The “Extraordinary Successful” Aristocratic Individualism of Indo-Europeans – Chapter 2 of Individualism

Part 2 of my detailed examination of Kevin MacDonald’s Individualism and the Western Liberal Tradition: Evolutionary Origins, History, and Prospects For the Future (2019), examines his emphasis in chapter two on the aristocratic individualism of Indo-Europeans. In Part 1 I covered MacDonald’s argument in chapter one that Europe’s founding peoples consisted of three population groups:

- Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHGs) who were descendants of Upper Paleolithic peoples who arrived into Europe some 45000 years ago,

- Early Farmers (EFs) who migrated from Anatolia into Europe starting 8000 years ago, and

- Indo-Europeans (I-Es) who arrived from present-day Ukraine about 4500 years ago.

Using MacDonald’s argument, I emphasized how these three populations came to constitute the ancestral White race from which multiple European ethnic groups descended.

The task MacDonald sets for himself in chapter two is a most difficult one. He sets out to argue that the most important cultural trait of Europeans has been their individualism, that this trait was already palpable in prehistoric times among WHGs and I-Es, that it is possible to offer a biologically based explanation for the emergence of this individualism, and that this individualism was a key component of the “extraordinary success” of Europeans. How can one employ a biological approach to explain individualistic behaviors that seem to defy a basic principle of evolutionary psychology — that members of kin groups, individuals related by blood and extended family ties, are far more inclined to support their own kin, to marry and associate with individuals who are genetically close to them, than to associate with members of outgroups? It is also the case that the concept of “group selection”, to which MacDonald subscribes, says indeed that groups with strong in-group kinship relationships are more likely to be successful than groups in which kinship ties are less extended and individuals have more room to form social relations outside their kin group.

Evolutionary psychologists prefer models that explain group behavior in animals and humans generally. They also prefer to talk about cultural universals — behavioral patterns, psychological traits, and institutions that are common to all human cultures worldwide. When they encounter unusual cultural behaviors, they look to the ways in which different environmental settings may have resulted in genetically unique behaviors, or to the ways in which relatively autonomous cultural contexts may have promoted or inhibited certain common biological tendencies.

MacDonald combines these two approaches to argue that the individualism of Europeans is a genetically based behavior that was naturally selected by the unique environmental pressures of northwest Europe. However, it is only in reference to the egalitarian individualism of northwestern hunter gatherers, which is the subject of chapter three, that MacDonald tries to explain how this egalitarian individualism was genetically selected. He takes it as a given in chapter two that the I-Es were selected for their own type of aristocratic individualism, without linking this individualism to environmental pressures in the Pontic steppes. In Part 3 we will bring up his argument about how Europe’s egalitarian individualism was naturally selected.

Cultural Peculiarities of Indo-Europeans

My emphasis in Uniqueness was less on the looser kinship ties of I-Es than on the “aristocratic egalitarianism” that characterized the contractual ties between warriors — how the leader, even when he was seen as a king, was “first among equals” rather than a despotic ruler. MacDonald emphasizes both this aristocratic trait and the ways in which I-Es established social relations outside kinship ties.

I-Es were aristocratic in the true sense of the word: men who gained their reputation through the performance of honorable deeds, proud of their freedom and unwilling to act in a subservient manner in front of any ruler. In addition to, or as part of the Männerbund, “guest-host relationships (beyond kinship) where everyone had mutual obligations of hospitality”, and where “outsiders could be incorporated as individuals with rights and protections,” were common among these aristocrats. By the time the Yamnaya migrated into Europe some 4500 years ago, they had developed a highly mobile pastoral economy coupled with the riding of horses and the development of wagons, in the same vein as they initiated a “secondary products revolution” in which animals were used in multiple ways beyond plain farming, for meat, dairy products, leather, transport and riding. This diet, together with the open steppe environment, where multiple peoples competed intensively to support a pastoral economy requiring large expanses of land, encouraged a highly militaristic culture. Indo-Europeans became a most successful expansionary people: Currently 46% of the world’s population speaks an Indo-European language as a first language, which is the highest proportion of any language family.

