Art in the Third Reich: 1933–1945 (Part 1)

This is a slightly edited version of an article was first published in Ecrits de Paris (Nr. 645, July-August 2002, L’Art dans l’IIIème Reich. Translated by the author.)

When writing about or discussing the plastic and figurative arts in Germany during the period from 1933 to 1945, one must inevitably mention the art that highlighted the epoch of National Socialism. During that short and troubled period of time, art was also a reflection of modern European history, and, therefore, it must be examined, or, for that matter, conceptualized, within the larger geopolitical framework of Europe as a whole.

National Socialist culture has always been a sensitive subject, whose controversial nature is more apparent today than ever before in the ongoing media warfare between so-called anticommunists and antifascists. If one accepts the conventional wisdom, widely accepted in all corners of he world, that National Socialism was a form of totalitarianism, one must then also raise the question as to whether there were any authentic cultural successes achieved during the Third Reich at all. Certain parallels can and should be drawn between artistic efforts in the U.S.S.R. and National Socialist Germany, in view of the fact that culture in both systems was dominated by a specific ideology. Does this therefore mean that there were no valuable works of art created in the U.S.S.R. or in National Socalist Germany? What both National Socialism and Communism had in common was the rejection of “art for art’s sake” (l’art pour l’art) and the repudiation of middle-class aestheticism. Instead, both political systems favored a committed and normative approach to art, which was supposed to be a tool for the creation of the “new man.” On the other hand, from the thematic, aesthetic and stylistic point of view, the differences between art in Communism and art in National Socialism were immense.

After the Second World War, as the result of pressure from the Allies, Germany was forced to open its doors to abstract art (Jackson Pollock, Piet Mondrian, et al.), and, consequently Germany had to stifle the production of its traditional figurative art. Even German artists who were not implicated in the National Socialist regime, including those whom the National Socialist propaganda had labeled “degenerate artists” (entartete Künstler) came under the ban. A large number of paintings and other works of art executed during the Third Reich were either removed or destroyed. Several hundred sculptures were demolished or trashed during the Allied air bombardments. After the war, a considerable number of works of art were confiscated by the Americans, because of “their pornographic character.” In the spring of 1947, 8,722 paintings and sculptures of German artists were transported to the United States. Of these, only a small number have been returned to the Federal Republic of Germany.

A short outline of art under National Socialism requires knowledge of the historical and political framework of that epoch. Who were those German artists? Were they sympathetic to the National Socialist regime? What did they do before the National Socialist seizure of power in 1933? What became of them after the fall of the Third Reich?

It is important to emphasize the fact that to be an artist in National Socialist Germany did not always imply self-enslavement to the ruling class or blind obedience to political decrees, nor did it necessarily entail membership in the National Socialist Party (N.S.D.A.P.). Yet to be able to have one’s artistic works accepted for public exhibition during the period between 1933 and 1945 presupposed at least tacit respect for the concept of beauty as defined by the National Socialist regime. A large number of German artists, who were by no means followers of the National Socialist regime, nevertheless well understood which type of works they could exhibit or display if they wished to remain within the public eye. As was the case with countless artists in every historical epoch and in all political systems from the dawn of time, many German artists were the simple, timorous types — the “flag wavers”, as it were, who understood that it was necessary to yield to the whims of the new regime if they did not wish to be left out of the spotlight completely.

Such a servile attitude is not a novel phenomenon in European cultural history. Being a good artist or a good writer does not always entail the artist’s possession of moral integrity, guaranteeing that the artist will always be found siding with the oppressed or shouting at full breath for universal justice. Throughout European history, there were (and still are) excellent artists and thinkers who served (and still serve) criminal governments. A well-known Croatian sculptor, Antun Augustinčić, who was influenced in his youth by the French sculptor Auguste Rodin, made busts of the Croatian pro-fascist Ustashi leader, Ante Pavelić. After World War II, in the new communist Yugoslavia, Augustinčić did the same thing for the communist ruler Marshall Josip Broz Tito. To ponder the question as to the moral and political integrity of the sculptor Augustinčić is one thing; to try to define the subtlety of his artistic achievements is quite another.

