Evil Genius: Constructing Wagner as Moral Pariah – PART 4

Go to Part 1.

Go to Part 2.

Go to Part 3.

Wagner and National Socialist Germany

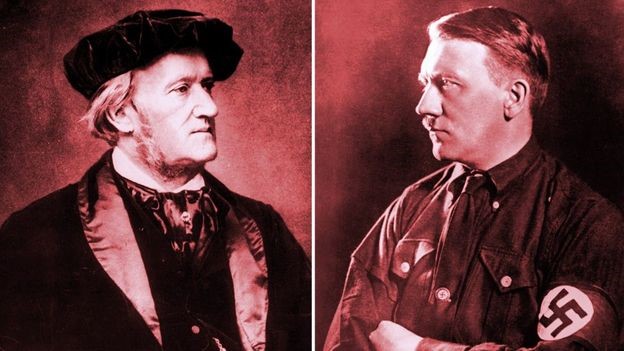

Richard Wagner has long been reviled by Jews as the intellectual and spiritual precursor to Adolf Hitler who, according to William Shirer, once declared: “Whoever wants to understand National Socialist Germany must know Wagner.”[1] This line is spoken by the Hitler character in the 2008 Hollywood film Valkyrie (the Wagnerian title of the film being taken from the codename for the failed Wehrmacht plot to assassinate Hitler in 1944). For music critic Larry Solomon, no other composer in history had a greater impact on world events than Richard Wagner; and “his devastating political legacy is second only to Adolf Hitler.”[2] In his book Anti-Semitism: A Disease of the Mind: A Psychiatrist Explores the Psychodynamics of a Symbol Sickness, Theodore Rubin states that a psychologically sick Adolf Hitler “borrowed from the almost equally sick anti-Semitic Wagner.”[3] Jewish activist and prolific writer on anti-Semitism, the late Robert Wistrich, likewise proposed that: “Wagner’s essentially racist vision of Jewry would have a profound influence on German and Austrian anti-Semites, including the English born Houston S. Chamberlain, Lanz von Liebenfels, and above all on Adolf Hitler himself.”[4]

This widely accepted notion of a direct intellectual line of descent from Wagner to Hitler has, however, been challenged by historians like Richard Evans who points out that “the composer’s influence on Hitler has often been exaggerated,” and that while Hitler “admired the composer’s gritty courage in adversity,” he “did not acknowledge any indebtedness to his ideas.”[5] Magee likewise maintains that “if one studies the intellectual development of the young Hitler one finds no evidence that he got any of his anti-Semitism from Wagner.”[6] While Evans and Magee slightly overstate their case, they are right to attempt to put the issue of Wagner’s influence on Hitler into a more rational perspective.