Individualism and Ethnocentrism Among Ancient Greeks

But it could be that MacDonald does assume that, in the degree to which Europeans created social ties outside kinship ties, it would have been inconsistent for them to retain kinship affinities and ethnocentric tendencies. He observes that “despite the individualism of the ancient Greeks, they also displayed [in their city-states] a greater tendency toward exclusionary (ethnocentric) tendencies than the Romans or the Germanic groups that came to dominate Europe after the fall of the Western Empire” (48).

The Greeks had a strong sense of belonging to a particular city-state, and this belonging was rooted in a sense of common ethnicity…The polis was thus…exclusionary (serving only citizens, typically defined by blood)…Greek patriotism based on religious beliefs and a sense of blood kinship was in practice very much focused on the individual city, making those interests absolutely supreme, with little consideration for imperial subjects, allies, or fellow Greeks in general (48-49).

I don’t think it should surprise us that despite their individualism the Greeks had a conception of citizenship defined by kinship. I would argue, rather, that it was precisely their individualistic detachment from narrow clannish ties that allowed the Greeks to develop a new, wider and more effective, form of collective ethnic identity at the level of the city state. Citizenship politics was introduced in Greece in the seventh century BC as a challenge to the divisive clan and tribal identities of the past. A citizen in a Greek city-state was an adult male resident individual with a free status, able to vote, hold public office, and own property. Bringing unity of purpose among city residents, a general will to action to communities long divided along class and kinship lines, was the aim behind the identification of all free males as equal members of the city-state.

As I argued in “The Greek-Roman Invention of Civic Identity Versus the Current Demotion of European Ethnicity“:

We should praise the ancient Greeks for being the first historical people to invent the abstract concept of citizenship, a civic identity not dependent on birth, wealth, or tribal kinship, but based on laws common to all citizens. The Greeks were the first Westerners to be politically self-conscious in separating the principles of state organization and political discourse from those of kinship organization, religious affairs, and the interests of kings or particular aristocratic elites. The concept of citizenship transcended any one class but referred equally to all the free members of a city-state. This does not mean the Greeks promoted a concept of civic identity regardless of their lineage and ethnic origin […] The Greeks…retained a strong sense of being a people with shared bloodlines as well as shared culture, language, mythology, ancestors, and traditional texts.

City-states were indispensable to forge a stronger unity among city residents away from the endless squabbling of clannish aristocratic men, for the sake of harmony, the ‘middle’ good order. To this end, the ancient Greeks enforced a set of laws (nomoi) that applied equally to all citizens, de-emphasizing both kinship ties and differences between classes — which brings me to another point I may elaborate in more detain in another post: the aristocratic individualism of I-Es contained a democratizing impulse.

In the creation of city-states, and the subsequent democratization of these polities, particularly in Athens, we see an egalitarian impulse emerging out of the aristocratic war band and the prior aristocratic governments of ancient Greece when a council of aristocratic elders, without input from the lowers classes, was in charge. It is not that the old aristocratic values were devalued; rather, these values trickled downwards to some degree. The defense of the city, and warfare generally, would no longer be reserved for privileged aristocrats but would become the responsibility of hoplite armies manned by free farmers. Heroic excellence in warfare would no longer consist in the individual feats of aristocrats but in the capacity of individual hoplites to fight in unison and never abandon their comrades in arms.

The democratization of the city-states from Solon (b. 630 BC) to Cleisthenes (b. 570 BC) to Pericles (495–429 BC), the creation of popular assemblies, were associated with the adoption of hoplite warfare, starting in the mid-seventh century, the abolition of debt slavery, the securing of property rights by small landowners, and the creation of an all-embracing legal code. This unity of purpose was taken to its logical conclusion in the ideal city state imagined by the character of Socrates in Plato’s Republic, “Our aim in founding the city was not to give especial happiness to one class, but as far as possible to the city as a whole”.

Individualism and Ethnocentrism Among Romans

The ethnocentrism of the Greeks beyond their city-states should also be recognized. The ancient Greeks came to envision themselves as part of a wider Panhellenic world in which they perceived themselves as ethnically distinct precisely in lieu of their individualistic spirit, which they consciously contrasted to the “slavish” spirit of the Asians. As Lynette Mitchell observes in Panhellenism and the Barbarian in Archaic and Classical Greece (2007), “there was in antiquity a sense of Panhellenism”. Panhellenism was “closely associated with Greek identity”. While this unity was ideological, rather than politically actual, weakened by endless quarrels between city-states, the Greeks contrasted their citizen politics with the despotic government of the Persians.

