The Southern Point: Bardic Dynamic, Pt. 2

“The study of literature is hero-worship. It is a refinement, or, if you will, a perversion of that primitive religion.”

Ezra Pound, from The Spirit of Romance

The Bardic Dynamic focuses on the magnetic relationship between a speaker and an audience and the communication of a fundamental series of ideas. Traditional examples of this can be found in the great epic poems of Western Civilization. Ezra Pound believed that before about 1750 or so, the quintessence of Western man could only be found in poetry (Pound, 31). The context of these older texts is often an address made by one who remembers to those who may have forgotten. The bard or poet was the “keeper of memories.” This is a very different conception than that which has developed in contemporary times with the hip-hop rapper and his thousand miles a minute ebonicspeak, backed with heavy bass beats or the coffee-house Ginsberg wanna-be railing against, well, against G.I. Joe Whitey, of course. Who else?

The fashion in which the memories were catalogued provides a glimpse of an oral tradition that outlined communal identity and put forth the ideal of the hero. This “live” speaking has been fundamental to group development in all periods. Attention to the epic form also involves the recognition of a generally accepted scale of values or a web of meanings based upon the recollected experiences of a specific kinfolk. This web of meanings was communicated through a form of charismatic leadership, resting upon the power of a singular, ubiquitous voice that could speak well. The subject matter often involved little more than recounting the key scenes (cinematic moments) from the day’s battles in a compelling manner, in order to facilitate a return into the field the following morning. As time went on, these meditations became more internal and psychological up until the absolute subjectivity of modern poetry and the complete derailment from the connection with the community. This is the error we would try to mend today, thereby reestablishing a more effective continuity between the past and the present as well as between the individual and the group.

Certain extraordinary heroic cycles and turns of phrases gained in popularity through their repetitive retelling, until they reached a grandiose magnitude and became literally, the songs of a people. These songs became reference points and buoys during times of hardship. They represented bulwarks for the spirit as well as catalysts for future heroic action, measuring sticks for those who wanted to test themselves against the greatest examples available. The Odyssey, the Iliad, the Aeneid, the Bible, Beowulf, The Eddas, The Icelandic Sagas, The Divine Comedy, El Cid, The Song of Roland, and L’Morte D’Arthur are all examples in the Western tradition of the relationship between a persuasive speaker and a people at various key turning points in our civilization’s history.

The survival of these vivid heroic testaments is proof of the evolutionary value of the Bardic Dynamic. Science didn’t figure this out. It unraveled some important mysteries, no doubt. But it also endorsed an unfortunate spiritual shriveling that has inhibited the development of the older and more robust personalities that our forebears displayed so boldly. Fortunately, the seed form of these personalities has been partially been preserved in our poetry and literature in exactly the same way that amber perfectly fossilizes ancient life forms.

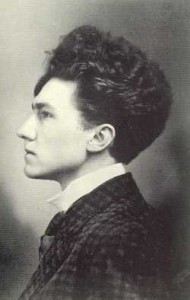

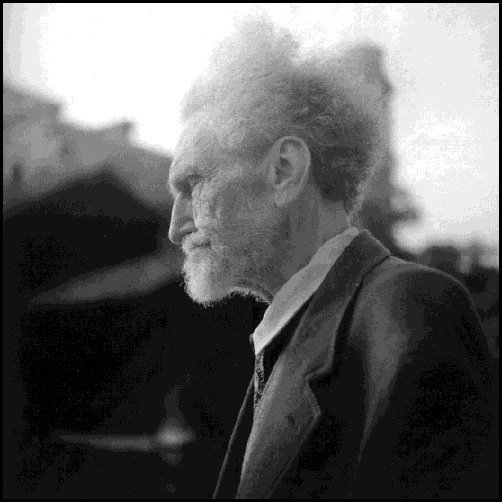

Although the United States is still young in the grand scheme of human events and fast heading off a cliff, several American poets have periodically attempted to enunciate an American epic that put forth a heroic vision of our historical experience. These efforts provide us with a starting point of a stand, if nothing else. Realistic beginnings have been made against a backdrop of frontier development and subsequent worldly engagement during the 20th century. According to Jeffrey Walker in his book Bardic Ethos and the American Epic Poem: Whitman, Pound, Crane, Williams, Olson:

The poets had taken up the Whitmanesque project for a “great psalm of the republic” that would cultivate a national ethos — or the vital will of what they imagined to be a latent aristocracy, a “true America,” the necessary catalyst for creating a splendid, even world-redeeming national civilization. The ethical cultivation of this vital, aristocratic will required, the modernists believed, the communication of historical intelligence, the moral gist arising from a mythic history that “told the tale” of struggle between the agents of creative will and the anti-vital, torpid, and degenerative counterforces in the common mind. But the bardic poem would not tell that tale, at least not directly. Instead, it would enact the discovery of a sublime historical intelligence and would seek through the dramatic presentation of a bardic voice to involve the reader in that process. (81)

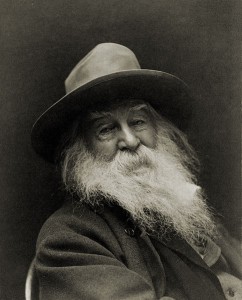

In 1909, when Pound was discovering his Whitmanesque identity, he was also carrying on a correspondence with his mother about … the nature of epic and the role of the American poet. Pound’s examples, in that exchange, were Dante and Whitman, and his definition of epic was “the speech of a nation through the mouth of one man.” Obviously, the definition is debatable, as far as a theory of epic goes, but it is highly revealing as a description of the American bardic voice. (84)

Like Whitman, then, Pound would constitute himself as the elect of the elect, the voodoo aristocrat or shaman-king, and

would align himself with ancient powers and ancestral spirits. Their voices, as a nation or a tribe, would emerge from his own mouth. Through the abysmic bard [i.e., he who seeks deep into the abyss of the collective unconscious], Whitman said, many long-dumb voices speak. And, like Whitman, the bardic Pound would speak in the interest of cultural, political, and economic revolution as the decayed aristocracies of the past gave way to the new/old order. The American bard would speak once more with a terrible negative voice, denouncing infidelism where he found it and announcing or promoting a countervision of right conduct and right society. He would promote the ethical will of an ebullient, freely creative “eugenic paganism” — the modern version of Whitman’s “savage virtue.” He would promote also a revitalized society providing that will with scope for its fullest expression. (85)

Pound sought to resurrect an American artifex, a term that connotes something akin to the “Renaissance Man” of modern parlance, a sincere and versatile genius capable of harnessing the diverse components of a civilization together. Odysseus was a classic example of this type from ancient times, with his crafty and brilliant leadership skills. Pound believed that a man like Thomas Jefferson was the epitome of the artifex in North America. Jefferson had an inventive and creative mind. He was more than just an administrator. He was polumetis, a multifaceted statesman who was also an architect and an artist. In Jefferson and/or Mussolini, Pound suggests that Jefferson was the de facto ruler of the United States during the entire generation ensuing Washington’s initial leadership.

Obviously, that is debatable but the illustration is useful because it suggests that the magnetic power of charismatic leadership might extend beyond the parameters of authorized governing powers (e.g.,. the four-year presidential term). Influence is ultimately related not to positions held but rather to the power of presence. Pound tried to establish a vivid similarity between the type of leadership that he perceived in Benito Mussolini and his conception of Jefferson’s example. Sidestepping the obvious dissimilarities, he encouraged his audience to view the two as talented political artists and men who were in touch with the “root-and-branch” elements of their respective folk communities.

The artist has been at peace with his oppressors long enough. He has dabbled in democracy and he is now done with that folly. We turn back, we artists, to the powers of the air, to the djinns who were our allies aforetime, to the spirits of our ancestors…The aristocracy of entail and of title is decayed, the aristocracy of commerce is decaying, the aristocracy of the arts is ready again for its service…and we who are the heirs of the witch-doctor and the voodoo, we artists who have been so long the despised are about to take over control.

-Ezra Pound, 1914 (Walker, 84)

Yet Pound ultimately failed in this project. This was partly because he could not connect his “terrible negative voice” to a national audience. If anything, his more polished poetry is aimed at a small circle of fellow poets, revolutionaries, and sacerdotal literati (priestly men of letters outside of the Church). In my opinion, his masterwork, The Cantos, is impossibly obscure, fragmented, and esoteric. Though that doesn’t necessarily nullify its value, he himself was divided over its ultimate utility for posterity. For those with a deep multilingual knowledge of various cultural literary episodes arranged in a bizarre labyrinth of cinematic moments, it may provide considerable insight. It is still highly regarded in some circles. He even won a Bollingen prize for it, while he was languishing in a mental institution because of his sympathies in World War II.