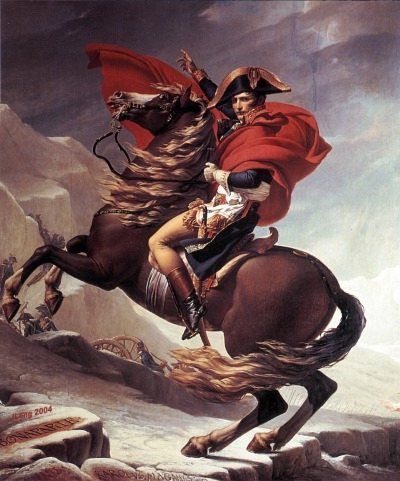

Moreover, any appreciation of an artistic work created during the National Socialist epoch requires a precise knowledge of the mentality of the German people, a good knowledge of the Zeitgeist, as it influenced a specific work of art at the very moment when it was created. Ignoring the dominant ideas of the first half of the twentieth century cannot help us more accurately to comprehend the artistic range of a particular artist. The famous French painter, Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825) served with devotion three widely different regimes: the French revolutionary Jacobins; Napoleonic imperialism; and, later, the reactionary monarchists of the French Restoration. David knew well how to adapt his skills to each new system (like that metaphorical and proverbial French demi solde — decommissioned officers from the former army of Napoleon who decided to serve the new rulers).

However, David’s lack of political or moral integrity does not belittle his gift for artistic composition or his powerful and realistic brushwork. One might be tempted to mention hundreds of similar cases today, notably when gifted artists and writers accept “political correctness” without any scruples and always with the full approval of their “good conscience.”

The Political Apparatus in the Service of Culture

It is often forgotten that the major goal of National Socialist propaganda was not the rearrangement of the political field, but rather the promotion of culture. This was especially true in the area of figurative and plastic art. The four most influential people in the Third Reich, i.e., Joseph Goebbels, Albert Speer, Alfred Rosenberg, and the Führer, Adolf Hitler, were focused, over the 12 years of the National Socialist regime, on the concept of the new art, the new architecture, and the new painting.

