Valentin Rasputin’s Crusade

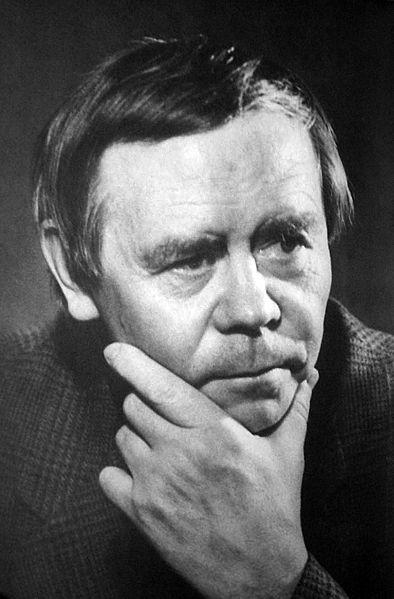

With the passing of the great Solzhenitsyn (1918–2008), the no less great, though in a different genre, Valentin Rasputin (b. 1937), assumed the mantle of doyen of the Russian literary scene. Whereas Solzhenitsyn wrote monumental tomes about festering political issues in Russia (Gulag, Revolution, Jews) and gained international fame thereby, Rasputin, a son and guardian of Siberia, gained his initial recognition mostly from his finely executed, almost precious novellas about life in his homeland and the ruin the Communist government was inflicting on it.

While the differences in style and subject matter between Solzhenitsyn and Rasputin are obvious, the bonds of similarity that immediately identify them as Russian writers are less so. Russian literary figures have religiously followed the tradition of earlier Russian literary figures like Pushkin, Gogol, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, and Bunin in seeing the role of the writer not as an entertainer or propagandist but as a kind of culture-bearer, a teacher, a conscience, and always a patriot — not in the sense of a chauvinist but rather as one who loves his country and its people. Such literary giants therefore help forge “a spiritual commonality” with their readers and give them “moral direction.” To fail to do this would be considered a betrayal of a sacred trust.[1]

The principles of Orthodox Christianity are most evident in the lives of both Solzhenitsyn and Rasputin. Rasputin, for example, was baptized by an Orthodox priest in 1980, when the Communist government was still in power. Both the writings of Solzhenitsyn and Rasputin are suffused with not only a sense of civic responsibility but with an overriding moral concern as well. Just as the Orthodox Church keeps alive and treasures everything in its past history, both Solzhenitsyn and Rasputin reach into older Russian writings to retrieve and reuse words and expressions that might have fallen into disuse. Both writers also studied ancient Russian folklore. Both were literary crusaders.

In their hearts the Russian people still think of their country as Matushka Rus’ “Mother Russia.” All of nature is considered a gift of God. Dr. M. Raphael Johnson described the Russian relationship with nature as natural objects that are pathways to God. Referring specifically to Rasputin, he wrote:

Nature for Rasputin is not merely to be preserved and loved as a mother or wife because of her beauty or because she yields fruit. But it goes deeper. Nature is a mediator of sorts between man and God. … Nature for the sensitive, aesthetic, and ascetic soul contains the fingerprints of God. … For the agrarian; nature, the village, the trees and mountains are friends. They create a home bound together in love.[2]

In a letter to the leaders of the Soviet Union in 1970 Solzhenitsyn too had urged the Soviet leadership to give up imperialism and political “gigantism” and instead turn inward to Russia herself. Consider, he said, the development, protection, and preservation of the Russian northeast — Siberia.[3]

In the period from 1965 to 1985 Rasputin wrote five highly popular belletristic novellas, called “contemporary classics” in Russia, of which Farewell to Matyora was most successful and perhaps closest to the author’s heart in that he was born and spent his childhood on the banks of the Angara River, not far from Lake Baikal, an area that was totally submerged when the Bratsk dam and hydroelectric station were built in the early 1960s. He later wrote:

Our little homeland gives us much more than we can imagine. The nature of our native region is engraved in our souls forever. For example, whenever I experience something akin to prayer, I see myself on the banks of the old Angara River, which no longer exists, alongside my native village of Atalanka, the islands across the way, and the sun setting beyond the opposite bank. In my lifetime I have seen many beautiful things, those made by human hands and those not made by human hands, but I will die with this picture before me, for there is none other so near and dear to me.[4]

And in his final version of Farewell to Matyora in novella form, he used the flooding of the village as a metaphor for Soviet Communism’s drowning of Russia itself, he wrote:

