Star Baby and Straw Blasphemy: The Complex Simplicity of the First Christian Story

Varsk’vlavi. That’s a strange word from a strange language. At least, it’s a strange word if your mother-tongue is English and not Georgian, the mother-tongue of Joseph Stalin. As a boy, Stalin himself would have found the word right at the beginning of the New Testament in the Gospel of Matthew:

2:9 და აჰა, ვარსკვლავი, რომელიც მათ აღმოსავლეთში იხილეს, წინ უძღოდა მათ, ვიდრე მივიდოდა და დადგებოდა იმ ადგილზე, სადაც ყრმა იყო. 2:10 ვარსკვლავი რომ დაინახეს, მათ მეტისმეტი სიხარულით გაიხარეს.

2:9 da aha, varsk’vlavi, romelits mat aghmosavletsši ikhiles, ts’in udzghoda mat, vidre mividoda da dadgeboda im adgilze, sadats qrma iqo. 2:10 varsk’vlavi rom dainakhes, mat met’ismet’i sikharulit gaikhares.

2:9 And, lo, the star, which they saw in the east, went before them, till it came and stood over where the young child was. 2:10 When they saw the star, they rejoiced with exceeding great joy.

Yes, varsk’vlavi, ვარსკვლავი, means “star.” It’s a strange word for Anglophones because it’s so long and complex. Where English has one syllable and four letters, Georgian has three syllables and ten letters. But you could say that the word is appropriately complex in Georgian and appropriately simple in English. Stars are complex things after all, giant globes of glowing gas that evolve and explode and still challenge the best brains of the human race to explain and predict their behavior. But on the other hand, stars are simple things too, primal things, bright points of light to the naked eye. Stars are complex in physics and simple in stories, bearing messages that even the youngest children can grasp.

Fleeting but fertile

The Star of Bethlehem bore a simple but stupendous message: Here is the Son of God. Jesus was a star-baby, born humbly on Earth but heralded in the Heavens. His star brought Kings from the East, the Three Wise Men, the Magi whose fleeting appearance in a single Gospel has inspired millennia of Christian art, literature and legend. The star’s appearance is fleeting but fertile too. Only Matthew mentions it and only briefly, but Matthew’s is the first Gospel and the star is central to the first story he tells. Stalin must have read that story as a child, but Stalin would grow up to reject the star-baby of Jesus and follow the straw man of Marx.

The Star of Bethlehem (c. 1887) by Sir Edward Burne-Jones (image from Wikipedia)

The Star of Bethlehem (c. 1887) by Sir Edward Burne-Jones (image from Wikipedia)

Another able and intelligent atheist, the science-fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke (1917–2008), rejected the star-baby too. He replaced it with what you might call a straw star. When I first read Clarke’s short-story “The Star” (1955) as a teenager, I thought it was a clever and cutting swipe at Christianity, a swingeing blow delivered on behalf of science against superstition. When I re-read it today, I see it for what it really is: not a successful swipe against Christian irrationality, but a stroking of atheist vanity. And a soothing of atheist fears. The fears were first those of Arthur C. Clarke himself. He obviously didn’t want Christianity to be true, which is why he created a straw star to swallow the joy-star of Matthew’s Gospel.

