“Unstoppable”: Why I Write

Few readers have likely noticed, but my contributions to this site have fallen dramatically this year. The reason is simple: I’ve been convinced by the likes of Alex Kurtagic, Harold Covington et al. that merely tap-tap-tapping on computer keys accomplishes little. Worse, I know I’m guilty of what they both disparage: writing negatively about our situation. On top of that, I have nowhere near the skill or imagination needed to construct a useful new “myth” for our people a la the peerless Michael O’Meara. Result: I’ve stopped writing.

Still, I do continue to teach students how to read a film, but of course I do not do so openly from a White Nationalist position, nor did I mention the role of Jews as a hostile elite. I also write academically on film, so it’s not like I have writer’s block.

In fact, for some years now, I’ve been focused on the films of two chosen Black actors, Morgan Freeman and Denzel Washington. I’ve argued that the anti-White structure (erected by Jews) in Hollywood has demanded the creation of model Black men to “teach” the population that such characters are the norm in our new multicultural society.

A while back, writing in The Occidental Quarterly, I discussed in Understanding Hollywood: Racial Role Reversals the concept of these “numinous Negroes.” The term describes not just leaders and heroes. Rather, such Blacks are also paragons of wisdom — moral and spiritual exemplars, and Morgan Freeman is Hollywood’s favorite actor for numinous Negro roles. Ever since his breakthrough as chauffeur Hoke Colburn in Driving Miss Daisy (1989), Freeman has consistently been cast as a man of rare intelligence, sensitivity, and moral grounding, usually paired with younger Whites who admire him for his superior wisdom and seek his guidance.

Denzel Washington has been cast in similar roles for someone almost two decades younger. The consistency and longevity of these “reel” characters convince me that it is all part of a conscious propaganda effort at further knocking down White men, using Blacks as proxies. In that sense, it’s an old story.

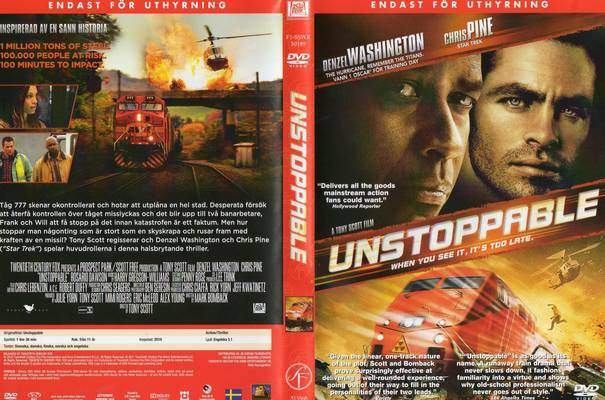

My TOQ Hollywood essay appeared in the Summer 2009 issue, preceding two new Washington films by a year. In 2010 his film Book of Eli appeared, followed by one I was really looking forward to, Unstoppable. (See movie trailer here.)

When I was finally able to watch Unstoppable on DVD earlier this year, I was stunned at how perfectly it fit my previous discussions on numinous Negro films. While this time it lacked the normal Denzel Washington lessons about the evils of ongoing White racism, it did have that Washington standard: the replacement of White power with Black power. And isn’t power what it’s all about when it comes to the multicultural project?

I used this film in three different classes this semester, so it is still very fresh in my mind. And each time I watch these carefully choreographed scenes, I’m more and more impressed by the insidious craft that went into this propaganda picture.

Finally, I’m reading to write about Unstoppable because last week I was fortunate enough to read Trevor Lynch’s short essay Why I Write on Greg Johnson’s Counter-Currents site. It was more than enough to convince me to get this review done.

Lynch is a concise writer, asking, “Why do I write movie and television reviews from a White Nationalist perspective? It’s complicated.”

By way of explanation, he writes:

By integrating so many art forms, film can communicate more, and more deeply, to more people, than any single art form. (The same is true of television. The screen is just smaller.) . . .

Second, I write because movies are a force. They are the greatest tool ever invented for shaping people’s ideas and imaginations. In the right hands, they can be a force for good. In the wrong hands, they are a force for evil. Unfortunately, the film industry in the United States and Europe is overwhelmingly controlled by an alien and hostile people, the Jews.

Jews use movies as a tool to promote ideas and values that are destructive of my race and civilization: race-mixing and multiculturalism, White guilt and self-hatred, feminism and emasculation, the valorization of Jews and non-Whites, etc. Film reviews are one way that I can fight back.

He further explains that because “the film, television, and advertising industries comprise a vast number of highly intelligent, creative individuals with many billions of dollars of capital at their disposal, with which they create a 24/7 matrix of genocidal anti-White propaganda,” we White Nationalists cannot compete.

Fortunately, there is one obvious way to combat this: “We can teach our people to see through the propaganda.” And that sums up my own motive for writing so much about film.

