Sholem Aleichem’s Curse: Anti-Russian Themes in Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate

Jewish diaspora fiction has always been problematic for me, largely because the authors I have read will either champion an overtly Jewish perspective without taking competing gentile ones into account (Saul Bellow, Chaim Potok, Isaac Bashevis Singer) or perceive themselves as ethnic outsiders and attempt to subvert gentile societies which are, of course, inherently bad (Franz Kafka, Philip Roth, Nathaniel West). As with anything, the quality varies, and there is much more to the crude categorizing I resort to above. Arthur Koestler’s excellent Darkness at Noon bucks the trend, as does Stanislaw Lem’s Polaris in the science fiction genre. And what to make of Ayn Rand? But if I had to distill my feelings for Jewish diaspora fiction in one sentence, this, unfortunately, would have to be it.

These two author types rely on the spurious Jew Good/Gentile Bad dichotomy which is essentially opposite sides of the same shekel, so to speak. The classic example, of course, is Sholem Aleichem’s Fiddler on the Roof (and I am referring to the popular musical and film adaptations and not so much to Aleichem’s Teyve the Milkman stories). In Fiddler, Jews are portrayed as charmingly innocent salt-of-the-Earth types who are at best heroic and honorable, and, at worst, eccentric in their picadilloes. In such a worldview, the anti-Jewish wrath of gentiles resembles natural disasters in that they attack without warning or reason, and leave devastation in their wake. Unlike natural disasters, however, this is the work of Man, and so can be ascribed to Evil and therefore dealt with. That Jews commit deadly sins of their own which cause equal devastation among the gentiles never enters the plotlines of these stories. Neither does any good resulting from self-identifying, nationalistic non-Jews. As a result, much of Jewish diaspora fiction amounts to little more than libel of the goyim.

Very few Jewish fiction authors can overcome this dichotomy. Better they forget their Jewishness and write simply to enthrall gentiles, or keep their Jewish identity and write strictly for Jews, preferably in Hebrew.

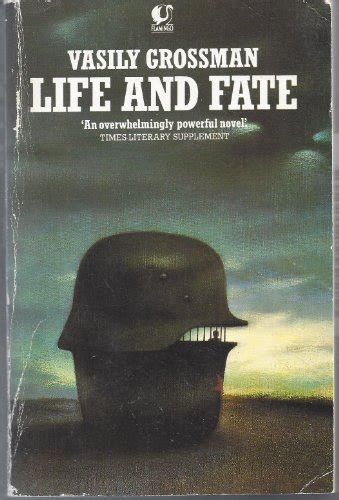

Jewish author Vasily Grossman’s epic novel Life and Fate fails to escape this dichotomy and yet retains a great deal of value for its realistic depiction of the enforced conformity of mid-century Soviet life. It also deserves note for its narrative reporting of the Battle of Stalingrad and depiction of the Soviet gulag. Completed in 1960 and suppressed by the KGB, it was smuggled to the West and published in 1980 to instant acclaim, sixteen years after the author’s death. Fortunately, it avoids the trap of modernism, and weaves its many plots and subplots together in a complex yet comprehensible fashion. Stream of consciousness, fragmentation, Freudianism, nonlinear storytelling, and other postmodern tricks are thankfully eschewed. So is all hint of degeneracy. This makes Life and Fate one of the breeziest long novels I have ever read. That it is uneven, tendentious, strident, overpopulated, and lacking the majestic story arc worthy of its 870-odd pages keeps it from the ranks of great novels. It also tells almost as much as it shows, which sucks much of the power out of the story. For example, when one of our female protagonists decides to toss over her lover (a brilliant tank commander) for her ex-husband (a disgraced commissar languishing in the Lubyanka prison), we learn about it after the fact from the narrator. But we don’t get to see it. Grossman glosses over several important plot points in the same manner.

Even worse, when the author speaks as a Jew—directly to his readership, which he does several times—he’s little better than a bad poet lecturing us on the evils of anti-Semitism. His gnashing of teeth over the poor, noble-hearted Jews being sent to their deaths are as manipulative as anything in Schindler’s List. For example, upon entering a German concentration camp, the saintlike Sofya Levinton realizes she could save herself because she has medical training, but chooses not to. She opts instead to remain by the side of a little orphan boy named David as they tragically get gassed together.

From Part Two, Chapter 46:

Death was standing there, as huge as the sky, watching while little David walked towards him on his little legs. All around him there was nothing but music, and he couldn’t cling to it or even batter his head against it.