Pound spent a large amount of his professional life as an expatriate in Europe, extrapolated from that “common mind” in the heartland of America which desperately needed leadership, especially from someone attempting to create a “great psalm of the republic.” While there is something to be said for distancing art from the bourgeois mentality, it is also possible to become too estranged from one’s people to maintain any sort of decipherable communication. And despite his genuine attempts at preventing American intervention in Europe during World War II, he engaged in the dubious strategy of aligning himself with the Italian fascist regime after the US had decided to go to war and was ultimately labeled a traitor who could only save himself by declaring his insanity. This has effectively cut him off from younger generations who have not been able to resonate with his political choices.

Nevertheless, it is still important to note that Pound is considered to be the preeminent poet of the Modernist movement in the 20th century. His definition of Modernism is summed up in his encouragement to all artists to “Make it new!” His threefold formula for contemporary poetry from his essay “The Art of Poetry” still holds water:

1) Direct treatment of the ‘thing’ whether subjective or objective

2) To use absolutely no word that does not contribute to the presentation

3) As regarding rhythm, to compose in the sequence of the musical phrase, not in sequence of a metronome (Pound, 3).

This “newness” was not aimed at forgetting or destroying the past but rather towards bringing it into the present more effectively. In a review of The H.D. Book by Robert Duncan, Greer Mansfield suggested that,

even though Pound, H.D., and their fellow Modernists were revolting against rhetorically cluttered and metrically anemic “late Romantic” verse, restoring meaning and vigor to poetry by cutting words and drawing with clear and precise lines, they were also conscious inheritors (and refiners) of pre-Raphaelite and Romantic poetry. Pound and H.D. both wrote poems filled with romantic pre-Raphaelite imagery of flowers and trees, longhaired maidens and chivalrous knights. It was imbued with what Pound called ‘the spirit of romance.’

T.S. Eliot dedicated The Wasteland to him, as Pound had been Eliot’s chief editor. He was a close friend of W.B. Yeats. Pound encountered almost every luminous aesthete of his day and virtually all of them were impressed by his erudition and fluidic intelligence. He advanced many of their careers. He also made many important social comments, especially regarding usury, outside of his poetry, that serve to verify contemporary reactions against the materialism which has fully succeeded in infiltrating and corrupting our intelligentsia today.

Ezra Pound was born in the Hailey, a town in the Idaho frontier territory in 1885. His fiery radio rants in Italy during the War had a folksy, populist tone. Even from the pinnacle of the avant-garde of Modernism, he was unable to fully shed his uncouth and raw American roots which couldn’t help but to ‘tell it l’ak it is.’ Pound explained his understanding of the fascist movement as a struggle to embrace quality over quantity. He said,

The fascist revolution was FOR the preservation of certain liberties and FOR the maintenance of a certain level of culture, certain standards of living, it was NOT a refusal to come down to a level of riches or poverty, but a refusal to surrender certain immaterial prerogatives, a refusal to surrender a great slice of the cultural heritage. (Jeff and/or Muss, Chapter XXXII)

Unsurprisingly, establishment critic Jeffrey Walker is convinced neither by Pound’s example nor his “take” on fascism. He suggests that Pound’s voice is irrelevant because he said unattractive things and he failed to convince a larger group that he was right. His failure, according to Walker, is connected to a charismatic and moral shortcoming. Like many others, he takes Pound to task for his anti-Semitism and instead offers up (in a strange detour if one does not already know how the cultural terrain is mapped) the good Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. (!) as an alternatively successful sacerdotal literatus, who succeeded in altering the national will, where Pound and his fellow elites had failed. (238)

However, Walker winds up with this interesting speculation:

Let us suppose, for a moment, that the poets are right. Their argument is not, after all, wholly without sources of appeal. The mythic history with which they work, not to mention the elemental antithesis of Jefferson and Hamilton (or a sort of populist republicanism versus Federalism, big government, and the banks) is a version of a mainstream political mythology that is still viable today. The poets also have available to them a potent, commonplace notion of personal liberty, as well as a belief in the moral responsibilities of legislators and men of affairs. It is conceivable then, that the literatus could use his mythic history to convince us that the rights of man – conceived in terms of personal liberty within a stable and beautiful social order – could best be served by an enlightened authoritarianism, or by a privileged aristocratic intelligentsia that looks to the artist for its ethical guidance and promotes the enterprise of factive, inventive individuals. It may be possible to demonstrate that the demo-liberal, egalitarian ideals of “anonymous government” or “mobocracy” really are absurdities (as William James suggested) and inconsistent with the lessons of history. It may be true, in short, that the poets preferred authoritarian polity is really most consistent with the high national ambition to create a splendid, world-redeeming civilization equal to, or better than, the greatest civilizations of the past. If the poets could really convince us of the justice and responsibility of their preference, we would unquestionably be driven to a hard choice, one involving a profound redefinition of the national ethos. (239)

Rather than redefining the national ethos, I would assert that the process would be closer to a reminding of something that is already there, namely, the historical and literary experience of the Rest of the West.

