Trial by Jewry: Sapiro vs. Ford

Henry Ford’s War on Jews and the Legal Battle Against Free Speech

Victoria Saker Woeste

Stanford University Press, 2012

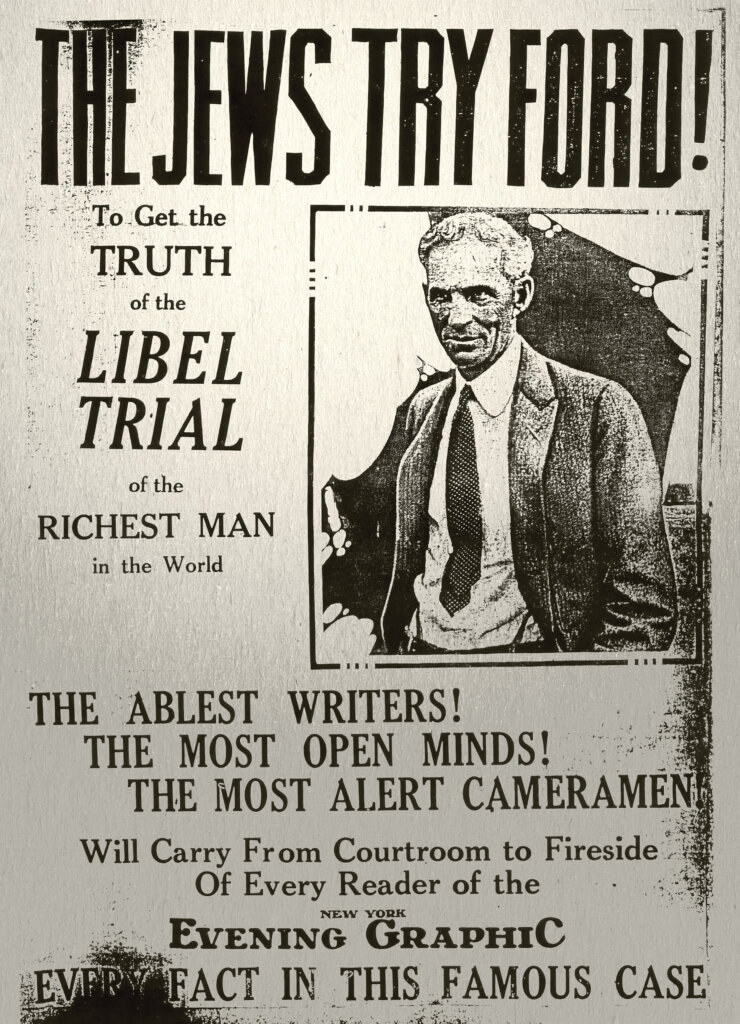

“‘The Jews Try Ford!’ headlined a banner advertisement in the New York Evening Graphic” (ibid.).

On the evening of March 27, 1927, Henry Ford was doing what a lot of other Americans were doing, driving home from work. Like many of his countrymen, he was driving a Ford. However, as he owned the company — possibly the most famous brand-name in the automotive industry even today — Mr. Ford’s customized coupé was a little out of the ordinary for the marque. With a prototype manual transmission and extra gears, bullet-proof windows (against his wife’s fears of kidnapping), and a top speed of 75mph, it was rather different from the famous Model-T, the car anyone could have in any color as long as it was black. In fact, Ford was returning from a late night at his River Rouge plant, just outside Detroit, where he had been working on blueprints for the car with which he wished to replace the “Tin Lizzie”. Chevrolet and GM were already out-selling him in the everyman market.

Ford took State Route 12 home, connecting as it does Detroit and Ford’s home town of Dearborn. Ford had just crossed the Rouge when another car came up quickly behind him and ran him off the road. The only thing that saved Ford from an impromptu car-wash in the river — and quite possibly death — was the chance placement of a tree. But Ford was alive, albeit dazed and concussed, and was hospitalized until the beginning of April. Under normal circumstances, for the CEO of such a large company, this would have been an inconvenience, and Ford could have delegated his duties with confidence. But Henry Ford was about to take the witness stand in one of the trials of the century: Sapiro vs. Ford. This was ostensibly a libel trial, but its overtones make it clear that what was really on trial was anti-Semitism.