Stellar spoiler

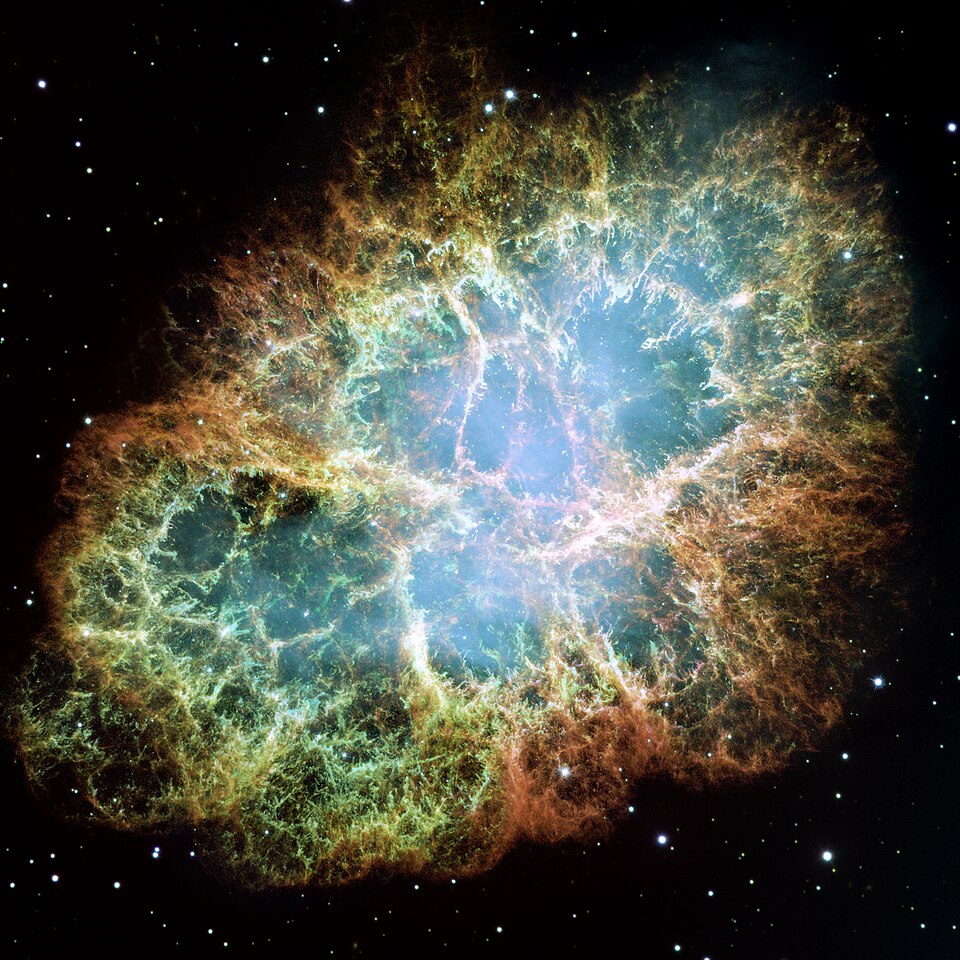

What I describe next will be a spoiler for anyone who hasn’t read his story, but that will be appropriate enough in its way. After all, Clarke intended “The Star” to be a spoiler for Christianity. It’s about a Jesuit priest three thousand light-years from home. The priest is the first-person narrator of “The Star,” an astrophysicist of the far future who’s part of an interstellar mission to the Phoenix Nebula. The Nebula is the remnants of a supernova, the cataclysmic explosion of a once stable star. It turns out that the star had planets and that one of the planets had an alien civilization on it, advanced enough to predict the supernova but not advanced enough to flee its fury.

The Crab Nebula, remnant of a supernova (image from Wikipedia)

The Crab Nebula, remnant of a supernova (image from Wikipedia)

But before the aliens and their home-planet were vaporized by the supernova, they left a memorial of their existence in hope of just such a later mission as the astrophysicist priest is describing. As the priest himself puts it: “A civilization that knew it was about to die had made its last bid for immortality.” The aliens created a vault of records on their star-system’s equivalent of Pluto, a far-out planet that they knew would be the only one to survive the coming cataclysm. Like the other scientists and crew on his star-ship, the priest is deeply moved by what the vault reveals:

If only they had had a little more time! They could travel freely enough between the planets of their own sun, but they had not yet learned to cross the interstellar gulfs, and the nearest solar system was a hundred light-years away. Yet even had they possessed the secret of the Transfinite Drive, no more than a few millions could have been saved. Perhaps it was better thus.

Even if they had not been so disturbingly human as their sculpture shows, we could not have helped admiring them and grieving for their fate. They left thousands of visual records and the machines for projecting them, together with elaborate pictorial instructions from which it will not be difficult to learn their written language. We have examined many of these records, and brought to life for the first time in six thousand years the warmth and beauty of a civilization that in many ways must have been superior to our own. Perhaps they only showed us the best, and one can hardly blame them. But their words were very lovely, and their cities were built with a grace that matches anything of man’s. We have watched them at work and play, and listened to their musical speech sounding across the centuries. One scene is still before my eyes — a group of children on a beach of strange blue sand, playing in the waves as children play on Earth. Curious whiplike trees line the shore, and some very large animal is wading in the shadows yet attracting no attention at all.

And sinking into the sea, still warm and friendly and life-giving, is the sun that will soon turn traitor and obliterate all this innocent happiness. (“The Star,” 1955)

It’s important that the aliens were “disturbingly human” and that they enjoyed “innocent happiness,” because Clarke is setting up the punch-line of the story. The astrophysicist priest studies the rocks of the planet where the vault was delved and is able to calculate the date of the supernova “very exactly.” That’s how he learns when its light must have blazed in the skies of distant Earth and that’s why, as he narrates the story, he’s grappling with a fierce and probably fatal crisis of faith. He now knows the answer to an age-old enigma and the identity of a hallowed entity. Here are the closing lines of his narrative:

There can be no reasonable doubt: the ancient mystery is solved at last. Yet, oh God, there were so many stars you could have used. What was the need to give these people to the fire, that the symbol of their passing might shine above Bethlehem? (“The Star”)

