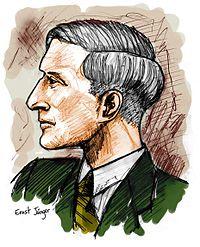

The Conservative Revolution Then and Now: Ernst Jünger

Early in 1927 the Austrian poet Hugo von Hofmannsthal made a famous address to students at the University of Munich. He alluded to and deplored the historical separation in German society between the intellectual and political sphere, between “life” and “mind”. He deplored that German writing in the past had functioned in a vacuum and was “not truly representative nor did it establish a tradition” and was symptomatic of a crisis in civilization which had lost contact with life. In response, he referred to the “legions of seekers” throughout the country who were striving for the reestablishment of faith and tradition and whose aim was not freedom but “allegiance”. He concluded: “The process of which I am speaking is nothing less than a conservative revolution on such a scale as the history of Europe has never known.

Comparing this with the present day situation, when paleoconservative leaders like Paul Gottfried feel lucky to sell a thousand copies of a book, German conservatism was experiencing a period of unparalleled cultural, intellectual, and spiritual vitality as measured by literary engagement. Large numbers of conservative revolutionary political philosophers formed political clubs and organizations and swamped the periodical market with their pamphlets full of semi-political, semi-philosophical jargon. They found access to the “respectable” public, and became the heralds of conservative revolution. They represented an intelligentsia that had the ear of the people, in contrast to the leftist intelligentsia which was considered “Western” and “alien” by most.

Among the most prominent leaders of the “conservative revolution” were Ernst Jünger, Oswald Spengler, and Moeller van den Bruck, each of whom sold hundreds of thousands and in some cases millions of books in Germany and were eagerly followed, debated, and almost canonized. They had succeeded in overcoming the separation between the intellectual and the political. Their writings all place strong emphasis on a homogenous, culturally and spiritually unified nation and on the role of the state in establishing and protecting society. (Jünger’s Über Nationalismus und Judenfrage (On Nationalism and the Jewish Question [1930]), depicted Jews as a threat to German cultural homogeneity; see here.) For this reason they still elicit interest to at least some extent from White nationalists and traditionalists. Although they all rejected the strictly racial theories of National Socialism, this emphasis on a strong, culturally unified state has caused their doctrines and ideologies to be confused with National Socialism. This occurred not only with the left but was characteristic of prominent theorists of the Austrian school like Friedrich Hayek, who are foundational to libertarianism and mainstream conservatism.

This criticism of the conservative revolutionaries is part of the larger criticism of pre-Nazi German society which has been ongoing since the war, and has of course been dominated by the left and such writers as the Frankfurt School’s Erich Fromm and his work Escape from Freedom. According to this line, the failure of German society as reflected in the Third Reich (including the conservative revolutionaries) was that it was insufficiently liberal, that it was insufficiently oriented way from traditional authority and toward modern freedom and rationalism. There is a contrary analysis of some conservative writers like Klemens Von Klemperer (for whom I am indebted to for this piece), alien to the mainstream, that to the extent that German society was deficient, it was more because it was insufficiently conservative, that it lacked sufficient loyalties, roots, allegiances and faith. From a traditionalist point of view that is the only point of view that makes sense, standing as it does against the liberal notion that there was nothing wrong with either Weimar Germany or today’s society that a little, or perhaps a lot, of diversity training and PC conditioning won’t cure. Using this framework it is instructive to see how the conservative revolutionaries, starting with Ernst Jünger, measure up.

Ernst Jünger

Among conservative revolutionary writers Ernst Jünger occupies a unique niche, ideologically and most obviously historically, Jünger lived to the ripe old age of 102, dying in February 1998, just a few months short of the release of Baby One More Time. (Fortunately, by that time the lifelong Nietzschian had converted to Catholicism, thus avoiding the necessity of one last comment on the victory of Spenglerian decadence and the final victory of Zarathustra’s “Last (Wo)Man”.) And it was an active literary lifespan, including definitive works like Eumeswil (1981) and Aladdin’s Problem (1992). After his Weimar period, however, Jünger’s books never attained a mass following. In fact, the works of Jünger’s later life are almost unknown in the English-speaking world. None of the numerous studies I read on the revolutionary conservatives I read ever mentioned that Ernst Jünger was still alive, and that his present work seemed to bear little relationship to the ideas they associated with him.

How do we start in understanding this extraordinarily long and productive life, especially when his work is considered not only in its own right but as paradigmatic of a whole, extraordinarily productive and significant generation of writers? It is certainly not a simple task. Initially one might start with his reputation not in our narrower world. Tom Sunic in part I of his article on Jünger wrote that Ernst Jünger “is today eulogized by all sorts of White nationalists and traditionalists as a leading figure in understanding the endtimes of the West.” Specifically he is of help in charting “new types of dissent and new forms of non-conformist action. Arguably, Jünger could be of help in furnishing some didactic tools for the right choice of non-conformism; or he may provide archetypes of free spirits, which he so well describes in his novels and essays: the rebel, the partisan, the soldier, and the anarchist.” Interpreting such a broad mandate of such a prolific and eclectic writer over such a long life span in such a difficult time as today is not easy.

It might help to reflect briefly on what it is of among all the revolutionary conservatives that makes Ernst Jünger especially popular among some White nationalists and traditionalists. Probably it has much to do with the fact of his life experiences and longevity, spanning the entire twentieth century, as described in Ernst Jünger: A Portrait of an Anarch. Having lived through all these eras, he undoubtedly is a living symbol to some of what a surviving White nationalist in our era would look like. I suspect his popularity might have to do with Jünger’s ability to be “all things to all men.” To WN’s still looking back with nostalgia at the Third Reich, the high position his writings enjoyed and his prominent war service at the Paris high command (even if after the failed plot against Hitler he received a dishonorable discharge) serves him well. To those WN’s and traditionalists of a libertarian bent, the kind that practically canonize Ron Paul, Jünger’s latter day anarchist tendencies (albeit qualified in the form of his term the Anarch) is reassuring.