As for the cocoon, it had no wings, no paws, no antennae, no eyes; it just lay there in its little box, stupidly trustful, waiting.

David was a Jew…

Grossman, editorializing transparently through his narration, is also quick to dishonestly condemn fascism and Nazism, while failing to condemn the demonstrably greater evils of communism and Bolshevism just as directly. (To be fair, Grossman does do this, but through character and plot over hundreds of pages—that is, appropriately, and never in the didactic manner with which he dismisses fascism.) For example, in Part One, Chapter 2, he writes the following series of lies:

National Socialism had created as new type of political criminal: criminals who had not committed a crime. [Tell that to A.I. Vipper, the prosecutor of the 1913 Menahem Beilis trial who was shipped off to a concentration camp by the Bolsheviks in 1919 and never heard from again.]

The detainment of prisoners-of-war in a concentration camp for political prisoners was another innovation of fascism. [Apparently, Grossman had never heard of the Solovki prison camp, which was established in 1923 by the Soviets to detain perceived enemies of the newly formed Bolshevik state.]

Giving common criminals power over political prisoners was yet another innovation of National Socialism. [A falsehood repeatedly exposed in Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago. The Soviets were doing this as early as the 1920s, before the rise of National Socialism.]

Here is my favorite, from Part One, Chapter 42—lurid, hysterical, and impossible to refute:

If fascism should ever be fully assured of its final triumph, the world will choke in blood. If the day ever dawns when Fascism is without armed enemies, then its executioners will know no restraint: the greatest enemy of fascism is man.

Yet when Grossman forgets his Jewishness and gives us the nuts-and-bolts narrative of how the Soviets emerged victorious at Stalingrad, he’s first rate. He presents a splendid array of characters: from a true-believing commissar with a dark secret, to a skeptical and reticent tank commander, to a war-weary power station director, to a womanizing staff officer, to an independent-minded soldier fighting fearlessly in the rubble. His mastery of geography and scenery is complete as well, from the dusty Kalmyk steppes, to the dingy apartments of Kazan, to the demolished city blocks of Stalingrad. His sympathetic portrayals of German General Friedrich Paulus and other officers of the Wehrmacht while they were locked in deadly struggle over that nearly-conquered city were some of the most moving for me. And this all makes sense, given that Grossman was a war correspondent who was in Stalingrad and many other places during the fighting. For the war scenes of Life and Fate, he certainly wrote what he knew, and what we get is punchy, insightful, gripping historical fiction, which serves almost as much as a critique of the oppressive groupthink associated with communism as it does of the German invasion itself. But this is about half the novel.

Vasily Grossman with the Red Army in Schwerin, Germany, 1945.

The other half, which is dominated by the drama surrounding Jewish physicist Viktor Shtrum and his family, focuses on Stalinism and how it tempts ethnic Russians to commit the twin sins of nationalism and anti-Semitism. This predictably evokes the stereotypically Jewish fear of the vengeful gentile so prevalent in Fiddler on the Roof and other diaspora works. And as translator Robert Chandler admits in the novel’s introduction, this makes Grossman a liar since the Russian pushback against Jewish dominance didn’t occur until the late 1940s and early 1950s—not as early as 1942 as Grossman depicts. Shtrum’s story also has little to do with the battle of Stalingrad, and could have been culled out of Life and Fate to constitute a completely different novel. As such, we’re left with a disjointed narrative which is much longer than it needs to be.

But this is one of the novel’s lesser flaws. Its greatest (and the one likely to be of most interest to Occidental Observer readers) is how Grossman, try as he might, cannot overcome Aleichem’s Curse. Gentiles remain tainted in Life and Fate. They are the source of all evil, while Jews maintain their existential innocence in the face of injustice and oppression.

In Grossman’s USSR, Jews never willingly identify as Jews. Instead, they are simply honest and industrious participants in the Soviet experiment. They self-identify only when they are betrayed by anti-Semitic gentiles who remind them of their Jewishness. This happens first by the Nazis, then by the Soviet leadership, and finally by ordinary Russians who, according to one Jewish character, enjoy not having to smell garlic now that all the Jews are gone. This, of course, is pure Judeophilic cant. Given the complicity of Jews in the bloodiest years of the Soviet Union as well as their well-documented ethnocentrism and xenophobia, this reviewer will never disbelieve that Jews are at all times keenly aware of themselves a distinct ethnic group—which is indeed why gentiles everywhere have anti-Jewish feelings to begin with.

