Emil Kirkegaard: Eulogy for Richard Lynn (1930-2023)

Editor’s note: This eulogy is from Emil Kirkegaard’s Substack. Richard Lynn was truly a pillar of the hereditarian thrust in psychology which is under assault or ignored by most academics now. I have cited him extensively in my writing. The good news is that researchers like Emil Kirkegaard are carrying on this tradition.

The last man of the old hereditarian triumvirate

For those interested in his personal history, you should read his 2020 autobiography Memoirs of a Dissident Psychologist (477 pages). It is one of the funniest nonfiction books I’ve read. For those looking for something shorter, there is his 2019 summary Reflections on Sixty-Eight Years of Research on Race and Intelligence. It’s worth quoting the introduction for his background for getting into the field:

I first encountered the question of race and intelligence sixty-eight years ago. This was in 1951 when I was a student reading psychology at Cambridge and attended Alice Heim’s lectures on intelligence. She told us that Blacks in the United States had a lower IQ than Whites and this was attributable to discrimination, which she subsequently asserted in her book (Heim, 1954) [1]. She also told us of the UNESCO (1951) [2] statement that “Available scientific knowledge provides no basis for believing that the groups of mankind differ in their innate capacity for intellectual and emotional development.” She did not tell us that this assertion was disputed by Sir Ronald Fisher (1951) [3], the Professor of Genetics at Cambridge, who wrote a dissent stating that evidence and everyday experience showed that human groups differ profoundly “in their innate capacity for intellectual and emotional development” and that “this problem is being obscured by entirely well-intentioned efforts to minimize the real differences that exist.”

Nor did Alice Heim tell us that Henry Garrett, the Professor of Psychology at Columbia University, had argued that genetic factors are largely responsible for the lower IQ of Blacks than of Whites (Garrett, 1945) [4] so I and my fellow students at Cambridge were not well-informed about the issue of race differences in intelligence and its causes. Alice Heim was giving us the mainstream position among social scientists in the 1950s and this remained largely unchallenged in the 1960s. I believe the only person who challenged it was Henry Garrett (1961) [5], who designated it “the equalitarian dogma”, but I did not know of him until much later. At this time I did not question the mainstream position among social scientists that Blacks and Whites have equal ability as my interest during these years was in personality and I was not thinking about intelligence.

It was in 1967 that I became interested in this issue. This came about when I moved to Ireland to take up a position as research professor at the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESIR) in Dublin. The purpose of the ESIR was to carry out research on the economic and social problems of Ireland and find policies that would help solve them. Foremost among these was that, at that time, Ireland was quite economically backward compared with Britain and I researched the literature to see what contribution I could make to this problem. It was not long before I discovered a study by John Macnamara (1966) [6] that reported that the IQ of Irish 12 year olds was 90, compared with 100 in Britain. It appeared that the low IQ was likely a significant cause of the Irish economic backwardness. I knew that intelligence was a determinant of earnings among individuals and that this was also true for groups. I knew of Cyril Burt’s (1937) [7] book The Backward Child, in which he showed that children in the boroughs of London had different IQs and that these were highly correlated across the boroughs with the earnings of adults. I knew that this had also been shown by Maller (1933) [8] in the boroughs of New York city. It seemed likely that the same would hold for nations and, in particular, for the economic backwardness of Ireland. This was how I came to formulate the theory that differences in intelligence are an important determinant of national per capita incomes that I was to publish later, in collaboration with Tatu Vanhanen, in IQ and the Wealth of Nations (Lynn and Vanhanen, 2002) [9].

As I thought about this in 1968, I decided it would be wise to check Macnamara’s study reporting the low Irish IQ. I asked two of my assistants, Ian Hart and Bernadette O’Sullivan, to carry out a further study and they did this by administering Cattell’s Culture Fair test to a sample in Dublin. They found their sample had an IQ of 88 compared with 100 in Britain (Hart and O’Sullivan, 1970) [10] and therefore closely similar to the IQ of 90 that Macnamara had reported.

