Quantum Dylan: A Double Act, Part 1

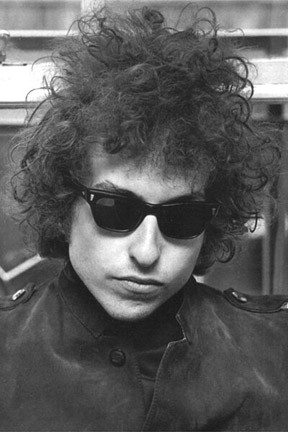

Bob Dylan’s 70th anniversary was celebrated worldwide on May 24th. Hailed as the Shakespeare of his generation, Dylan has sold more than 58 million albums, and written more than 500 songs recorded by more than 2000 artists. Dylan has described himself as “a person who owns the Sixties.” At the same time, he has spent a lifetime “despising the nineteen-sixties — all the while being held up everywhere as its avatar.”[1] To post-1968 generations, the remarkable success of Robert Allen Zimmerman – alias Shabtai Zisel ben Avraham — remains “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” While the success of his precursors Elvis and Sinatra is easily explainable, neither looks, nor voice, nor charisma can explain Dylan’s unique and enduring iconic status. He has been described as diffuse, ugly, even dirty — “His ‘diffuseness’ muddies all the waters whose streams make him up.”[2]

Deconstructing the binary high/low culture divide

In postmodern discourse, the status of ‘high culture’ –- perhaps reaching its historical climax with Clement Greenberg’s 1939 essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” –- has been undermined through exposure of its “inherently White, class-based, West-centric, and gendered elements.”[3] Postmodern discourse tends to break down distinctions between subject and object, consciousness and the unconscious, “oppressor” and “oppressed,” spectacle and spectator, “high” and “low,” etc. The movement of “canon into kitsch, or identification into stylization or exaggeration”[4] can be seen in the art of Andy Warhol — often seen as postmodernism’s chief avatar, “the locus classicus for the deconstruction of ‘mass production,’ and the figure who summarily disrupts every distinction there is, especially the difference between high and low.”[5] Hence, postmodernism seems to express a kind of cultural logic that sociologist Charles Lemert has described as relativistic:

The most important feature of the matrix is that, being relative, it overthrows the rationalist distinctions between the “big” and the “small,” the “greater” and the “lesser,” the “higher” and the “lower,” and so forth. In other words, while the principles of complementarity and indeterminacy rebel against the rationalist epistemological distinction between knowing subject and known object, the relativistic principle overthrows the rationalist ontological perspective that views the natural and human world in hierarchical terms. Relativity radically equalizes all things, persons, events, and facts in reality. All things become platitudinous and, simultaneously, the platitude reigns supreme.[6]

Bob Dylan seems to fit into this picture as a figure heralded by intellectual elites as erasing the distinction between “high” and “low” culture. Rock music has oftentimes (stereotypically) been portrayed as ‘low culture’ — as “anti-intellectual, concerned with the sensual, bodily effects of music rather than with rational thought.”[7] Beneath the surface, however, Dylan’s gravitas — attained from being a ”serious” folk artist — has been important for the ideology of rock as a “higher” cultural form. This ideology (or cultural strategy) has been staged through an alloy of myths, branding and cultural codes.

As Douglas Holt and Douglas Cameron have outlined, the name of the game in cultural innovation is to deliver an innovative cultural expression, consisting of an ideology “brought to life” with the right myths and cultural codes in the aftermath of major historical changes and social disruptions (e.g., the “culture wars” of the 1960s).

As Douglas Holt and Douglas Cameron have outlined, the name of the game in cultural innovation is to deliver an innovative cultural expression, consisting of an ideology “brought to life” with the right myths and cultural codes in the aftermath of major historical changes and social disruptions (e.g., the “culture wars” of the 1960s).

Dylan certainly did that. The messages of Dylan’s music consistently dovetailed with the countercultural views of the wider Jewish community and with the nascent Jewish intellectual elites that came to dominate intellectual discourse in the period following WWII. In the following I will trace the Jewish nexus of Dylan’s reputation.