The day after the crash, a statement was made by Harry H. Bennett, Ford’s personal bodyguard and a part of his famed “secret service”. Mr. Ford’s car, said Bennett, “was sideswiped by a hit-and-run motorist driving with one arm about a girl or slightly intoxicated”. The papers, however, stirred up a conspiracy. “Plot to kill Ford suspected”, thundered the New York Times, with other titles following suit. By April 1, four days into the trial, Ford was also saying that the incident was “a deliberate attempt to kill him”. Who would attempt such a thing? Ford certainly had enemies.

A short book with a long title, Victoria Saker Woeste’s Henry Ford’s War on Jews and the Legal Battle Against Free Speech [Ford’s War], gives an extended court report of Sapiro vs. Ford in which she draws each character in the context of the central question around which case revolved. In most cases of this sort, this would be libelous intent. In Sapiro vs. Ford, the invisible and yet-to-be-codified legal principle which hovered ever-present over proceedings was anti-Semitism. This case came as close as any to establishing whether or not “anti-Semitism” had woven itself into the American legal tapestry as far back as the First World War in the same way it has today in the United Kingdom, where only Jews are actually protected by legislation (although this may soon by joined by Islamophobia laws).

This was not Ford’s first time in court. Ten years prior to Sapiro vs. Ford, he had been an involved in a trial concerning the value of Ford dividend stocks, and he had already been involved in one libel case over an article supposedly libeling him in the Chicago Tribune. This was “a dress rehearsal for the Sapiro case a decade later”. Ford had become involved in the “Peace Ship”, a gimmicky environmentalist stunt which Ford sponsored in order, the newspaper claimed, to garner public sympathy for his supposed “good works”:

“The Tribune’s position was that Ford’s pacifism endangered the national welfare and made him fair game for editorial comment”.

Ford won, and later found the experience invaluable when Jewish lawyer Aaron Sapiro took him to court in 1927 over allegedly libelous editorial commentary of his own. A Ford-owned newspaper, the Independent was launched in 1919, intended as a political heavy-hitter with serious literary pretensions. The first issue featured contributions from well-known American poet Robert Frost and Hugh Walpole, a British novelist, critic, and dramatist. Ford also began what the author describes as a new war, “a war on Jews”. Sapiro was joined by Louis Marshall, a Jewish lawyer and anti-immigration restriction activist who saw anti-Semitism in all walks of life and was prepared to take on a man at the top of the heap.

As well as being a lawyer — as was his brother, Milton — Aaron Sapiro started and owned farm co-operatives, and “his fame and popularity among farmers made him the nation’s premier cooperative organizer during the 1920s”. Over-production and low prices, however, led to lower profits and excess supply, and many of Sapiro’s leading producers buckled under financial pressure. It was precisely Jewish influence on price-fixing and syndication that Ford’s editorial line sought to expose — the hidden hand of Jewry at a localized level as well as the “International Jew”, which became the title of a later and more specifically targeted series of articles in Ford’s newspaper. Sapiro’s business failure shows, if nothing else, that Jews don’t always come out of business enterprises with full control. They have yet to fully tame the market.

By 1927, and Sapiro vs. Ford the Independent had lost $2 million, but it didn’t bother the car-giant. Ford wanted the paper to become “the common folks’ primer on American culture, literature, and political philosophy”. But, together with his editor, Ernest Gustav Liebold, Ford was using the publication for another purpose, to expose what he saw as “the disproportionate influence of Jews on politics, culture, entertainment, diplomacy, industrial capitalism, and the state”. It was time, Ford believed, “to take on the Jews”:

On May 22, 1920, the Independent launched [an] antisemitic series, purporting to reveal the role of the ‘International Jew’ in world affairs. In ninety articles that ran weekly for nearly two years, the Independent excerpted and recapitulated the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, adapted and Americanized for its intended audience.