Although this confirmed Macnamara’s study, it was a disconcerting result. I wondered whether it would be wise to publish my conclusion that the low IQ was a significant factor responsible for the economic backwardness of Ireland. I doubted whether this conclusion would be well received, particularly coming from an Englishman telling the Irish that they had a low IQ problem. Furthermore, it would raise the question of what policies could be adopted to solve the problem. These would be a set of eugenic policies that would raise the Irish IQ, such as the sterilization of the mentally retarded and incentives for graduates to have more children. Eugenic policies of this kind had been regarded as sensible by most informed people in the first half of the twentieth century but in the late 1960s they had begun to be repudiated. In many countries, eugenics societies closed themselves down or changed their names and that of their journals. In 1968, the British Eugenics Society ended the publication of its journal The Eugenics Review and replaced it with Journal of Biosocial Science and in 1969 the American Eugenics Society ended the publication of its journal Eugenics Quarterly and replaced it with Social Biology. Neither of these new journals published papers on eugenics. In addition, although eugenics societies had been founded in virtually all economically developed countries in the first half of the twentieth century, Ireland was an exception. Ireland at that time was a deeply Catholic country and the Catholics had been the only group, articulated by G. K. Chesterton, that had opposed eugenics in the first half of the twentieth century. By 1970, eugenics had become almost universally rejected. Virtually no-one supported eugenic programs anymore and anyone who proposed doing so would be accused of being a Nazi. For all these reasons, I did not think I could publish the low Irish IQ while I was in Dublin and I decided that, in order to do so, I would have to move.

In 1969, the consensus that there are no race differences in intelligence was challenged by Art Jensen in his paper How much can we boost IQ and scholastic achievement? [11] In this he argued that the 15 IQ point difference between Blacks and Whites in the United States was likely to have some genetic basis. To quote his words, “it is not an unreasonable hypothesis that genetic factors are implicated in the average Negro–White intelligence difference”. This paper generated a storm of protest. I read Jensen’s paper and concluded that he was right. I discussed it with Hans Eysenck who said he agreed and in 1971 [12], he published his book Race, Intelligence and Education, in which he summarised the evidence for this. About the same time, William Shockley began lecturing and publishing papers arguing that the Black IQ deficit is largely genetic (Shockley, 1971) [13] and this also generated a lot of publicity on account of his being a Nobel prize-winner for the invention of the transistor.

Lynn’s father was Sydney Harland, a British geneticist. He had an affair with Lynn’s mother at some point, but did not join the family. As such, Lynn was raised by a single mother in the 1930-1940s England. Lynn certainly inherited behavior from his father, in that Lynn’s career is essentially that of a collector of biological specimens — except that Lynn chose to collect human intelligence data instead of plants! And he sure did a lot of collecting. Lynn remained active in publishing almost up to his death at the age of 93, spanning over 50 years. Here’s a list of his most famous books, many of which will be familiar to the reader:

- 1997. Dysgenics: Genetic Deterioration in Modern Populations.

- 2001. The Science of Human Diversity: A History of the Pioneer Fund.

- 2001. Eugenics: A Reassessment.

- 2002. IQ and the Wealth of Nations. With Tatu Vanhanen.

- 2006. IQ and Global Inequality. With Tatu Vanhanen.

- 2006. Race Differences in Intelligence: An Evolutionary Analysis. (Second edition 2015, currently being revised.)

- 2008. The Global Bell Curve: Race, IQ, and Inequality Worldwide.

- 2011. The Chosen People: A Study of Jewish Intelligence and Achievement.

- 2012. Intelligence: A Unifying Construct for the Social Sciences. With Tatu Vanhanen.

- 2015. Evolution and Racial Differences in Sporting Ability. With Edward Dutton.

- 2019. The Intelligence of Nations. With David Becker.

- 2019. Race Differences in Psychopathic Personality: An Evolutionary Analysis. With Edward Dutton.

- 2020. Memoirs of a Dissident Psychologist.

- 2021. Sex Differences in Intelligence: The Developmental Theory.