“How clever!” I thought when I read that as a teenager. “How cringe!” I think when I read it now. The supernova of the story is a straw star, a fiction created to fill the mind with a message of disdain for Christianity. And created to mark the mind too: after you read “The Star,” its fiction will cloud the fact of The Star that blazed over Bethlehem. It’s fact for traditionalist Christians, at least, and traditionalist Christians will rightly say that Clarke’s story is blasphemous. I’d say it’s blasphemy on behalf of boy-buggery. Like a disproportionate number of people in science fiction, Arthur C. Clarke was a pedophile and I think the “children … playing in the waves” aren’t there in his blasphemous story just to set up the punch-line. Clarke settled on the tropical island of Sri Lanka in 1956, the year after he published “The Star.” Leftist Wikipedia says that he moved there “to pursue his interest in scuba diving.” I think that the move was also — and more importantly — to pursue his interest in undressed children playing in warm water.

Far, far at sea

Male children, to be specific. But what does Christianity say about pederasty, the “boy-love” that was beloved of the pagan Greeks and philhellene Romans? Christianity says pederasty is wicked and sinful, which is not a message that the pederast Arthur C. Clarke wanted to hear. That’s why, I’d suggest, he created the straw star of his blasphemous story. It’s also why the story won a Hugo Award in 1956. That was one of highest honors in science fiction, because the story was liked by other atheists, other Christophobes and other pedophiles. I liked that star-story myself when I was a teenager, but I don’t like it any more. It’s clever but cheap, designed to fill and fool the mind, not to truly feed it. The star-story in Matthew is different. It does feed the mind. And the imagination. It fed a civilization too, the civilization of Christendom whose star-story was told in Georgian long before it was told in English.

And even longer before it was subverted in English by the pederast atheist Arthur C. Clarke. Nowadays I prefer a Christian star-poem to Clarke’s atheist star-story. It’s a poem that mixes the primality of stars with the primality of an earthly entity that Georgian calls zghwa, ზღვა. That’s an aptly swishing and grumbling monosyllable for what English calls “the sea.” And here is the star-poem, a hymn by a Scottish writer called Jane Cross Simpson (1811-86), who never achieved a fraction of Arthur C. Clarke’s fame and influence but said far more than he did in far fewer words:

Star of peace to wanderers weary,

Bright the beams that smile on me;

Cheer the pilot’s vision dreary,

Far, far at sea.

Star of hope! gleam on the billow;

Bless the soul that sighs for Thee;

Bless the sailor’s lonely pillow,

Far, far at sea.

Star of faith! when winds are mocking

All his toil, he flies to Thee;

Save him on the billows rocking,

Far, far at sea.

Star Divine, O safely guide him;

Bring the wanderer home to Thee;

Sore temptations long have tried him,

Far, far at sea.

“Star of Peace” at Youtube.Youtube.

Stop cherry picking. You take something that some people are touched by and neglect to mention all the other appalling occurrences in both Testaments. I was raised in a society where men build their civilization and culture on Mohammed’s assertion that an angel spoke to him to reveal God’s Holy Word. How many millions (billions) are moved by this miracle and don’t know about or swipe under the flying carpet all the other nonsense and dross? To you, it’s absurd that a whole civilization and culture were founded on this nonsense. Congratulations, now be honest, eschew hypocrisy and myopia, and extend this to all other religions including one which was, in great part, foisted upon your Teutonic ancestors a la ISIS; the Christian variety, obviously.

I’ve been an Atheist for over three decades and I’ve never had any ego like Clarke or Atheist debaters. I’ve never had an ego like Christians, and Muslims, either who view themselves as better.

Coïncidence, I was watching yesterday a video about the Helix nebula, aka the Eye of GOD, or more recently the Eye of Sauron ( because it looks like the Eye above the Sauron’s evil tower in Peter Jackson movie LOTR, it’s a nerd thing and a little silly ).

Atheism is a religion too. A sad idiotic one.

Atheism isn’t a religion. What’s sad and idiotic are religions promising eternal torture for those who won’t believe. What kind of sick and demented minds thinks up such disgusting mentally deranged stories?!

Usually Thailand or somewhere in Burton’s Sodatic Zone. Clarke was a pillar of the British Interplanetary Society and brilliantly debunked the fraud George Adamski. Some of his stories are quite good as are the Stations of the Cross in Westminster Cathedral done by Eric Gill. Still, he wasn’t a “joo”.

Homosexuality, autism and dyslexia seem to be increasing in the west more than a recording accident. Genetic like the lower sperm count, or something in the food or water?

We don’t know for autism but homosexuality becomes widespread when a civilization is on its death bed.

Decadent Rome, Greece : homosexuals proliferate ( though not reproducing ) and become ” fashionable “, women behave like unpaid prostitutes. Je…s and all kind of parasites thrive.