Often in the novel we are reminded that Viktor Shtrum never once thought of himself as a Jew until he came face to face with Fascism. Part One, Chapter 18 is the (admittedly heartbreaking) text of Shtrum’s mother’s final letter to her son before being herded off to the camps, and in it she writes: “That morning I was reminded of what I’d forgotten during the years of the Soviet regime—that I was a Jew.”

This is the first key to Jewish innocence in Life and Fate. The second is that while Jews are pure Soviets, Russians are either Russians in Soviet clothing or they are willing to bow down when their co-ethnics exhibit such insidious nationalism. Of course, not all Russians in Life and Fate are like this—not Shtrum’s estranged wife Lyudmila, who’s mourning the loss of her son in battle; not her first husband Abarchuk, who’s languishing in a gulag; not Mostovskoy, an old Bolshevik who’s about to stage a hopeless rebellion in a German prison camp; and certainly not Marya Ivanovna, the wife of Shtrum’s colleague for whom he has deep feelings. Grossman handles all of these characters (and others) impeccably. What isn’t impeccable is how he depicts only the villainous, the cowardly, and the ignorant as expressing the gentile nationalism which he as a Jew finds so threatening.

Here is Getmanov, a calculating and menacing commissar complaining about affirmative action (Part One, Chapter 52):

A frown suddenly appeared on his face. ‘Quite frankly,’ he went on angrily, ‘all this makes me want to vomit. In the name of the friendship of nations we keep sacrificing the Russians. A member of a national minority barely needs to know the alphabet to be appointed a people’s commissar, while our Ivan, no matter if he’s a genius, has to “yield place to the minorities”. The great Russian people’s becoming a national minority itself. I’m all for the friendship of nations, but not on these terms. I’m sick of it!’

Here is Sokolov, Shtrum’s colleague (and Marya Ivanovna’s husband) who ultimately fails to stand by Shtrum when he’s about to be arrested for anti-Soviet thoughtcrimes (Part One, Chapter 64):

‘Allow me to love Tolstoy—and not only because of what he wrote about the Tartars. We Russians, for some reason, are never allowed to be proud of our own people. And if we show such pride, we’re immediately taken for members of the Black Hundreds.’

It should be noted that this speech occurs in a conversation with a wholly sympathetic Tartar named Karimov who calls for the banning of Dostoevsky because “[a] great writer in this country has no right to persecute foreigners, to despise Poles and Tartars, Jews, Armenians and Chuvash.”

Here is the internal monologue of tank commander Novikov on the nationalistic Russian apparatchiks who force him to promote Russians over non-Russians (Part Two, Chapter 4):

… his superiors had always been men who were ignorant of the calibres of different guns, men who were unable to read without mistakes a speech that had been written for them by someone else, men who were incapable of making sense of a map or even of speaking proper Russian. Why had he had to report to them?

And here is the internal monologue of Lieutenant Bach, a well-meaning and thoughtful German officer who’s warming to the idea of the Final Solution (Part Two, Chapter 11):

The law that determines the birth of a nation-state is something miraculous and wonderful. A state is a living unity; it alone has the power to express what is most precious, what is truly immortal in millions of people—a German character, a German hearth, a German will, a German spirit of sacrifice.

And speaking of Germans, who can forget the gratuitous chapter Grossman includes on the young Adolf Eichmann who was sidelined into the Nazi Party because he simply wasn’t smart or talented enough to compete with Jews for work or for acceptance into universities? Such people Grossman summarily condemns in Part Two, Chapter 31 as “fools, reactionaries and failures.”

The final key to Jewish innocence in Life and Fate is that there are no Jewish villains. Grossman does absolutely no Jewish soul-searching. Yes, Genrikh Yogoda gets mentioned a few times as a bugbear of the Great Terror from the 1930s. But he is never outed as a Jew. Grossman (to his credit) discusses terror famines, dekulakization, and other Soviet atrocities in his text, but never does he even hint of Jewish culpability in these crimes. The closest he gets is stating in Part Two, Chapter 31 that “during the epoch of revolutionary struggle, many of the most important revolutionary leaders were Jews.” That’s not enough.