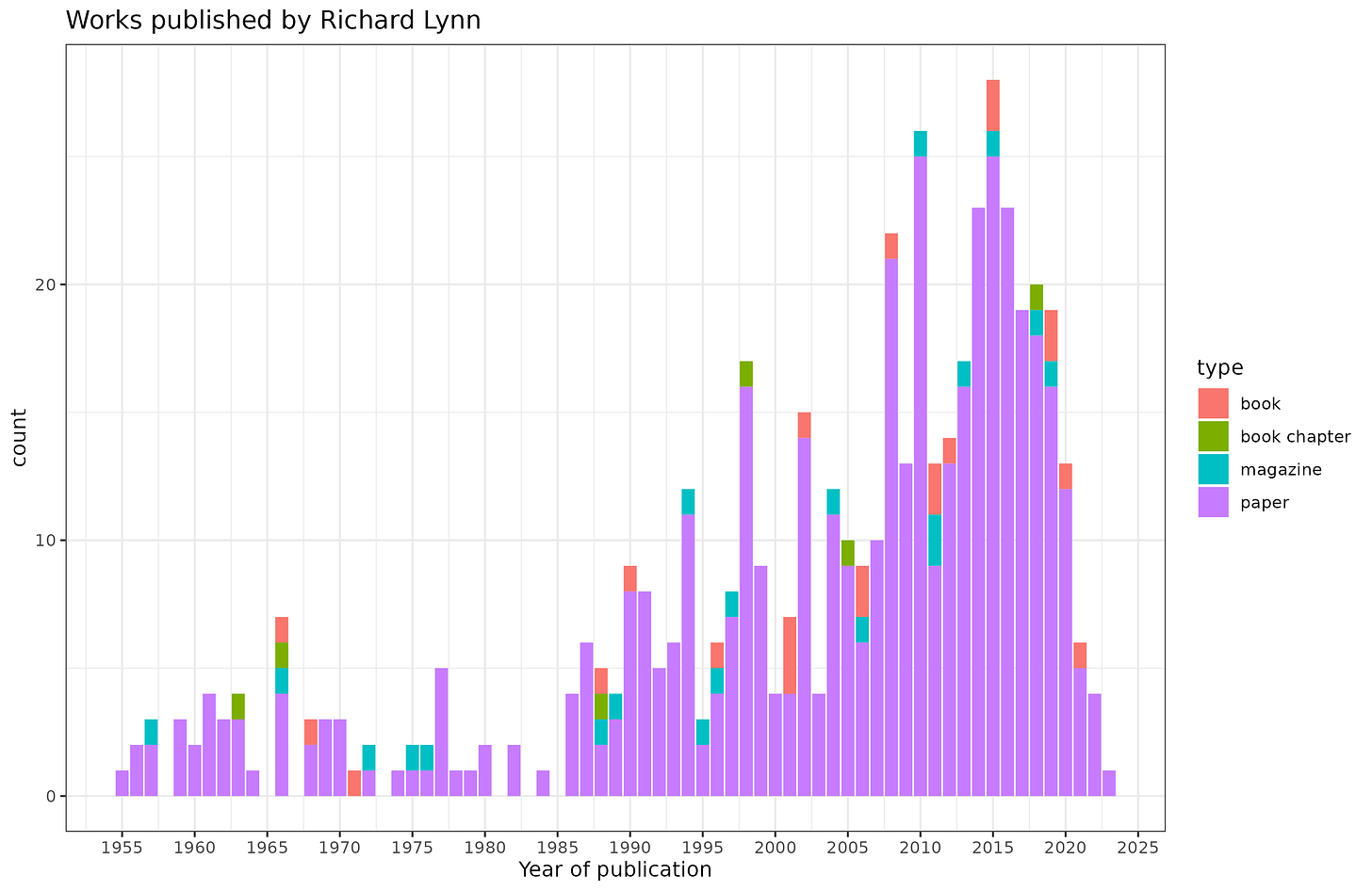

We attempted to compile a list of his compilations. We found 445 academic papers, 22 books, 20 magazine/newspaper articles, and 6 book chapters, so in total 493 works. We probably missed some, so the true count is probably slightly north of 500 publications. Here’s a timeline of his extraordinary productivity:

Unusually, Lynn accelerated his speed of publication in his older age, the opposite of the usual pattern seen for academics and creative workers in general. I can think of several reasons for this. First, it got easier to publish with better technology. Second, after he was pensioned, he no longer had to fear social sanctions for his work, as he did when he was a professor. Third, as he got more famous, it was much easier to find coauthors to work with, and one can publish more work when one has more coauthors. Still, managing to put out 20+ papers a year while being over 80 years old is almost unheard of.