Once more spring had come, one more in the never-ending cycle, but for Matyora this spring would be the last, the last for both the island and the village that bore the same name. Once more, rumbling passionately, the ice broke, piling up mounds on the banks, and the liberated Angara River opened up, stretching out into a mighty sparkling flow. Once more the water gushed boisterously at the island’s upper tip, before cascading down both channels of the riverbed, once more greenery flared on the ground and in the greens the first rains soaked the earth, the swifts and sparrows flew back, and at dusk in the bogs the awakened frogs croaked their love of life. It had all happened many times before.[5]

This passage from one of his most popular novellas describes the nostalgia, homesickness, and natural opposition to modern “progress” that haunt most of his early work. However, it would be wrong to think that the village writers opposed all modernization. They simply wanted all major industrial projects to be compatible with and considerate of the ecology.

In 1985 in his novella Fire he made the fire in a Siberian camp a prophetic judgment on the entire Soviet system. And when in the late 1980s Soviet planners were seriously considering reversing the flow of Siberian rivers, Rasputin, then a member of the Congress of Peoples Deputies, warned that if that was even tried, the Russian nation might consider seceding from the Soviet Union. He wrote:

When reflecting on the actions of today’s “river-rerouting” father figures [the modernizers], who are destroying our sacred national treasures up hill and down, with the haste of an invading army, you involuntarily turn to this experience: it would not be a bad idea for them to know that not everything is forgiven at the time of death.[6]

Rasputin also belongs to a literary group, known as the “village prose writers,” which, influenced by the teachings of the nationalist group Pamyat [the People’s National-Patriotic Orthodox Christian Movement] and revolted by the desolation increasingly seen in the Russian countryside because of reckless modernization projects, used their literary skills in an attempt to stop the despoliation of Russian lands. The Pamyat group maintained that Jews have dominated the Soviet government from the beginning—at the time the farms were collectivized and famine ensued, and later under Boris Yeltsin when Zionists and Freemasons were actively working to subordinate the government to Jewish capital. As rootless cosmopolitans the Jews, Pamyat held, had no sympathy whatsoever for the Russian people, and no understanding of or concern for country life, agriculture, or nature in general.

They, the Jewish usurpers, were of course not ethnic Russians. They are individuals whose political allegiance and faith differ from that of the native population and who, despite that, sought to usurp moral authority in Russia. By virtue of birth and philosophy Rasputin and his colleagues are Slavophiles not Westernizers, intelligent and gifted rural volk, not urbanites; agrarians, not city planners. And they are devoted to alleviating agrarian conditions. Repelled by destructive government policies, they fight to preserve and protect the beauty and fruitfulness of the Russian landscape. It was inevitable that sooner or later they would identify Jews and/or Zionists as the rootless urbanites responsible for the destruction. In a signed letter to President Yeltsin, the president of the Russian Federation, the head of Pamyat, D. Vasilyev, wrote:

Your Jewish entourage . . . has already made good use of you and don’t need you anymore. . . .The aim of international Zionism is to seize power worldwide. For this reason Zionists combat the national and religious traditions of other nations and to this end they devised the Freemasonic concept of cosmopolitanism, working to subordinate the government to Jewish capital.[7]

The gifted author Aleksandr Prokhanov wrote the wildly popular roman-à-clef Mr. Hexogen that mocked Yeltsin, his family, and business associates — a select group of former communists who almost overnight became the Jewish oligarchs. The Soviet authorities have never even attempted to silence Prokhanov, Rasputin or the other village prose writers because they knew the Russian people would support the complaining writers over the government.

The village writers and other critics of the government subsequently broadened their attacks. They not only blamed the Jews and/or Zionists for the immediate chaos but also for having destroyed Russian village life, the backbone of the country, for having turned Russia into a secular country by murdering the Orthodox clergy and converting the churches into movie theaters, warehouses and worse during and after the Communist Revolution, and for having enriched themselves in the process.

The moral relativism of the West, too, had always appalled Rasputin. In 1991, for instance, he not only did not object when governmental authorities tried to put Moscow’s gay newspaper, Tuma, out of business, but also approved of it. Rasputin commented:

If you allow one thing, it can lead to something else. If you legalize homosexuality, the necrophiliacs will clamor for their rights—after all they’re a sexual minority too. When it comes to homosexuality, let’s keep Russia clean. We have our own traditions. That kind of contact between men is a foreign import. Three years ago we came out against beauty contests. They seemed outrageous then, but compared with this, they were purity itself. To get rid of censorship would mean getting rid of morality. You either have morality or you don’t. We must take radical steps to preserve a moral society.[8]

In 1985 when the Soviet Union was already experiencing its early death pangs, Rasputin abruptly abandoned belles lettres and his novellas, and for the next twenty years turned exclusively to nonfiction prose advocating in plain text what his novellas had previously expressed in poetic language, most specifically, his opposition to the despoliation of the homeland. The earliest such nonfiction work, called Siberia, Siberia, the first of several planned volumes on the ethnohistory of Siberia, appeared in 1991.