Europeans, however, would have to wait for the Romans to start witnessing a strong common identity beyond the city.

We must look for this aristocratic individualist ethos in the “non-despotic government” the Romans created, their republican institutions. This was a government in which aristocratic patrician families contested and shared power in the senate, which would eventually expand to include representative bodies, tribunes, for non-aristocratic plebeians with wealth, towards a separation of powers, between the senate of the patricians and the tribunes of the plebs, along with two consults from each body elected with executive power. The I-E aptitude for openness and social mobility was reflected in the rise of plebeian tribunes and the eventual acceptance of marriage between patricians and plebs. It was also reflected in the gradual incorporation of non-Romans, or Italians, into Roman political institutions. As MacDonald writes,

Instead of completely destroying the elites of conquered peoples, Rome often absorbed them, granting them at first partial, and later full, citizenship. The result was to bind ‘the diverse Italian peoples into a single nation'” (80).

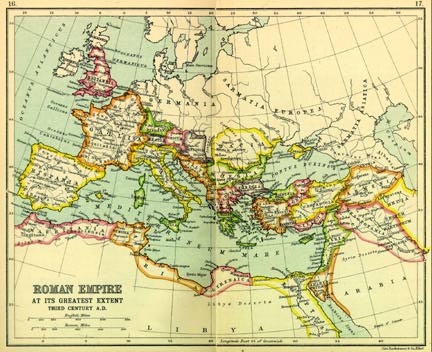

Unlike the Greeks who restricted citizenship to free born city inhabitants, the Romans extended their citizenship across the Italian peninsula, after the Social War (91–88 BC), and across the Empire, when the entire free population of the Empire was granted citizenship in AD 212. MacDonald believes that this openness beyond Rome and beyond Italian ethnicity “resulted in Rome losing its ethnic homogeneity” (84). He cites Tenney Frank’s argument (1916) that Rome’s decline was a product of losing its vital racial identity as Italians become mixed with very heavy doses of “Oriental blood in their veins”. He believes that the Roman I-E strategy of incorporating talent into their groupings worked so long as “the incorporated peoples were closely related to the original founding stock”.

I am not sure if by “closely related” MacDonald means only the Latins; in any case, I see the forging of all Italians “into a single nation” as a very successful group evolutionary strategy in Rome’s expansionary drive against intense competition from multiple cultures and civilizations in the Mediterranean world. Similarly to the Greeks, the Roman-Italians retained a very strong sense of ethnic national identity throughout their history.

It is important to keep in mind that Italian citizenship came very late in Roman history, some five centuries after Rome began to rise. We should avoid conceding any points to the erroneous and politically motivated claim by multiculturalists that the Roman Empire was a legally sanctioned “multiracial state” after citizenship was granted to free citizens in the Empire. This is another common trope used by cultural Marxists to create an image of the West as a civilization long working towards the creation of a universal race-mixed humanity. Philippe Nemo, under a chapter titled, “Invention of Universal Law in the Multiethnic Roman State,” want us to think that “the Romans revolutionized our understanding of man and the human person” in promulgating citizenship regardless of ethnicity. But I agree with the Israeli nationalist Azar Gat that ethnicity remained a very important marker for ancient empires generally, no less an important component of their makeup than domination by social elites over a tax-paying peasantry or slave force. “Almost universally they were either overtly or tacitly the empires of a particular people or ethnos.”

It should be added that Romans/Latins were so reluctant to grant citizenship to outsiders that it took a full-scale civil war, the Social War, for them to do so, even though Italians generally had long been fighting on their side helping them create the empire. Gat neglects to mention that all the residents of Italy (except the Etruscans, whose status as an Indo-European people remains uncertain) were members of the European genetic family. Let’s not forget how late in Rome’s history, AD 212, the free population of the empire was given citizenship status, and that the acquisition of citizenship came in graduated levels with promises of further rights with increased assimilation. Right until the end, not all citizens had the same rights, with Romans and Italians generally enjoying a higher status.Moreover, as Gat recognizes, Romanization was largely successful in the Western half of the empire, in Italy, Gaul, and Iberia, all of which were Indo-European in race, whereas the Eastern Empire consisted of an upper Hellenistic crust combined with a mass of Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Judaic, Persian, and Assyrian peoples following their ancient ways, virtually untouched by Roman culture. The process of Romanization and expansion of citizenship was effective only in the Western (Indo-European) half of the Empire, where the inhabitants were White; whereas in the East it had superficial effects, although the Jews who promoted Christianity were “Hellenistic” Jews. This is the conclusion reached in Warwick Ball’s book, Rome in the East (2000). Roman rule in the regions of Syria, Jordan, and northern Iraq was “a story of the East more than of the West.” Similarly, George Mousourakis writes of “a single nation and uniform culture” developing only in the Italian Peninsula as a result of the extension of citizenship, or the Romanization of Italian residents. Perhaps we can also question Tenney Frank’s argument about the heavy presence of Oriental blood in Italy. According to David Noy, free overseas immigrants in Rome — never mind the Italian peninsula at large — might have made up 5% of the population at the height of the empire, which is not to deny Orientalist elements among the enslaved population.

