Emil Kirkegaard’s blog: DNA, Race, and Reproduction (Emily Klancher Merchant (Editor), Meaghan O’Keefe (editor))

Book review: DNA, Race, and Reproduction (Emily Klancher Merchant (Editor), Meaghan O’Keefe (editor))

“racist garbage”

The chapters are as follows:

- Introduction: DNA, Race, and Reproduction in the Twenty-First Century

- Emily Klancher Merchant and Meaghan O’Keefe — 1

- DNA and Race

- Are People like Metals? Essences, Identity, and Certain Sciences of Human Nature — Mark Fedyk — 29

- A Colorful Explanation: Promoting Genomic Research Diversity Is Compatible with Racial Social Constructionism — Tina Rulli — 43

- Eventualizing Human Diversity Dynamics: Admixture Modeling through Time and Space — Carlos Andrés Barragán, Sivan Yair, and James Griesemer — 63

- DNA and Reproduction

- Selling Racial Purity in Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Testing and Fertility Markets — Lisa C. Ikemoto — 93

- Reproducing Intelligence: Eugenics and Behavior Genetics Past and Present — Emily Klancher Merchant — 120

- Race and Reproduction

- Evangelical Christianity, Race, and Reproduction — Meaghan O’Keefe — 153

- How Does a Baby Have a Race? — Alice B. Popejoy — 182

- Conclusion: Clinical Implications

- Meaghan O’Keefe and Cherie Ginwalla — 199

So it’s a rather short book. It has some curious parts. For instance, the co-editor O’Keefe has a chapter attacking the rather benign and kind evangelical Christians. Somewhat out of place for the book, but I guess she has a beef with them for whatever reason. As typical of edited books, most of the chapters aren’t of any interest, and usually the editors own work is what they wanted to get published somewhere, and asked some friends to send them some semi-relevant chapters for inclusion.

Some quotes from the book with my comments:

The use of race in the clinical setting suggests that “racially profiling doctors” have internalized crude race realism in making their assumptions about patients.Were crude race realism true, it would better allow the inference from individual to gene or trait because race realism is the view that races are discrete and essentialist. So being of race X means having the features that people of race X have.This kind of race realism is false. We have no justification for sliding back into it in medical practice. In addition to the dangers of misdiagnosis, this practice sends the message that crude racialist races are real.

But the statistical notion of race, endorsed by some scientists and doctors, does not license the inference either. At best, among a group of people similarly racialized, we see an increase in some clinically relevant alleles in the group. But one is guilty of committing the ecological fallacy when one moves from this group-level statistic to inference about individual risk. Higher incidence of Y among a defined population does not mean an individual member of the group has a higher risk of Y. This is starkly the case when the criterion for grouping itself is not medically or biologically meaningful.

In pretty much all these kinds of books, you will find lengthy attacks on some kind of Platonic model of race that no one has subscribed to for 200 years (that’s why they don’t provide quotes for these views). In this book, they also try to attack what they call the statistical notion of race. I guess one could in theory commit an ecological fallacy this way described, but this happens with certain odd-shaped statistical distributions. Wikipedia provides a hypothetical example where groups differ in mean IQ but the medians don’t match (because tails may be very long and different). In real life, medians and means are pretty much always in the same relative distance so this doesn’t apply. In any case, their hypothetical example is also wrong since of course, conditional on a group membership with a higher risk (and nothing else), any particular individual from that group also has a higher risk of having some bad allele(s).

Medical anthropologist Duana Fullwiley has told her personal experience of the social constructedness of race, in order to counter genetic race. “I am an African American,” says Fullwiley, “but in parts of Africa, I am white.” To do fieldwork as a medical anthropologist in Senegal, she says, “I take a plane to France, a seven- to eight-hour ride. My race changes as I cross the Atlantic. There, I say, ‘Je suis noire,’ and they say, ‘Oh, okay—métisse—you are mixed.’ Then I fly another six to seven hours to Senegal, and I am white. In the space of a day, I can change from African American, to métisse, to tubaab [Wolof for “white/European”].”82 AncestryDNA’s “ethnicity estimate” is, at best, misnamed. Despite this, the website promises that as the company database grows, you will receive updates that correct the “ethnicity estimate.”