The Flynn-Lynn effect

Many people mistakenly think that James Flynn discovered the Flynn effect, which is named after him. Secular increases in intelligence test scores had been noted already in the 1930s. Lynn published a review of this work in 2013 (Who discovered the Flynn effect? A review of early studies of the secular increase of intelligence):

The term “the Flynn effect” was coined by Herrnstein and Murray (1994, p.307) to designate the increases in IQs during the twentieth century that were documented for the United States and for a number of other countries by Flynn (1984, 1987). This designation has led many to believe that it was Flynn who discovered the phenomenon. Thus, the rise of IQs “has been called the Flynn effect after its discoverer” (Newcombe, 2007, p. 74); “Flynn’s discovery” (Zhu & Tulsky, 1999, p.1,255); “Flynn, a New Zealand psychologist who discovered that IQ scores are inflating over time” (Syed, 2007, p.17); and “the insight that made him famous…intelligence scores are rising, James R. Flynn has discovered” (Holloway, 1999, p.3).

These attributions are misplaced. There were numerous reports of secular increases in intelligence during the half century before they were rediscovered by Flynn in 1984. The first objective of this paper is to summarize these early and largely forgotten studies. Who knows today of the work of Runquist (1936), who first discovered the effect? Or of Roesell (1937), Johnson (1937), Wheeler (1942) or Smith (1942) who published early reports on this phenomenon? None of these names appear in textbooks on intelligence such as those of Brody (1992), Sternberg (2000), Hunt (2011), Mackintosh (2011) and Sternberg and Kaufman (2011), or even in books wholly devoted to the Flynn effect by Neisser (1998) and Flynn (2007). The second objective of this paper is to discuss the implications that can be drawn from these early studies.

James Flynn had a piece in the same issue of the journal and his commentary began thus: “Richard is correct.”. For this reason, some authors refer to the effect as the Flynn-Lynn effect, or FLynn effect, to show the double honor. True to his lack of self-promotion, Lynn himself suggested naming it after the first author who noted it, the Runquist effect. Still, it is true that Flynn’s work was pivotal in sparking renewed interest in the score gains, an interest that remains to this day. In terms of causes, Lynn thinks he basically got it right initially:

Fifth, these results tell against most of the explanations advanced for the Flynn effect, namely that it is attributable to increased test sophistication and education (Tuddenham, 1948), “improvements in education reflecting more effective teaching” (Meadows, Herrick, Feiler, & the ALSPAC Study Team, 2007, p.58), the greater complexity of more recent environments providing greater cognitive stimulation (Williams, 1998), greater cognitive stimulation from television and media (Greenfield, 1998) and from computer games (Wolf, 2005), improvements in child rearing (Elley, 1969), more confident test taking attitudes (Brand, Freshwater, & Dockrell, 1989), the “individual multiplier” and the “social multiplier” (Dickens & Flynn, 2001) and “an enhanced real-world capacity to see the world through scientific spectacles” (Flynn, 2007, p.42). All these hypotheses predict that the effect should be absent or minimal among infants and should increase progressively through childhood and adolescence as these environmental inputs have cumulatively IQ boosting impacts, and most of them predict that that the Flynn effect should be greater for verbal abilities that are taught in schools than in non-verbal abilities. The early evidence falsifies these predictions and arguably leaves the nutrition theory impacting on infants as the most plausible explanation of the secular increase of IQs, although this has also been criticized (Flynn, 2008).

It would be historically amusing if Lynn will be chiefly remembered for correctly identifying an environmental effect on intelligence scores.