Electric Blues Jews

Dylan started his career in the early 1960s by writing activist songs with civil rights themes — “Oxford Town” (1963), about the first Black student at the University of Mississippi; “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” (1964), about the death of a Black maid; “When the Ship Comes in,” “Only a Pawn in Their Game,” “The Times They Are a-Changin’”, “Blowin’ in the Wind”, etc. In 1965, however, Dylan stopped writing protest songs and switched from acoustic to electric guitar, merging folk music and rock-and-roll (labeled folk-rock) with a strong Black influence. When he shocked the world with an electric band at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965, half of the fans booed at his fall from grace:

The story of Dylan’s appearance at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival is legendary. In its usual form, Dylan went on stage with an electrified group to the shock and horror of the folk audience, for whom electrified music was anathema. He was booed and, in some versions, Pete Seeger, the elder statesman of the folk revival, looked for an axe to cut the cables to the electric guitars.[8]

It might be described as a Jewish moment. The electrification of the blues had been going on since the late 1930s. What was new was Jews playing electric blues to White audiences. Electric blues was synthesized with White popular music ultimately to produce what became known in the 1970s and 1980s as hard rock. Stratton suggests that some of the shock of Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited was “its electrified, rock backing, the real scandal for the White folk audience, as it was at Newport … and on the subsequent Dylan tour, was its electric blues feel, its Blackness.”[9] Furthermore, Stratton observes that

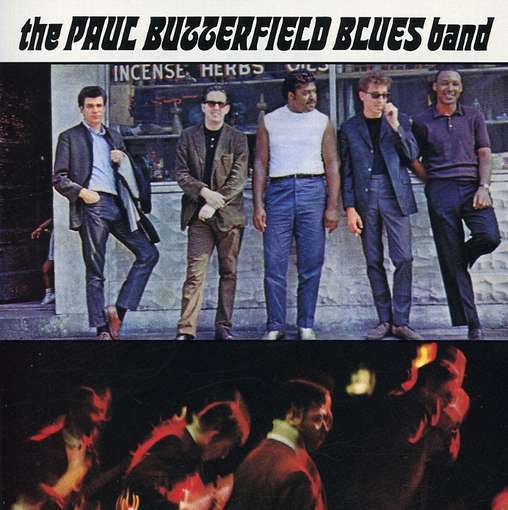

what many people in the folk movement found disturbing about the Paul Butterfield Blues Band’s performance, and that of Dylan, was not so much that they were using electric instruments, but that they were playing versions of African-American music that could not be understood as safely contained in an acoustic past. In other words, there was a racial element to the response. More, there was a racial element to the performances that were predominantly by Jews and African Americans. These two performances at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival publicly aligned Jews with present-day Black, electric blues played in the northern city of Chicago and, therefore, with ‘real’ African Americans. This was what shocked the folk movement the most.[10]

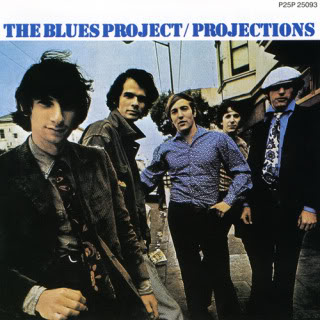

All the members of the New York-based Blues Project were Jewish except for the lead singer Tommy Flanders, who left before the release of the group’s live first album. Stratton notes that the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and the Blues Project were the first predominantly Jewish and African-American groups to play electric blues.

All the members of the New York-based Blues Project were Jewish except for the lead singer Tommy Flanders, who left before the release of the group’s live first album. Stratton notes that the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and the Blues Project were the first predominantly Jewish and African-American groups to play electric blues.

In New York, which was the centre of the folk revival, many of the Jews who moved from the folk revival to electric blues did so by way of an increasing interest in acoustic blues. For example, the folk revival Even Dozen Jug Band was founded in New York in 1963 and made one album for Elektra in 1964. The band had a varied membership, but at its core were Jews: the guitarists Peter Siegel, Steve Katz and Stefan Grossman; the mandolinist David Grisman, and Joshua Rifkin, who went on to a career in classical music.[11]

The two Jews in the Paul Butterfield Blues Band (the group who backed Dylan at Newport) – the guitarist Michael Bloomfield and Al Kooper, who played organ for the first time on the recording of Dylan’s ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ which was released as a single five days before Dylan’s 1965 Newport appearance — were of central importance to the sound of Highway 61 Revisited.