A common mistake is their confusion between perceptions and reality. This passage provides such an example. Yes, different social contexts classified people differently because it makes sense to do so in those contexts. But this is not related to how reality works, just how humans choose to deal with fuzzy boundaries in this or that context. Ancestry testing will give the correct proportions (insofar as their models are well-trained and trying to make sensible inferences!). 23andme may tell you incorrectly you have 20% German ancestry, when all your family records show British. This is because British and German ancestry are very closely related (due to the Germanic migrations in 5th century and some later Norse migrations to England). But the models never accidentally classify an ordinary White American as 40% East African, 20% Chinese etc. The errors are not random. In some of our work, Indians were incorrectly scored as having European ancestry. Why? Well, because the model was a bit confused by shared Indo-European ancestry. No good model confuses Africans and Chinese, or Russians and Aborigines.

In my 2021 paper, I showed how perceived race (either by the subjects themselves or any 3rd parties such as parents or interviewers) is very strongly related to genetic race (that is, real ancestry). Depending on the context and the social classification scheme in use, such statistical relationships may be extremely tight or a bit more loose. Latin America usually shows looser associations, while North America usually shows very strong associations. Concerning the usual Black vs. White or both self-reported racial identity, we can get a plot like this one:

I don’t think this topic is particularly difficult to understand. People vary for various historical reasons in their proportions of this or that genetic ancestry (race). In a given social situation, people will come up with labels to describe this variation to the extent it is useful and relevant. These informal, verbal descriptions aren’t necessarily great for every person (are people from Bhutan Asians? Well, kinda sorta?), but they work reasonably well for most cases, and that’s good enough. There is no need to spend several decades trying to create confusion about this topic.

In a society where neoliberalism has prevailed, many aspects of our personal, even intimate, lives are governed through choice.114 That is, our identities are partially formed in relation to commerce, through the exercise of free-market individualism.In identity markets based on genetic ancestry testing and sperm banking, companies offer genetic race and its components, racial purity and the new polygenism, in carefully curated, color-coded bundles. Free-market ideology says that consumers have freedom to use genetic race as they see fit. Yet market practices have preselected and refined the choices in ways that affirm the validity of genetic race and racial purity.

Ah yes, the mandatory complaining about neoliberalism. Capitalism can be faulted here for telling curious customers where their ancestors are from. Perhaps the author (Lisa C. Ikemoto, an Asian American lawyer) would prefer there to be some state centralized agency telling those hapless consumers which results we are allowed to be told about.

Writing about the Collinses in Bloomberg, Carey Goldberg says that “choosing your embryo based on its odds of earning a graduate degree is still a long way off from eugenics.”7 She is wrong. Eugenics is a scientific and political program first described in 1865 by the English polymath Francis Galton. He began with a policy proposal: that a range of social problems could be solved by breeding humans like livestock, selecting for socially desirable characteristics and against socially undesirable characteristics.8 He then developed a scientific program that aimed to support selective breeding by demonstrating that mental and moral traits are primarily determined by biological material that is passed intact from generation to generation, what we now know as DNA.9 In the pursuit of such evidence, Galton and his followers developed some of the fundamental tools of inferential statistics, tests for measuring intelligence, and methods for estimating the heritability of intelligence, or the proportion of variance in intelligence attributable to genetic variation.

The word game. Usually, the discussion is about which degree we can label the political outgroup as the big R word (racist), but in this subgenre, the game is which exact technologies to label the big E word, eugenics. I am happy to accept a relatively broad definition and I think eugenicist is a good label for myself. Yes, of course I think we should improve our collective gene pool, and prevent fetuses with severe issues from being born. We have plenty of possible future people (embryos) to choose from, so we might as well choose ones that look like they have decent chances to achieve health, happiness and success in life. Which parent doesn’t want this for their child? Other parents generally agree with me, that’s why they have been aborting down syndrome fetuses for decades (as well as other severe defects detectable with simply methods). Denmark famously made international news when it was made public that 95%+ of detected Down syndrome cases were aborted and the syndrome was ‘dying out’ as the Danish journalists put it. A decade later, Iceland published statistics showing a 99% abortion rate for detected cases. No one is forcing you to do this, you could just having such a child and deal with the consequences. The welfare state will even generously support you in this decision.

I am also happy to see that the usually much maligned Galton got some credit for his amazing achievements. This is not usually done in these kinds of books.

