Freud as Charlatan and Politician

‘I’ve never done a mean thing.’ —Freud

I’ve spent my whole life battling guilt and all those words that psychoanalysis has drilled into our heads. —David Cooper [1]

Readers may have noticed that I have sometimes used the terms psychiatrist and psychoanalyst interchangeably. Before reading Jeffrey Masson, I believed they were essentially different things. It’s true that I had experience with Giuseppe Amara, who appears in the Mexican media as a psychoanalyst but acts as a psychiatrist when faced with family problems. But even so, I believed they were fundamentally different.

I was wrong. Now I know that from its origins, psychoanalysis has been linked to psychiatry, and that in North America many analysts, like Amara, were both physicians and psychiatrists. Sigmund Freud himself, who began his career as an electrotherapist, flourished thanks to an amalgamation of his system with psychiatric approaches.

Eugen Bleuler, the psychiatrist who coined the term schizophrenia, published the first psychoanalytic journal with Freud. Psychiatrists were among Freud’s earliest followers. Ludwig Binswanger and Jung, from Bleuler’s group and representatives of mainstream psychiatry in Europe, began associating with Freud in 1907. Karl Abraham, a psychiatrist from Zurich, founded the most structured psychoanalytic society in Berlin. At the first psychoanalytic congress, Abraham and Jung presented papers on dementia praecox, now known as schizophrenia, which Freud listened to favourably. Max Eitingon, also a young psychiatrist, was Freud’s first translator into English. Across the Atlantic, the American psychiatrist Stanley Hall invited Freud to the United States, where Clark University awarded him an honorary doctorate in 1909. This marked the beginning of the dissemination of Freud’s ideas in North America.

Freudian ideas are part of our cultural matrix: repressed memories, sexual sublimation, phallic symbols, castration anxiety, etc. I cannot delve into an examination of psychoanalytic theory. I will focus on those aspects of Freud’s biography in which his personality is compromised with the ideological system he created.

* * *

Freud wrote: ‘I consider ethics to be a given. In truth, I’ve never done a mean thing.’[2] To verify such extraordinary claim, it is more illuminating to read his correspondence with close friends than the official version of his life found in the hagiographies of his disciples. In his correspondence with Eduard Silberstein, his childhood friend, the young Freud wrote: ‘…whom nature has also inclined to be vain, a combination often found in girls.’[3] As can be seen in the insightful essays of F. Roger Devlin, or the internet texts by incels, this proved to be true. Where I believe Freud terribly erred was in believing that women literally envied men’s penises.

Freud’s career as a therapist began horribly. When Pauline, Silberstein’s wife, became depressed in 1891, Silberstein sent her to Freud. For unknown reasons, Pauline jumped from the fourth floor, where Freud had his office. Although some try to defend Freud by arguing that Pauline jumped without having met him yet, it should be noted that Freud never spoke about the case.[4] But I have my conjectures. Did Freud re-traumatize Pauline because of her marital problems with his old buddy? Did the young woman suffer a suicidal panic during the consultation due to re-traumatization? (I remember what Amara did to me when I was a teenager and how I left his office in a panic walking through Parque Hundido.)

It is well known that, as far as family politics were concerned, Freud sided with husbands in conflict with their wives. Similarly, like Kraepelin and Bleuler, Freud found it difficult to side with the children and easy to side with the parents. For example, the psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing was displeased by a letter he received from a nineteen-year-old girl, Nina R., stating that she had erotic dreams. He wrote to Freud accusing her of suffering from ‘psychic masturbation.’ In 1891, the year Pauline threw herself from Freud’s apartment, Freud wrote: ‘Nina R. has always been overexcited, full of romantic ideas, thinks her parents do not like her. Has the occasional fantasy that her father does not love her. The patient does nothing but read and write’ (this somewhat echoes Amara’s diagnosis). Two years later, Freud wrote to Dr Binswanger about this same young woman: ‘The inborn crookedness of her character manifested itself in her forgetting her immediate duties, her adjustment to her milieu, while she strove to gain interests on a more idealistic level and absorb more exalted intellectual stimuli.’[5] Freud went so far as to send some women to the Bellevue psychiatric hospital in the 1890s.[6]

In his first book, Studies on Hysteria, which he published with Josef Breuer, Freud wrote about other women. Breuer, who had obtained these patients for Freud, had been a paternal figure. In the 1880s, when Freud was still an unknown and relatively poor doctor, Breuer paid him monthly sums of money. Although he didn’t always agree with Freud’s interpretations of women in the book they published together, he expressed his differences very cautiously and respectfully toward his protégé. That was enough for the disciple to repudiate his teacher and never speak to him again for the rest of his life. Josef Breuer was deeply hurt by Freud’s disproportionate reaction. Hanna, Breuer’s daughter-in-law, recounts something that happened many years later: ‘How profoundly this break must have affected my father-in-law can be guessed from a small but significant incident that occurred when he was already an old man. He was walking down the street in Vienna when he suddenly saw Freud coming toward him. Intuitively, he opened his arms. Freud walked past him pretending not to have seen him.’[7]

This is how Freud repaid the most protective person in his life. Later, Adler, Stekel, Jung, Rank and Ferenczi, like Breuer, fell out of Freud’s favour for the same reason: they didn’t adhere to each and every Freudian doctrine. If Freud behaved this way with his protector and disciples, how must he have behaved with his defenceless patients? Besides the suicide of Pauline Silberstein, it is known for certain that Freud endangered the life of another of his patients: Emma Eckstein.

In 1895, when Freud saw that Emma wasn’t recovering from her hysteria, he summoned Wilhelm Fliess. Psychoanalysts often omit mentioning, when speaking of their mentor, that Fliess, Freud’s best friend, was ‘one of the giants of German crackpottery.’[8] Fliess was convinced that neuroses were related to the nose, so he would remove a piece of a nasal bone from his ‘severe’ patients. During the ten years of Fliess’s friendship with Freud, the latter accepted his friend’s crackpottery as genuine science. In fact, Freud even called his friend ‘the new Kepler’ for his discoveries in the field of otolaryngology. So Fliess, the new Kepler, operated on Emma.

After the operation Fliess returned to Berlin, but the young woman began to bleed uncontrollably. Alarmed, Freud took her to a real surgeon who reopened her nose and found a piece of iodized gauze that Fliess had left behind during the operation. The gauze had prevented the wound from healing properly. Although she healed after the surgeon treated her, Emma was left with a permanent disfigurement, a cavity in her cheek. However—and this is the important point—Freud interpreted what happened to Emma Eckstein in such a way that he exonerated the irresponsible quack. In one of his letters, Freud wrote to Fliess:

You were right that her episodes of bleeding were hysterical, were occasioned by longing, and probably occurred at the sexually relevant times (the woman, out of resistance, has not yet supplied me with the dates).[9]

Freud concluded: ‘As far as the blood is concerned, you are completely without blame!’[10] That business about dates was part of Fliess’s quackery, who, like an astrologer, made associations between dates and menstrual periods to predict women’s destinies. But what interests us is Freud’s interpretation. I can’t think of a better example to show how, despite the more than obvious evidence of Fliess’s guilt, in a conflict between people, the psychoanalyst exonerates his buddy, and the way to do so is by blaming the victim. I call this revictimization.