In Life and Fate, Jews are portrayed as victims more often than not. For example, a Jewish fighter pilot who gets harassed by an anti-Semitic comrade ultimately gets shot down. Rubin, a friend of Abarchuk’s, gets murdered in the gulag—and having read Chapter 20 of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s 200 Years Together, it’s hard to believe that Jews were murdered as often as gentiles in similar circumstances. Further, Shtrum’s junior colleagues, all of whom are smart, competent, and Jewish, fail to get promotions for dubious reasons.

Meanwhile, Shtrum is portrayed as downright sublime as he solves an important problem of theoretical physics. What lands him in trouble with his narrow-minded superiors is how he refuses to renounce Einstein and how he speaks of science in Part Two, Chapter 6 “as though it were a religion, an expression of man’s aspiration towards the divine.” He rejects the Party understanding of his field and instead insists that he keep his mind free from dogma. And when such scandalous individualism puts him on the brink of arrest, not one gentile colleague stands by him.

Ultimately, Vasily Grossman wishes to impress upon his readers that ethnonationalism is bad and that Jews would never indulge in a such a sin. Instead, we must worship individualism, as he states plainly in Part One, Chapter 53:

Human groupings have one main purpose: to assert everyone’s right to be different, to be special, to think, to feel and live in his or her own way. People join together in order to win or defend this right. But this is where a terrible, fateful error is born: the belief that these groupings in the name of a race, a God, a party or a State are the very purpose of life and not simply a means to an end. No! the only true and lasting meaning of the struggle for life lies in the individual, in his modest peculiarities and in his right to these peculiarities.

Yes. This is how Jews like their gentiles: atomized, isolated, and unprotected from predatory minority groups—such as the Jews—who have no intention of relinquishing their common identity and agenda. If Grossman had addressed this fatal flaw of the Jews as well, his novel may have achieved greatness. But that would have required reversing Aleichem’s Curse and transcending the Jew Good/Gentile Bad dichotomy which defines so much Jewish diaspora fiction, something Grossman was unfortunately not strong enough to do. (He was strong enough to defy the Soviet authorities, but not this.) This kind of overt political messaging also has nothing to do with the Battle of Stalingrad and reinforces my point that Life and Fate would have been better as two novels: one about the war and the other about Viktor Shtrum’s struggles against the Soviet Machine. Further, the latent anti-Russianness of the latter undercuts the accuracy of former since, as Solzhenitsyn pointed out in Chapter 19 of 200 Years Together, calls to Russian nationalism during the darkest days of the war were what helped the Russian people ultimately defeat the Germans.

There is much that is worthy about Life and Fate. Aside from its substantial literary qualities, it pre-dated The Gulag Archipelago by over a decade in its unveiling of the Soviet Union’s horrific crimes. It also superbly portrays the communist republic’s oppressive cultural atmosphere. The KGB had good reason to suppress Life and Fate, since the book did speak truth to power at a time when such an act could prove lethal for an author. The problem, however, is that we only get half the truth from Grossman. Sadly, he’s too much of a Jew to give us anything more.

Vaseliney Gross Man. What a greasy character. Under President Putin, the government is financing the construction of Orthodox churches and chapels throughout the Federation. National attendance is ~ 15 to 20 per cent now. But it is increasing. Within Putin’s ministerial circle and power players, he had specified that only those who were believers in the Church would be allowed to serve. Maria Zakharova, information chief for Foreign Ministry speaks occasionally of her religious devotion.

While this seems a tangential subject, in actuality it is not. Those that are accepting of a religious and spiritual Reality are more likely to speak truth and act concomitantly to the tenets of the Faith. Orthodoxy, my native religion, is the authentic prototype with the only Christian pedigree. A fuller appreciation and understanding of Orthodoxy is found it is full style name, Eastern Orthodoxy. Within, and like the Catheter Church of the West, it embraces mysticism and the metaphysical in none space and time constructs. There are not to be found the legalistic lawyered layers of laws and free floating concrete representations, derived from the influences of the Roman Empire.

And anyway, isn’t influence supported to flow from the religion to the state?? Like all Western religions, this one and the thousands of spare parts Protest Ants sects and cults, seem to move with the stock market. Remember (guffaw) “folk masses” of the trendy sixties? A marketing program to get the “kids” interested in The Church Corporation. (TM).

That ‘Darkness At Noon’ hasn’t been made into a film is frustrating.

It’s the most simple, concise and original book one could read. It could also be done simply even on a stage, probably by high schoolers.

I can’t remember if the Old Bolshevik was a Jew, he looked like one in my head when I read it, but he was being persecuted by what I remember as a Russian.