The Protocols had only recently arrived on American shores, Ford having had a copy sent from Europe shortly after the Tribune case. Nowadays, even for those some way out on the political Right, the Protocols bear the same relation to history that a graphic novel today bears to English Literature. But its effects were far more incendiary a century ago, and to implicitly bracket “the elite of American Jewry” in the same series that highlighted the Protocols was intentional, claimed Sapiro. This is anti-Semitism by association.

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion is often referred to as a “forgery”, but it was not. A forgery implies a primary text or image which has been illicitly reproduced, but there was no such primary text of the Protocols. More likely, it was a literary hoax, like Thomas Chatterton’s “Rowley letters”, supposedly written by a Medieval monk, or Nietzsche’s supposed confessional, My Sister and I. But the Protocols has always done great service for Jewry, and it might even be suggested that it was produced by Jews as something of a literary false flag. Jews do not wish to see an end to anti-Semitism because the term functions to bind Jews together in confrontation with a hostile world filled with irrational hatred. On the contrary, they need it just as Blacks now require White racism in order to explain their failures.

The rise of anti-Jewish feeling in Germany had even led to the coining of a new term, ‘anti-Semitism’. Now, of course, this wearily familiar charge is equated with violence or incitement to violence, without having to examine Jewish behavior or a serious assessment of Jewish power and influence. In the America of early last century, there was more of an acceptable social itch over Jewry, as an excerpt from a letter to Time magazine of the period illustrates:

Why can’t the Jews leave us alone? Why, when I, and people who feel as I do, make up a club, an association or an organization, do a host of Jews immediately attempt to crash the gates and enter into our midst? … Why can’t they leave us alone and form their own clubs, hotels and associations where no Gentiles will be allowed? If they did this I believe there would then be no reason for any Anti-Semitism.

However, as we are all too aware today, that is not the way Jewry operates. Where there is organization, particularly among moneyed American gentiles, there is an opening for influence and potential gain. This is why they cannot “leave us alone”, and this infiltration was at the heart of Ford’s editorial campaign.

The first wave of resistance came after the American Jewish Committee (AJC) published a rebuttal to the Protocols in 1920, a rebuttal that emphasized Ford’s innovative distribution network of selling the Independent on the streets:

By using criminal libel as the legal basis for banning sales of the Independent on city streets, public officials hoped to serve two aims at once: assure their Jewish constituents that they took Ford’s attack seriously, and head off the threat of violence on the streets.

How like today in the UK, where Britain’s police forces — or “services”, as they have now been pacifically re-branded — act to “prevent community tensions” in the wake of any perceived slight, which essentially means stopping Blacks and Muslims from reverting to their nature in the public square, as they will if unsupervised.

Ford won the case, but was awarded only nominal damages. The real talking-point of the whole trial became Ford’s apology, discussed by the whole nation and not just its media. Edwin Pipp, one of Ford’s trusted aides rather than the Dickensian character, immediately told the press that the apology had been on Ford’s initiative and was Ford’s alone. Perhaps, he mischievously suggested, Ford just “wanted to pull the desk from under one of his employees”. Business is a dirty game, and businessmen fight dirty in the courtroom too, as Donald Trump has shown recently.

But why did Ford apologize? Did Ford fear that his Jewish workforce would lay down their tools and walk out on him? Unlikely. He had made a point at the trial of emphasizing the number of Jews he employed, and there is no suggestion that Ford was a bad boss in terms of working conditions. Jews wouldn’t buy his cars? Big deal. They were three million consumers out of 118 million. Was Ford eyeing a Presidential run, and thus seeking to placate William Randolph Hearst, as at least one paper suggested? The author gives the impression that casual anti-Semitism was quite acceptable in all walks of life in America at that time — “the day’s genteel anti-Semitism”, as Woeste puts it. Ford’s editorial campaign against Jewish influence might have been not problematic but rather an implicit campaigning point, albeit a whispered one.