The analytical interpretation Freud applied to Emma, ‘hysterical haemorrhage,’ wasn’t a slip of the tongue in his correspondence with Fliess. In his most important work, The Interpretation of Dreams, he dedicates sixteen pages to the Emma case, using the pseudonym ‘Irma’: the longest analytical topic in The Interpretation. Freud confesses there that he had a dream about Irma (that is, Emma Eckstein). It is not relevant to transcribe it here. What is important is that, according to Freud, the dream was his own unconscious’s declaration of innocence regarding the accusation of medical error and, as Freud’s self-analysis continues, the dream blamed several people: Emma/Irma for not accepting his interpretation, Breuer, and another doctor who appeared in his dream. It is an exquisite irony that a work many consider seminal for unearthing the truth of the human mind—incidentally, The Interpretation of Dreams is Amara’s favourite book—begins by misrepresenting what Freud and Fliess did to Emma. To add insult to injury, in the year of the operation that disfigured Emma, Freud wrote a letter to Fliess asking if the house where he had the dream about Emma would one day bear a marble plaque with a lapidary inscription, in Freud’s own words:

Here, on July 24, 1895,

the secret of the dream was revealed

to Dr Sigmund Freud. [11]

Ten years later, in 1905, Freud wrote to Emma and brought up the subject of Fliess’s botched operation again. One might assume that after so many years, the great connoisseur of the human soul would have examined his conscience and regretted what he and his buddy had done to her. This was not the case. In the letter, Freud continued to accuse her of believing that her problem was physical and that another doctor had cured her. Incredibly, Freud reiterated that Emma’s ‘resistance’ to his interpretation was responsible for his ‘psychoanalysis’ not having been successful. [12]

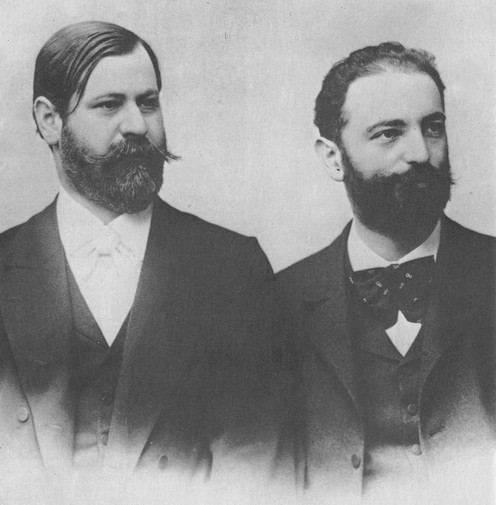

Sigmund Freud and Wilhelm Fliess in 1890.

Sigmund Freud and Wilhelm Fliess in 1890.

The most serious blunder in Freud’s career, one that would wreak havoc not on a couple of women but on how his followers treated their clients throughout the 20th century, was his repudiation of one of his discoveries.

At the end of the 19th century, Freud had noticed that some women who consulted him suffered from memories of having been raped by their fathers: something that went down in history as ‘the seduction theory.’ In 1896 Freud wrote an article on the subject, ‘The Aetiology of Hysteria.’ Jeffrey Masson suggests that, seeing that these revelations only alienated him from his colleagues in a Vienna incapable of putting the respected fathers on the dock, Freud, much like the psychiatrists, reversed his ideology and decided to blame the victims. Freud labelled them ‘hysterical’ and defined hysteria as a hidden desire to be seduced. It is now known that incest has occurred more frequently than was accepted in 19th-century Europe, but this reversal of blame was to be the cornerstone upon which Freud would build his edifice. For psychoanalysis, the year 1897 marks both the abandonment of Freud’s seduction theory (if you say your father molested you…) and the ‘discovery’ of the Oedipus complex (…it means you were actually fantasizing about it).

In 1900 Freud saw Ida Bauer for the first time, whom he called ‘Dora’. Mr. K., an industrialist and friend of Dora’s dad, tried to seduce her twice: the first time when she was just thirteen-year-old and the second time when she was fifteen. Mr. K. forcibly kissed her on the mouth and Dora responded ‘with a vivid sense of disgust.’[13] When the girl reported the situation her father wanted to take her to a doctor. Dora refused: all she wanted was to be vindicated against Lolita’s harasser. But eventually, she relented.

In a session with Freud, the seventeen years old Dora told him her story. Since her father hadn’t supported her, perhaps Dr Freud would. Freud listened to her for several sessions and, unlike her father, believed her story. But he did something more. The following is a quote from an article in which Freud confesses what he told Dora in their consultation:

You will agree that nothing makes you so angry as having it thought that you merely fancied the scene by the lake [the place of the seduction]. I know now—and this is what you do not want to be reminded of—that you did fancy that Mr K.’s proposals were serious, and that he would not leave off until you had married him.[14]

This is one of the sins that analysts commit daily. Right now, one of them is ‘interpreting’ the mind of one of their unsuspecting clients in a manner as capricious as this. Another example is how Amara interpreted my running away to my grandmother’s house as a result of feeling insecure before my siblings. When Freud interpreted her as being in love with a man three times her age, and as having felt disgusted when Mr. K. tried to kiss her being ‘hysterical’—Freud assumed that if Dora were normal, she would have responded with pleasure—, the girl didn’t challenge him. She said goodbye to the Vienna quack and never set foot in his office again.

Freud took his revenge by devising the theory that if someone disagreed with the analyst’s interpretation, it was simply due to a lack of insight, a refusal to confront her own psychological reality. This overinterpretation, elevated to a doctrine in psychoanalysis, he christened ‘resistance’: a concept he had already used in the case of Emma Eckstein. For Freud and psychoanalysts, this word means that, once the analyst has made an interpretation, the case is closed: everything else is ‘resistance.’ Let us listen once more to Freud:

We must not be led astray by initial denials. If we keep firmly to what we have inferred, we shall in the end conquer every resistance by emphasizing the unshakable nature of our convictions.[15]

Then Freud adds that ‘this conviction has become so absolute in me…’

This is the language of the dogmatist, not of the student of the mind, much less of the mind of another person. What Freud really wanted was for Dora to fall into a state of folie à deux with him (as I fell into it with Amara when he prevented me from stopping my appointments). Freud not only failed to apologize to Dora for the stupid thing he had said about Mr. K., but he elevated his foolish interpretation to the level of science, employing all the literary resources of his intellect. Freud’s essay on Dora, Fragment of an Analysis of a Case of Hysteria, is the most extensive clinical history in Freud’s legacy and the most cited work on female ‘hysteria.’ In Fragment of an Analysis Freud dared to interpret Dora’s cough as an expression of her desire to perform fellatio on Mr. K., and he also interpreted two of her dreams along those same sexual lines. Obviously, the teenager’s disagreement with such interpretations constituted ‘resistance.’ Not content with that, Freud also used the Dora case to develop the famous doctrine of ‘transference.’ Let us read Freud once more:

…those indications that make a transference onto me plausible. … I conclude that in one of the treatment sessions, the patient [Dora] decided she wanted me to kiss her. [16]

Freud deluded himself into believing that a young woman in her prime wanted to be kissed not only by Mr. K. but by him as well. In one of the few good biographies written about Freud, the analyst Louis Breger states that it was clear that the therapy Freud applied to Dora was quite harmful, and that it was painful to read the case today.[17] The harmful therapy appears in the excellent Mexican play Feliz Nuevo Siglo Doktor Freud (Happy New Century, Dr. Freud ) by Sabina Berman. Berman’s comedy, which I thoroughly enjoyed and which was even performed in Spain, deals precisely with what has been said here about Freud and Dora.

I wonder how someone like Freud ended up in history as an astute observer of the mind. Because analysts continue to follow Freudian doctrines, they have tarnished Dora’s image for a century without ever having met her. Masson tells us that famous analysts like Ernest Jones, Félix Deutch, Jacques Lacan and even feminists like Toril Moi have spoken of Dora with contempt. Jenny Pavisic, a Lacanian analyst, told me personally: ‘Dora was a hysteric who—.’ In other words, the folie à deux of the true believers of Freud’s ideas continues. In reality, Dr Freud blamed Dora to absolve the industrialist and blamed Emma to absolve his buddy: antecedents of what, three-quarters of a century later, Amara would do to me: blame me to absolve my parents. Throughout the 20th and early 21st centuries Freud’s followers have blamed countless Doras, Emmas, and Césares.

