Celebrating America’s European Heritage: Leif Erikson

Joseph F. Healey has pointed out that White ethnic identities are evolving into new shapes and forms, merging the various “hyphenated” ethnic identities into a single, generalized “European American” identity based on race and a common history of immigration and assimilation. In light of the fact that virtually every minority group has generated a protest movement — Black Power, Red Power, Chicanismo — proclaiming a recommitment to its own heritage and to the authenticity of its own culture, European Americans should seize the opportunity to reclaim their ethnic and historical heritage on festive October occasions such as Columbus Day (Oct. 12) and Leif Erikson Day (Oct. 9).

Regarding Columbus, it should be remembered that the great Admiral of the Seas may well have had knowledge of earlier Norse explorations. In 1477 he sailed to Ireland and Iceland with the merchant marine, as attested by his son, Fernando, who quotes a note of his father stating:

I sailed in the year 1477, in the month of February, a hundred leagues beyond the island of Tile [Thule, i.e. Iceland], whose northern part is in latitude 73 degrees north and not 63 degrees as some would have it … the season when I was there the sea was not frozen.

In all societies with a history of migrations, the question “who came first?” becomes important. Centuries before Columbus and the Waldseemüller world map known as “America’s baptismal certificate,” the Icelandic sagas answered this question by immortalizing the names and deeds of the pioneers for posterity.

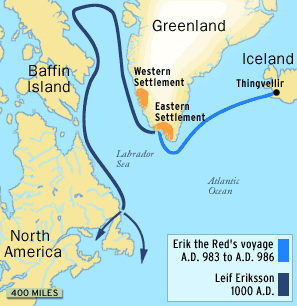

Kirsten A. Seager has emphasized the “tremendous energy and momentum” indicated by the fact that the comparatively rapid colonization of Iceland and Greenland took place while the Norse were also tightening their grip on the British Isles. Indeed, the discovery of new lands in the West by the Northmen came about in the course of the great Scandinavian exodus of the 9th, 10th and 11th centuries when Vikings “swarmed over all Europe,” ruling the high seas, conquering kingdoms, founding colonies and empires. In these centuries waterborne Vikings exploded out of their native lands to trade, raid, and settle all the way “from the Pillars of Hercules to the Ural Mountains.” The main stream of Norsemen took a westerly course, striking Great Britain, Ireland and the Western Isles, ultimately to reach Iceland (in 874 A. D.), Greenland (in 985) and North America (in 1000 AD).

Leif Erikson’s father, Erik the Red, was the founder of the first European settlement on Greenland. A few years earlier, he had, together with his father Thorvald, left his native Norway for Iceland because of a murder they had committed in Norway. After having married Thjodhild, the tough-minded daughter of a well-to-do Icelandic farmer, Erik once again killed two men, and was banished from his home in Haukadal, Iceland. He then settled on an island in the Icelandic Breidafjord and, while there, he lent his bench boards to a man who refused to return them when asked. Quarrels and fights ensued, and Erik was outlawed for three years for having killed that man, probably around AD 983. Even if “his temper matched his hair colour”, as Seaver assumes,

his solid family background [he was a fifth-generation descendant of the Norwegian chieftain Öxna-Thorir, and thus related to the Viking Nadd-Odd, the discoverer of Iceland] and his experience as a mariner, in addition to personal attributes … made him an able planner and administrator and a forceful executive … a dynamic, well-connected leader who would have been fully aware of the general knowledge of his own time and place. (Seaver 2010, 16)

His skills and qualities proved useful when he decided to explore the land to the west (Greenland), across some of the world’s most dangerous seas. The Greenland settlers encountered no other inhabitants, though they explored to the northwest, discovering Disko Island. (A small, but incontestable piece of evidence for the Norse Greenlanders’ High Arctic voyages is a small rune stone found in connection with three cairns on the island of Kingittorssuaq, directly opposite the entrance to Lancaster Sound — the eastern end of the Northwest Passage). Of the 25 open, square-rigged ships that sailed from Iceland, only 14 ships and 350 colonists are believed to have survived to reach their destination — an area in Greenland later known as Eystribygd (Eastern Settlement). By the year 1000 there were an estimated 1,000 Scandinavian settlers in the colony, but an epidemic in 1002 considerably reduced the population.