Considering this, you’d think they’d be ten movie versions of this tale by now, with blacks, women and red Indian transgenders given starring roles on Netflix’s 2022 version.

They must find the moral of the story very subversive of their cause. Which as it’s basically “let us clever Jews, who have been civilised by your gentile, orderly Christian society, totally remake it in our intellectual image, and we will create for you a race of heartless barbarians and a nightmarish bloodbath”, you kinda get where they’re coming from.

EMICHO–

Yeah, and the years 1618 to 1648, the time of the Thirty Years’ War, represented a great episode in the saga of the civilizing, orderly Christian civilization. Among many of such.

So your point is the Christian Czarist empire of the 1800’s that shaped the future Bolsheviks wasn’t civilised because their was a war in another Christian empire 250 years previously?

That’s your great point? That’s devastating.

Religion may have have been one of very many different causes that kick-started the Thirty Years War, but any fool can see it was just like every other war then and now, political. If the Christian schism was the ONLY cause, why were the French fighting on the side of the prods? Maybe because it was really about power?

It was as much about religion as the war in Northern Ireland is about religion, even Wikipedia describes The Troubles accurately as an ‘ethno-nationalist’ conflict. So that was about power as well, or political, to say it another way.

The most religious Irish had nothing to do with it, the least, the greatest enthusiasts for the mayhem.

EMICHO–

My point is it’s foolish to persist in claiming everything which Judeo-Christians produce is good, true and beautiful–as you’ve actually said. That Thirty Years’ War WAS a religious war, Catholic powers versus Protestant. And, in that 17th Century, Europeans burned other Europeans over that Jew-created creed–including my townsman Giordano Bruno and my namesake the philosopher Lucilio Vanini. Galileo was threatened with burning because he espoused the Heliocentric view—scientific truth—and so recanted.

And how many women were burned as witches? Thousands, nicht wahr? And what about earlier religious violence like the crusade against the Albigensian “heretics” in France, Charlemagne’s forcible conversion of the Pagan Saxons, and the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre? The conflict in Ireland, where I long resided and whose history I studied, was set up by “transplantation” of British Protestants into Ulster, a deliberate policy of the anti-papist court in London.

But at the very least, you can’t characterize Christian society as characteristically “orderly” and also agree that a Thirty Years War happened. Even if, for the sake of argument, religion had nothing to do with it, the fact that such a savage conflict occurred shows that Judeo-Chr. hadn’t made Europe all that orderly.

I’ll say it as many times as I need to and am allowed to: Not Judeo-Chr. but Pagan Hellas and Pagan Rome made Europe great. And after a long nadir during an unchallenged reign of the Church, it was a rebirth of the Classical perspectives of Hellas and Rome, the Renaissance, that made Europe great again.

P.S. you say the Jews were civilized by orderly, gentile Chr. society. Wanna know where they really thrived? Islamic Spain (the most advanced part of Europe during Judeo-Chr.’s unchallenged reign). I’ve been looking for some time but still haven’t found evidence of Jewish conspiracies against their Islamic overlords. I’m not apologizing for the Jews, because they DO everything they’re accused of; but I’ve long suspected that the stupid Judeo-Chr. bias against them for being “Christ-killers” was what’s made them view us, Europeans, as the perennial enemy. (I’d appreciate it if anyone here can enlighten me on this point, and cite examples of Jewish subversion in Islamic societies.)

EMICHO–

CORRECTION: The British policy of settling mostly Scottish Protestants in Ulster (a kind of anti-Catholic population replacement some centuries back) is actually known as the “Plantation” of Ireland or Ulster, not “Transplantation.”

Well, I never thought I’d see the day when a bona fide white Nationalist would be so twisted by his hatred of Christianity, he’d state it’s our fault the Jews hate us. We’ve seen it all now.

Look, I felt bad for blethering on about some other book, (though it did get mentioned) do you feel no shame at all polluting every comments section with your neurotic hang-ups with Christianty? Where does it come from? Was a priest naughty with you as a lad?

The Mod has specifically stated we’ve to stop boring everyone with this garbage.

As for Ireland, maybe this will help: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plantations_of_Ireland

Understand? It was about POWER.

If it was just a religious thing, wouldn’t they just send over missionaries?

People use religion just like they use patriotism, racism, xenophobia, money, threats, fear, etc, as a means to an end. A way to galvanise the peasants.