At the end of the 19th century, in a letter to Wilhelm Fliess, Freud confessed that, due to his essay on seduction, in which he discussed incest among the middle and upper classes, ‘the word has been given out to abandon me and I am isolated.’[18] Masson believes that Dora’s case vindicated him. His new theory of hysteria represented a complete reversal of his previous position. Now Freud no longer targeted powerful industrialists like Mr. K., but a defenceless young woman. Freud’s behaviour was in line with psychiatry: siding with parents and the wealthy classes against their victims. From this perspective, it is no exaggeration to say that psychoanalysis was founded on the betrayal of women and adolescents in early 20th-century Vienna.

The Dora case and the abandonment of his seduction theory are not venial sins of the founder of psychoanalysis. They invalidate two pillars of the Freudian edifice: the notion of hysteria and the famous Oedipus complex. But Freud also used his prestige to side with parents in conflicts with adolescent boys. This is evident in his own writings. In The Psychopathology of Everyday Life Freud recounts that a mother asked him to examine her son. Freud noticed a stain on his trousers, and the adolescent told him he had dropped an egg. Freud didn’t believe the story and spoke with the mother privately: ‘I… took as the basis of our discussion his confession that he was suffering from the troubles arising from masturbation.’[19] The point of the anecdote, and I owe this to Thomas Szasz, is that the boy wasn’t suffering from anything at all: it was an ignorant mother who was worried about her son’s emerging sexuality. Freud saw something as normal as adolescent ejaculation as ‘psychopathological.’ Whether it was due to masturbation or not, much like Catholics taking their children to confession, the boy’s emission warranted a whole medical ceremony culminating in a formal diagnosis.

This was not another hypothetical isolated slip of Freud’s. Throughout his life he shared the Victorian hysteria surrounding masturbation: real hysteria, not the ‘hysteria’ of Emma and Dora that harmed no one. Freud believed that masturbation was a very serious matter. He wrote to Fliess that masturbation was the ‘primary addiction’ from which all others arose, including addiction to morphine and homosexuality.[20] We are so accustomed to seeing Freud as the pioneer in the courageous revelation of human sexuality that it is difficult for us to see him for what he was: an exponent of the morality of his time. In fact, he didn’t tell his own children how babies came into the world but sent them to the family doctor to have it explained. The most fascinating anecdote I know on this subject is something told by Oliver Freud, one of Freud’s sons.

When Oliver was sixteen, he asked his father for advice about masturbation. The boy hoped the renowned physician of the human soul would free him from guilt. Freud did the opposite: he warned him against masturbating. In Oliver’s own words, he was ‘quite upset for some time.’[21] Louis Breger comments that Oliver had the feeling that his father’s censure had erected a barrier that prevented communication between them.[22] Years later, Oliver would be the Freud child who distanced himself most from the family. What better example to portray the real Freud, the creator of an all-encompassing theory that revolved around human eroticism? The man who founded the profession of listening to those who needed to talk about their sexuality didn’t listen to his own son!

* * *

Now I will address Freud’s stance on the political realities of his time.

The First World War was the greatest catastrophe Europe experienced at the beginning of the century. It violently awakened people from the optimistic dream of unstoppable 19th-century progress. Never before had millions died in a single war. The war not only killed and disabled many soldiers during combat, but the emotional aftermath was also felt by their wives and families.

Freud was at the height of his intellectual powers when the conflict erupted. Initially, he embraced the nationalism of the time and even told a disciple, ‘All my libido is for Austria-Hungary.’[23] Freud’s euphoria cooled, as did that of his compatriots, when the stark realities of the war and the death toll began to emerge. I cannot elaborate on the details, but I will mention Freud’s stance toward the thousands of traumatized soldiers who survived the fighting. Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory was the first movie to portray the hell of trench warfare in the First World War, including the psychological trauma of some soldiers, which in Freud’s time was termed ‘war neurosis.’ For some English and French doctors—and this is not a movie but true history—it was obvious that these traumas were caused by their experiences in the war. Currently, the term PTSD is used in some cases of veterans of the Vietnam War and the Gulf Wars.

Freud, on the other hand, was blind to the obvious. In his contribution to the monograph Psychoanalysis and the War Neurosis he wrote that the soldiers’ mental disorders had a purely sexual origin, and his close disciples seconded him. Josef Breuer, despite his advanced age during the war, helped to medically treat some of the survivors. His philanthropic attitude contrasts sharply with that of Freud, who never treated a single soldier. Freud was content to draw his conclusions directly from his theories. For Freud, these theories were laws of nature, and from them it was possible to deduce everything related to human behaviour. If Freudian theory was based on the axiom of human sexuality, then all neuroses, including ‘war neurosis,’ must necessarily have a sexual aetiology. A single case will suffice to illustrate Freud’s position. In 1919, Lou Andreas-Salomé, one of Freud’s most famous disciples, wrote to Freud about the case of a soldier whose twin brother had died in the war. Neither Andreas-Salomé nor Freud paid any attention to the loss. Under Freud’s guidance, Andreas-Salomé conducted the ‘analysis’ of the surviving twin around classic Freudian doctrines such as latent homosexuality, the Oedipus complex, and fixation on the paternal figure. [24]

The Freudian interpretation is as capricious as the interpretations of Emma and Dora or Amara’s interpretation of my running away to my grandmother’s house. But Freud was guilty of more than just a theoretical stance. The founder of psychoanalysis not only sided with powerful individuals in conflict with young women, but also with the State in conflict with soldiers.

The German psychiatrist Julius Wagner-Jauregg administered painful electric shocks during World War I to young men who wanted to leave the military. After the war, some of those treated in the psychiatric division of Vienna General Hospital, run by Wagner-Jauregg, complained, and in 1920 a commission was appointed to investigate the charges. The commission asked Freud for his opinion. Freud defended Wagner-Jauregg. And not only that: He insisted on calling the soldiers who accused the renowned doctor ‘patients’ and on referring to their fear as an ‘illness.’ The commission ruled in favour of Wagner-Jauregg. Because Freud was a man convinced of his own righteousness and believed he had never done anything mean, he never regretted what he had done to the young soldiers.[25]

I emphasize that these weren’t isolated sins in the biographies of Freud and Jung. In the entire vast body of work of these psychologists, there is not a single critical line regarding involuntary psychiatric hospitalization. Since Jung learned his trade at the Burghölzli Hospital in Zurich under Bleuler’s supervision, he was familiar with the neologism his boss coined: schizophrenia. On one occasion, Freud played the accomplice in Bleuler and Jung’s prison-like psychiatry. On May 16, 1908, Freud wrote to Jung:

Enclosed the certificate for Otto Gross. Once you have him, don’t let him out before October, when I shall be able to take charge of him.[26]

This smells like the mafia. Gross himself was a doctor who, ironically, that same year published a letter to an editor objecting to a girl’s involuntary commitment by her father. On June 17, Gross escaped from the Burghölzli. Jung retaliated by labelling him ‘schizophrenic.’ Freud enthusiastically accepted the diagnosis.[27]

In 1975, the Mexican Social Security Institute convened an international conference on psychiatry and psychoanalysis in Mexico City, in which Tom Szasz participated along with other European and Latin American psychiatrists and analysts. At a roundtable discussion, Szasz confronted his colleagues. He told them what he thought about lobotomist doctors and psychiatrists:

The other conclusion is that they are gangsters, butchers, criminals, and delinquents. That is my conclusion. And I would add that people like Freud are also sympathetic to these butchers, since for forty years he never pointed out that this was wrong. And this was happening right next door. He behaved like one of those Germans who, when the Jews were in the gas chambers, claimed not to smell anything. And finally, my conclusion is that Freud and Jung, especially Freud—who had many good ideas and was very intelligent—was basically a gangster, because he wasn’t interested in studying anything scientifically. He was only interested in building what he called the psychoanalytic movement.

