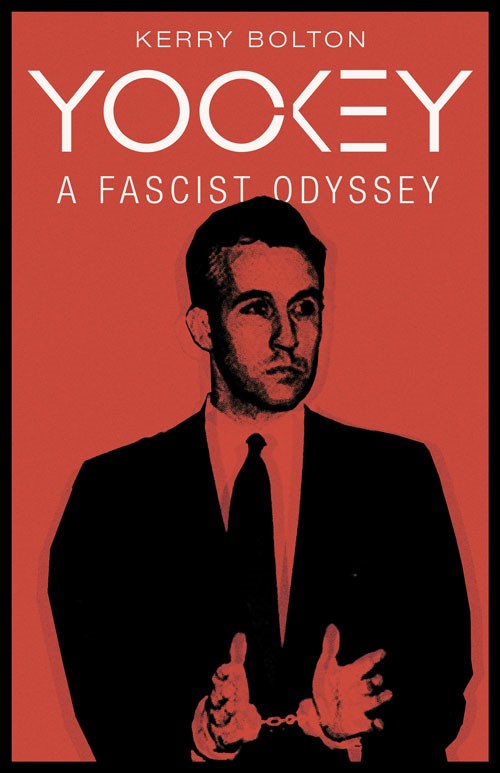

Kerry Bolton, Yockey: A Fascist Odyssey (Arktos, 2018)

What follows is my foreword to Kerry Bolton’s recently released book on Francis Parker Yockey.

This is the first time an exhaustive work on the prominent Euro-American Fascist activist and philosopher, Francis Parker Yockey, is being offered to a wide readership in the English-speaking world. Naturally, for starters, a big question that comes to mind immediately is, “what’s the point of reading Bolton’s thick book and how relevant is Yockey’s anti-Communism and anti-Liberalism in dealing with the ongoing decay of the multicultural West, which is currently subject to an open invasion of non-European masses?” Since Bolton often uses the German word “Zeitgeist” in his description of the dominant political ideas of Yockey’s time, a neophyte might likewise wonder if and how Yockey’s political prognoses are being validated by the dominant political ideas of our time. For many nationalist old-timers, both in Europe and America, Yockey is a household name that is indispensable in studying the intellectual developments of cultural Fascism, yet, for many young identitarians today, regardless whether they sport the name Alt-Right, New Right or Traditionalists, the name Yockey, along with his magnum opus Imperium, may sound a bit outdated. However, several years ago, when Bolton started writing this book, he was already aware that Yockey, with all his literary baggage and world-wide acquaintances, would today become more relevant than when he was alive. This is despite the fact that Yockey’s Bolshevik archenemies with their iconography of the cosmopolitan and borderless proletariat have been replaced with a new Liberal imagery of mixed-raced and stateless pederasts accompanied by masses of non-European migrants. Yockey’s enemies are alive and well—even thriving, irrespective of their change in ideological color.

As far as the composition of the book is concerned, Bolton provides a wide historical-literary framework in which Yockey serves as a springboard, or better yet, as a framework for a better understanding of similar and like-minded authors and political protagonists of his time. Bolton first goes into the clarification of political concepts and their semantic distortions that have been orchestrated by the victorious Communist and Liberal elites over the last seventy years. While using Yockey as a guide, Bolton sheds additional light on the values of the modern system which keeps rewriting the intellectual history of the West as it best fits its mercantile and rootless agenda. “A System that once produced Shakespeare but now produces sitcom scriptwriters; that once birthed Beethoven and Mozart but now lauds Lady Gaga.”

This process of cultural degeneration did not, however, start with Lady Gaga or the recent welcoming calls to millions of non-White migrants. It has its roots in the eighteenth-century Enlightenment and its political offshoots in America and France. The then discovered secular religion of human rights gave birth subsequently to Communism and then to its modern ersatz version, multiculturalism. The following chapters also explain how the reception of Yockey’s work varied among different European and American identitarians, with some calling Yockey “anti-American” and with others praising him to the heavens.

Yockey’s criticism of “Americanism” and the “money-based Puritan culture of WASP America, where Jews … could buy their influence,” must have played a role after World War II in landing him on the FBI’s radar screen. His critical remarks about American Jews and their role in the media—the combination of which we call today in a coded language “fake news”—earned him a great deal of intellectual respect among prominent European nationalist scholars who had traditionally looked down upon America as a wayward, uncultured entity dominated by Jews. Yockey’s openly pro-German stance, especially when serving as a young attorney at the Wiesbaden show trials in 1946, must have been seen as an additional irritating detail for the American ruling class and several Jews on the bench. His openly pro-European, anti-Communist and anti-Liberal attitudes may be compared today to the views of some segments of the American Alt-Right, who without awareness, are walking in Yockey’s footsteps, realizing that petty nationalist inter-White squabbles, tribal infighting amidst traditionalists, racialists, right-wing Catholics, Protestants, and Pagans, are outdated and need to go away.