Twelfth- and thirteenth-century Icelandic sagas report — based on oral traditions and genealogies whose kernel of historicity were preserved for many generations — that Erik the Red gave the island its name — Greenland — as a marketing strategy designed to disguise its harsh environment and make it attractive to would-be colonists. Accustomed to hard, physical work and experts at exploiting the natural resources in the Far North, the pioneers were remarkably successful throughout the five centuries that passed “before smoke no longer rose above the turf-covered roofs of their settlements.” The settlement died out for unknown reasons (suggestions include “genetic deterioration, malnutrition, incompetent resource exploitation, fatal skirmishes with encroaching Inuit, failure to learn from the Inuit, pestilence brought from Europe, pirates descending from Europe, isolation from Europe, the breakdown of an already fragile social order, an eastward return to Iceland and Norway and last, but certainly not least, climate change” [Seaver 2010, 8–9]).

The two Vínland sagas represent the subsequent events somewhat differently, but both sagas make it clear that Erik the Red and his family provided the initiative as well as the leadership for all of the early expeditions. The captains on the voyages commemorated by the Vínland sagas were his sons or other members of his immediate circle, such as the visiting Icelandic merchant Thorfinn Karlsefni Thordsson (who was married to Gudrid, the widow of Leif’s brother Thorstein). Leif was the first to launch an expedition, followed by expeditions headed by his brothers Thorvald and Thorstein, one led by his sister Freydis, and one by Karlsefni.

The second of three sons of Erik the Red, Leif “the Lucky” Erikson (d. 1025) sailed from Greenland to Norway in the year 999 AD, where he was converted to Christianity by the Norwegian king Olaf Tryggvason. Leif “the Lucky” joined the king’s body-guard, but was shortly afterwards commissioned by Olaf to urge Christianity upon the Greenland settlers. On returning to Greenland, he proselytized for Christianity and converted his mother, who built the first Christian church in Greenland (her husband, Erik the Red, remained true to the ancient Germanic gods). The Norse — as did the Continental Franks, according to Ricardo Duchesne (2011, 370) — continued to fight in the berserker style (frenzied intensity, with no concern for personal survival), unhindered by a version of Christendom that gave Christ qualities of the Germanic war god Odin/Woden. Speidel (2004, 33) observes that “northern and southern Germanic lands shared warrior styles and heroic myths.” By 1053 — despite the polytheistic preferences of the Norse — the Christian church was well enough established to warrant inclusion in the Archbishopric of Hamburg—Bremen since Pope Leo IX includes it in a bull dated 6 January 1053, the earliest known reference to Greenland by name.

Leif Erikson first learned of Vinland from the Icelander Bjarni Herjulfsson — “a man of great promise,” according to the Saga of the Greenlanders. Fourteen years earlier he had become the first European to sight mainland America when his Greenland-bound ship was blown westward off course. He apparently sailed along the Atlantic coastline of eastern Canada but did not go ashore. In the year 1000 AD a crew of 35 men led by Leif Eriksson set out to find the land sighted by Bjarni. The sagas refer to three territories: Helluland (“Flat-Stone Land,” probably Baffin Island), Markland (“Forest Land,” probably Labrador) and Vinland (“Wine Land”) — usually thought to have been located in the area around the Gulf of St Lawrence, possibly New England or New Brunswick.

A German crewman on board Leif Erikson’s ship is said to have been the first to associate the new land, Vinland, with wine:

In the beginning Tyrkir spoke for some time in German, rolling his eyes, and grinning, and they could not understand him; but after a time he addressed them in the Northern tongue: “I did not go much further [than you] and yet I have something of novelty to relate. I have found vines and grapes.” “Is this indeed true, foster-father?” said Leif. “Of a certainty it is true,” quoth he, “for I was born where there is no lack of either grapes or vines.”

The Norse enthusiastically filled their ships with grapes and cut vines and timber besides. By the time they left for Greenland the following spring, they had an excellent cargo and were so pleased with their venture that Leif “named the country after its natural qualities and called it Vínland” (Seaver 2010, 53).

Thorfinn Karlsefni also reported that he found “wine berries” growing there, and these were later interpreted to mean grapes. Seaver (2010, 50ff) emphasizes that, given the fact that the Norse had been trading with and on the European continent for several centuries when they set out to explore North America, they knew very well the ingredient required for making wine. Vinland cannot be equated with the grapeless Newfoundland, whose Viking site seems to have functioned as a trans-shipment station for American goods intended for Greenland-based trade. The houses at L’Anse aux Meadows at the northernmost tip of Newfoundland are now widely believed to represent Leif Erikson’s “strategically selected wintering camp, used and expanded for a while by subsequent skippers and crews, much as implied by the sagas” (ibid).