Words are very important. Galileo didn’t have a movement. Darwin didn’t have a movement. Mendel didn’t have a movement. Einstein didn’t have a movement. Freud claimed to be a scientist, but since he needed a movement, this makes him a politician. The only question left is: do you like Freud as a politician or not? I find him detestable.[28]

The analysts who shared the roundtable with Szasz didn’t respond to these criticisms: that throughout his career Freud remained silent about the psychiatric crimes in the house next door. Igor Caruso and Marie Langer offended him, and Szasz had to leave the discussion.[29] But the important thing to emphasize is that these learned figures in psychoanalysis didn’t respond at all regarding Freud’s indifference to the crime. They had nothing to say.

Not only did Freud lack compassion for the victims of world war and psychiatric confinement but, like his mentor Charcot, when referring to the women persecuted by the Inquisition, he spoke of them as ‘hysterics.’ This is one of the facts that most horrified me when reading Szasz’s classic, The Manufacture of Madness: Freud and his mentor didn’t speak of perpetrators but rather diagnosed the victims of the inquisitors. In his obituary for Charcot, Freud wrote:

By pronouncing possession by a demon to be the cause of hysterical phenomena, the Middle Ages in fact chose this solution; it would only have been a matter of exchanging the religious terminology of that dark and superstitious age for the scientific language of today.[30]

As Szasz pointed out, this is an extraordinary statement. Freud acknowledges that the psychoanalytic description of hysteria is merely a semantic revision of the demonological one! Freud wrote his note in 1893. In more recent times, there are psychiatrists and historians sympathetic to psychiatry who continue to spout the exact same nonsense. For example, in Nouvelle histoire de la psychiatrie, published in France in 1983, the editors Jacques Poster and Claude Quétel wrote a biographical note on Johann Christian Heinroth and the words he used. This 19th-century psychiatrist identified mental illness with sin. Poster and Quétel commented that Heinroth’s Lutheran vocabulary had been much criticized and had fallen into disuse in our time. But they immediately added: ‘However, if we substitute the notion of “sin” with that of “guilt,” many of his ideas acquire a curiously modern dimension.’[31] Another contributor, the Mexican psychiatrist Héctor Pérez Rincón, wrote: ‘One cannot speak of the history of psychiatry in New Spain without taking into consideration … the activity of the Inquisition in some behaviours that today would be classified as psychiatric.’[32] So, in a book published a century after Freud’s pronouncement, there are psychiatrists who continue to maintain that his Newspeak is merely a semantic revision of the Inquisition’s ideology.

In the 4th century, the stigmatizing labels were pagan and heretic. A thousand years later, there were no longer any Greco-Roman pagans—they had been exterminated by the Church—only heretics, but a new group emerged to be stigmatized: witches. In 1486, the Dominican theologians Jacob Sprenger and Heinrich Krämer published the Malleus Maleficarum, literally the hammer of witches: the medieval manual that would become the ideological source of terror for countless women: an inhumane hunt that would last for centuries. The exact number of women murdered is unknown, but some estimates range from one hundred thousand to half a million. The last execution for ‘witchcraft’ took place in Poland in 1793. Incredibly, these victims of deranged Christians are not considered as such in the writings of psychiatrists. Following Charcot and Freud, psychiatrists speak of neuro-pathologies referring not to the inquisitors, but to their victims. Szasz observes that, for the historians of psychiatry Franz Alexander and Sheldon Selesnick, the fact that these women were tortured and burned was enough to make them, not their murderers, objects of medical interest. And what do psychiatrists say about the authors of the Malleus Maleficarum? Gregory Zilboorg, another historian of psychiatry, called them ‘two honest Dominicans.’ Similar words of admiration can be found in the writings of Jules Masserman, another psychiatrist.[33] Evidently these doctors, as arrogant as those medieval theologians, diagnose ‘psychopathologies’ centuries later, without having medically examined any of the women. I call this Wonderland Logic, alluding to Lewis Carroll’s story: the surrealism of punishing the victim and not the perpetrator.

The most relevant point in psychiatric Wonderland is that many psychiatrists today believe these official psychiatric narratives. Even students in the new century accept such narratives. For example, in his thesis for his undergraduate degree in psychology from the National Autonomous University of Mexico in 2001, Guillermo Gaytan wrote: ‘Sprenger and Kramer’s Malleus Maleficarum, a book that can be considered a true treatise on psychopathology, also contained a good number of corrective measures.’ [34]

Corrective measures! Does the author approve of burning women at the stake? Fortunately, for historians who are not psychiatrists or psychologists, such as Hugh Trevor-Roper, the witch hunts were clearly a paranoid enterprise of the Church. After the Enlightenment there is no excuse for viewing this chapter of history any other way. It doesn’t surprise me that an individual who labels the victim of fanatics as hysterical—Freud—treated some of his patients the way he did.

[1] David Cooper, quoted in Francisco Gomezjara (ed.): “La otra psicología” in Alternativas a la psiquiatría y a la psicología social (México: Fontamara, 1989), p. 76. This dossier of articles published in various Mexican journals and newspapers was originally published in 1982. The edition I am referring to is the expanded 1989 edition.

[2] Freud to James Putnam, quoted by Ernest Jones. On page 153 of The Myth of Mental Illness (Harper & Row, 1974), Thomas Szasz quotes it in German (“Ich betrachte das Moralische als etwas Selbstverständliches… Ich habe eigentlich nie etwas Gemeines getan.‘‘).

[3] Quoted in Louis Breger: Freud: el genio y sus sombras (Javier Vergara, 2001), p. 71. The original title is Freud: Darkness in the Midst of Vision (John Wiley & Sons, 2000).

[4] Ibid., (Spanish edition) p. 72.

[5] Cited in Masson: Against Therapy, p. 82.

[6] Ibidem.

[7] Hanna Breuer, cited in Breger: Freud, p. 174 (Spanish edition). The relationship between Josef Breuer and Freud is explained in three chapters of Breger’s book.

[8] Martin Gardner: ‘Freud and Fliess: The Sad Sage of Emma Eckstein’s Nose’ in Skeptical Inquirer (Summer 1984), p. 302.

[9] Ibid, p. 304.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Freud to Wilhelm Fliess, cited in Breger: Freud (Spanish edition) p. 196.

[12] I read this in ibidem, p. 511.

[13] Ibidem, p. 212.

[14] Masson: Against Therapy, p. 95.

[15] Quoted in Paul Gray, ‘The Assault on Freud’, Time (29 November 1993), p. 33.

[16] Breger: Freud (Spanish edition), p. 162.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Masson: Against Therapy, p. 104.

[19] Freud, cited in Szasz: The Manufacture of Madness, p. 195.

[20] I read several quotations of Freud to Fliess on masturbation in Szasz: Pharmacracy, pp. 102ff. See also The Manufacture of Madness, pp. 189-194.

[21] Oliver Freud, cited in Breger: Freud (Spanish edition), p. 375.

[22] Ibid. On pages 244ff, Breger writes about a different case in which Freud was open minded and didn’t condemn the masturbation of Albert Hirst, one of his patients. But Freud never mentioned the case in his writings: what is known is due to what Hirst himself recounted.

[23] Freud, cited in ibid., p. 305.

[24] Ibid., p. 339.

[25] Thomas Szasz’s The Myth of Psychotherapy contains a chapter on Freud and electrotherapy.

[26] Szasz: Anti-Freud, pp. 135ff.

[27] These observations are taken from ibid., p. 136. A more detailed account of these events and the erratic story of Otto Gross appears in Richard Noll’s The Aryan Christ: The Secret Life of Carl Jung (Random House, 1997).