While Marshall and the Jewish lobby saw Ford’s apology as a humiliating climb-down, it was a far shrewder move than that. It cost Ford nothing, saved him from the time-consuming business of further legal entanglement, and bound him to nothing, as it was made in the public arena and not in a courtroom:

Ford used the gesture of an apology as a dodge, not just to extricate himself from the lawsuit but also to give the appearance of taking responsibility without actually doing so.

Ford also closed the Independent at the end of 1927, and perhaps he felt both that he had made his point, and that he was now free to go further:

Although his printed war on Jews ended, Ford controlled the terms of the ceasefire, which left him free to spread his antisemitic beliefs throughout the world by other means.

But he never did go further.

Just as is common practice among Jews, litigious or not, Ford could make an insincere apology and any shame attaching to it would be exonerated. Elon Musk went to Auschwitz after being criticized for saying the ADL was an anti-White organization. Was this a sincere apology? Who knows? Blacks and Muslims in particular do not typically give apologies (Ye’s recent apology to the Jews is an exception) because it represents a loss of face, anathema to both cultures in a way that is foreign to Whites. Ford’s apology was perhaps a move to force a stalemate, and leave Marshall and the Jews he purported to represent with little in the way of legal weaponry:

Whether Marshall would be able to counter that spread [of anti-Semitism] effectively would depend on his ability to use the apology to force Ford to act in ways that the legal system, for all its formal authority, failed to compel him to do.

Sapiro vs. Ford featured two of the four central pillars of anti-Semitism, what Jews themselves notoriously refer to as “anti-Semitic tropes”. Ultimate Jewish financial control of industry (centering on the local farm co-operatives) was obviously at the center of the case, and the charge that Jews act for international Jewry above the interest of country or company was implied in the debate over whether “Jew” and “Jewish” were used pejoratively, and whether libel of Mr. Sapiro and other named Jews could be extrapolated as being libel of an entire race. The other pair of “tropes” was not featured, including the rootlessness of Jews and the untrustworthy nature of their nomadic, stateless existence, was of no real relevance. The final pillar, however, was absent for a very obvious reason.

The connection in the Jew-critical mind between Jewry and mechanization featured heavily in Heidegger’s Black Notebooks, a collection of essays on Heidegger’s working notes, and which I reviewed here at The Occidental Observer. The Jews exploit mechanization in its literal form, but also as an analogue, a working model, for how societies should be run, or at least how they should be run for Jewish benefit. Technocracy is simply the most efficient way to coerce gentiles — and the “meaningless Jews” who are collateral damage for those at the top — into both keeping Jews in the position of world hegemony, and never criticizing Jewry. Heidegger, in The Question Concerning Technology, says that man himself has become a “standing resource”, in the same way as wood or iron ore. Like the citizenry in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, humans have become cogs and switches, just another part of the machine. But Ford could hardly blame a Jewish goose for his golden egg because he was equally debarred from the “mechanization trope”, given that he made his fortune with both literal mechanization, and the technocratic analogue of specialized labor. Frederick Winslow Taylor was the man who persuaded Ford to stop a few men building one car, and instead have each man doing one stage of the job on what came to be called a “production line”.

Sapiro vs. Ford also brought the whole circus of a high-profile American court case to bear. As well as armies of lawyers in different locations nationwide, there were teams of journalists vying for the big story of the day. It is a pleasure to read excerpts from the American political press of the time. Journalism used to be an art before it was reduced to a technocratic tickertape of stringer’s clichés. There were platoons of private investigators looking into both Ford and Sapiro, as well as the jurors, and then there were the public, always drawn to these courtroom jousts as they would be to a major sporting event. Only this time a Jew was involved; this was as close as America would get to its own Dreyfus Case.