The free spirits that Sunic describes so well provide the strongest source of continuity in his thought. Other than in this, his early writings in the Weimar period, for which he is mainly known for and studied today by mainstream scholars, diverge greatly from his later writings. Although he is known chiefly for his war works such as Storm of Steel (1925), it was in more theoretical works like Das Arbeiter (1932) that outlined the philosophy of this period. He saw the troubling implications for ethics arising in the modern military and industrial world, but labeled concern for them “romantic.” On freedom, which was of concern to conservatives then as now, he likewise distinguished himself from the other revolutionary conservatives with his easy de facto dismissal of its practical relevance. While rejecting individual freedom as “suspect,” he seized upon “total mobilization” as an ideal situation in which freedom would survive only insofar as it spelled total participation in society. He described an inherently self-contradictory (Hegelian identity) relationship between freedom and obedience: freedom was reduced to “freedom to obey”. While he privately preferred the National Bolsheviks, it is easy to see why the National Socialists were so fond of his early writings.

The later Ernst Jünger

His later writings, starting with On the Marble Cliffs (1939), reflect his disillusionment with National Socialism and his reengagement with ethics and individual freedom. In place of his Das Arbeiter archetypes of “the worker” and “the soldier” (the prototype of the S.S. man), he created a new type, “the woodsman” which is the prototype for the Anarch, defined as “one who strives to preserve by all means his autonomy of thought and his independence in the face of historical trends and the consensus of majorities.” Jünger’s writings returned to the world of the civilian and the individual, to the preservation of freedom against totalitarianism.

At least in this respect, the later Jünger seems to certainly help fulfill Sunic’s search for nonconformist weapons of dissent against today’s multicultural tyranny. The question I have is to what extent, if any, is Jünger’s later thinking representative of or supportive of traditionalism, let alone White nationalism. While he differentiates his Anarch figure from anarchism, it still seems to share certain basic characteristics of anarchistic thought which utterly oppose it to traditionalism or White nationalism. Indeed, Simon Friedrich, an expert on Jünger, characterized Jünger’s position as follows. “ALL external identifications, not excluding racial ones, are ultimately to be separated from”, leading a reader to ask: “So if we have to get rid of our identifications, what are we left with?” Jünger had become a radical individualist.

Jünger was always a consistent thinker. He clearly saw the figure of the Anarch as incompatible with that of the worker or the soldier, the types he saw as logically arising out of his earlier attempts to fashion a vision of a homogenous, unified, and culturally cohesive society. Jünger seems to still have seen a Hegelian identity between freedom and the service and sacrifice any traditionalist or White nationalist vision of society he can envision would have. The fact that the later Jünger switched sides on that issue doesn’t help us with this dilemma. Throughout his life and especially in his later period Jünger always veiled some of the political implications of his views by an ostensible apoliticism. One wonders, if he had chosen to connect anarchistic-tending views toward a congenial, politically oriented outlet, would his ideas have been much different from the political policy prescriptions one sees in Reason magazine or any other of the invariably open-borders libertarian groups?

This is a logical outcome of anarchistic-tending philosophies. Consistent thinkers like Jünger recognize that one cannot have one’s cake and eat it too, and they make the necessary choices. One cannot separate oneself from society by “fleeing into the forest,” as his forest dweller or woodsman (Waldganger) had done, and still remain involved in the struggles and conflicting identities of society. His choice clearly seems to mark him as not one of us, albeit it seems to reflect his characteristic aloofness rather than antagonism to a racial communitarian identity. Imagining his type as just watching from the watchtower, waiting for the right moment to strike, in turn strikes me, as it must have struck those involved in the plot against Hitler who hoped for his assistance, as just wishful thinking. The watchtower metaphor rather brings to mind a quote of his: “I have chosen for myself an elevated position from which I can observe how these creatures (the masses) devour one another”(Der Fragebogen, p. 291). His refusal to involve himself in the Hitler assassination plot was correspondingly another expression of his aloofness “I am convinced … that by political assassination little is changed and above all nothing is helped”(Der Fragebogen, p. 540). One of the ironies of this supreme lover of martial combat is that in politics he was close to a pacifist.

Although the writings of Ernst Jünger should not be seen as infallible truth, I agree with Sunic that he is a potential source of didactic tools for us. I feel a review of some of the other conservative revolutionary writers might be even more useful in this regard. Of all the revolutionary conservatives, Jünger’s writings in many ways are the most problematic. Hence the comment of one of their major periodicals, Deutsches Volkstrum, that “for the conservative man the way of Ernst Jünger would mean a major reorientation.” Other revolutionary conservative writers such as Moeller van den Bruck were also aware of the traditional dilemmas for conservatism, such as the duality between “freedom” and traits such as “allegiance”, “duty”, and “sacrifice.” These thinkers often worked more diligently toward conservative solutions for these dilemmas, typically proposing more complex solutions than Jünger’s streamlined (by ignoring conservative concerns) formulas. As noted above, the conservative critique regarding the weak point of the conservative revolutionary writers is the need to reconcile their ideas with traditional conservative concepts, as exemplified by Jünger. Even if they, unlike Jünger, did not live nearly so far into our present timeframe, their analyses of many things strike one as equally if not more perspicuous.

Will Fredericks is the pen name of an Oklahoma engineer who often posts as “okiereddust” on Internet forums.

Comments are closed.