When the good news had been reported back home, Leif ’s brother Thorvald became the next to go across to Vínland. The new group of explorers settled there for the winter. The next spring, they explored the country further by ship. The following summer, Thorvald and his men ran into nine members of an indigenous Beothuk tribe who were hiding under some skin-covered boats. The Norse killed eight of the natives, but the ninth got away only to return with a swarm of skin boats approaching the intruders. Seager’s description of the march of events deserves to be quoted at length:

During the ensuing battle, Thorvald Eiriksson suffered a mortal wound, and his men buried him in accordance with his wishes before they rejoined the other members of their expedition. Next, says the ‘Saga of the Greenlanders’, they gathered grapes and vines, spent another winter at Leif ’s houses and in the spring returned to [Greenland], where Leif was now in charge after [Erik the Red’s] death. Although both of the Vínland sagas note that the third brother, Thorstein Eiriksson, had married Gudrid Thorbjörnsdaughter, only the ‘Saga of the Greenlanders’ reports that Thorstein, accompanied by his wife, made an abortive attempt to reach Vínland and bring back Thorvald’s body. Both sagas agree that Thorstein soon died up in the Western Settlement, and the ‘Saga of the Greenlanders’ notes that his young widow, an intelligent woman ‘of striking appearance’, then returned down to the Eastern Settlement to stay with her brother-in-law Leif. While there, she soon found favour with the visiting Icelandic merchant Thorfinn Karlsefni, ‘a man of considerable wealth’. He had arrived at Brattahlid prepared for trade and was invited to spend the winter with Leif, so he had ample opportunity to appreciate Gudrid’s sterling qualities. They were married that same winter. There was still much talk about Vínland, and at the urging of his bride and many others, Karlsefni decided to make the crossing himself and to consider the possibility of a permanent settlement over there. Sixty men and five women, Gudrid included, went along, bringing some livestock, and they arrived safely at Leif ’s houses. Both people and animals found plenty to eat, and they passed a busy, but uneventful winter. Change came the following summer, when a large number of natives suddenly appeared and became so frightened by the visitors’ bellowing bull that they tried to enter the Norse houses, from which they were immediately barred. When the situation eventually cooled down, it transpired that the natives were hoping to barter furs and pelts for Norse goods, preferably weapons. In the ‘Saga of the Greenlanders’ version of Karlsefni’s first interaction with North American natives, he forbade his men to sell arms, however, and ordered the women to bring out milk instead. The ‘Saga of Eirik the Red’ for its part describes pre-Karlsefni crossings only perfunctorily in a reference to Vínland ‘where, it was said, there was excellent land to be had’. Having recently married Gudrid, Karlsefni decided to mount an expedition across the strait, and he left with two ships carrying full crews consisting primarily of Icelanders, as well as with a third ship with mostly Greenlanders on board, including Thorvald Eiriksson, Eirik’s son-in-law Thorvard and Thorvard’s wife, Freydis Eiriksdaughter. After making their way via the Western Settlement to the other side, the explorers spent a tough first winter in the new land, camping in a place they called Straumfjord (Current Fjord), which has proved as contentious a location as Vínland itself. Nowhere in this saga is there any mention of the houses Leif had built, because Leif ’s role in this version had merely been to spot the new coasts first and subject them to only a brief inspection ashore before heading home to Greenland. (K. A. Seaver, Last Vikings: The Epic Story of the Great Norse Voyagers, (London: I.B. Tauris, 2010), pp. 53–55)

Thorfinn Karlsefni’s colonizing expedition, encouraged by the reports of grapes growing wild, followed the coastline southward until they reached a heavily wooded region, perhaps some part of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and settled there. Ten of his crew sailed north, supposedly in search of Vinland, while Karlsefni wanted to go south, where he reckoned the country was likely to improve. The remaining men decided to go with him and felt rewarded when they found wild wheat growing on the low ground and grapevines on the higher ground, and there were fish and game aplenty as well as grazing for the livestock they had brought with them. After two weeks of tranquility, a number of skin boats suddenly appeared, carrying men who made much noise by waving sticks:

The Norse went down to meet them, and the newcomers came ashore to get a close look at the intruders in their land, stared their fill and got back in their boats and rowed away. Karlsefni and his people subsequently built a settlement on a slope by the lakeside and spent a pleasant winter there, with no snow and with the livestock able to fend for themselves. … One morning in the spring, such a large number of skin boats approached from the south that ‘it looked as if the estuary were strewn with charcoal’, and sticks were being waved from every boat as on the first occasion. The Norsemen ‘raised their shields and the two parties began to trade’. As in the ‘Saga of the Greenlanders’ story, weapons were high on the natives’ wish list, but they reportedly also wanted to buy red cloth, which Karlsefni was happy to trade for grey pelts until every scrap of cloth was gone. Just at that moment, the bull belonging to the Norse came charging out of the wood with furious bellows, and the terrified natives ran to their boats and rowed away. Three weeks went by with no further sight of them, but when they returned, they came in such numbers and howled so furiously that Karlsefni realised they were primed for battle. (Seaver 2010, 55–56)

In the fierce battle that followed, four natives and two of the Norsemen died. Leif Erikson’s pregnant sister Freydis is portrayed in the sagas as a berserker personality steeled with willpower and strength of character that makes the Wagnerian Walkyries look like a group of extras. Pursued and encircled by hostile Natives (“Skraelings”), she snatched the sword of a slain Viking to defend herself: “she stripped down her shift, and slapped her breast with the naked sword. At this the Skraelings were terrified and ran down to their boats, and rowed away.” No wonder Michael Speidel (2004, 76) judges Freydis as “one of the last known berserks.”

