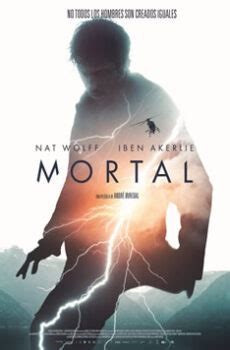

Review of Andre Øvredal’s “Mortal” (2020)

Mortal is a 2020 English-language Norwegian film based on Norse mythology co-written and directed by André Øvredal (interviewed here). It begins with a strange traveler stumbling out of the wood under a dark gray clouded sky as the early evening sets in the land of the midnight sun. He can’t travel as a man among the ruins, unnoticed and unmolested. A marginal in the modern world, it isn’t long before he crosses the path of a degenerate youth of the type dragging down Scandinavia. For the stranger, he’s just a dumb punk who can’t handle the request of “leave me alone.” The wiggers yell at him from their auto, and the stranger warns, “If you touch me, you will burn.” It only takes a second. . .

There’s a fire rising from within him but there’s no control. It’s unclear whether our protagonist is harnessing this power from some unseen inner core or it’s simply an uninhibited force using him as it’s instrument. The only known catalyst for the onset of these strange powers seems to be his raw unchecked emotions. The pain overtakes him. His chest heaves. His skin burns, cracking and peeling…

The scene shifts to Christine, a sweet-faced, yet seemingly hapless therapist who works for the state. Hired recently, she’s already failed at the starting line and lost a client to suicide. We’re introduced to her through the condolences of her supervisor. “No one’s blaming you. Not the parents, no one. . . . Unfortunately, these things happen. Therapy doesn’t always help.”

Blaming herself, Christine cries to her friend. State-sponsored therapists are the last line of defense against suicides. They have the essential authority when measures have to be taken to institutionalize potential suicides before they self-harm. This is often against the will of their patients. She blames herself, insisting that all of the signals were there, but she simply didn’t want to believe it. One could surmise that she feels the guilt of someone who didn’t prevent a tragedy because they didn’t want to be bothered.

She takes an incoming call. Her services are now required by the police. After regaining her composure, she makes her way toward a small Norwegian town at the foot of a misty hilltop covered in coniferous trees. A dark primal green still rules this land, never out of sight. Her counterpart in law enforcement greets her in the lobby. Henrik is an old veteran of the force with a hard-featured Aryan face and two perennially calm ice blue eyes that betray the kind of deep thoughtfulness that comes with decades of life experience predicting the actions and outcomes of mankind’s most aberrant and abominable.

He informs her they have in custody one Eric Bergland, the Norwegian-American backpacker looking for distant relations who’d gone missing three years ago after a fire at a farm in Årdal that left five dead. He’s not been seen or heard from since then, and he’s wanted for questioning. The Crime Unit is on its way, and time is of the essence to get Bergland to speak about the freshly roasted corpse he left on the roadside, the corpse of one young legend-in-his-own-mind who had an entire lifetime of perpetual adolescence ahead of him.

Nervously she approaches Bergland and begins an interview with the passable English she possesses. She’s unsure whether or not he’s even competent for the conversation. Slowly he begins to explain. To Christine’s surprise he wasn’t even sure if everyone had died in the blaze at the farmhouse he was initially sought for. As he comes to the realization of the amount of death he’s caused, a tear runs down his face. The scruffy backpacker seems overtaken by anxiety as the young therapist watches the water bubble from the glass of water routinely given to those being questioned. Reaching a hand forward, palm down, he begins to raise droplets of the liquid to his hand, defying gravity. The room is suddenly supercharged with electrical energy whose static causes strands of his interlocutor’s blonde hair to stand on end.

Øvredal’s Norway is a primal land of low magic—an archaic elementalism that Eric does not understand. He heats up from the inside like a dynamo. With the breadth of his powers now becoming apparent, the cavalry swoops in. The United States has sent its most highly over-esteemed Third-World Janissary as the representative of Uncle Sam on earth.

The casting in Øvredal’s films is free of affirmative action hires. Those few lesser-thans who make their appearance serve as characters who are typically contemptible and at best pathetically naïve. There are no Black Vikings hiding behind a megalith—traditional horror film rules still apply. Here the role of America’s hired muscle is an Indian woman with a British accent — someone alien to a wayward American. Though she acts with the authority of the US government none among us would call her a fellow American.

The dusky-hued face of life, liberty and the pursuit of global hegemony.

The character of Christine, though having only just met the man, fulfills her natural feminine role by pacifying the rage and anxiety in this lost soul. The strength of her character isn’t in the way she reacts to danger or the dialogue she has in this supporting role. It’s in the power to bring out growth in a man and maintain a shelter in the storm. A feminine role that complements the masculine rather than challenges it. This portrayal of the natural aesthetic polarity of the sexes is refreshing when one considers the overabundance of obligatory “battle broads” that Tinsel Town’s trash heap has been shelling out.