Since heritability can range only from 0 to 1 (100 percent), a heritability of 80 percent, or 0.8, seems quite high. It is important to remember, however, what heritability means. It is an estimate of how much of the variance in a trait in a sample is due to genetic variance in the sample. It says nothing about how susceptible the trait is to change through environmental interventions. Jensen, however, claimed otherwise. He argued that a heritability of 0.8 meant that “if everyone inherited the same genotype for intelligence . . . but all non genetic environmental variance . . . remained as is, people would differ, on the average, by 8 IQ points.” However, “if hereditary variance remained as is, but . . . all non genetic sources of individual differences were removed . . . , the average intellectual difference among people would be 16 IQ points.”63 Jensen therefore argued that the higher the heritability of a trait, the less it could be altered through environmental manipulation.

Jensen must have known that this interpretation was simply untrue, as a 1958 study in rats had clearly demonstrated that genotype and environment are not independent of one another: the amount of difference genes make depends on the environment, and the amount of difference the environment makes depends on genes.64 There is therefore no way to say how much variance there would be under a fixed environment, or how much variance there would be under a fixed genotype, without specific information about the environment or the genotype. In other words, the numbers Jensen provided for these hypothetical scenarios were pure speculation. He nonetheless announced that “these results decidedly contradict the popular notion that the environment is of predominant importance as a cause of individual differences in measured intelligence in our present society.”65 Other scholars in the emergent field of behavior genetics would have know that Jensen’s conclusions were unwarranted. Publishing in PNAS, however, allowed Jensen to get away with these misleading claims. As a high-profile general science journal, its audience likely would not have known enough about the genetics of behavior to do anything other than take Jensen at his word.

There is an entire section about how bad Jensen was concerning heritability studies. As usual, this is based on selective quotation. It’s hard to see how after 50+ years, the 1969 article can still be misrepresented. I didn’t find it particularly difficult to understand. It has held up quite well, and is definitely worth a read if you haven’t read it before.

The particular quote chosen above is novel and reflects the confusion of the author (when they do doctored quotes, look for the “…” meaning they cut out something). What Jensen wrote is a rather trivial mathematical explanation of how variances work. Here’s the full quote from the 1967 paper:

This statement can be expressed, also, in terms of the average difference in IQ between persons paired at random from the population.20 Given an intelligence test like the Stanford-Binet, with a standard deviation of 16 IQ points in the white population of the United States, the average difference among such persons would be 18 IQ points. If everyone inherited the same genotype for intelligence (i.e., h2 =0), but all nongenetic environmental variance (i.e., E2 + e2) remained as is, people would differ, on the average, by 8 IQ points. On the other hand, if hereditary variance remained as is, but there were no environmental variation between families (i.e., E2 = 0), the average difference among people would be 17 IQ points. If all nongenetic sources of individual differences were removed (i.e., E2 + e2 = 0), the average intellectual difference among people would be 16 IQ points. (Errorin measurement has been subtracted from all these figures.) These results decidedly contradict the popular notion that the environment is of predominant importance as a cause of individual differences in measured intelligence in our present society. The results show, furthermore, that current IQ tests certainly do reflect innate intellectual potential (to a degree indicated by h2), and that biological inheritance is far more important than the social-psychological environment in determining differences in IQ’s. This is not to say, however, that as yet undiscovered biological, chemical, or psychological forms of intervention in the genetic or developmental processes could not diminish the relative importance of heredity as a determinant of intellectual differences.

Notice the part at the end here which is in the same paragraph that she is quoting from! Jensen says exactly the opposite thing of what she is claiming. Such dishonesty is the norm with these quote miners.

Geneticists in the 1960s knew that Jensen’s and Shockley’s claims for a genetic basis to average IQ differences between Black and white Americans had no foundation in heritability studies or any other scientific evidence.69 Heritability estimates refer only to the proportion of variance within a sample that is due to genetic variation; they can say nothing about the cause of differences between samples. As the population geneticist Richard Lewontin explained, “the fundamental error of Jensen’s argument is to confuse heritability of a character within a population with heritability of the difference between two populations.” This was a problem because, according to Lewontin, “between two populations, the concept of heritability of their difference is meaningless.”70 At the end of the 1960s, the heritability of intelligence had been estimated only in white Americans and Europeans. Such estimates provided no evidence regarding the source of average IQ differences between Black and white Americans or any relative genetic superiority or inferiority for either group vis-à-vis the other. Indeed, there was—and still is—no scientific method to assess the role of genetics in producing group-level differences in IQ or any other trait. Given the structural racism that has always plagued the United States, it is just as plausible that African Americans have the superior genetics, but that these are overwhelmed by an environment of severe oppression.71