For these reasons, I would hesitate to say that the I-E strategy of openness dissolved the natural ethnocentrism of Italians and Europeans generally. Their aristocratic individualism should be seen as a more efficient and rational ethnocentric strategy re-directed towards a higher level of national and racial unity, without diluting in-group feelings at the family level. It was only at the level of clans and tribes that the Greeks and the Romans diluted in-group kinship tendencies when it came to the conduct of political affairs. In Rome, the Senate worked as a political body mediating the influence of families in politics, not eliminating kinship patron-client relations at the level of families, but minimizing their impact at the level of politics. The Senate was a political institution within which elected members (backed by their extended families and patron-client connections) acted in the name of Rome even as they competed intensively with each other for the spoils of office holding.

It has indeed become clearer to me, after thinking about MacDonald’s contrast between kinship oriented and individualist cultures, why the East was entrapped to despotic forms of government. Rather than viewing this government as a purely ideological choice, it can be argued that the prevalence of despotism in the East was due to the prevalence of kinship ties in the running of governments and the consequent inability of Eastern elites to think about higher forms of identity in the way the Greeks and Romans did. Eastern empires were highly nepotistic, with rulers using the state to expand their kinship networks, favoring relatives while behaving in a predatory way against rival ethnic-tribal groups, without a sense of city-state or national unity, and without the ability to generate loyalty among inhabitants or members belonging to other kinship groups. The historian Jacob Burckhardt once observed about the Muslim caliphates that “despite an occasionally very lively feeling for one’s home region which attaches to localities and customs, there is an utter lack of patriotism, i.e., enthusiasm for the totality of a people or a state (there is not even a word for ‘patriotism’)”. Burckhardt does not say anything about kinship, but it seems reasonable to infer that the strong kinship ties that prevailed in the East made it very difficult to forge a common identity beyond these ties.

What ultimately allowed the Romans to defeat the Semitic Carthaginian empire, thereby securing the continuation of Western civilization, was their ability, in the words of Victor Davis Hanson, to “improve upon the Greek ideal of civic government through its unique idea of nationhood and its attendant corollary of allowing autonomy to its Latin-speaking allies, with both full and partial citizenship to residents of other Italian communities”. This form of civic identity among Italians was the main reason Rome was able, as MacDonald observes, “to command 730,000 infantry and 72,7000 cavalrymen when it entered the First Punic War” and to sustain major defeats in the early stages of the Second Punic War without losing the loyalty of its Italian allies and the ability to marshal huge armies.

We will see in our review of future chapters that what I have said above is not inconsistent with MacDonald’s thesis but relies on his own observations that a fundamental by-product of individualism is the formation of ingroups that are based on reputation and moral norms rather than on kinship. We will see that the same Christian Europe that pushed further the breakdown of kin-based clans, cousin marriage and polygamy, created a powerful moral community across Europe: Christendom. The point I am making now is that we should also see the ancient Greek city-states and the idea of Romanitas (or Romanness) as attempts to forge broader ingroup unities without relying solely on kinship relations. It is no accident that Europe would eventually give birth to the formation of the most powerful nation-states in the world, capable of fighting ferociously with each other while dominating the disorganized, clannish, despotic non-White world.

I wonder if the individual sovereignty afforded by Bitcoin will make it the Corded Ware of our epoch?

That Bitcoin affords individual sovereignty is debatable. Future archeologists will sorely miss digging up ceramics to understand what became of us.