Lynch shows that “we can negate the propaganda churned out by legions of enemies with billions in capital. This is asymmetrical cultural warfare at its best. Our power is limited only by our readership.”

By illustrating the general principles of anti-White propaganda, we can teach readers how to decode propaganda in general. This, Lynch writes, has two profound effects:

- Whenever a brainwashed person is exposed to propaganda, it reinforces the establishment message. However, when we teach people to see through propaganda, then each new exposure reinforces our message instead. Imagine a young man who stumbles across one of my reviews because he is reading up on a movie he wants to see. He might like my interpretation or hate it. He might even reject my claims about the propaganda content of the film. But if he is bright, he will carry away a template for viewing other films, and he will begin to see the same patterns again and again. Gradually, the establishment’s power over his mind will fade, and the nagging little voice of Trevor Lynch will get louder and louder.

- When people learn to see through anti-White propaganda, they are often shocked by its omnipresence. It is one thing to see propaganda here and there. It is another thing to see it everywhere. Even I am still shocked when I visit friends who have cable. The anti-White message is everywhere: in every cooking program, every cute animal show, every house makeover program. You can’t escape it, and that’s no accident. When you see the omnipresence of the lie, you have a concrete experience of the system’s totalitarian nature and genocidal intent. [emphasis added]

Now let’s see how this is done in Unstoppable.

This is a modern story about the hardscrabble world of railroading in central Pennsylvania, whose coal-filled mountains originally prompted the birth of rail in America. Home to such illustrious railroads as the Lehigh Valley, the Erie, the Lackawanna, and most of all the Pennsy (Pennsylvania Railroad), this region was a world of steam, iron, steel, and hard men. Hard White men.

You can forget about all the talk in today’s modern classrooms of “White male privilege,” for the vast majority of this mixed ethnicity of White men worked long, hard hours in dangerous conditions. My own great-grandfather worked six-day weeks, sometimes twelve hours a day in honest toil. That is how life was then.

Unstoppable, of course, is a modern Hollywood suspense thriller, so it has no need for the White past. Unlike, say, Crimson Tide (1995), in which Washington’s character competes for control of a nuclear ballistic missile submarine with a White captain played by Gene Hackman, Unstoppable is more in the mode of the buddy film, which in recent multicultural years has most often been shown as the Black-White buddy cop film. (Think 48 Hrs., the Lethal Weapon series, Beverly Hills Cop, etc.)

On second thought, perhaps the buddy film is the wrong category. Because Washington’s Frank Barnes plays mentor to young White male Will Colson (Chris Pine), we should more properly call it a “numinous Black mentor” film. Morgan Freeman has more typically been assigned this role in film, as The Shawshank Redemption (with Tim Robbins), Se7en (Brad Pitt), The Sum of All Fears (Ben Affleck) and two Batman films attest. His 2007 film with Jack Nicholson, The Bucket List, likely fits this genre as well.

Unstoppable sets up this Black mentor-White student relationship early on, as Barnes stresses to Colson that he’s been working on the railroad for twenty-eight years, versus a few months for the White rookie. Throughout the film, Barnes commands — and teaches.

In practice, this kind of Black mentor film is probably very useful in creating subtle assumptions in the minds of the audience about the “natural” role of Black men — intelligent, experienced, caring . . . and superior. (For example, while Colson’s domestic situation is a shambles, Barnes’s family life is the picture of domestic bliss.)

Still, as Barnes and Colson throw themselves into the task of stopping a runaway freight train, they equally show bravery and determination. My students correctly noted that the message here is that Black and White can work productively and peacefully together—under the wise leadership of a Black man.

One annoying tidbit — because it is so counterfactual yet so common in Hollywood fare — is that Barnes is a math whiz, able to calculate in his head railcar lengths and distances on the track. Young Colson is merely puzzled by all that mental wattage.

Something missing from this film, however, which is really a Denzel Washington staple, is an embedded lecture about White racism. I would estimate that upward of seventy-five percent of his films feature this theme, often with the subtlety of an anvil being dropped on your head. In Unstoppable, however, it is a post-racism world, a world that works.

Saying it is post-racism, however, is not to say race plays no role, for in fact there are ongoing secondary stories where race is the point — and White men come out on the losing end.

Ethan Suplee as Dewey the engineer

First, early in the film we see Hollywood’s go-to moronic White fat man, Ethan Suplee, shown as dim-witted, lazy engineer “Dewey.” Assigned to move a freight train in the yard, he hobbles aboard and gets it moving. When he notices that a switch ahead is out of position, he sets the safety brake and prepares to get out and move the switch himself. Back on the ground his partner discourages him, but Dewey insists.

Once out of the cab, the engine kicks into full throttle on its own accord, and Dewey is faced with the task of chasing it down, re-boarding, and taking back control of the empty train. Because he’s so fat and out of shape, he can barely keep up with the slow-moving train and falls face first into the stone ballast alongside the train. Now they have a “coaster” on their hands.