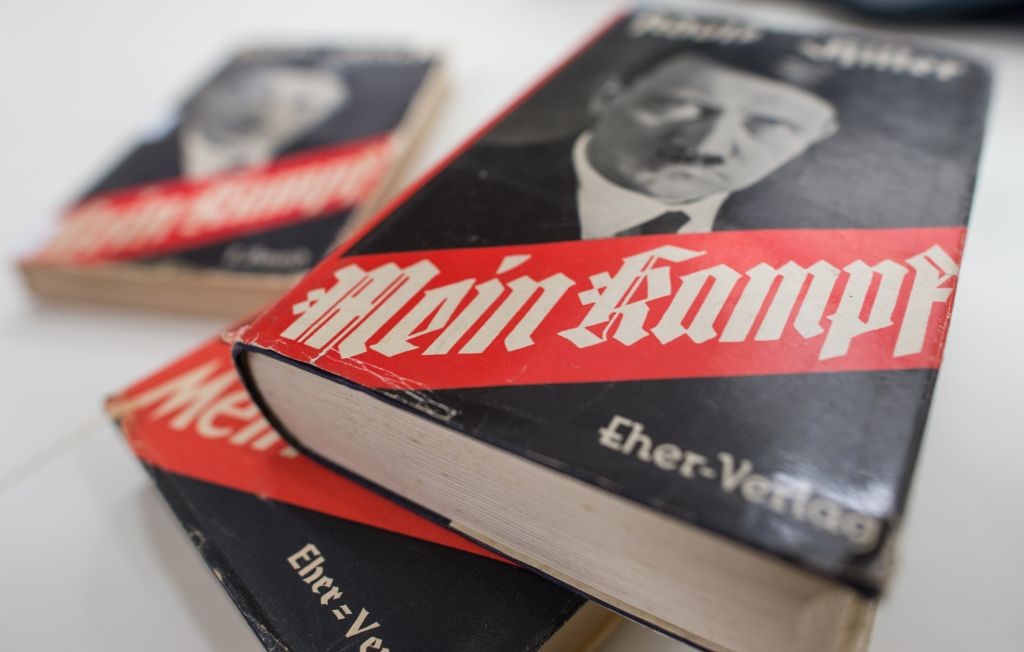

Wagner’s intellectual influence on Hitler was mainly secondhand through his son-in-law Houston Stewart Chamberlain, who developed some of Wagner’s ideas in his bestselling 1899 book The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century, which did influence Hitler’s ideas on race and the Jewish Question. The man who founded the library at the National Socialist Institute in Munich, Friedrich Krohn, compiled an inventory of the titles borrowed by Hitler between 1919 and 1921. The four page list contains over a hundred entries. Listed alongside Chamberlain’s Foundations of the Nineteenth Century is the German translation of Henry Ford’s The International Jew: The World’s Foremost Problem, and condensations of titles such as Luther and the Jews, Goethe and the Jews, Schopenhauer and the Jews, and Wagner and the Jew. Clearly Hitler had some exposure to Wagner’s anti-Jewish writing.[7] It is also clear that Hitler read and greatly admired Wagner’s autobiography, and the title of his book Mein Kampf (My Struggle) was conceivably modeled on Wagner’s Mein Leben (My Life).[8] According to German historian Guido Knopp, “It was not just the title, but also one of the key sentences, that Hitler copied from Richard Wagner. Just as the composer has written in Mein Leben: ‘I decided to become a composer,’ so did the prisoner [Hitler] now write: ‘I decided to become a politician.’”[9]

In his book Hitler’s Private Library: The Books That Shaped His Life, Timothy Ryback notes that among the books that found their way into Hitler’s vast private collection was a biography of Wagner by Chamberlain entitled Richard Wagner: The German as Artist, Thinker, Politician.[10] This book contains only a few minor references to Jews. In 1933, Hitler received a volume entitled Wagner’s Resounding Universe which was inscribed by its author, Walter Engelsmann, to “the steward and shaper of the descendants of Siegfried upon the earth.”[11] Among the books found in the bunker complex after the fall of Berlin in 1945 was a 1913 treatise on Wagner’s Parsifal.[12] Wagner’s ideas clearly exerted some influence on Hitler’s intellectual development. However, just three known volumes on Wagner (with none by Wagner himself) out of an estimated 16,000 books in Hitler’s collection at the time of his death, hardly suggests Wagner’s intellectual influence was “profound.”

There is certainly no evidence to support the extravagant claim of Joachim Fest in his biography of Hitler that: “Wagner’s political writing was Hitler’s favorite reading, and the sprawling pomposity of his style was an unmistakable influence on Hitler’s own grammar and syntax.” Fest even ventured to claim that Wagner’s “political writings together with the operas form the entire framework of Hitler’s ideology,” and that in these he “found the granite foundation for his view of the world.”[13] This assessment of Wagner’s influence on Hitler is utterly rejected by Jonathan Carr in his 2007 book The Wagner Clan. Carr makes the point that:

If Wagner’s works really were “the exact spiritual forerunner” of Nazism, surely the Fuhrer of all people would have drummed that point home ad infinitum. But one looks to him in vain not only for fascist interpretations of the music dramas but, stranger still, for direct references to the theoretical writings. There is, indeed, surprisingly little evidence that Hitler read Wagner’s prose works, though he evidently did borrow some from a library before he rose to power and the wording of some of his speeches indicates that he imbibed at least Das Judentum in der Musik. Why then did he not use the Master more clearly as an ally, especially in his anti-Semitic cause? In Mein Kampf, for instance, he notes that his early hostility to Jews owed much to the example set by Karl Lueger, the anti-Semitic mayor of Vienna. He also praises Goethe for acting according to the spirit of “blood and reason” in treating “the Jew” as a foreign element. He pays no similar tribute to the Master, indeed he only mentions Wagner by name once in the whole book (although he refers elsewhere to the “Master” of Bayreuth).[14]