Group differences, group differences everywhere

Richard Lynn is of course most famous for his work on group differences, whether these are national and subnational differences, sex differences, or race differences. To say that he worked in areas somewhat prone to political attacks would be an understatement. Essentially all his work since 2000 concerned group differences as well as eugenics/dysgenics. Lynn was the first person to seriously study national intelligence differences, and the only prior researcher of note to have studied this previously was Raymond Cattell (1905-1998) whose 1983 edited book Intelligence and National Achievement probably inspired Lynn’s work on national differences.

His works on group differences had a large impact on my own research interests. In fact, after I emailed with Lynn in 2011 and told him I was a philosophy student, he suggested:

Have you thought about changing to psychology?

Philosophy is about words, psychology is about facts & is more satisfying.

How right he was! One year later, I changed my major to linguistics (having an extreme antipathy to the continental philosophy that is the focus of the philosophy degree at Aarhus University), but of course, I never really did much work in linguistics. While taking the degree, I spent most of my time studying psychology, statistics, genetics, programming etc. The result was my first published paper in 2013 about Danish immigration and IQ. Lynn helped me find it a place to publish it too — in Mankind Quarterly of course — and the year after he invited me to come to the first London Conference on Intelligence. The rest is history.

Lynn’s work on national intelligence differences started, as he mentioned above, back with his studies of Irish intelligence and economic underperformance relative to the United Kingdom. Ironically, Ireland is now one of the wealthiest countries in the world on paper, owing to their tax haven status for large multinational companies, while the United Kingdom is falling behind in international rankings. His work on national differences in intelligence show them to be very reliable over time. Here’s a table of Lynn’s original 1978 estimates versus Becker’s 2019 estimates:

The correlation is .81, excellent considering the small number of studies available at the time. Replication is a key tenet of science, something it has taken the mainstream psychologists decades to appreciate.

Lynn’s research on the causality of national intelligence differences was very limited in methodology. Essentially, he noted the evidence that intelligence is causal for income, education etc. at the level of persons as supporting evidence, but did not try to use econometric methods to establish causality at the national level, just publishing the correlations. Later Jones & Schneider (2006) showed that intelligence is a great predictor using Bayesian model averaging, and certainly better than most other factors that have been advocated by popular authors. We replicated and extended this result in 2022:

Since Lynn and Vanhanen’s book IQ and the Wealth of Nations (2002), many publications have evidenced a relationship between national IQ and national prosperity. The strongest statistical case for this lies in Jones and Schneider’s (2006) use of Bayesian model averaging to run thousands of regressions on GDP growth (1960-1996), using different combinations of explanatory variables. This generated a weighted average over many regressions to create estimates robust to the problem of model uncertainty. We replicate and extend Jones and Schneider’s work with many new robustness tests, including new variables, different time periods, different priors and different estimates of average national intelligence. We find national IQ to be the “best predictor” of economic growth, with a higher average coefficient and average posterior inclusion probability than all other tested variables (over 67) in every test run. Our best estimates find a one point increase in IQ is associated with a 7.8% increase in GDP per capita, above Jones and Schneider’s estimate of 6.1%. We tested the causality of national IQs using three different instrumental variables: cranial capacity, ancestry-adjusted UV radiation, and 19th-century numeracy scores. We found little evidence for reverse causation, with only ancestry-adjusted UV radiation passing the Wu-Hausman test (p < .05) when the logarithm of GDP per capita in 1960 was used as the only control variable.

Sex differences in intelligence

Lynn delights in quoting authorities in a field confidently claiming something, and then proving them wrong. Here’s the opening of his 2017 summary on sex differences in intelligence:

The equal intelligence of males and females has been almost invariably asserted from the early twentieth century up to the present. Two of the first to advance this conclusion were Burt and Moore (1912) and Terman (1916). In the second half of the century it was frequently restated. Typical conclusions by leading authorities are those of Cattell (1971, p. 131): “it is now demonstrated by countless and large samples that on the two main general cognitive abilities – fluid and crystallized intelligence – men and women, boys and girls, show no significant differences”; Brody (1992, p. 323): “gender differences in general intelligence are small and virtually non-existent”; Eysenck (1981, p. 40): “men and women average pretty much the same IQ”; Herrnstein and Murray (1994, p. 275): “the consistent story has been that men and women have nearly identical IQs”; Mackintosh (1996): “there is no sex difference in general intelligence worth speaking of ”; and Hutt (1972, p. 88): “there is little evidence that men and women differ in average intelligence”. Others who stated the same conclusion include Maccoby and Jacklin (1974, p. 65) and Geary (1998, p. 310).