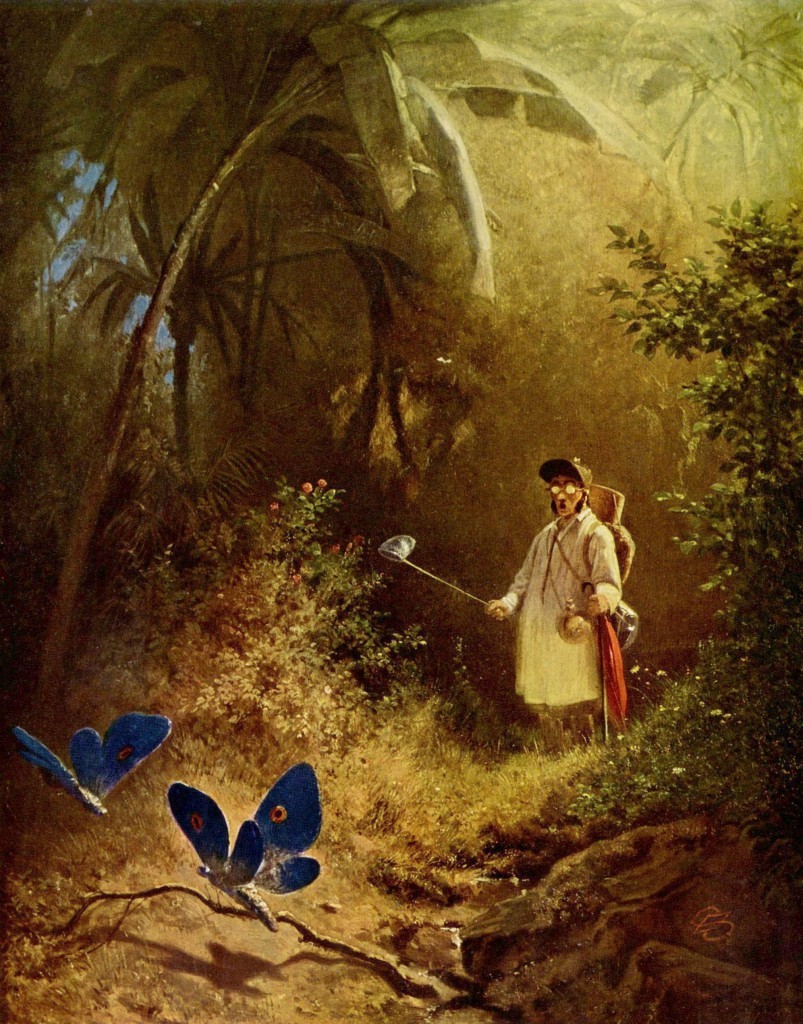

In his youth, at the beginning of the twentieth century, Hitler had painted hundreds of watercolors, some of which have, without doubt, a certain artistic value and seem to be held in high esteem among WWII artifacts dealers, especially in the United States. As a teenager, imbued by the art and culture of the period of Romanticism, Hitler was influenced by the watercolors of Rudolf von Alt and the oil paintings of Carl von Spitzweg. Toward the end of his reign, in 1945, Hitler dreamed of opening the largest art gallery in the world, which he had long determined to house in the Austrian city of Linz. Immense architectural and scientific efforts, such as the launching of the first model of the popular automobile named the “Volkswagen” and the construction of vast and well-designed autobans, were to a large extent Hitler’s own ideas. Nevertheless, he did not regard himself as a first-rate artist. In his answer to the editor in chief of the cultural newspaper Kunst dem Volk, on June 2, 1937, Hitler remarked: “The fact that I made paintings in order to survive, does not mean that they now deserve to be exposed in the Haus der Deutschen Kunst [The House of the German Art].”

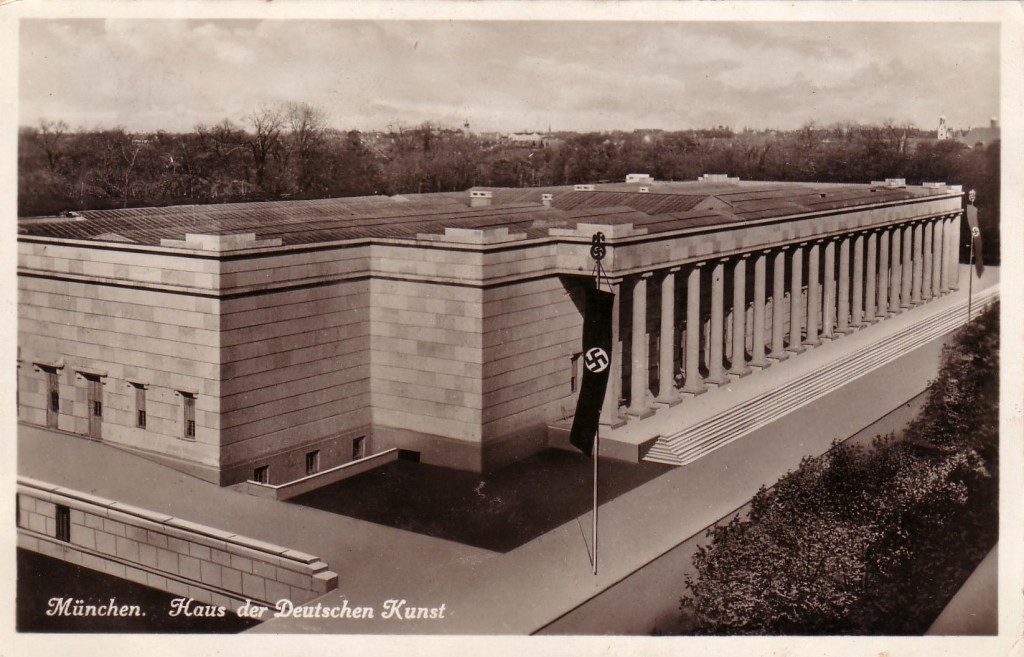

During the National Socialist regime many journals dealing with art were launched: Kunst der Nation, Kunst dem Volke, Die Kunst im Dritten Reich, etc. In 1937, the propaganda minister Goebbels inaugurated the “Chamber of Arts” (”Kunstkammer”), a cultural institution that, from 1935 to 1937, enrolled more than one hundred thousand members. During the period from 1933 to 1945, thirty large art exhibitions, on average, were held each month. This was the case even during the period from 1940 to 1945, when Germany was subject to the regular air bombardments carried out by the Allies. In 1937, the opening of the “Haus der Deutschen Kunst” took place in Munich. At that time this was the most significant establishment of its kind in Europe. The first stone of this building — which was 175 meters long — was laid by Hitler himself. Approximately, thousand German artists exposed their works in it from 1937 to 1939.

End of Part 1 of 2.

Dr. Tom Sunic (websites here and here) is author, translator, former US professor in political science and a member of the Board of Directors of the American Third Position. He is the author of Homo americanus: Child of the Postmodern Age, prefaced by Kevin MacDonald (2007). The third edition of his book Against Democracy and Equality; the European New Right, prefaced by Alain de Benoist, has just been released

Comments are closed.