In one of three brief references to Wagner in Mein Kampf, Hitler reflects on his early experiences attending Wagner’s operas: “I was captivated. My youthful enthusiasm for the Bayreuth master knew no limits. Again and again I was drawn to hear his operas, and today it still seems to me a great piece of luck that these modest productions in a little provincial city prepared the way and made it possible for me to appreciate the better productions later on.”[15] Among the “great men” in history that Hitler singled out in Mein Kampf were Luther, Frederick the Great, and Wagner. He praised Wagner as a “combination of theoretician, organizer, and leader in one person” which he regarded as “the rarest phenomenon of this earth. And it is that union which produces the great man.”[16]

Despite the paucity of evidence for Wagner having exercised the high level of intellectual influence on Hitler that is widely alleged, for the Jewish music writer David Goldman, Wagner’s name is eminently worthy of execration on the basis that he “mixed the compost heap in which the flowers of the twentieth century’s greatest evil took root.” According to Goldman:

The Nazis embraced Wagner not by accident or opportunism but because they recognized in him the cultural trailblazer of the world they set out to rule. … Wagner may not have been the only anti-Semite among the composers of the 19th century, nor even the worst, but he did more than anyone else to mold the culture in which Nazism flourished. The Jewish people have had no enemy more dedicated and more dangerous, precisely because of his enormous talent. In a Jewish state, the public has a right to ask Jewish musicians to be Jews first and musicians second. With reluctance, and in cognizance of all the ambiguities, I think the Israelis are right to silence him. [Goldman here refers to the unofficial ban on performances of Wagner’s music in Israel][17]

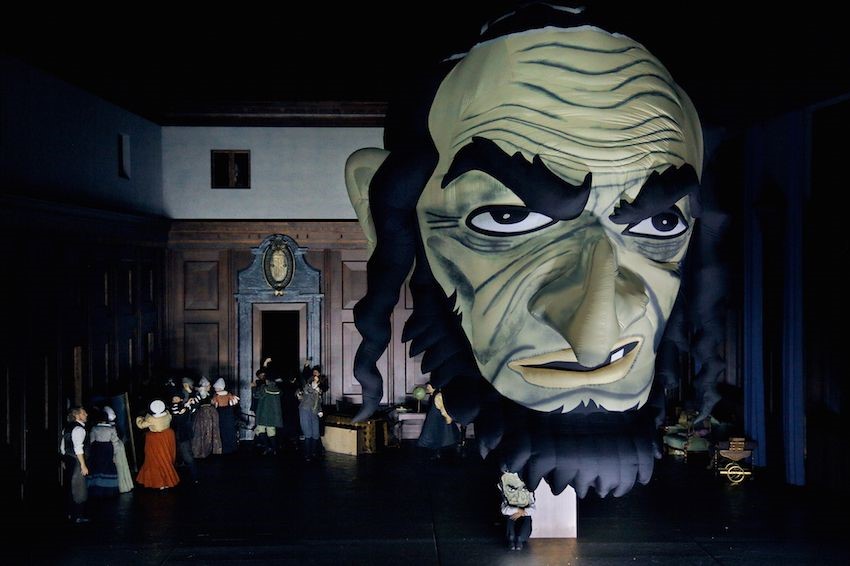

For Goldman, Hitler’s intellectual debt to Wagner and the “proto-Nazi” nature of Wagner’s musical dramas are unambiguous. Magee questions the idea that Wagner’s works inherently support National Socialist notions of heroism, and notes that Wagner’s last opera Parsifal (frequently cited as Wagner’s most “racist” opera) was denounced by the regime in 1933 for being “ideologically unacceptable” and was not performed at Bayreuth during the war.[18] Moreover, while Wagner’s music and operas were frequently performed during the Third Reich, his popularity in Germany actually declined in favor of Italian composers like Verdi and Puccini. In the theatrical year in which Hitler came to power, 1932–33, there were 1,837 separate performances of operas by Wagner in Germany. The number of performances then went steadily down until, by 1939–40, they were less than two-thirds of that figure, 1,154.[19] Evans notes that by the 1938–39 opera season, Wagner had only one opera in the top fifteen most popular operas of the season, with the list being headed by Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci.[20]

It is well known that the Berlin Philharmonic’s last performance prior to their evacuation from Berlin in April 1945 was of a scene from the conclusion to Wagner’s Götterdämmerung to an audience that included Speer, Dönitz and Goebbels. Likewise, when the Reich Radio announced Hitler’s death, the funeral march from Götterdämmerung was played. With these events in mind, Wagner’s music has been used in countless Third Reich documentaries—in the process consolidating the misleading impression that Wagner’s music was uniquely bound up with the cultural politics of the National Socialist state.