At the two big dress rehearsals for the tour to promote the Highway 61 Revisited album, at the Forest Hills Tennis Stadium in New York and at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles, Dylan’s backing band consisted of three Jews — Robbie Robertson, Harvey Brooks [Goldstein] and Al Kooper.[12]

Stratton points out that the importance of the blues influence on Highway 61 Revisited is often subordinated to the shock for Dylan’s folk revival audience of him “going electric.” But once the blues influence on Highway 61 Revisited is recognized, Dylan can be understood “as a part of the movement of Jewish artists into electric blues”[13] —essentially an electrification of Black culture presented by Jews to White audiences.

The construction of Jews as Whites in the 1960s included a reaffirmation of their Whiteness within the overdetermining American racial structure (“the Black-White dichotomy”). Stratton (p. 87) suggests that their role as mediators being positioned between the two racially polar groups in the United States was crucial to the role Jews were playing in the spread of electric blues into a White audience.

Dylan’s music may be seen as an aspect of the Black-Jewish fusion or commonality of interest that was so critical to promoting the Civil Rights movement – a movement that hosted hostility toward the traditional culture of the West typical of 20th-century Jewish intellectual movements.

Jews have channeled aspects of African-American culture into White culture, most importantly in music the emphasis on emotional expression and the practices through which that emotional expression is given form. More recently, Jewish musicians have invoked elements of Yiddishkeit, most importantly klezmer, to assert a ‘Jewish’ difference from Whiteness and a Jewish place in the American multiculture.[14]

An archaeology of the causalities involved would have to include Jewish middle-class alienation from White culture — an aspect of the culture of critique. Starting in the folk revival’s celebration of acoustic blues, by the mid-1960s, and epitomized in Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited, the electric blues movement, pioneered disproportionally by Jews, expressed increasing disillusionment with White middle-class suburban society by promoting a constructed image of a marginalized working-class African-American culture.[15]

Most of the characters involved were Jews coming from middle-class backgrounds: Stefan Grossman, Danny Kalb, Roy Blumenfeld (the drummer in the Blues Project whose father was an orthopaedic surgeon), Andy Kulberg, Al Kooper, Michael Bloomfield (who detested the White middle-class, conformist suburbia of his childhood), among others.[16] The bulk of the group that backed Dylan at Newport came from the Chicago-based electric blues group Paul Butterfield Blues Band — one of the first integrated American popular music groups. Stratton retells a story about how Bloomfield joined Butterfield’s group:

Paul Rothchild, a producer with Elektra, was taken by Butterfield to see Bloomfield’s group play. Butterfield had asked Bloomfield a number of times if he would join his group, but Bloomfield had always refused. Rothchild tried: “Michael comes and sits down at our table. We shake hands. We then do a half hour intense intellectual Jew at each other. He found a kindred soul, I found a kindred soul.” Bloomfield agreed to join Butterfield’s group. Rothchild first recorded the group in December 1964, and produced their first release the following year.[17]

Michael Billig (Rock’n’ Roll Jews), among others, has pointed out that a crucial number of influential songwriters and behind-the-scenes operators were Jews. Dick Weissman observes that “it was the infrastructure of the folk music business that was largely dominated by Jews.”[18] Stratton confirms that

all three major folk-oriented record labels, Elektra, Vanguard and Folkways, were owned by Jews, and most of the important managers — including Harold Lewenthal, who managed Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, the Weavers, and Judy Collins among others; Manny Greenhill, who managed Joan Baez among others; and Albert Grossman — were Jewish. Grossman … at different times managed Peter, Paul and Mary, Gordon Lightfoot, Dylan, the Band, the Electric Flag, and Janis Joplin among others. He was born and grew up in Chicago and, before moving to New York, opened the first folk club there in 1956, the Gate of Horn, where Bloomfield used to go before he graduated to the black blues clubs. Gillian Mitchell, in The North American Folk Music Revival, argues that, ‘Many of the most significant and pivotal figures in the American folk revival were Jewish’, and goes on to explain that this included both performers and organizational figures. Ned Polsky, in his ethnography of the Greenwich Village beat scene in 1960, notes more generally that, “The Village devotees of ethnic music are historically minded, scholarly, middle-class youths, mostly Jewish.’ Clearly, Jews were central to the folk revival.[19]