So popular had Rasputin’s writings become that in 1990 Mikhail Gorbachev asked him to serve on the Presidential Council to assist him with his reform agenda. Among other causes, Rasputin advocated for a ban on further industrial pollution of Lake Baikal, for the complete separation of Church and State, the cessation of irreligious and atheistic talk on the part of the government, and a halt to the ruthless exploitation of Siberia’s mineral wealth. He had responded to Gorbachev’s invitation with enthusiasm and high hopes, believing that perestroika was the best hope for a better future. It was during this period that the Siberian writer witnessed firsthand the disintegration of the Communist regime and its replacement by the new incoming elite — the oligarchs.

On June 22, 1991, the anniversary of the day Germany attacked the USSR, the new president, Boris Yeltsin, frightened by the widespread discontent and anger among the Russian people caused by the chaos and poverty during the transition period from Communism to a capitalist market, warned against what he termed fascistic and anti-Semitic elements in the Russian people alluding to Rasputin and like-thinkers.

In an important interview given to the Sovetskaya Gazeta newspaper the outraged Rasputin responded angrily, saying:

It appears that for President Yeltsin the threat of “Russian Fascism” has exceeded all boundaries and poses the prime threat to Russia, whereas I, the writer Rasputin, am convinced that no such thing as Russian fascism exists. Yeltsin was instructed what to say and he parroted it. And the instructors sacrilegiously chose 22 June, the day Hitlerite Germany attacked the Soviet Union, to commit an outrage even against the victims of the war in which millions gave their lives in the struggle against fascism. The people who actually defeated fascism are now being presented as such a monster…

When Russians have been unjstly accused of anti-Semitism, the slanderers are very likely Russophobes, which in this case were certain Jews who cleverly worked to transfer their own unfounded animosity toward the Russians by blaming them for an irrational and unjustified dislike of Jews. …The responsibility for today’s undeclared war is being shifted onto us Russians. The plundered people who have been reduced to beggary, slandered, and have made enormous sacrifices—they are to blame. …

Generally speaking, when one is wrongly labeled a fascist or an anti-Semite by foreign critics, it can be tolerated because the accuser may have been incorrectly informed. But when your own government, panicked by the discontent provoked by its own stupid policies, accuses unnamed citizens of being anti-Semites, fascists and provocateurs, then native patriots must speak out. …

If you are a Russian, and if, God forbid, you are concerned about the interests of your own unfortunate people— you are an anti-Semite. If you call a Jew a Jew, you immediately become an anti-Semite for just having uttered the word “Jew,” because uttering it implies you have reflected upon it. If you dislike the endless sex and violence on television, you are an anti-Semite—after all, television is in Jewish hands. If you have screwed your face in disgust over a page of Moskovskiy Komsomolets [a daily newspaper, literally “Moscow Member of the Young Communist League”], which pursues its mockery of your people’s sacred relics, you are an inveterate anti-Semite. … This is how in the media I became referred to as a world famous anti-Semite not a world-famous writer. . . . We would never accept—be it in our own people or in any other people—the principle of being “chosen” or “über alles,” the right to impose one people’s will and taste on others, the expectation of the world’s special gratitude for just being there. … There are the chosen people and there are the other peoples—the goyim—who can be ignored…

It is difficult to imagine that the genocide of Jews during World War II could be forgotten or underestimated. But genocide, just like any other historical event, is invariably the product of a certain number, in this case especially inflated, of individual responsibilities, and of historical context. There is an implied belief that the genocide of the Jews is something more than an historical fact, that it is the collective guilt of several nations and several religious cultures. Yet this very concept of collective guilt conceals one of the most pernicious ingredients of any racist phenomenon. … It emerges that the Jews have turned their national disaster into business.