[28] Basaglia et al.: Razón, locura y sociedad, pp. 178ff (my translation).

[29] Ibid., pp. 179-184.

[30] Freud, cited in Szasz: The Manufacture of Madness, p. 73.

[31] Jacques Poster and Claude Quétel (eds.): “Diccionario biográfico” in Nueva historia de la psiquiatría (Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2000), p. 652, my translation.

[32] Héctor Pérez-Rincón: “México” in ibid., p. 525, my translation.

[33] In the chapter ‘The Witch as Mental Patient’ from The Manufacture of Madness, Szasz presents the positions of Charcot, Freud, Zilborg and other physicians regarding the Inquisition.

[34] Guillermo Gaytan-Bonfil: El diagnóstico de la locura en el Manicomio General de La Castañeda (undergraduate thesis, Faculty of Psychology, UNAM, 2001), p. 3, my translation.

Thank you very much, Professor MacDonald, for allowing me to publish the translation of a few pages from my book Hojas Susurrantes, which can be obtained in Spanish here (to date, only the first chapter of that book is available in English as a book).

I take this opportunity to warn you that a stalker has been impersonating me for years on racialist forums. With the exception of the articles I have published on TOO (and one or two very brief ones on Counter-Currents), I would like to warn the readers that whenever you see a commenter named “Cesar Tort” appear on racialist forums, it is not me but the impersonator (who not long ago, under another name, defamed me in the Occidental Dissent comments section, alleging that I had a homosexual relationship with a commenter I have only interacted with online!).

So whenever you see someone with my name spouting nonsense, or even mentioning my full name to say things like the above using other sockpuppets, rest assured it’s this stalker / impersonator who’s been obsessing over me (I suppose, because this man is really bothered by what I’ve written about Latin America in my blogsite The West’s Darkest Hour from the POV of race realism).

When I comment on racialist forums, even my own, I ONLY use my initials, C.T. (except of course in articles like this one, since I’m the author).

Thanks for remembering this!

Freud opposed “circumcision” which elevates him above other jews. He was also fiercely loyal to Vienna, again putting him above other jews. If the majority of jews were more like Freud I don’t think we would be having most of our current problems.

With an army of Freuds dictating, what would be the modern state of endemic child abuse treatment in the West (which isn’t very good as it is, to put it glibly)? It depends if you recognise child abuse as a serious – in that it is far more widespread than is often publicly acknowledged, as much as for the severity of the cases – problem for our coming generations, as much as for the lives of the previous. I always hope ideally solid racial/ethnocentric bonds are not made partisan on this issue (mental health).

Hello. I tried to respond to this before with a question, but I see it didn’t get through. I’ll rephrase and try again. Also, I’m aware a troll (the same guy who stalks the author of this piece) has been impersonating me here recently, which may be why the comment didn’t make it, so I have to assure reader’s that it’s me. One can generally tell by the tone of my writing and my ‘fiddly’ syntax (or my standard email address, to moderators).

My immediate response would be, do you not think that would make the problem worse? (and, I suppose, if not, why not?). It seems his positives don’t outweigh the gross negatives.

With an army of Freuds, what do you think would be the state of – endemic – child abuse, with regard to their applied treatment? I suppose it depends if you see child abuse as a serious problem, and also accept it as far more prevalent than is generally acknowledged or allowed mention of, as much as serious for the severity of the cases themselves. You’d also have to recognise how much damage these witch-doctors/witch-hunters cause. I often hope, despite the evidence on the fallout of this topic, that racial/ethnocentric loyalty is not rendered partisan on this issue (mental health) i.e. we should think as a supportive community collective will to bolster and defend our own people as whites, not as often cynical and standoffish individuals willing to betray them further. I can think of no group treated more harshly by society, whites and all, than white child psychiatric industry victims. Just to confirm, I’m not implying that latter part of my id est about you.

Thank you for a magnificent article. I thoroughly enjoyed it, and will go over it in more depth in days to come. “Blind to the obvious”: I think that encapsulates the field of psychiatry (‘inspired’ as it is to some degree by psychoanalysis) and mental health altogether. I interpreted “resistance” as being no different to their iatrogenic claims of “lack of insight”, whereby a patient calls them out on their erroneous, Pharma-fed speculations and cold, authoritarian decision making, or otherwise tells the truth about their own lives, and is thus mistreated further.

I could apply this ‘wilfully ignorant’ criticism to most of the general public also, sadly, when it comes to this issue. I think since the release of materials decimating the cruel and unfalsifiable biomedical theory, such as those of the researchers Jay Joseph, Eliot Valenstein, Patrick D. Hahn, Paris Williams, and Colin Ross (seriously unrefuted to date as far as I am aware – if anything, their opponents’ position is built on nothing but dogma, spin and endless wishful-thinking), these unfortunate and stigmatising labels of heresy against the status quo – as that is all they are, much as real emotional maladaptation still occurs in response to long-term environmental trauma, sometimes to devastating ends – should really go the way of the dodo. Except they don’t.

That’s why I think, rather than a mono-minded fixation on scientific studies and medical reports, we should instead dedicate more time to listening to the very cases (the actual lives) that Freud himself was so quick to dismiss and sweep under the rug in favour of his lucrative hypotheses. The evidence of countless suppressed testimonies, and private journals, and honest autobiographies, from the luckier patients, those not driven to complete despair and suicide, or chronic madness.

But until the fourth commandment to honour thy father and mother – presumably no matter what – is dropped, perhaps remembering Friedrich Nietzsche’s words on ‘pulling the right to Christian morality out from under one’s feet’ I sense our society (I’m thinking of whites here alone, as the retainers of Western Christian values, although this evidence applies to every race to some degree), a victim itself of these long-standing parental introjects and deep-set taboos, will continue to inaccurately mischaracterise and then psychologically murder what are, as has always been the case on the whole, victims of severe parental abuse. Perhaps it would open up a can of worms for any doubter in the process. I’m glad for the writings of John Modrow and the like, in ‘How to Become A Schizophrenic’, as much as Morton Schatzman’s ‘Soul-Murder’ and the by proxy testaments of David Helfgott in ‘Shine’ and ‘Love You to Bits and Pieces’ for elucidating me further on this matter (and indeed moving me very much).

Thanks again for your article, and thank you to Kevin for publishing it.

I’ve included a link to my small amateur website above, where, among some other miscellaneous contributions, I’ve recorded myself reading from the works of some of the various researchers and patients I think have covered this issue from a genuinely compassionate angle.

Ratibor-Ray Jurjevich’s Hoax of Freudism may be found here:

https://archive.org/details/hoaxoffreudismst0000jurj/page/n3/mode/2up

To read here without registering. https://pdfhost.io/v/wbLCVFmhwV_Hoax_of_Freudism

Thank you very much Tim (and William). I haven’t heard of this one. I’ve just downloaded it and will read it in due course. I know I’ve very much enjoyed all of Masson’s works too (even the non-psychiatric ones I’ve encountered actually, and indeed that one on Kaspar Hauser). If I may recommend one in return – sorry, I don’t have a link – which isn’t strictly on the topic of Freud and psychoanalysis, but still serves as a fair enough entry point to reviewing a paradigm shift in mental health treatment, I actually quite enjoyed Paris Williams’ book ‘Rethinking Madness’. Of course, I don’t think there’s anyone more empathetic in this field (bar Cesar’s writings) than the late Alice Miller, despite the unfortunately inclusion of her fallacious theory on Adolf Hitler, which I tend to ignore in what is otherwise a very sound body of work.

Personally, I’ve never experienced a psychoanalyst up close and personal, thankfully, but I do have some experience with the horrors of family therapy, from back when I was a teenager. I’ve covered it (and rather a lot else) in a very brutal psychiatric autobiography I wrote back at the start of the year, titled ‘Consumption’. There’s a link to its sales pages on my website. I might eventually put a PDF copy out there also.