Another prominent woman in the Saga of Erik the Red, Thorfinn Karlsefni’s wife Gudrid (the widow of Leif’s brother Thorstein) gave birth to a son, Snorri (born c. 1005) — the first European born in America. By the time they had stayed there three years, the colonists’ trade with the local Native Americans had turned into full-scale warfare, and so the colonists returned to Greenland.

Despite the failure of their efforts to establish a permanent presence in North America, the Norse did make later visits to Vinland to secure materials, and stray finds have turned up in the excavation of native American sites, including a late eleventh-century Norwegian coin found on the central Maine coast (the coin was minted in Norway between 1065 and 1080 during the reign of King Olaf III). An Icelandic chronicle, Skálholtsannáll (1347), makes reference to a Greenland-ship that had been to Markland on a timber-gathering expedition. Timber for shipbuilding was crucial to the Norse, and both Iceland and Greenland were largely deforested.

The Vinland name entered the literature of continental Europe, almost certainly first in 1075 through the History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen written by Adam von Bremen. Adam mentioned Vinland on the authority of King Sven II Estridsen of Denmark, who told of Iceland, Greenland, and other lands of the northern Atlantic known to the Scandinavians. Adam says of King Sven:

He [the king of the Danes] spoke also of yet another island of the many found in that ocean [where Greenland lies]. It is called Vinland because vines producing excellent wine grow wild there. That unsown crops also abound on that island we have ascertained not from fabulous reports but from the trustworthy relation of the Danes. Beyond that island, he said, no habitable land is found in that ocean, but every place beyond it is full of impenetrable ice and intense darkness.

It has been suggested that the Icelandic colony — from which the Vinland explorers emerged — was “an interesting forerunner of the American republic, having a prosperous population living under a republican government, and maintaining an independent national spirit for nearly four centuries.” The western world’s first parliament — the Althing — was established in Iceland. It has convened every year without exception since the early 10th century.

The Norse 10th-century colonization of Greenland, and their 11th-century voyages to North America, “mark the farthest reach of the medieval Norse quest for land and livelihood” (Seaver 2010, 1). This medieval expansion of European “Lebensraum,” establishing footholds in the New World, can also be seen in the Norman march eastward to create Western European states in the Mediterranean (Castile, Portugal, Cyprus, Jerusalem, Sicily), and in the settlement of German knights, Frankish and Dutch colonists in Eastern Europe that gathered momentum from the eleventh century onwards. In this period, the northern and western isles of Britain, northern Scotland, and the North Atlantic isles (the so-called insular Viking zone) became part of what Peter Heather has called “a Scandinavian commonwealth,” the lingua franca of which was, it has been suggested (at least in the Anglo-Saxon lands), an Anglo-Scandinavian dialect.

The Vikings are still commemorated by annual festivals such as Up Helly Aa, held on the last Tuesday in January, in the depths of winter darkness in the Far North. The day begins with the year’s elected Jarl (earl or leader), and his fifty-seven-strong retinue of guizers marching through the streets of Lerwick dressed in scarlet velvet, wearing winged helmets and carrying elaborate shields and heavy war axes.

Becoming the Jarl of Up Helly Aa is a great honor. The Jarl assumes the name Sigurd Hlodvisson for the day and receives the freedom of Lerwick for the duration of his twenty-four-hour reign. The culmination of Up Helly Aa is the ceremonial torching of Sigurd’s galley Asmundervag, specially made for the occasion. The real Sigurd Hlodvisson, also known as Sigurd the Stout, lived from 980 to 1014. Sigurd was the Norse Earl of Orkney and divided his time between visiting his overseas dominions, in Ireland and the Isle of Man, and summers spent raiding the Hebrides and the Scottish mainland. During these raids, the magic raven banner of Odin, belonging to Sigurd’s grandfather Einar (the son of Earl Ragnvald of More, Norway), might have been seen blowing in the wind, depicting a raven in full flight. The raven was the symbol of Odin, and its magic ensured the victory of the army before which it was displayed.

Would that Europeans and their descendants in the New World — inspired by their Norse ancestors — could reclaim their courageous ways and pioneer spirit.

Comments are closed.