More needs to be said about obese actor Ethan Suplee. Hollywood seems to love using this blob to create the image of the stupid fat White Everyman. For instance, from 2005-2009 he played Randall “Randy” Dew Hickey, younger brother to Earl on the hit TV series My Name Is Earl. Wiki says that Randy “is thought to be very dimwitted and simple, bordering on mild mental retardation.”

A far earlier incarnation of the dumb fat man came in the powerful 1998 neo-Nazi film American History X. Here Suplee was cast not only as a fat White imbecile, but as a fat White skinhead neo-Nazi imbecile with tattoos and an unquenchable hatred for non-Whites. Not a very appealing character.

Two years later he appeared with Denzel Washington in one of the most manipulative anti-White films I have ever seen, Remember the Titans. Directed by Boaz Yakin and produced by Jerry Bruckheimer, both Jews, this film is a straightforward replacement film. That is, the main White characters are replaced by Blacks and all turns out for the better. The White coach is replaced by Washington’s character (and learns to be happy about it), the White quarterback Gary is replaced (and is later shown in a Christ-like pose symbolically celebrating this new team), and another White player even asks the coach to replace him with a Black player in the middle of the big game.

How Suplee and his bulk are used in Titans is instructive. The script repeatedly shows him as overtly stupid and always contrasts that to Black smarts. For instance, when they go to football camp in Gettysburg, PA (Yes, this is used to ruminate on the racism surrounding the Civil War. And yes, they went to camp in school buses, which is used to educate us on the necessity of 1970’s busing) Suplee the fat lineman is asked by Washington’s coach character what his future plans are. College? No, the lineman answers, “I’m no brainiac like the Rev.” Jerry “Rev” Harris, we see, is Black.

In any case, the Black coach offers to tutor the fat White lineman. Later, there is even a scene where the lineman himself blurts out that he’s “nothing but no-good White trash.” Not to worry, as “Rev” Harris the Black genius will also tutor him. Are we starting to get the point?

Finally, two years later, Suplee again appeared with Washington, this time in a minor role as a stupid security guard at a hospital in the tear jerker (for Blacks as victims) John Q. Thus, including Unstoppable, Suplee has been thrice used as a moronic fat White man, all the better to accentuate Denzel Washington’s tall muscular figure and scripted brain power.

The most pronounced propaganda message in Unstoppable, however, comes with the character of Connie Hooper (Rosario Dawson), who I thought was Black until I looked her up in Wikipedia. In Unstoppable she improbably plays a yardmaster and predictably berates Dewey and his partner when the train “gets away” from them. “It’s a train, Dewey, not a chipmunk.”

The real scripted message, though, comes with this sassy New York City girl’s confrontation with her supervisor, Oscar Galvin, an overweight, overbearing White guy. Repeatedly, his plans to stop the train fail and nearly lead to disaster, while Hooper’s plans would have worked.

Further blaming White men, we see a scene at a railroad crossing in a small Pennsylvania town. The policeman competently directing traffic is Black. The man driving a dump truck that is about to hit a horse trailer next to the tracks is, none to my surprise, White. He was fiddling with the radio trying to get a better country and western station when his truck rams the horse trailer, which of course ends up on the track and gets demolished by the runaway train.

One final anti-White male comment comes when a decision must be made at railroad headquarters about what to do with the rogue train. In the boardroom the camera pans a sea of White male faces, save for one Black sitting at the corner. These men clearly value dollars over lives, as the dialogue shows, and the camera duly zooms in on White (non-Jewish) men, including a foursome out enjoying an afternoon round of golf while Armageddon awaits.

Despite this, the film is not consistently anti-White male. After all, Will Colson, the young conductor, is White. In addition, a knowledgeable inspector who happens to be at the railroad yard is White, as is Ned Oldham, a welder who performs heroically. Even more heroic are two would-be rescuers, one of whom gives his life. He is Judd Stewart and drives two engines that are meant to couple to the runaway train and slowly brake it. The other is a young Marine who attempts to drop from a helicopter to stop the train and is seriously injured in his attempt.

Thus, the movie shows heroics from both Black and White. The point, however, is that only Whites are associated with bad things, as noted above. In other words, if it’s bad, it’s White. This may seem to be an insignificant point, but when viewed in the larger context of the multicultural project to dispossess White men, it becomes important.

Finally, as the credits role at the end of the film, loud music sung by Black women covers the resolution of each character’s future. Barnes and Colson do well, as does the Hispanic woman Connie who, the subtitle tells us, has replaced the White Oscar Galvin as VP of Train Operations. Finally, we see Suplee’s fat character looking up from the gravel: “Dewey is currently working in the fast food industry.”

Unstoppable is an easy film to decode. Consider sharing this article with friends or family who realize that something is going on but are not yet race-wise about it. The movie is entertaining, but can also be used as a training tool — but not as Hollywood intended.

Comments are closed.