Hello Benjamin, you seem to be a very sensitive person, which is commendable. There aren’t many like you around these days. Most people can barely form a simple sentence. Intellectual standards have declined and suffered greatly in recent years as a result of digitalization.

I could contribute on the subject of psychology, namely when it is evidence-based but also verifiable through my own experience. I collect Wiki articles on the subject I come across. Evolutionary psychologist Kevin MacDonald the opposite of “sexualized dream interpretation.”

Btw, the latest “news” about Hitler is that he not

only had one testicle, but also no sense of smell.

https://edition.cnn.com/2025/11/13/science/hitler-dna-documentary

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turi_King

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alex_J._Kay

Wikipedia category Jewish eugenicists:

“Paradoxically, he had been a student

of Ernst Rüdin, one of the architects of

racial hygiene policies in Nazi Germany.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franz_Josef_Kallmann

The “Kallmann syndrome” me

ans not only lack of sense of

smell, but also color blindness.

It is well known that Hitler did not

like the smell of meat (and tobac-

co) since World War I, and that he

himself painted colorful pictures…

Sorry Tim, I didn’t see all your new comments! Thanks for all the stuff to go through (and the compliment)! I’d be very interested to hear your psychology contributions also.

I briefly saw reference to that article the other day, or one like it. ‘Oh, here we go again!’, I thought… and noticed that reliance on PRS, having myself tried to assimilate Jay Joseph’s criticism of them when it comes to refuting genetic determinism. I forget which of his 4 core books has that material in – it might be ‘The Trouble with Twin Studies’. I suppose these new breed of impressionable genetics scientists just parrot back without evaluation the long-term lies of the psychiatric research crowd and whatever long term behavioural genetics nonsense Robert Plomin (et al.) has tenaciously re-hashed ready for another unwitting generation; another set of wildly over-optimistic claims and predictions with no evidence to back them up, as per usual.

Anyway, I won’t go on and on. Cheers again. I’m just going to go and review the JF Gariepy material. I think we have indeed fallen foul of our postmodern tools over the course of the century. I notice it myself in my diminished attention-span, courtesy of too much engagement with the fast-moving internet.

@Ben

No need to apologize, Ben.

There is a correlation between reduced attention span and multitude of thoughts (“sensory overload”). As alert and quick-thinking as you are, it can also be too much. Then there is a risk of getting bogged down, talking topics to death, or constantly jumping back and forth between possibilities without really committing to anything. Some of these people tend to talk faster than they think—or think faster than they feel.

The strong focus on logic, language, and information can cause intuitive or emotional aspects to fall by the wayside. Not because they are missing, but because the quick mind simply overshadows them. However, those who manage to combine their communicative talent with genuine depth in relationships become brilliant mediators—witty, clear, agile, and convincing.

It’s best if you suggest a topic and I’ll respond to it. By the way, you can also use AI to check your own comments that you are unsure about (omit any potentially political or ideological “hot buttons” or replace them with “inconspicuous” ones) in order to find a sense of proportion and balance.

In my experience, the average “human” is not interested in specific expertise. One only needs to reflect on oneself. We are primarily interested in entertainment, in the “new” (i.e. previously unknown), but above all in the lighthearted, easygoing, and funny. We like to view this intolerable world from an ironic perspective that allows us to build more distance from it.

@Ben

One colossal insight is that practically everything

(even the truth) can be “refuted.” Therefore, the

truth cannot be captured with a landing net, but

rather in a holistic statement that encompasses

and addresses our brain, our knowledge, our emo-

tional perception, and our experience. The reduc-

tion of our senses to the digital realm is therefore

the devil’s work of our adversary and mortal enemy.

Year ago I reads Jeffrey Masson’s deconstruction of Freud. Masterful.

Somebody should write up the Jewish angle on Freud…hatred of Western society and Christianity/Culture.

Freud seems to be so dead today that only a few decomposition fumes remain from his corpse. I knew a Jew-Freudian a few years ago who was one the nastiest characters I have ever met.

Have you read the chapter on psychoanalysis of Culture of Critique? Masson is cited among many others.

Unfortunately, in Latin America Freud is still taken seriously in some quarters, and I’ve heard it’s experiencing a resurgence in Germany. Speaking of Masson, I forgot to properly include the bibliography information for the book mentioned.

Ultimately, while I have been following César Tort since the fall of 2015, adore his exterminationist ideology, his anti-Christianity and desire to settle Japan with Aryans, I can’t take seriously his constant nagging about child abuse. Any rational person can see that Asians abuse their kids much more, and yet they don’t produce many traitors (see Aung Sang Soo Kyi, Kim Yo Jong, Sanae Takaichi for the cases of even women who don’t turn traitor – that’s the difference a simple lack of Christianity makes!). I’d rather go with Devon Stack’s position that schizos should be shot because they’re genetically inferior. In fact, Chechar’s focus on nurture as opposed to nature is by definition leftist and pointless. But then, he also thinks Gaza vermin are being genocided, and that Russia is winning the war – both utterly deranged takes, so figures.

We meet again!

Why are we automatically considering traitors and not just very hurt people? I think the aetiology of traitorhood is multi-faceted, much as yes, as could later make sense (even to you), I’m still wondering if abuse plays a part, even if not the whole. A lot of child abuse victims I’ve met aren’t political in any sense, and are just switched off normies (unless we’re going for the, ‘anyone who isn’t right is left’ binary)

Where is this fabled genetic evidence for schizos? (please, nothing tiresome and over-familiar)

For a very simple example, it’s not common to see it before a certain age, say, as a baby. Also, most schizos don’t have children. I know we could say it only ‘switches on’ past a certain developmental point, but when that coincides so strongly with the background knowledge of severe abuse around that same point (as well as being equipped with a working model for exactly what this abuse does to the mind/brain), it’s suspect to rule out a gathering connection a priori. My second point acknowledges that it’s odd it’s so prevalent, given the heredity issue. We’ve totally forgotten environmental confounds, or ignored them, because the Duttons of the world are cheaper on the mind, and tell you what you want to hear.

Where is your evidence-based argument beyond opinion-making and chucking of the ‘leftist’ trope at anyone who isn’t a dispassionate and depressive stone? Before we noticed leftism, was anyone ever nice, or perceptive, to be glib about it? Maybe it’s just something we – some of us – have in common, as people, as opposed to being solely in either trendy political camp.

What is nature’s, I put down to nature. I am surprised each day at what is not in that category though, speaking as someone who formerly included much more.

I know this thread won’t last forever, I just wanted your most contemporaneous accurate research to mull over, so I can see, as usual, what particularly dead end you’ve gone down and don’t want to back out of more clearly. I may not respond again, but I’m curious.

I already think you’re a race-traitor, as we’ve established, given the evidence (I’ll leave aside speculations), not that I know it bothers you one bit to know that.

You seem to go with what pleases you (and what means you don’t have to recant anything; not a drop) rather that the larger body of what is there to empirically review, and what, if there were more who could care to peruse it, or just, you know, ask, makes far more academic sense. I’m sorry you’re not right. I’m sure it’s not good on the mind. I’ve given up trying to put it to you in general.

Now, I ask myself wearily, how many ways can this be doggedly cherry-picked for retorts?

“Professor” Dutton recently revived the (long-disproved) theory that “left-wing or liberal women are infected with toxoplasmosis transmitted by cats, which essentially shuts down their common sense.” Mr. Dutton is clearly treading in the shallow waters of nonsense here.