Lewontin (a devoted communist) deserves much of the blame for these dishonest tactics. Jensen and others at the time were well aware of the relationships between within and between group heritability. As a matter of fact, Jensen himself wrote about it in the 1969 article:

T h e above discussion should serve to counter a common misunderstanding about quantitative estimates of heritability. It is sometimes forgotten that such estimates actually represent average values in the population that has been sampled and they do not necessarily apply either to differences within various subpopulations or to differences between subpopulations. In a population in which an overall H estimate is, say, .80, we may find a certain group for which H is only .70 and another group for which H is .90. A ll the major heritability studies reported in the literature are based on samples of white European and North American populations, and our knowledge of the heritability of intelligence indifferent racial and cultural groups within these populations is nil. For example,no adequate heritability studies have been based on samples of the Negro population of the United States. Since some genetic strains may be more buffered from environmental influences than others, it is not sufficient merely to equate the environments of various subgroups in the population to infer equal heritability of some characteristic in all of them. The question of whether heritability estimates can contribute anything to our understanding of the relative importance of geneticand environmental factors in accounting for average phenotypic differences between racial groups (or any other socially identifiable groups) is too complex to be considered here. I have discussed this problem in detail elsewhere and concluded that heritability estimates could be of value in testing certain specific hypotheses in this area of inquiry, provided certain conditions were met and certain other crucial items of information were also available (Jensen, 1968c).

So there is no direct inference from within to between by Jensen in the 1969 article or elsewhere. This was always a strawman. It is the same strawman for several decades at this point. Neven Sesardić points this out in his must-read 2005 book Making sense of heritability:

In my opinion, this kind of deliberate misrepresentation in attacks on hereditarianism is less frequent than sheer ignorance. But why is it that a number of people who publicly attack “Jensenism” are so poorly informed about Jensen’s real views? Given the magnitude of their distortions and the ease with which these misinterpretations spread, one is alerted to the possibility that at least some of these anti-hereditarians did not get their information about hereditarianism first hand, from primary sources, but only indirectly, from the texts of unsympathetic and sometimes quite biased critics.8 In this connection, it is interesting to note that several authors who strongly disagree with Jensen (Longino 1990; Bowler 1989; Allen 1990; Billings et al. 1992; McInerney 1996; Beckwith 1993; Kassim 2002) refer to his classic paper from 1969 by citing the volume of the Harvard Educational Review incorrectly as “33” (instead of “39”). What makes this mis-citation noteworthy is that the very same mistake is to be found in Gould’s Mismeasure of Man (in both editions). Now the fact that Gould’s idiosyncratic lapsus calami gets repeated in the later sources is either an extremely unlikely coincidence or else it reveals that these authors’ references to Jensen’s paper actually originate from their contact with Gould’s text, not Jensen’s.

Emily Merchant (I know, the memes write themselves) continues:

In support of his racist claims, Jensen merely pointed to his 0.8 heritability estimate, arguing that it showed environment to play little role at all in development of intelligence; he claimed that average differences between racially defined groups therefore must have at least some genetic component. Lewontin pointed out in numerous scientific and public forums that Jensen was simply wrong: even if the heritability of intelligence among white Americans was 1, or 100 percent (essentially meaning that the environment made no contribution to differences in intelligence between white Americans), this would still say nothing about the causes of average differences in intelligence between Black and white Americans.72

This is still the same error continued. There is in fact a somewhat complex mathematical relationship. This has been known for 50+ years. It’s Jensen’s variance argument which I have covered many times previously. It works like this:

- Suppose the heritability (genetically caused proportion of variance in some phenotype) is X% in two groups.

- 100-X is the non-genetically caused variance (’environmentability’).

- If the gap is caused by non-genetic factors alone, how large would these have to be?