Throughout his other films, the special effects seep into the environment and seamlessly flow through their interactions with other characters and their surroundings. It is a characteristic of the Norwegian filmmaker to never portray a character with utter disbelief. Surprise? Yes. Terror? Often. But none in his plots elicit hysterical denial. They believe what they see. They don’t understand it, but they fear it.

Eventually Eric has no choice but to run to the only human offering him comfort in the years that have passed since he entered the forest.

Now seeking help, the little group pulls up to a river dock to cross the waterway. “I love ferries. It’s like taking a break from the real world for a few minutes,” Christine states matter-of-factly to Eric. It’s not a dreamy or romantic tone, but a statement of principle.

They learn shortly that the noose is tightening. Eric is having visions that put him in a passive state with a serene dreamy look on his face. He’s seeing things beyond our world and time. Different worlds. . . and a great tree. The most beautiful tree that fills the horizon. Yggdrasil? Christine wonders if he’s a messiah of some kind.

One of many depictions of Yggdrasil, the Tree of Life in Norse Mythology

Hardanger Bridge is the busiest bridge in all of Norway. It lies between Bergen and Oslo, the country’s largest cities. A confrontation during rush hour there means the whole world is watching. It isn’t just the traffic that will grind to a halt that concerns them—everyone will see the videos they share on social media. This, above all is what the government creep of alphabet soup agencies is trying to avoid. He cannot be allowed to manifest his powers in a major city.

But there’s no denying it now. The U.S. sent their ‘girl Friday’ with a license to kill. The condescending Third Worlder knows the national security risk. But the state is always weaker than religion. She makes the phone call, regardless. “Imagine in a few days when people realize what he represents … or what he doesn’t represent. Imagine Christians, Muslims—everyone who believes in a god. Suddenly a god-like human proves they are all wrong. He doesn’t represent any of them. What happens then?” She ends by concluding that a final solution has been determined. “I’ll make sure it happens.” We don’t need to hear her orders to know what she’s planning next.

They try to stop him at the center of the bridge. A Norwegian hasn’t earned himself this much attention from the police services since Breivik. The sky goes black as his passions seize him. Eric is cornered. This time the full spectrum of the titanic abilities he wields is on display. There’s no denying it now.

By now the origins of his god-like destruction are obvious. Taken again under the wing of the state, they study the confused young superbeing. An ethereal call draws Eric into the orbit of the farmhouse inhabited by his ancestors, the source of whatever the polar force that has possessed him is radiating from. Gaining passage to the subterranean causeway deep within a cold dark earth, he searches among the cellar roots to find that which is most sacred and long forgotten by many. The spiritual origins of this great Northern people.

Mortal has a serious and respectable tone. It would appear to be an attempt to rescue Norse mythology from Hollywood depictions such as the popcorn-funded hipster kitsch of JJ Abrams’ latest abortions or the ominous tenor of Ari Aster’s Midsommar (2019) – a fascinating film in its own right but secular in its aesthetics. This director has proven himself as one to watch out for as he fluctuates between larger budget studio films and his more personal projects when the profits from the former are used to bring his intimate creations to life.

Very interesting film review.

I am just wondering how many Scandinavians will actually be able to decipher the film’s symbolism and understand its importance in terms of their own current circumstances as well as the potential for a future social revival.

Thank you for helping to increase awareness of Norse mythology.

In my view, the war on Europeans (and subsequently other pagans) started with religion and — if we survive long enough — our recovery will also be via religion; an evolved form of Odinism in the case of Europeans, wherever they might now live on Earth.

I’ve seen the move recently and this review is spot on. My only complaint with the movie is that a black-haired, half-Jew who was “brought up culturally Jewish” (Nat Wolff) was cast as Eric. Given what Eric’s lineage is eventually revealed to be, casting Nat Wolff is doubly ridiculous. I wonder if the Golden One can act. Now that would have been a good match.

I haven’t read the whole article/review because the author was going into so much detail that I thought it will give away the plot. Anyway, I agree with you Casper, I did not like a bit the casting of a Semitic looking bloke. That already put me off and frankly ruined the whole thing. Why the Hell the director did not cast a blond man, a real Scandinavian as Eric Bergland? I shall not waste time watching this film.

Thinking from the perspective of https://theapolloniantransmission.com/ I wonder if this whole film is another case of Jews stealthy stealing our culture, our gods, our power, and our women (as represented by the female star).

One thing for sure, casing a Jew as Thor was no accident.

You might note that midsommars director is also Jewish. This fact gives a new dimension to his depiction of Nordic paganism I should think.

Looks like the typical multi-cult garbage to me..

Yes, I agree with you, as I said before, casting a bloody Jew (and a very Semitic looking one) as a Nordic/Scandinavian man is an insult and a vile thing to do. I will not waste a minute watching that crap.