One name that repeatedly springs up in Bolton’s pages is Oswald Spengler. Indeed, the whole of Yockey’s work must be seen as a sequel to Spengler’s The Decline of the West, where Yockey radically rejects the money-obsessed capitalist West and its beacon, America. It is to the merit of Bolton who doesn’t just drop the names of dozens of American and European authors, scholars, and activists, some of whom were close friends and acquaintances of Yockey, but instead, he tries to explain the context or background behind each person, organization and political concept under consideration. This is important insofar as in Bolton’s text the reader comes across numerous terms such “ethical socialism” or “Prussian socialism,” with which Yockey is often associated, whose historical meaning, however, needs to be further explained to younger Yockey readers. Bolton’s pages are literally teeming with quotes and citations, particularly in the realm of modern historiography and legal studies and in the chapters where Bolton examines the myth of the so-called freedom-loving West. The post-World War II mass shootings of thousands of German POWs and mass rapes of German women were not just part of a well-recorded folklore among Soviet soldiers in vanquished Germany, but also a customary, albeit well-hidden, escapade of many British and American soldiers “showing the extent of the torture regime against Germans after the war.”

Nowadays, we may all fake concern for victims of mass purges and Communist killing fields in Eastern Europe in late 1945. However, one does not need to speculate much about those who served as role models to East European Communists. Following World War II, Communist prosecutors and henchmen in Eastern Europe were only copying in a more brutal way the same techniques of their former war allies. Well, the chickens have finally come home to roost. The new Brussels–guided liberal governance in Eastern Europe is largely staffed by former Communist apparatchiks, or to put it more precisely, by the rebranded progeny of former Communist cut-throats—with the full blessing of the “free West.”

Yockey was a multilayered and complex character bursting with intellectual curiosity, as indicated by Bolton’s descriptions dealing with Yockey’s numerous peregrinations across Europe and his contacts with prominent post-fascist literati and aspiring nationalist leaders—at least those who had managed to evade the Allied rope. Ironically, the Western and American Liberal world-improvers, at the beginning of the Cold War, were willy-nilly obliged to tap into the expertise of their former foes. As Bolton chronicles, Yockey was on good terms with numerous post-Fascist figures, such as Giorgio Almirante, once a high-ranking politician in the late Mussolini government, who at the beginning of the Cold War played an important role in regrouping Italian nationalists. Also, Yockey nurtured ties with Sir Oswald Mosley, the former leader of the British Union of Fascists (BUF), as well as with the short-lived post-World War II political party, the Socialist Reich Party of Germany (SRP), which had regrouped a large number of former National-Socialist members and former SS officers.

Again, we need to revisit the famed notion of the “Zeitgeist,” i.e., the spirit of the times, which, back when Yockey was alive, was very diffuse and liquid on all fronts. On the one hand, staged trials and constant surveillance of former Nazi “killers” were running full steam in the Eastern and Western jurisprudence. On the other, the Western occupying forces, headed by the American world-improvers, were getting ready for a full-scale military conflict against their former ally, the Communist Soviet Union. Hence, the reason they needed to rely on the expertise of their former Fascist foes. It is often forgotten that at the start of the Cold War, the occupying American authorities in Germany were reliant upon former German SS operatives, just as the build-up of the early Bundeswehr would have been nearly impossible without the prior consent of some former Wehrmacht officers.

One may raise an additional philosophical question which certainly crossed Yockey’s mind when he had landed in prison in 1960, “what would have happened if the Soviets and the Americans had entered into the military conflict by the early 1950s?” It is not hard to guess that Yockey himself would have likely played an additional historical role in America and Europe and that his book Imperium would have likely shaped a new form of the Zeitgeist in students’ curriculum.

Bolton’s pages read like a lengthy, detailed police report on hundreds of unknown or forgotten individuals who nevertheless played an important role in determining Yockey’s fate, and who themselves had an enormous impact on future political developments in Europe and America. Also, Bolton tackles the unavoidable theme of American Jews who were portrayed by Yockey and his fellow travelers as far more dangerous than Soviet Jews. Besides having archival value, this book is an important tool in studying the ongoing practice of criminalizing and pathologizing political opponents by the false use of the worn-out word “fascism.” This word, which has by now totally lost its original meaning, has become a word meant to silence political opponents and prevent serious scholarly inquiry. If the liberal-minded President of the United States, Donald Trump, or the liberal German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, are denounced by their detractors as “fascists,” then one must also give full credit to Yockey for trying to restore the true and original meaning of this word.

Comments are closed.