If people weren’t warring over religion they’d just as quickly be warring over something else. It’s called politics. Sometimes they’ll just fight over the football team they support. It’s human nature.

Taking every old tragedy and using it to attack Christianity isn’t just dumb and boring, it’s actually retarded.

EMICHO–

In my short time in a Catholic parochial school I wasn’t messed with by any priest, though I could write a long essay about the psychological and physically violent abuse inflicted on small children by nuns, the actual teachers. HOWEVER, if I WERE a victim of priestly child-molesting, your mockery would surely be less than charitable.

Apropos of Christian child-molesting, it has of course been rife; and don’t say it’s a result of relatively recent Jewish corruption of Judeo-Christianity. It’s not: there’s much evidence of what losers, many of them homosexual, tend to do in the religious institutions in which they seek refuge from “the world.” Consider this from the 11th Century–the 1000s: https://www.americamagazine.org/issue/534/article/11th-century-scandal

As for Ireland again, the auctioneer who sold me my property there was Sinn Fein/IRA; and he told me much, including that the Troubles were ethno-national in nature. He was right, but only to a degree. Sectarianism has always been an essential element in the struggle, and so said Dr. Paul Badham of St. David’s University College, Wales, in “The Contribution of Religion to the Conflict in Northern Ireland.” Among other things, Badham wrote “….religion remains central because, without it, the two communities [Catholic and Protestant] would long have since merged.”

https://www.jstor.org/stable/20751203

Yes, the Jew-created religion has divided Europeans. Before that, in the whole Mediterranean world, the only serious conflict over religion involved–guess who? The Jews, who, unlike all other nations in the Roman Empire, fiercely opposed any association of their bigoted creed with other people’s religions. The Pagans were very tolerant: in temples around the Empire one found images of very many peoples’ Gods; and the Romans tended to identify their deities with those of other peoples, viewing them as the same deities under different names.

No surprise, the religion that Jews fashioned for the goyim came with the old Judaic exclusivity, the “We alone are right and everyone else is all wrong.” That kind of thing has led to numberless persecutions, burnings, conflicts from that between the ancient Catholics and the Arians (followers of Arius, who denied the Trinity) to the Irish Troubles.

I am shipping a car from the sixties out of California. The company is Montway, with the best reviews. The actual driving is sub-contracted to Veteran Transport LLC- the driver’s name is Yevgeny Tuchinsky. $959 for 537 miles.

NS Rubashov, on the jewish surname list [avotaynu]

You’ve reminded me I’ve not read it, and should. Looking online, I find this, in case you aren’t aware of this “new” version:

In print continually since 1940, Darkness at Noon has been translated into over 30 languages and is both a stirring novel and a classic anti-fascist text. What makes its popularity and tenacity even more remarkable is that all existing versions of Darkness at Noon are based on a hastily made English translation of the original German by a novice translator at the outbreak of World War II.

In 2015, Matthias Weßel stumbled across an entry in the archives of the Zurich Central Library that is a scholar’s dream: “Koestler, Arthur. Rubaschow: Roman. Typoskript, März 1940, 326 pages.” What he had found was Arthur Koestler’s original, complete German manuscript for what would become Darkness at Noon, thought to have been irrevocably lost in the turmoil of the war. With this stunning literary discovery, and a new English translation direct from the primary German manuscript, we can now for the first time read Darkness at Noon as Koestler wrote it.

That’s interesting I didn’t know that. I probably would read the new version, as it’s years since I read the original.

What I don’t understand is it’s description as a “classic anti-fascist text”. Unless it is just leftists describing everything the don’t like as ‘fascist’, I suppose that would make kinda make sense.

But the Old Bolshevik, I think the commenter above did get his name right, admits completely that the thug in front of him is the absolute 100% logical outcome of his hubristic, insane communist ideas. It’s not like he’s in denial, like modern communists, explaining the whole thing just wasn’t done right, and it was just bad luck it went off the rails and created mass slaughter, carried out by brain-dead happy butchers.

Yeah, the “fascist” part is weirdly amusing; I assume the people they hire to write copy for major publishers are either woke or pretend to be, hence “fascist” = anything my bosses don’t like. Intellectual integrity is not big in American publishing.

https://duckduckgo.com/?q=yevgeny+tuchinsky&t=brave&ia=web

Excellent review. I’ve had a remaindered copy of the first English language edition of Life and Fate on my shelf since around 1990, but have never read it. And I still have a couple of hundred other novels I want to read first. But maybe someday …