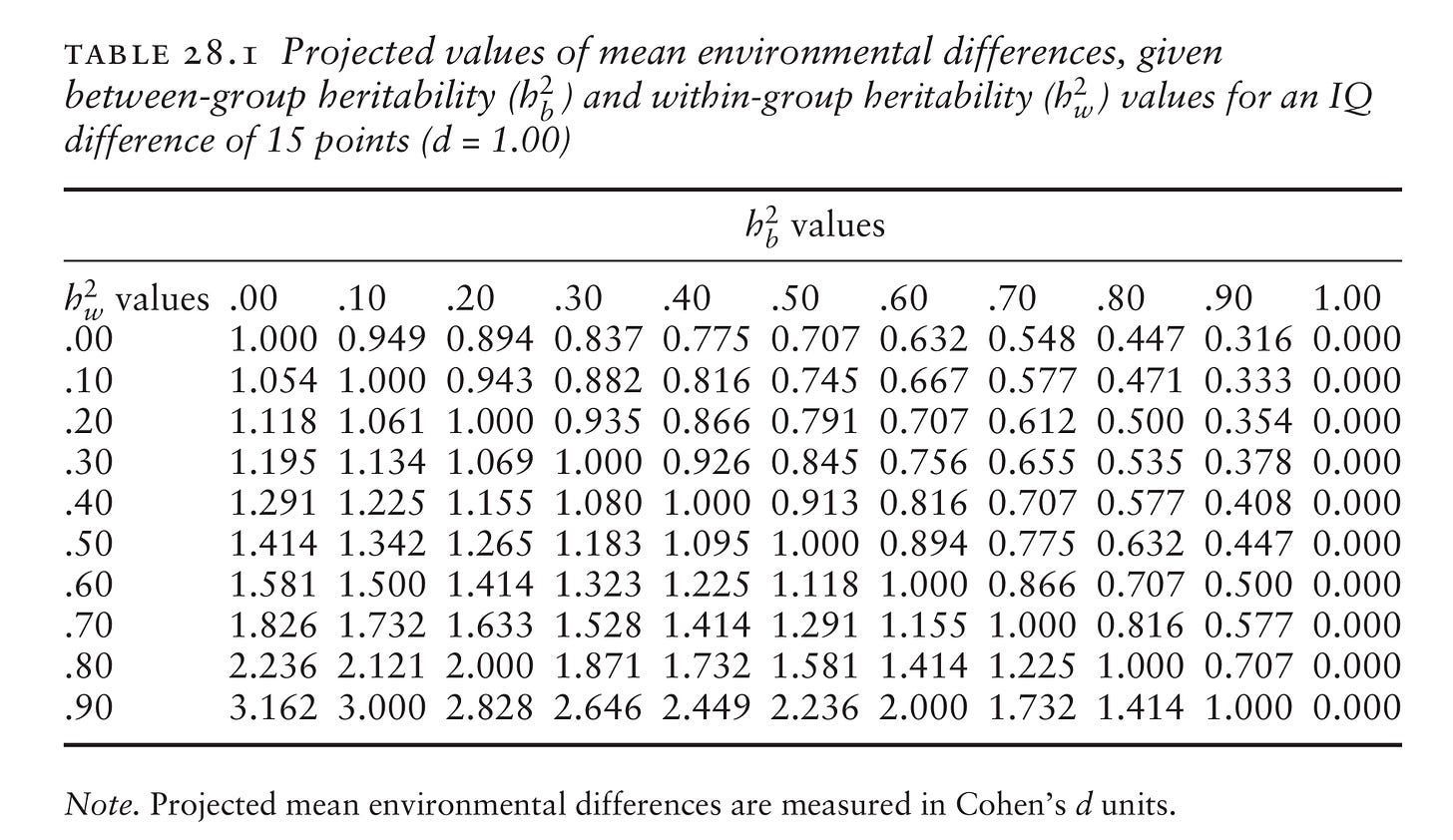

Russell Warne’s book In the Know provides us with a look-up table to answer this question:

In this case, suppose the gap on some phenotype is 1.00 standard deviation: 15 IQ, or 7 cm in height. Suppose the within group heritability is 90% (like for height), and suppose there is no difference in the height genetic causes (in the true polygenic score for height), then the non-genetic causes must be extremely strong to cause such a large difference. How strong? 3.2 standard deviations for some causes. For intelligence, heritability within group is usually estimated at around 80% for adults, and with a 1.00 d gap, the non-genetic cause would need to differ 2.2 d by the groups. The problem for egalitarians is that social groups never differ in any such cause by over 2 standard deviations. For instance, in the USA, the Black-White gap on a composite measure of social status is around 0.5, or 4+ times too small.