I myself know a lifelong cat lover (now over 80 years old) who is an energetic opponent of immigration and anti-feminist. Savitri Devi was also a lifelong cat owner. Perhaps evil “white supremacist” Gariépy has something substantial to offer with his book?

https://rumble.com/v71q7u8-rumble.comnightnation-guest-j-f-garipy.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Fran%C3%A7ois_Gari%C3%A9py

https://odysee.com/@JollyHeretic:d/toxoplasmosis-owning-cats-turns-women:b

Oh dear… every time I think he can’t get any worse…

I ended up writing a slim, moderately intellectual self-published (it shows) book in 2024 titled ‘The Less Than Jolly Heretic’, with Dutton firmly in mind for the title. It hops about all over the place, but I hope he could bring himself to hear of it one of these years. I doubt that though. Credentialism might break loose – I’m more of an armchair philosopher. I emailed him once in a total state (psychotic with grief and shame in the background), and regret that I couldn’t convey my disgust that Christmas evening at his lazy confirmation biases and sheer lack of rigor sensibly (a real one for ‘rearranging their [Conservative] prejudices’). He’s more like an indolent school boy new to hearing of ‘hard science’, but deciding demagoguery is slightly more lucrative, especially on the ego, having roped in a fresh new congregation of all the usual ignorant morons who fall for the right cheap and nasty key phrases and faulty concepts necessary to back him up in a symbiotic (and yet ultimately parasitic) cult relationship. He’s so crap at what he does (bar the vaudeville Oxbridge theatrics) that at times I simply couldn’t conceive of him as being anything other than a subversive ‘bad actor’, much as, oddly, I know he’s not.

This is only my secondary site, and certainly isn’t finished, but I’ve got a few pieces on here that might hold their interest (a little bit – despite a few subtitles spelling errors here and there, and not much effort with camera settings on the vlogs, and of course, the question of what happened to all my teeth): https://benjaminpower92.wixsite.com/spare-videos-blog

P.P.S. sorry, I think this’ll be my last comment. I don’t want to be seen as ‘spamming’ this site. Thank you again for the above Rumble link. It’s true, I haven’t read ‘The Revolutionary Phenotype’ (though will be). I partially agreed with him. I’d say about 2/3-4/5 of it.

I’m left questioning how much we do understand Evolution though. I usually adopt a soft determinism based on Orch OR melded to some of the Theoretical Biologists. There are a few of the Stuart Kauffman books that appeal, as well as ‘Evolution “On Purpose”: Teleonomy in Living Systems’ by Peter A. Corning et al. (who also wrote one I’m currently working through titled ‘Holistic Darwinism: Synergy, Cybernetics, and the Bioeconomics of Evolution’) as much as ‘The Tangled Field’ (on the classic research of Barbara McClintock, which is an interesting springboard read, if incomplete). It’s not to be confused with Communist Lamarckism. I think it ties in well with the partially-free i.e. cosmologically limited, positions of Philip Goff, and Thomas Nagel’s recent ‘Mind & Cosmos’, something I tried (and I think failed) to encapsulate in a recent amateur article titled ‘Orchids in Amber’ (which I’ve recorded for my website – although it’s only a draft, and the original document alone features the references).

Rather than a supreme reliance on and capitulation to random mutation (which, after all, isn’t too common), I wish more emphasis was placed on original Mendelian genetics with regard to hybridism and ancestral miscegenation. That’s a side point to the above though. ‘Archaeogenetics’ has always failed to convince me. Phenotypes display genotypes anyway, in a more natural presentation that digging out the DNA tools at all.

I think for science to be truly impartial we must get over the hang-up of worrying if what we think is ‘leftist’, as if anything the leftists have simply co-opted an arbitrary academic position (at times – I mean, obviously some things are legitimately lefty) which may be correct regardless, and thus just unfortunate that it’s them who try to claim it as their own. Another reason I wish Dutton has not got to the average right, as he’s set them back with his brainwashing by at least a generation in my estimation, and worked very successfully at closing their minds. I personally think it’s impossible to reverse that on the whole now.

Hello Benjamin, I already visited your website! You can prevent yourself from “getting lost in your thoughts” (and subsequently worrying that you might “stand out in an unpleasant way”) with a simple technique. Ask yourself questions like:

1. “Does anyone (here) really care about this?” 2. “Am I making a difference to the general mush on the internet?” 3. “What points do I need to get across briefly, and what should I leave out because it’s ultimately irrelevant or too long-winded?” 4. “How can I entice the reader to want to hear my thoughts?”

Everything should be clearly laid out and inviting to read. Lighten things up with humor, sources (videos, links), and paragraphs. Overcome self-doubt or fear of rejection. Write as if you want to enjoy it yourself.

Well, as for Dutton, he’s practically “self-explanatory.” One thing is certain: he has no shame about attracting unpleasant attention. As we can see, this indifference and self-assurance can also be a disadvantage if you are unable to exceed a certain level of persuasiveness.

@Ben

A funny person is forgiven (almost) everything! And, moreover, that’s actually the healthiest attitude one can have toward life. You should always have several irons in the fire, too. That makes you independent. If someone drops out or acts stupid, it doesn’t matter at all to leave them out.

In general, comments should be worded so universally that they could basically stand as-is in thousands of forums, regardless of what “topic” is being debated. They should be so funny that they’ll still make people laugh even in 10 years.

With time, you’ll see that through your cheerful, playful way, you trigger positive feelings in others. And that, in turn, makes you even happier than you already are.

In a fundamentally negative world, this is how we can generate a positive feedback loop within the scope of our options. People see that they can look at all this political nonsense from a totally sarcastic perspective, too.

In my opinion, that’s the only thing a good writer can actually achieve. Wanting to “change the world” is an extremely foolish ambition that will only end in frustration, and that’s not at all what we want.

Finally, you’ll notice that acting this way also shifts your emotional baseline, and irony becomes part of who you are. And since people usually want to feel at least a bit better, you’ll seem intellectually attractive, inspiring, and stimulating—you’ll give them a little moment of good times.

There are more than enough gloom-mongers and doomsayers in the world, that’s for sure. But this isn’t just about silly goofing off. You can deliver a message you consider important via humor, using it as a kind of lubricant, while subtly weaving in a political point.

@Ben

Something importent is more to say: Sensitivity is a quality, but it should generally remain hidden behind a protective armor. Not everyone “recognizes” these qualities, so don’t make them dependent on your environment!

Otherwise, certain people of low character and mindset in particular (“the mob”) will perceive you as a kind of “vulnerable prey.” Therefore: Apologize rarely, but stand behind your contributions like a snarling guard dog!

Never make yourself unnecessarily smaller than you are! Your problem is that you are not aware of your own worth and how to use it to your advantage.

You can use your mind to initiate a self-healing process in your brain. Consider what you think, whether it is meaningful, helpful, and useful. Like a stutterer who learns to speak fluently. As a former stutterer, you can become the best rhetoric coach, turning a former weakness into an outstanding strength. In the future, your brain will automatically filter out superfluous thoughts (which lead to superfluous emotions).

In response to my own comment, yesterday I read the two Wikipedia articles “Irony” and “Sarcasm.” Humor is (almost) always at the expense of others, who (unfortunately) never find out about it themselves. Of course, it goes without saying that one should not speak ill of (innocent!) people who are actually suffering or in need.

Under the section “In religion,” we find the following lines (which are probably meant to be interpreted as a kind of “criticism”), linked to the source that follows:

“The Buddhist monk Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu has identified sarcasm as contrary to right speech, an aspect of the Noble Eightfold Path leading to the end of suffering. He opines that sarcasm is an unskillful and unwholesome method of humor, which he contrasts with an approach based on frankly highlighting the ironies inherent in life.”

https://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/thanissaro/speech.html

It is simply ridiculous for someone born as Geoffrey DeGraff (who, interestingly, still wears glasses, invented by representatives of his race) to hang a Thai rag around his neck, give himself the Thai fake-name “Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu,” and pretend to have a false identity and lifestyle that has nothing to do with his culture.