The Jewish lobby did not make a special case out of Henry Ford, but rather cynically used another defamation case to complain bitterly about discrimination. The Daily Worker newspaper had published a poem bitterly critical of America:

Ford’s newspaper merely insulted a race. The Daily Worker’s poem conjured offensive images and impeached the nation’s character. American courts had no difficulty finding that the latter was obscene on its face, whereas the former was immune to criminal prosecution.

The suggestion seems to be that to impugn Jews in print should be treated at the same level of punitive legal severity as treasonous editorial content, an extraordinary constitutional equivalence. And both the implications of Ford’s supposed libel, and anti-Semitism in print in general, also show Jewish solidarity, a type of “collective responsibility” for the entire race. And one of the drivers of this false extrapolation is very familiar to us today.

The ADL (Anti-Defamation League) of B’Nai B’rith was formed in 1913 after the arrest of Leo Frank, whose case was — as we might say today — weaponized:

[Frank’s case was] a rare exception to the general pattern of American antisemitism, which remained a localized phenomenon that did not lead to widespread physical violence against Jews. Yet American Jewish leaders had grown nervous, uncertain as to how antisemitic sentiment would manifest itself in American political and civic life.

Alternatively, one might argue that the Jewish lobby saw a chance to extrapolate a single case to be an incitement against a whole race. This is a response we know today through long experience, and effectively covers all non-white or Semitic ethnicities. Thus, to single out Somalian daycare fraud is to impugn every Somalian, to point out the existence of the UK “grooming gangs” is to slander all Muslims equally, and to make any criticism of a Black is effectively a portal to racism against each and every non-White. Strange bedfellows though they may be, the Jews share something in common with the Hell’s Angels and The Church of Scientology; attack one, and you attack them all.

Ford’s War is partly history, partly an examination of the apparatus of anti-Semitism, and partly a detective story. For an amateur historian such as myself, desperately trying to play catch-up after years of inattention, Ms. Woeste’s book is the very best type of history. The broad-brush strokes are essential, of course, but those historians who take a moment in history and dissect it, looking at its fine detail forensically, and teasing out the range of its effects, breathe life into the subject for the layman, as well as posing, in this case, one of the most difficult questions currently in existence: why is it not legitimate to criticize Jews?

The point of libel law is to protect named individuals from ungrounded and defamatory attack, usually in print. Now, of course, libelous intent has been re-vamped as “hate speech” across the West, and Sapiro vs. Ford can be seen as a key driver of this mutation. Sapiro vs. Ford revolved around extrapolation: was criticism of one Jew implicitly a criticism of Jewry? Historian Norman Rosenberg described the point of libel law at the beginning of last century as being “to protect the best men”, and it was also clearly intended to provide financial redress in individual cases, which is part of the disincentive against suing someone well off. Imagine how it would sting to give money to a very rich man. But the portal to any defamation case in these pre-TV times was the press and, by extension, journalism itself.

The American courts were alive to what they perceived as the threat of sensationalist and defamatory “yellow journalism” to prominent individuals — as it was seen to be, as in today’s “gutter press” in the UK. But what happened during Sapiro vs. Ford changed the focus from individual to race of individual:

To restrain the power of the ‘new journalism’, which prized exposé-style reports into the private lives of public officials, public employees, and persons with established celebrity reputations, state appellate courts upheld damage awards in cases where juries believed newspapers had gone too far in holding such public figures to ridicule. ‘Insurgent political movements’ such as populism, with their own newspapers and networks, ‘sought to wrest both the terms and the channels of political debate from the hands of a new political-corporate elite’. During this time [i.e., during Ford’s first, 1916 libel trial], legal theory developed a ‘scientific’ law of defamation that helped judges protect the reputations of ‘honorable and worthy men’.

This is analogous to our current situation, and with the same drivers behind the scene, forever coming up with technocratic schemes to prevent speech critical of what the British now call “protected categories”. Whenever someone develops a “scientific” law of anything which is not a natural object of scientific enquiry, technocracy has come to town. “Science” should not be trusted to operate outside the lab.