It is clear that the supposed National Socialist fascination with Wagner, to the extent it genuinely existed, was mostly Hitler’s inspiration. Hitler’s boyhood friend, August Kubizek, noted in his book The Young Hitler I Knew that what made the young Hitler so receptive to Wagner’s operas was not the composer’s political outlook, but rather Hitler’s own “constant, intensive preoccupation with the heroes of German mythology,” and Wagner’s ability to translate “his boyish dreams into poetry and music” which satisfied “his longing for the sublime world of the German past.”[21] Kubizek writes that, “listening to Wagner meant to him not a simple visit to the theater, but the opportunity of being transported into that extraordinary state which Wagner’s music produced in him, that trance, that escape into a mystical dream-world which he needed in order to sustain the enormous tension of his turbulent nature.”[22]

Kubizek describes the time they first went to a Wagner opera—Rienzi, an early work by Wagner that established him as a composer. “We were shattered by the death of Rienzi,” he writes of that fateful evening in 1906, “and although Hitler would usually begin to talk immediately after being moved by an artistic experience, and to voice sharp criticism of the performance, on this occasion Adolf remained silent for a long time.” Rienzi was a Roman who rose to be tribune of the people but was then betrayed and died within the ruins of the Capitol. Kubizek described how his friend suddenly announced with “grand and thrilling images,” how he would lead the German people “out of servitude to the heights of freedom.”[23] According to Kubizek, Hitler’s decision to become a politician “was seized in that hour on the heights above the city of Linz,” when “in a state of complete ecstasy and rapture,” he transferred the character of Rienzi “to the plane of his own ambitions.”[24] Describing that fateful night to Winifred Wagner in 1939, Kubizek claims that Hitler solemnly declared “In that hour it began!”[25]

Hitler heard Tristan and Isolde at least thirty or forty times during the Vienna phase of his life. At one stage, he even wrote a brief sketch for a Wagner-style opera entitled Wieland the Smith. Gretl Mitlstrasser, the woman who managed the daily running of the Berghof “recounted numerous stories of Hitler’s private ‘communing’ on the property… when he held late-night vigils on the Berghof balcony, watching the Untersberg bathed in moonlight; when he let the ethereal strains of Wagner’s Lohengrin fill his study as he watched the jagged cliffs peek through the enfolding mists.”[26] Hitler had a bust of Wagner by Arno Breker in his private quarters, and in his table talk once claimed that “when I listen to Wagner I hear the rhythms of a bygone world.”[27]

In the 1920s, Hitler became a friend of Wagner’s children and grandchildren, and particularly of his English-born daughter-in-law Winifred, who joined the NSDAP in 1926, and who proposed marriage to him. She later wrote that “the bond between us was purely human and personal, an intimate bond founded on our reverence and love for Richard Wagner.”[28] In the summer of 1933 she found that hundreds of foreign ticket reservations for that year’s Bayreuth Festival had been cancelled, threatening its financial viability. Lieselotte Schmidt, a close friend of Winifred, noted at the time that “we have been frozen into isolation. The hate campaign against Bayreuth, which is at root of purely Jewish origin, stops at nothing in its lies and unpleasantness.” When the matter came to Hitler’s attention, he summoned Winifred to Berlin, and Schmidt noted that: “She flew there, and within a quarter of an hour we had the necessary help—and how!” The festival was made exempt from all taxes during the Third Reich, and Hitler donated 50,000 Reichsmarks of his own money for each new production.[29]