When asked by the interviewer how he could tolerate the slander directed at him, he responded:

That is nothing. Frontline reality tempers you. Seneca said that being disliked by fools is something laudable. . . . Paradoxically, the danger of the emergence of real anti-Semitism lies in the passionate desire of intolerant Jewry to confiscate history.[9]

In the same interview Rasputin notes that he suspected his prominent position in the Presidential Council might have annoyed some outsiders and that perhaps they might be inclined to attempt to discredit him. He then singled out journalist Bill Keller of The New York Times for misrepresenting his views:

When Keller’s article was translated for me, it emerged that on the most contentious issues, when I had said ‘yea’ it appeared as ‘no’ and whenever I said ‘no’ it appeared as ‘yes’. When I asked the journalist for the recording of our conversation, he showed me one of the cassettes, the other ‘could not be found’. But even the one was sufficient to take him to task. What happened? Mr. Keller vanished…

Commenting on the disintegration of the Soviet Union, Rasputin noted:

When the noise finally settled down and the smoke had cleared, the former State was no longer in existence and the world was presented with the images of Berezovsky, Gusinsky, Smolensky, Chubais, Nemtsov and others who had seized power. … The most hated images in Russia, with whom the plunder of the country is associated. They should have been put away somewhere at least for a while, so as not to have them provoke the people! I could cite a multitude of cynical revelations about that victory, as well as instances of arrogance and scorn for our people. Who should be afraid of whom? Is it not right that, whenever there are cries of anti-Semitism, we should be looking for Russophobia, for a striving for final victory to make sure that not a squeak is heard from us?

Only when Vladimir Putin and his team achieved power did the Russian people finally find some relief, understanding, and support from their government. Economic conditions improved. Jewish oligarchs who took it upon themselves to criticize and interfere with the Putin government were restrained and Jewish control over the mass media, especially television, was reduced.

Then in 2005 a new bombshell exploded in the form of “Letter 500”, an open appeal to the Soviet Chief Procurator to investigate and bring charges against certain Jewish national and religious organizations was signed by 20 deputies of the Duma and some 500 other prominent Russians, including the editors of Orthodox Christian, Russian nationalist, and Communist publications. First published in the Rus’ Pravoslavnaya (Orthodox Russia) newspaper and displayed on its website, it accused Jewish organizations of fascistic behavior, incitement of the Russian people, propagating and promoting Talmudic teachings, and demanded that such Russophobic behavior be banned as extremist. In effect, this action turned tables on the Jews by accusing them, and not the Russian people, of fascistic behavior and instigating domestic warfare.

Following is the Introduction to the appeal:

Russophobia in Action

Jewish Happiness, Russian Tears

Representatives of the Russian public demand that the Procurator General of the Russian Federation stop the unrestricted spread of Jewish ethnic and religious extremism.

Esteemed Procurator General!

On 18 December 2003 during a television address to the people, the President of the Russian Federation, V. V. Putin, cited the following figures: in 1999 with reference to Statute 282 of the Criminal Code concerning “incitement to national discord, four individuals were indicted, in 2000 the number was 10, and in 2003 “more than 60 cases of incitement were recorded of which 20 went to adjudication. About 17–20 guilty verdicts were returned.” (V. Putin: “Conversation with Russia.” 18 December 2003, Moscow, 2003, p. 53)

Who Is Shouting “Catch the Perpetrator”?

Jewish activists or organizations initiate the overwhelming majority of these cases that routinely accuse the defendant of anti-Semitism, while the overwhelming majority of the accused and indicted refer to themselves as Russian patriots. Now, the well-known, independent politician and publicist, the former head of the State Publishing Committee, B. S. Mironov, finds himself among the accused.

We acknowledge that the comments addressed to Jewry by the Russian patriots are often of a negative nature, excessively emotional, unacceptable in public discourse, and which the courts hold to be extremism. However, not once in the judicial proceedings noted above was the reason for their sharpness or the primary source of their extremism in this interethnic conflict examined.

The main question that the trial and the court ought to address is whether or not the negative judgments the Russian patriots make of Jewry are true in point of fact. If they are not true, then this is truly a matter of the degradation of Jews and incitement of religious and ethnic discord. If they are true, then their opinions are justified and, regardless of the emotionalism involved, they cannot qualify as degrading, inciting discord, and the like. (For example, to call an honest man a criminal is degrading to the individual, but to call a criminal a criminal is a true statement of fact.)

Moreover, inasmuch as there are two sides (accuser and accused) in this interethnic conflict, it must be determined which of the sides initiated the conflict and is therefore responsible for it, and whether the actions of the accused are not actually self-defense against the aggressive actions of the accusing side?