Sapiro vs. Ford was, perhaps, the first hate-speech trial. Such trials take place across the UK on a daily basis today (some estimates now put the annual arrest rate for online commentary up from 12,000 annually to as high as 14,000), so the British are among the first people becoming used to lawfare against people who are neither rich or famous. The legal principle animating Britain’s hate-speech laws is analogous to the ideal EU form of legislation; Rather than everything being legal except what is specifically deemed illegal, the reverse is the case. Everything is illegal unless a legal dispensation deems it otherwise. I want to avoid saying say “let that sink in”, but do read and inwardly digest. Because this is a link in a chain another link in which is Sapiro vs. Ford.

In 1927, however, the new legal principle at stake — that of libelous extrapolation — had not been written into national law, as it has now in the UK, as noted. Sapiro vs. Ford was largely a spasm in the Jewish body politic rather than any genuine moral crusade. Nevertheless, and despite winning the case, Ford has been what is today called “demonized” by the Left. It is not the court records or the verdict in Sapiro vs. Ford that color today’s perception of Henry Ford. It was the ideological company he was seen to keep. Before World War 2, Hitler was known to be a great admirer of another of The International Jew. Ford is mentioned in Mein Kampf, something akin to being in the Epstein files today, in some quarters.

A section towards the end of Ms. Woeste’s (thoroughly enjoyable and assiduously researched) book concerns the Jewish lawyer cum activist who rode shotgun for Sapiro throughout the trial. Louis Marshall’s response to Henry Ford’s placatory gestures after the verdict were anticipated by a nation. How would Marshall respond in victory? The section is worth quoting in full:

The more Marshall thought about it, the more he became convinced that the real value of Ford’s apology lay in the impact it would have in places where Jews still lived in fear of their safety. ‘The subject is one of life and death to the millions of Jews abroad’, he told the New York Sun. ‘The International Jew has been translated into the various European languages and has made a deep impression because of Ford’s fabulous wealth and the myth that has become prevalent that he is a leader of human thought and a man of high principles’. The prospect that Ford would separate his industrial leadership from his antisemitic literature gave Marshall ‘more happiness than any action in which I have ever been engaged because I feel that its effect will be far-reaching, especially in Eastern Europe, where anti-Semitism is raging today worse than at any time during this century’.

Now, before I attempt to unpack this epilogue to Sapiro vs. Ford, full declaration:

I am very new to the Jewish Question 2.0, as it exists for us today. In fact, my introduction was The Culture of Critique, by this magazine’s editor. I suspect this was a far more level-headed and objectively informed start than being introduced to the subject by, I don’t know, Andrew Anglin. But there are many on the dissident Right (for want of a better term) who train their gaze on pieces such as this, like Panzer commanders with their binoculars trained on the horizon. Of course, I am not saying save your breath for cooling your porridge. Comment is free (as it says on the Guardian’s website, where it isn’t). I have no interest in the wider spheres of Jewish influence I didn’t mention here, but my reading on the subject is in its infancy. I admire Ms. Woeste’s book as a stand-alone, superbly reconstructed key moment in legal history. I have no idea who she is, outside of her online resumé. Nothing I found makes any reference to her ethnicity. ChatGPT says there “is no evidence she is Jewish”. Woah. Like it’s a crime scene now? If you should look her up, and you were a film director and you wanted to cast the role of a typical Jewish woman in her forties, you would not see any other actors after seeing her. It’s not important, just vaguely amusing. This is a very good book, and I recommend it.