Wagner’s grandson and daughter-in-law with Hitler

Wagner’s grandson and daughter-in-law with Hitler

Evans points out that Hitler’s personal patronage meant that “neither Goebbels nor Rosenberg nor any of the other cultural politicians of the Third Reich could bring Bayreuth under their aegis.”[30] Winifred Wagner and the managers of the Festival were “granted an unusual degree of cultural autonomy” by Hitler, and Knopp states that “It is a fact that even the Bayreuth productions during the Nazi era hardly display any evidence of distortion for propaganda reasons.”[31] Hitler was a regular guest at the Bayreuth festivals between 1933 and 1939, and on his fiftieth birthday Winifred arranged for him to be presented with the manuscript draft to Wagner’s Rienzi and original scores of Das Rheingold and Die Walküre, as well as a sketch for Götterdämmerung.[32]

When considering Wagner’s posthumous relationship with the National Socialists, we need to draw a clear distinction between Hitler as an individual and the Third Reich as a regime. Magee is careful to do so:

It was not the case that the Nazi regime in general was devoted to Wagner, or did anything to promote his works. Many people nowadays write and talk as if Wagner provided a sort of sound-track to the Third Reich, and that on organized party occasions there was always, or usually, Wagner. This conception has become a cliché on film and television, where it is usual for any depiction of the Nazis to be literally accompanied by Wagner’s music, for preference at its most brassy and bombastic, as in the Ride of the Valkyries or the Prelude to Act III of Lohengrin, and played very loud. The whole picture that this conjures up, and is meant to conjure up, is false.

Supporting this thesis, Evans maintains that there was a “lack of interest” in Wagner “on the part of almost everyone in the Party leadership except Hitler himself.”[33] In 1933, Hitler ordered that each Nuremberg Rally would open with a performance of Die Meistersinger, although these performances were very unpopular with other Party functionaries who had be ordered to attend. Evans notes that when Hitler “entered his box he found the theater almost empty; the party men had all chosen to go off to drink the evening away at the town’s numerous beer halls and cafes rather than spend five hours listening to classical music. Furious, Hitler sent out patrols to order them out of their drinking-dens, but even this could not fill the theater. The next year was no better. … After this Hitler gave up and the seats were sold to the public instead.”[34]

While Joseph Goebbels seems to have shared some of Hitler’s affinity with Wagner, and often visited Bayreuth, his diaries reveal no special insights into Wagner’s works or ideas, and nor do his public speeches. He praised Die Meistersinger as “the incarnation of all that is German.” It contained everything “that defines and fulfills the cultural soul of Germany.”[35] The 1933 Bayreuth Festival was opened by Goebbels with the words: “There is probably no work so close in spirit to our age and its intellectual and psychological tensions as Richard Wagner’s Die Meistersinger. How often in recent years has its rousing chorus, ‘Wacht auf, es nahet gen dem Tag’ (Awake for morn approaches), echoed the faith and longing of Germans, as a tangible symbol of the reawakening of the German people from the deep political and spiritual slumber coma of 1918.”[36]

Joseph Goebbels attending the Bayreuth Festival in 1937

Joseph Goebbels attending the Bayreuth Festival in 1937

Albert Speer, Hitler’s personal architect, and later also his armaments minister, was another Bayreuth regular, ostensibly motivated more by duty than genuine interest. He notes in his memoirs that Hitler often discussed Wagner with Winifred and seemed to know what he was talking about. Evidently Speer did not know enough to be sure.[37] For the leading ideologist of the party, Alfred Rosenberg, the real National Socialist musical model was Beethoven who “took fate by the throat and acknowledged force as the highest morality of man. … Whoever understands the essence of our movement knows that there is a drive in us all like that which Beethoven embodied to the highest degree.” While he also believed Wagner embodied the strength of the “Nordic soul,” Rosenberg criticized the composer’s Gesamtkunstwerk approach, noting that “the inner harmony between word content and physical content is often hindered by the music. … An attempt to wed these forces destroys spiritual rhythm and prevents emotive expression.”[38]

Rosenberg was certainly not alone in his view. The general manager at Bayreuth during the Third Reich, Hans Tietjen, made the point after the war that “In reality, the leading party officials throughout the Reich were hostile to Wagner. … The party tolerated Hitler’s Wagner enthusiasm, but fought, openly or covertly, those who, like me, were devoted to his works—the people around Rosenberg openly, those around Goebbels covertly.”[39] Aside from the hostility to Wagner grounded in aesthetics and ideology, Carr makes a more general point:

The truth is that many Nazis, in high and low places, were bored to tears by Wagner. There is nothing very odd about that. Lots of people past and present who may well have a certain interest in other music will run a mile to escape a seemingly interminable evening with the Master. Too few tunes, too many scenes in which people stand about for ages apparently doing nothing much. The point is only worth stressing here because the Nazis are reputed to have had a special affinity to Wagner’s music. The evidence suggests this was simply not so.[40]

It has been sometimes alleged that Wagner’s music provided a “soundtrack to the Holocaust” and was played at concentration camps during wartime. The German historian Guido Fackler claims that Wagner’s music was sometimes used at the Dachau concentration camp in 1933 and 1934 to “reeducate” political prisoners through the beneficial exposure to nationalistic music.[41] There is, however, no documentary evidence supporting claims that Wagner’s music was used in this way during the war. Larry David mocked this urban legend (and the unhealthy Jewish obsession with Wagner) in an episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm where he is rebuked by a Jewish stranger for whistling a Wagner tune in the street.[42]

Conclusion

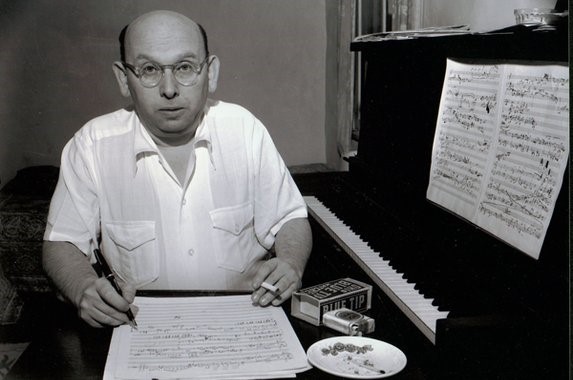

The ethno-political motivation that underpins the construction of Richard Wagner as moral pariah is exemplified by the contrasting way that Jewish commentators have reflected on the life and legacy of the Jewish composer Hanns Eisler who once declared Wagner to be “a great composer, unfortunately.” A committed Marxist, Eisler began in 1930 a long-standing collaboration with the poet and playwright Bertolt Brecht. With Hitler’s ascent to power, Eisler left Germany and eventually settled in Hollywood, where he was nominated for Oscars for writing the music for the films Hangmen Also Die (1942) and None but the Lonely Heart (1944). In 1947, Eisler appeared before the Un-American Activities Committee, and despite the intercession of Albert Einstein, Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein, was deported to East Germany in 1948 where he remained for the rest of his life, writing music for the totalitarian state (including its national anthem, and the Comintern anthem). Eisler collaborated with T.W. Adorno in 1947 to produce the book Composing for the Films. Instead of reproaching Eisler for his ardent commitment to a regime and ideology that destroyed millions of lives, Jewish commentators invariably portray him as the innocent victim of the anti-Semitism of the Third Reich, and then of the HUAC hearings and the Hollywood blacklist.

Jewish communist composer Hanns Eisler

Jewish communist composer Hanns Eisler

The Jewish-dominated intellectual and media elite eagerly invoke Wagner’s life and legacy as a salutary lesson in the evils of anti-Semitism and White nationalism. Constructing Wagner as moral pariah allows the composer and his works to be constantly used as a springboard for intensive reflections on “the Holocaust,” the evils of white racial feeling, and the moral necessity of state-sponsored multiculturalism and mass non-White immigration to the West. Only these policies, after all, will ensure that Wagner’s “morally loathsome” intellectual legacy (which amounts to a proposal for a European group strategy in opposition to Judaism) can never again find a receptive White audience—by progressively doing away with White people altogether.

In the meantime, the construction of Wagner as an anti-Semitic exemplar and moral pariah ensures the composer, whose achievement far surpasses that of any Jewish composer, can never become a locus of White racial pride and group cohesion. Richard Wagner has been a particular target for Jewish denigration because of his strong and unashamed ethnic and racial identification, and for his willingness to publicly oppose Jewish influence. This, together with his status as one of the most stupendous musical geniuses that the world has ever seen, endows him with rich potential to re-emerge as a rallying point for White Nationalists. The rebirth of a strong sense of racial feeling among White people will be greatly aided by reclaiming cultural heroes like Richard Wagner from the manufactured taint of moral censure that distorts their popular remembrance.