(Mod. Note: Thanks, Trenchant. Fixed!)

The author is truly a magnificent fellow amongst our people. I have written reviews of his book and consider him a giant among men. We are truly blessed have such an outstanding fellow fellow.

Just before getting out of bed I thought of how Euro civilization has fallen. Children no longer study about our accomplishments. They come home from school and the lying Tube further indoctrinates them. Then, they go into cyberspace. There they encounter anti-majority indoctrination and queer messages from Apple News and most other MSM sources. The grow up and notice that females are now the majority in universities and a large percentage jump -like dogs- into recreational sex (losing much of their former value). They feel that more than one child is a burden. Males fear marring them. In fact, marriage, in all probability, will overall disappear. Books are being replaced in libraries by digital items. It use to be that you could judge a home’s intellectual spheres by their libraries. How many homes even have libraries? Scholars self censor. Very few are as brave as the author of this article. I take my hat off to him. May he live a hundred years.

I hold that dogs have maintained their value, but I’m partial.

First and foremost, PLEASE stop talking about physical phenotypes until we’ve shifted the domain of discourse to be all about the evolution of heritable individualism!

Individualism is meta-moral because it recognizes that individuals of integrity differ in their morals and therefore in their preferred “moral communities”. This is what makes our race superior and provides us with the morale to fight and win. Until we’ve vanquished our enemies, we must focus only on this because it is essential to unifying individuals of integrity in a cohesive war machine. Unlike other races, that unconsciously war (engage in group conflict) as a primary strategy for mere supremacy, we are Moral Animals that only temporarily abrogate our individual sovereignty to a power structure for the purpose of military supremacy. At present, we must suppress anyone who in any way denigrates our heritable individualism and promote only those who recognize it as the reason our race is not just morally superior to other races, but is biologically-meta-morally superior to other races.

This is the rock upon which we can build an invincible military.

Second, it is no small error to adopt the “10,000 year explosion” paradigm for the evolution of individualism, just as it is very dangerous to attribute this evolution to recent historical practices. The “coincidence” between the R1b and I1 haplotype cultures of individual integrity should be a clue as to why the “10,000 year explosion” paradigm the wrong ansatz. You need to address this “coincidence”. Failure to do so is a failure to understand the evolutionary pressures that created us which denies us the knowledge we need for eugenics. If you think eugenics is secondary to survival of the white race, you’ve got the cart before the horse again. Get this straight, folks: The Moral Animal is moral only to the extent that he cultures that which he finds good. When I say “cultures” you need to toss off the semantic baggage imposed on us by alien cultures and remember deep in your being that agriCULTURE and CULTURE have the same object: Furtherance of Creation.

Culture is artificial selection or it is nothing of crucial importance.

Finally, although I’ve stated many times (and argued I think cogently for) my hypothesis of the root culture of I1 and R1b individualism to be coevolution with wolves as a replacement individual reliance on human hunting groups (and seem to have gotten nowhere with the intellectual leadership of white nationalists) we can differ on this and still agree that something caused east Asians and western Eurasians to a cultural divergence that has had biological ramificiations. Understanding this cause is critical to understanding ourselves and east Asians.

” the reason our race is not just morally superior to other races,”

Apples and oranges . Different cultures/races would require different moral codes to attain the same goal ( assuming the “same goal” is possible ) . Your “morally superior” assertion would be valid only for judging various moral code sets for the same culture/race in attaining the same goal . In other words , a superior moral code set for one group would not usually be a superior set for a different group to attain the same goal .

Science discovered that Whites have IQ supremacy compared to most other races . However , the aggregate average level of White political intelligence is very low compared to the average White IQ .

Morals are nothing more than at most an important accessory to facilitate the attainment of objectives . Establishing a particular moral code set is not the ultimate goal in life except for Christians whom claim to be in possession of a universal moral code set that is valid for all peoples and for all objectives ( pure religious dogma that typically ignores empirical reality ) .

The ultimate goal in life is to have fun ( that is , to secure enjoyments or pleasures ) where “fun” is most likely not exactly the same thing for any different culture/race ; so that an at least slightly different superior moral code set would be appropriate for each distinct group .

“We have made Italy. Now we must make Italians.”

– Massimo D’Azeglio.

Italy apparently boasts the highest human biodiversity of any European country.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24607994/