This list could be extended. Jerry Schoenbaum, for example, was the Jewish president of Verve Folkways, the label to which the Blues Project were signed. Chess Records — for whom most of the well-known Chicago electric blues artists recorded — was run by Jewish brothers Leonard and Phil Chess, born Lejzor and Fiszel Czyz, who had migrated from Poland in 1928.[20]

Mainstream historiography reports that post-WWII USA, from the late 1940s, became “positively philo-Semitic in its embrace of Jewish culture.”[21] The war itself and the early Cold War “helped to speed the alchemy by which Hebrews became Caucasian.”[22] At the same time, there was a “disproportionately Jewish involvement” in the counterculture during the 1960s — with Jews playing a key role in the folk revival movement of the 1950s and 1960s.[23]

Andrea Levine suggests that the Jewish-American preoccupation with counterculture, Black culture, and the electric blues, in the 1950s and early 1960s, was motivated by an effort “to appropriate a powerful phallic ‘Blackness’ for the White hipster [that] functions in part to mask the presence of another racial body: the Jewish victim of the Nazi Holocaust.”[24] Levine argues that “The White Negro’s” fetishization of an aggressive African-American response to a history of persecution is in part “an effort to obscure the image of the cowed, impotent Jew, going meekly to the gas chamber”.[25]

The blues revival has been judged as a reaction against White, middle-class society, a stylized revolt against bourgeois values: “Rejecting conformity to middle-class values, blues revivalists embraced the music of people who seemed unbound by the conventions of work, family, sexual propriety, worship, and so forth.”[26] Stratton cites Mark Polizzotti, describing how a photo of Dylan and Michael Bloomfield at Newport “catches them grinning at each other in amazed delight at the sounds they’re producing: two Jewish cats making the music come to life, reviving the blues, a faith more real to them than the religion of their fathers.”[27]

End of Part 1

References

Dettmar, Kevin J. H. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Bob Dylan. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009

Lemert, Charles. Durkheim’s Ghosts: Cultural Logics and Social Things. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006

Meisel, Perry. Blackwell Manifestos: Myth of Popular Culture: From Dante to Dylan. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009

Murphy, Peter & Eduardo De La Fuente (eds.). Philosophical and Cultural Theories of Music. Vol. 8. Leiden & Boston: Brill, 2010

Stratton, Jon. Jews, Race and Popular Music. Farnham & Burlington: Ashgate, 2009

[1] Peter Murphy, “Bob Dylan Ain’t Talking: One Man’s Vast Comic Adventure in American Music, Dramaturgy, and Mysticism”, in Murphy & De La Fuente 2010, 49 — 50

[2] Meisel 2009, 166

[3] Dettmar, Kevin J. H. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Bob Dylan. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009, 107

[4] Meisel 2009, 71

[5] Meisel 2009, 71

[6] Lemert 2006, 74

[7] Dettmar 2009, 105

[8] Stratton 2009, 83

[9] Stratton 2009, 86, 89

[10] Stratton 2009, 84

[11] Stratton 2009, 85

[12] Stratton 2009, 83

[13] Stratton 2009, 85

[14] Stratton 2009, 198

[15] Stratton 2009, 93

[16] Stratton 2009, 90 — 92

[17] Stratton 2009, 82 — 83

[18] in Stratton 2009, 97

[19] Stratton 2009, 97

[20] Stratton 2009, 87, 92

[21] Karen Brodkin cited in Stratton 2009, 109

[22] Matthew Frye Jacobson cited in Stratton 2009, 109

[23] Stratton 2009, 79 — 80

[24] cited in Stratton 2009, 95

[25] in Stratton 2009, 96

[26] Jeff Titon cited in Stratton 2009, 93

[27] in Stratton 2009, 99

Comments are closed.