We implore you, Procurator General, to consult the large number of generally recognized facts and sources with respect to these questions on the basis of which an incontestable conclusion can be drawn, namely, that the negative opinions held by Russian patriots of characteristics typical of Jewry and their actions against non-Jews are true, wherein these actions are not random but are prescribed in Judaism and which have been practiced two thousand years.

Thus, the opinions and publications incriminating the patriots fall under the rubric of self-defense, which, while not always stylistically correct, are justified in essence. …[10]

Media and Israeli reaction to the appeal was as expected. Among others, The Baltimore Sun: “Russian Jews Say Nationalists Rekindle Anti-Semitism”; UK Telegraph: “Outrage in Russia”; BBC: “Anti-Semitism Alarms Russian Jews”; Israel Shamir – “Bloodcurdling Libel”; The Israeli Ambassador: “The Letter is a Bloody Slander.”

The Office of the Procurator made a Solomonic decision. After making clear that the content of the Letter in no way represented the official views of the Russian government, it decided that since the appeal has been properly submitted through official channels and with due respect to the officials involved, it could not be considered criminal. However, it chose not to press charges against the Jewish organizations named.

While there is no evidence that Rasputin himself was involved in this affair, the plaintiffs may well have been influenced by the author’s sentiments. The people made their opinion of the Appeal manifestly clear by resubmitting it somewhat later with 5,000 signatures, still later with 15,000 signatures, and by 2008 with 25,000 signatures.

Rasputin then chastised the Jews for their role in the Communist Revolution.

I think that today the Jews should feel responsible for the sin of having carried out the revolution and the subsequent terror—the terror that took place during and especially after the revolution. They played a large role and their guilt is great. Not for killing God, but for that. They perpetrated the relentless campaign against the peasant class whose land was brutally expropriated by the state and who themselves were ruthlessly murdered.[11]

It must be said, even emphasized, that Rasputin himself had never been a member of the Pamyat group or an anti-Semite until he abandoned his creative writing to participate in the Government as a public affairs writer, first under Gorbachev and then Yeltsin during the transitional period. During that period he was made aware first-hand of the power struggle and the attendant criticism of the activities of the Jews. After all, his predecessor Solzhenitsyn wrote two volumes on that question. However, after Rasputin returned to Irkutsk, the Jewish question vanished from his writing.

After twenty years in the frontline of domestic disputes, Valentin Rasputin returned to his long-time residence in Irkutsk, where today he maintains close contact mostly with agencies of the Orthodox Church — the Patriarchal Council on Culture, the newspaper Literary Irkutsk, the literary journal Sibir and other such local regional institutions. On the occasion of his 75th birthday (March 15, 2012) and the public celebrations honoring him, Rasputin expressed his disappointment in the time spent in Moscow as a crusader for reform:

My foray to the seat of government amounted to nothing. It was completely in vain. My optimistic presentiment had deceived me. I am embarrassed to recall why I went there. I thought that there were years of struggle ahead, but it turned out that the collapse was only a matter of months. I was treated like an unpaid extra that was not even allowed to speak.

Then the still undaunted crusader, who abandoned his muse in those twenty years for political polemics, announced the publication of his new book, appropriately entitled Those Twenty Murderous Years.

End Notes:

[1] Margaret Winchell and Gerald Mikkelson. Siberia, Siberia. Northwestern University Press, Evanston, IL, 1991, pp. 1-21

[2] Matthew Raphael Johnson. The Social Vision of Valentin Rasputin. www.slavija.proboards.com/index.cgi?board=general&action=display&thread=4766

[3] Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Letter to the Soviet Leaders. Harper & Row, New York, 1975, p. 55

[4] Winchell, Mikkelson, op. cit., p. 13

[5] http://wikipedia.org/wiki/Valentin_Rasputin

[6] James H. Billington. Russia in Search of Itself. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland, 2004, p. 39

[7] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pamyat

[8] Lionel Joyce. What Rasputin Said. The New York Review of Books, April 11, 1991

[9] Valentin Rasputin and Viktor Kozhemyako (Interview). Sovetskaya Rossiya. January 5, 1999, p. 2.

http://www.cdi.org/Russia/Johnson/3010

[10] The complete text of this document has been made available by several sources, including The Barnes Review, No. 3, 2005, pp. 50-57

[11] Maxim D. Shrayer. Anti-Semitism and the Decline of Russian Village Prose. Partisan Review, Vol. LXVII, No. 3, 2000

Comments are closed.