Despite his genuflection before gods of political correctness, I do like that Walker entertained the idea that public speakers and statesmen could attain to the sacerdotal literatus status. It offers a novel perspective on energetic populism as a precursor to the higher concept of a leader as prophetic seer and of a bard as a lot more than a court jester.

The Bardic Dynamic is still an unfinished and open-ended project in the United States. I believe that its further evolution will involve the development and emergence of distinctive new voices from a populist soil which will then “blow the top off” through some form of comprehensive nullification at a local yet global level. It will probably look, on the surface, very much like the populism of earlier generations with one primary qualification: conscious White advocacy. If we speak for White people, then we must speak as White people. We’ve never had to qualify it like that before because we assumed either that racial consciousness was a given or that we had to be vague in order to sidestep modern politically correct sensibilities. No longer. Now, it must be taken and secured with a well-tempered righteousness that then assumes a mantle and populist rhetoric that is already in place. Other people do not do things like we do. We cannot speak for them. Nor should we try.

In order to be useful, therefore, this historical intelligence must fundamentally reassert the moral claim of the traditional White people and culture of the United States. The White folk built this country. It is ours, if we act. As Joel Chandler Harris once mused, “I think…that no novel or story can be genuinely American, unless it deals with the common people, that is, the country people (Collier 182).” That goes for the epic, too.

The Bardic Dynamic could be focused on facilitating charismatic leadership by promoting confidence in the traditional people and culture of the West as a substitute for the guilt and groveling that is currently poured in by the MSM. It may also be useful in reestablishing the conduit between a leader and a people. It looks to the communicative popular arts and is trained on heroic endeavor and example as recorded by our writers, storytellers, artists and public speakers, rather than scholarly abstractions that flee to the citadel of a scholastic environment, a Parisian salon, or a downtown high rise. It seeks a soapbox and a town square, or a good bonfire. Most of all, it seeks fellows of a like mind.

You ask me what my program is. Here it is, you hicks. And don’t you forget it. Crucify ‘em! Crucify Joe Harrison. Crucify anybody who stands in your way. Crucify MacMurfee if he don’t deliver. Crucify anybody who stands in your way. You hand me the hammer and the ten-penny and I’ll do it with my own hand. Crucify ‘em on the barn door! And don’t fan away the blue-bottles with any turkey wing!

Robert Penn Warren, All the King’s Men, 134

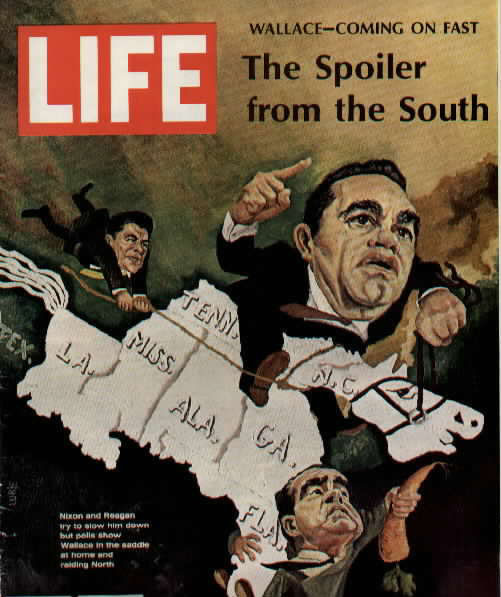

Charismatic leadership depends on resonance. Resonance in the US depends on understanding the predominant features of the common American White character and in relaying that understanding effectively. For examples on the political front, we would do well to reexamine American populists, especially figures like Huey Long and George Wallace, who, for a time, harnessed the “voice of a people” in response to the Eastern Establishment’s destructive incursions into their communities. They were extraordinarily talented, spontaneous public speakers. Popular prejudice short circuits considerations of these southerners, but see how charismatic and “on point” they are here, here, here, here, and here.

We desperately need leaders like them now.

Comments are closed.