I see no reason whatsoever to spare Mr. DeGraff from this ambivalence, which immediatelycatches the eye of those who seek truth and recognize contradictions! I see it this way: The truth is something people must be trusted to face.

If the American DeGraff believes he can disenfranchise us with his appropriated fake “wisdom” and act as an “authority” proclaiming truths, then he is sorely mistaken! Look at him, this begging idiot who has the impertinence to disguise his physical laziness and moral dishonor as a kind of “holiness”!

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/3f/Ajaan_Geoff_Almsround.jpg

think it’s perplexing that one of the most lucid racialist thinkers of this century is a Mexican, Mr. César Tort !

In a future White Homeland, we pure Whites should give citizenship to non-Whites who are fighting gallantly for White preservation.

They deserve a place within the borders of the White ethnostate.

It will be more than enough to deprive these heroes from the right of reproduction in the Homeland.

Anyway only in the first generation will the ethnostate allow working together with the heroic mudbloods who put their lives in danger to save Whites from extinction.

I once read an article or perhaps watched a video that showed Freud to be quite sympathetic and even admiring of the Nazis.

Hi Lana,

What interests me myself along those lines is that Hitler and his National Socialists themselves implemented a policy that, among other categories of disability, addressed psychiatric patients, known officially as the Aktion T4 program (named after the site at the Tiergartenstrasse 4 villa in Berlin, set up at the start of 1940). Unfortunately, due to the prevalence in his day of this sort of entrenched 19th Century thinking, he did not inhabit the historical conditions or inherit the intellectual mantle to have known any better, and thus his policy was misguided. I don’t hold it against him; it’s understandable. I think a further argument for my point above to someone else that severe trauma instigates ‘schizo’ madness is that in Germany at least, pretty much the entire psychiatric population, regardless of race, were sterilised (or otherwise subjected to involuntary euthanasia), and yet by not long after the war, in the same generation, the number of schizophrenia (etc.) cases in German was again very high, and on from there to the present, lending some weight to the environmental trauma hypothesis, even if we still should evaluate the specifics of that (their compound de-Nazification trauma, and bitter war trauma, atop home life abuse from parents who were themselves traumatised). This is as best I remember it off the top of my head by the way.

Now they are reviving the Asperger issue. Jews in particular have been campaigning against him for years, effectively labeling him a “mass murderer,” including Joseph Buxbaum, Edith Sheffer, Steve Silberman, and Jonathan Mitchell (crypto-Jew).

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2025/nov/16/his-research-on-autism-was-compassionate-how-could-hans-asperger-have-collaborated-with-the-nazis

Not even close, he indirectly

regarded National Socialism

as “personification of death

drive,” while seeing himself

as “divine offspring of Eros.”

Just the usual Jewish hubris.

I’d bet that this “Kevin Graeme” guy, who commented above, is the same stalker I mentioned in my first comment; the one who, on The Unz Review for example, always mentions my full name, or impersonates me and calls me “mudblood”.

But I wanted to talk about something more important in this comment. Yesterday I uploaded a video, recorded in Spain, with English subtitles, about the Freudian follower I mentioned in the article. It’s the first time I’ve shown my adult face to a racialist forum (and I’ll be uploading other subtitled videos soon).

The video explains the autobiographical phrases that were not detailed in the above article.

Millions of white children will hate your guts if you restrict their diet to rabbit food. You can’t force people to eat food which they do not like. We are omnivores. That is how we evolved. If you deny that, then you’re just as bad as the biology-denying Left. So what are you gonna do, César? Will you be putting a gun to the heads of millions of children, forcing them to eat your vegan slop?

Oh, and those Maxfield Parrish paintings aren’t very good. Some of his women almost look like they have afros.

Oh, drop it would you? Remarkably hyperbolic. You know very well your point is dictated by your spoilt ‘training’. How do you even know that about what they would think, and in what numbers, and how could you know that?

We are not forced to utilise every last idiosyncrasy of form we have evolved (beyond your slander, so what if the leftists are also vegan? They also have two feet usually, but I don’t see you amputating yours in disgust. Remember our former point on Muslims for this analogy. I remain an ethical vegan National Socialist, in the manner of Savitri Devi). We are not advocates of the unfalsifiable, poor choice-making cop-out that is hard determinism. Your ‘forced by nature’ is a fantasy that translates to a doubled-down lack of will. You simply don’t want to. You simply cannot, off the cuff, pathologise everyone you disagree with.

You seem to work from the same (I want it to be true so it is!) perspective as the other guy, and you’ve been put wrong on this before. So far, governments can quite successfully, on the whole, force people to pay taxes, etc. See that as a working analogy for it.

For someone who has rarely eaten vegetables and fruits, etc., (maybe a few times as a resisting infant; a thoroughbred Little Lord Fauntleroy if what you are now is anything to go by), you seem very knowledgeable on their tastes and qualities. The selection is in fact vast.

I think they’d hate your guts more if you *genuinely* brutalised them, but I know from reading you that you deny the very damage of legitimate child abuse consistently, and in fact advocate for it at times, much as you seem to deconstruct it and give it new meanings to fit your mono-minded purpose over this issue. I would say, raised like that; familiarised with that (and certainly not spoilt), they wouldn’t naturally have a problem with it, and indeed some have the mental faculties and empathy level to choose that route anyway from my experience.

We did this debate to death at TWDH. The issue is not even primarily dietary veganism as ethical veganism (I personally can cope with vegetarianism as a stepping stone), and you refuse, for reasons outlined above, to acknowledge the ethics of animal cruelty (beyond a few clueless and assumptive platitudes), making you both quite disturbing as a person, and also not particularly worth arguing with, much as I just have.

This may not succeed, and that isn’t set in stone, but it’s not incorrect for ethical reasons, as you would desperately like it to be, and surely not alone in that, if still somewhat of an outlier in terms of your sheer, petulant indifference to the horrors of the modern food system. Anyway, sorry for going off-topic.

P.S. I can’t speak for César, but given your general lack of perceptiveness and feeling, I wouldn’t trust you to judge Art either.

Because it’s basic biology. Humans are natural omnivores. I don’t subscribe to any metaphysical woo. I don’t believe there is anything more to life than what we see. All of your ancestors ate meat. They weren’t a more evolved psychoclass, and neither are you. Veganism is the same self-abnegation promoted by Christianity. It has its origins in Seventh Day Adventism. These lunatics actually think that the lion can be conditioned out of his natural carnivorous inclination and lie down with the lamb.

We pay taxes because everything would grind to a halt if we didn’t. It’s part of the social contract. If we don’t eat according to the diet we evolved on, our body degrades. Put simply, our ancestors wouldn’t have eaten meat if they didn’t need to. In the same vein, if the brain was not fundamental to consciousness, we wouldn’t have one. Ergo, humans eat meat out of necessity, and there is no such thing as a soul. It isn’t up for negotiation.

No, we didn’t debate this to death, because César is quite fond of censorship. Anything he can’t answer, he censors. I completed my essay regarding a question he, on numerous occasions, refused to answer, because the answer was embarrassing for him. You can read it here: https://arnoldtohtfan.substack.com/p/the-historical-absence-of-feminine

As an anti-natalist, I have defied the biological programming that most humans share. The difference, of course, is that I’m not going to starve if I don’t reproduce. Forcing children to eat a diet they did not evolve to eat is child abuse, so don’t talk to me about unnecessary suffering. Nothing necessitates the creation of new humans. It is a vanity project for César, nothing more.

Most vegetation is full of toxins, hence why we don’t like the taste of it. It’s alright for you, though. You can always go chew more gristle off your forearm. But the rest of us aren’t that nuts, and I for one am not going to make my life any harder than it already is. As an autistic man, my diet is restricted enough, thank you.