The book left me with two main thoughts on the Jewish Question 2.0, late to the party as I undoubtedly am:

- Sapiro vs. Ford was important both on a legal level and a philosophical level. Libel had always been against an individual. Now that was extrapolated into libelous intent against an entire race, every Jew that exists on the globe, unless their nomadic lifestyle has led them to other worlds of which we do not know. That is an extraordinary and rather crude use of a reductive version of the argument concerning the particular and the universal which began metaphysically with Plato, and raged on with reference to language throughout the Scholastic and Medieval periods. Metaphysically, the fact that any individual thing is both individual and universal (or at least instantiates universality, unless it is unique) is not a problem because its range of effects are confined to the metaphysical. A lot of Plato is not all the harsh politics of the Republic. A lot of Plato is metaphysical chatter in the square, shooting the breeze. But in a twentieth-century court of law, where the potential range of effects include incarceration and pecuniary ruin, to extrapolate from the particular to the universal has somewhat more gravitas behind it. But that it precisely the tactic — call it tribal memory, if you will — which even modern Jewry uses, along with their new pets in the Islamic and African worlds.

- From what I have gathered and gleaned so far, one thing is glaringly obvious; Jewry is not monolithic. As with the Arab world — the Jews’ supposed foes — there is no locus of power for international Jewry. Judaism has no Pope. So, who is at the helm of, as I believe it is known in some quarters, the ZOG? Is it Soros and Co.? the ADL? Israel? BlackRock? Mel Brooks? Whether or not there is a central Jewish cabal, the cabal are not acting for Jews as a people. Unless those Jews murdered across Europe were just taking one for the team. Louis Marshall’s “places where Jews still lived in fear of their safety” in Europe are now Paris, Amsterdam, and Birmingham. Perhaps the whole point of history was to find who gets to be last man standing, capo di tutti capi, top Jew. King of the Jews, maybe.

Finally, there has been another democratization in the tumultuous period between the golden age of the printing press and Ford’s Model-T and today’s online world. Now, you only have to own a cheap mobile phone to get yourself in hot water over anti-Semitism. Ninety-nine years ago, you had to own a newspaper. In terms of personal culpability, we are all newspaper owners now, and just as concerned by Jewish influence as Henry Ford was. William Henry Gallagher, one of Sapiro’s lawyers, makes it clear. Read this paragraph well, because it will show you the legal principle currently operating across Europe with reference to hate speech. The Left disowned moral agency for so long — and still does, if you are Black — but now it is back and, like a Jim Crow saloon, it is for Whites only:

Never lose sight of the fact that Henry Ford stands behind the [Independent], gives his thoughts to it to appear on his Henry Ford Page, and is responsible for the thoughts which appear in it.

Never knew Robert Frost was based. Need to read more of him.

“10 Jews, 12 opinions” (A Jew)

“Cannot make a state because they fight one another” (A Hitler)

“They only unite when they perceive or imagine a collective threat” (A Gentile)

Ford’s concocted apology is a century old, years before WW2 and the Israel-Palestine wars. As musty as Fagin’s garlic-ridden gabardine underpants.

Fascinating review..timely..as millions of Americans reinvestigate The Very Wonderful prescient Henry Ford..a visionary industrialist in his. era…. a Christian and no doubt ..his eyes saw. THE JEWS in all their preternatural inverted

arcane satanic splendor.

Charles lindberg…other pre WW2 names float about the current jew-tyrannized American subconscious..in the cultural ether..Cyclical ..isnt it..as in the very predictable rise and fall of all previous jew-super parasited empires…We see no instant clear analogue in 2026 to the deeply perceptive golden hearted wise Henry Ford.No one can disadmit..or cavil in the hour of The New American Kristallnacht…….however about gay totalitarian jew race supremacist influences.God -not Charles Darwin- help us.! Lord…save us from THE JEWS**

“ the current jew-tyrannized American subconscious.” A most excellent observation concerning the reluctant or not Gentile aquiesence of the last century.

@Mark Gullick

“Sapiro vs. Ford was, perhaps, the first hate-speech trial.”

Henrici and the like were decades earlier.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ernst_Henrici

Very thoughtful piece. Well done.

I envy this guy and the infancy period of his jq epiphanies. Mine was decades ago, but I learn something new daily.

Tread lightly I guess. You cannot unknow what you have labored over knowing.

If only Ford had more of a private militia.