The most accurate part of the chapter is perhaps this claim about motivations:

While Jensen and other behavior geneticists were (and still are) happy to include this type of “genetic cause” [active gene-environment correlations, and some genetic-environment interactions that don’t exist in reality] in their heritability estimates (because it makes intelligence seem more “genetic”), it does not represent what most people think of when they imagine potential genetic effects on intelligence or education.78 Behavior genetics thus engages in a type of reasoning that is directly opposed to feminist theory, critical race theory, and disability studies, each of which separates social and somatic causes of inequality. Each of these liberatory approaches attributes inequality to discrimination, not to the bodies of the people being discriminated against. Behavior genetics does the opposite, presenting the effects of discrimination as originating in an individual’s DNA. While feminist, antiracist, and disability scholars work toward dismantling discrimination by denaturalizing inequality, behavior genetics promotes discrimination by naturalizing inequality.

Yes, this is correct! Behavioral geneticists behave as scientists and try to understand the world, that is, look for natural causes as opposed to metaphysical. Their field is not steeped in egalitarianism which seeks to ‘deconstruct’ various things using words. That is not science.

As a bonus, the book contains this footnote:

The most chilling consequence of the SSGAC’s research agenda probably could have been foreseen in advance. Just as Arthur Jensen, William Shockley, Richard Herrnstein, and Charles Murray called on heritability studies to advance the racist claims that African Americans have a lower genetic endowment of intelligence than white Americans, today’s race scientists have pointed to the results of educational GWAS to make the same racist claims.135 Although GWAS of educational attainment have been done only on white people, and although molecular behavior geneticists have warned against drawing any kind of racial comparisons on their basis, white nationalists have pointed to their results to make unsubstantiated assertions that African Americans have fewer of the intelligence- and education-producing variants than white Americans.136 The results have been nothing short of devastating. In 2022 a white supremacist cited the SSGAC’s third GWAS of educational attainment in a racist diatribe he posted shortly before perpetrating a mass shooting at a grocery store in an African American neighborhood in Buffalo, New York.137 While the SSGAC is certainly not responsible for this heinous act of violence, it underscores how easy it is to unwittingly promote racism, inequality, and even genocide when we do not understand the history of eugenics and thereby fail to recognize the eugenic projects in which we may be participating.

135. See, for example, Jordan Lasker, Bryan J. Pesta, John G. R. Fuerst, and Emil O. W. Kirkegaard, “Global Ancestry and Cognitive Ability,” Psych 1, no. 1 (2019): 431–59.

136. For an example of this kind of racist garbage, see J. Juerst, V. Shibaev, and E. O. W. Kirkegaard, “A Genetic Hypothesis for American Race/Ethnic Differences in Mean g: A Reply to Warne (2021) with Fifteen New Empirical Tests Using the ABCD Dataset,” Mankind Quarterly 63, no. 4 (June 2023): 527–600.

Evidently, miss Merchant isn’t happy with our work! I take that as a good sign.

“So, Emil, why really read this kind of work?” Well, for curiosity! Maybe somewhere in their endless anti-eugenics books (there must be at least 10 of them this decade), maybe there would be some light that goes off, some understanding. I mean, supposedly, some of these people are at least reading the right texts, but somehow keep not understanding anything, even engaging in 50+ year long strawman arguments. Nevertheless, I am an optimistic fellow. Even if no lessons were learned, at least, this should be documented too.

Over a hundred years ago eugenics was advocated as a new “religion” by thoughtful writers from Irving Fisher to Bernard Shaw as a means to prevent the death of our civilization. It has been subjected to sustained defamation, especially from the 1960s onwards. As its scientific aspects have become more complex, the means for humanitarian implementation have become more practical. It needs a vindication and revival.

One notable feature of the huge literature against “scientific racism” and eugenics is its repetition of misrepresentations; for example, the innuendo against Benjamin Kidd on the “strength” of one book, “Social Evolution”. Another thought-crime is the suppression of relevant material, from the silent excision of a paragraph against miscegenation in Santayana’s “Life of Reason” to the publisher’s “recall” of Baker’s “Race”. Little honest and balanced primary research has been done, except in a few monographs. Someone should try to refute this stuff in a single volume, now there are publishers available.

Do readers agree with Emil Kirkegaard that Nathan Cofnas is our “best living conservative philosopher”?