The assertions that males and females have the same average IQ continued to be made in the twenty-first century. Lubinski (2000): “most investigators concur on the conclusion that the sexes manifest comparable means on general intelligence ”; Colom et al. (2000): “we can conclude that there is no sex difference in general intelligence”; Loehlin (2000, p. 177): “there are no consistent and dependable male-female differences in general intelligence”; Lippa (2002): “there are no meaningful sex differences in general intelligence”; Jorm et al. (2004): “there are negligible differences in general intelligence”; Anderson (2004, p. 829): “the evidence that there is no sex difference in general ability is overwhelming”; Spelke and Grace (2007, p. 65): “men and women have equal cognitive capacity”; Hines (2007, p. 103): “there appears to be no sex difference in general intelligence; claims that men are more intelligent than women are not supported by existing data”; Haier (2007): “general intelligence does not differ between men and women”; Pinker (2008, p. 13): “the two sexes are well matched in most areas, including intelligence”; Halpern (2007, p. 123): “there is no difference in intelligence between males and females…overall, the sexes are equally smart”; Mackintosh (2011, p. 380): “the two sexes do not differ consistently in average IQ”; Halpern (2012, p. 233): “females and males score identically on IQ tests.”

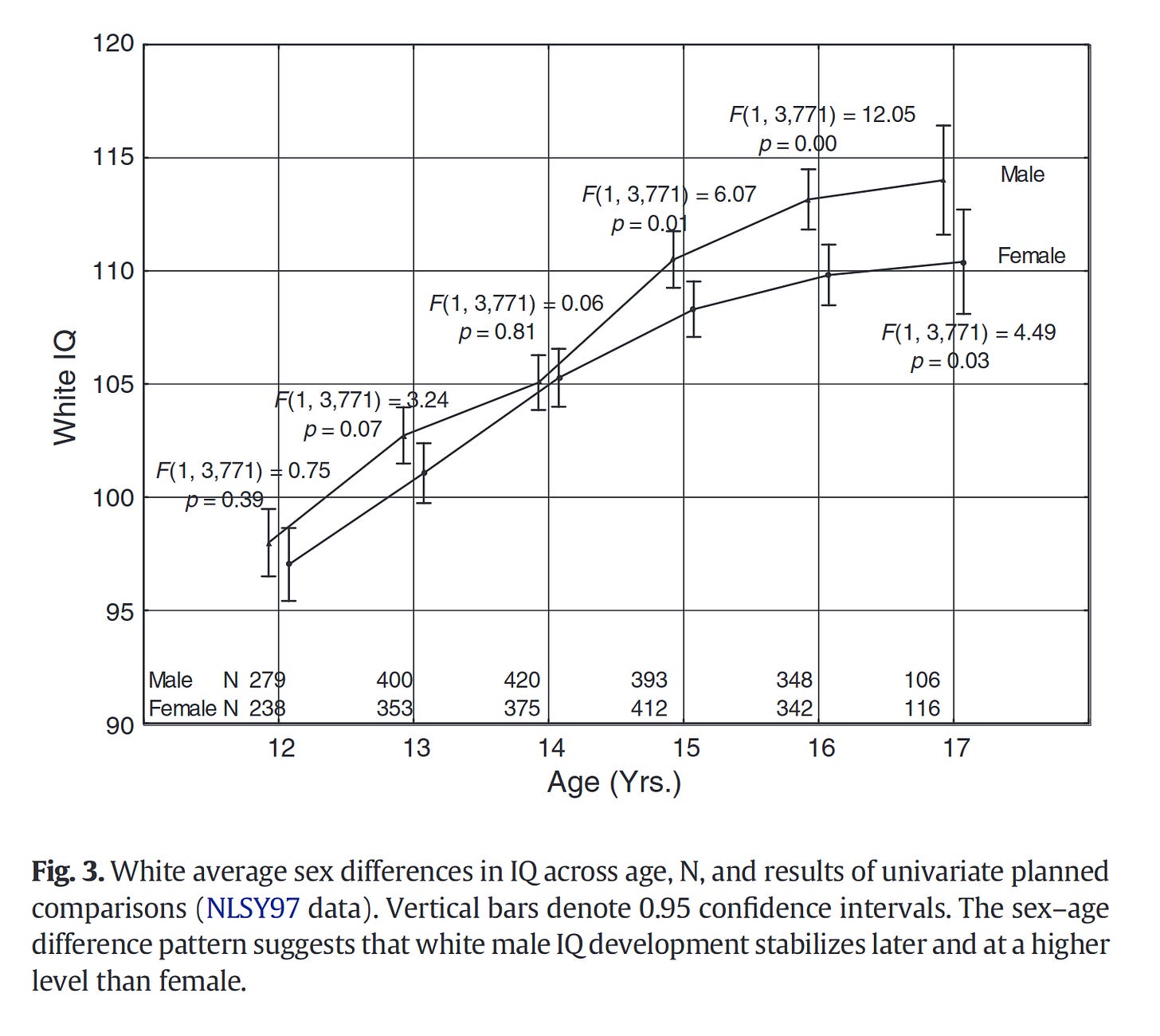

But it isn’t really so. The error these authors have been making is to neglect the effect of age. Sex differences in cognitive abilities are very small for children, it is true, but they start showing up with age. Here’s a study by Nyborg (2015):

There is a large amount of research on such post-pubescence differences, which I reviewed in 2021. That is not to say the data are perfectly consistent, but it is certainly more consistent in the direction of favoring men than showing no differences. Almost no research show a female advantage.

Dysgenic problems and eugenic solutions

Lynn’s two books on dysgenics and eugenics likewise got me to think more seriously about the problem and the potential solutions. True to his style, Lynn was ahead of the time in recommending technological solutions:

There’s no sub-chapter on surrogacy but otherwise it’s pretty much a list of currently trending technologies. The book might also contain one of the first discussions of predicted East Asian supremacy in the 2100s, as the west declines from dysgenics and political correctness. The jury is still out on that front as East Asia has even larger fertility issues than the west, and do China is moving back towards communist authoritarianism from their capitalist liberation.

Richard Lynn as a man

When I learned of his work, I read the usual online sources about him. These gave me the expectation that he has a hard nosed, perhaps mean spirited, political conservative. My actual experience with him over the years taught me exactly the opposite. Richard was a gentle, polite, scientific autist, who did not often talk about politics. In this aspect, he was similar to his long time friend Arthur Jensen. The various political extremisms attributed to him can best be described as projection by the ones writing them. Rest in peace, Richard.

Thank you very much for this information about Richard, having him for a father or grandfather would have truly been a gift.

Marvelously informative. Thank you.

RIP, from Belfast NI.

For so long we have been fed lies there is no difference between the races. The Economist did publish articles on “The Neanderthal genes” when blacks were dying in hordes in the China sniffles. This gene 🧬 seems to effect their low IQ as well. And men having higher IQ than women I think most of us suspected since long. You just need to watch a woman trying to park a car… 🅿️ 🚗

Parking a car is not a task well-assessed by current IQ tests which I believe largely deal with abstraction. Africans and Austronesians excel at activities requiring hand eye co-ordination and simultaneous movement. They tend not to excel as much when a multiplicity of inputs must be processed for immediate action, as in the quarterback role in American football or fly-half in Rugby football.

No question that male and female brains have different strengths and weaknesses. Are men smarter on average? It probably depends on the problem. The gap seems to be small, much less than between Japanese and N. Europeans.