Brenton Sanderson is the author of Battle Lines: Essays on Western Culture, Jewish Influence and Anti-Semitism, banned by Amazon, but available here and here.

[1] William Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (New York: Random House, 2002), 101.

[2] Solomon, “Wagner and Hitler,” op. cit.

[3] Rubin, Anti-Semitism: A Disease of the Mind, 127.

[4] Robert S. Wistrich, Anti-Semitism: The Longest Hatred (London: Thames Mandarin, 1992), 56.

[5] Richard Evans, The Third Reich in Power (New York, Penguin, 2005), 199.

[6] Magee, Wagner and Philosophy, 362.

[7] Timothy Ryback, Hitler’s Private Library: The Books That Shaped His Life (New York: Vintage, 2010), 50.

[8] Guido Knopp, Hitler’s Women, trans. by Angus McGeoch (Phoenix Mill: Sutton, 2003) 158.

[9] Ibid., 169.

[10] Ryback, Hitler’s Private Library, 134.

[11] Ibid., 146.

[12] Ibid., 239.

[13] Joachim Fest, Hitler (London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1992), 56.

[14] Carr, The Wagner Clan, 187.

[15] Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, trans. by James Murphy (Bottom of the Hill, 2010), 23.

[16] Ibid., 488.

[17] David Goldman, “Muted: Performances of Wagner’s music are effectively banned in Israel. Should they be?” op. cit.

[18] Magee, Wagner and Philosophy, 366.

[19] Ibid., 365.

[20] Evans, The Third Reich in Power, 201.

[21] August Kubizek, The Young Hitler I Knew, trans. by Geoffrey Brooks (London: Greenhill Books, 2006), 84.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid., 118.

[24] Ibid., 116-8.

[25] Ibid., 118-9.

[26] Ryback, Hitler’s Private Library, 176.

[27] Nicholson, Richard and Adolf, 21.

[28] Knopp, Hitler’s Women, 152.

[29] Ibid., 181.

[30] Evans, The Third Reich in Power, 200.

[31] Knopp, Hitler’s Women, 189.

[32] Ibid., 193.

[33] Evans, The Third Reich in Power, 201.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Knopp, Hitler’s Women, 184.

[36] Ibid., 182.

[37] Jonathan Carr, The Wagner Clan, 184.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Quoted in Magee, Wagner and Philosophy (London: Penguin, 2000), 366.

[40] Jonathan Carr, The Wagner Clan, 184.

[41] Guido Fackler, “Music in Concentration Camps 1933-1945,” trans. by Peter Logan, Music & Politics, Undated. http://www.music.ucsb.edu/projects/musicandpolitics/archive/2007-1/fackler.html

[42] To view this scene see: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_nS66Ivbvc

Jewish Opera director Barrie Kosky

Jewish Opera director Barrie Kosky

Arturo Toscanini with the Palestine Symphony Orchestra

Arturo Toscanini with the Palestine Symphony Orchestra

Ludwig Geyer

Ludwig Geyer

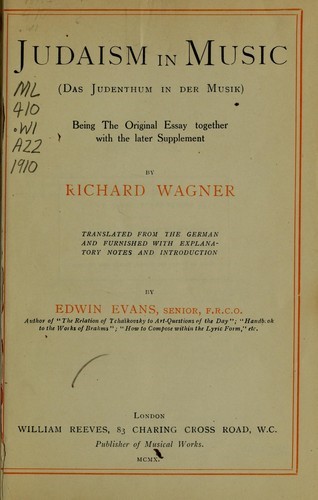

A 1910 English language edition of Judaism in Music

A 1910 English language edition of Judaism in Music Richard Wagner

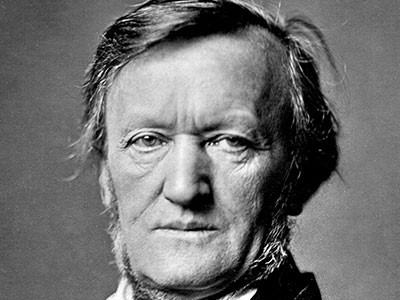

Richard Wagner

“Why not make the Jew a bounder in literature as well as in life? Do Jews always have to be so splendid in writing?”

“Why not make the Jew a bounder in literature as well as in life? Do Jews always have to be so splendid in writing?”