Look Who’s Coming to Brussels: Analysis of the Nationalist Victories in the EU Elections

Editor’s note: Comments are open for this article.

The leaders of the European Alliance for Freedom, the biggest coalition of nationalist parties in Europe. From left to right: Matteo Salvini (Italy), Harald Vilimsky (Austria), Marine Le Pen (France), Geert Wilders (Netherlands) and Gerolf Annemans (Flanders, Belgium).

Prior to last week’s European elections, a French Socialist commented that a nationalist victory would spark “planetary astonishment.” And certainly there has been a great deal of chattering by the chattering classes as to the implications of so many anti-establishment parties finishing first in their respective countries across Europe and, in particular, the election of over 100 nationalist and another 100 soft-euroskeptic representatives to the European Parliament.

But how do we interpret these results? In particular, what do they mean for nationalists? So far, besides an excellent discussion of the elections on American Renaissance, the event appears to have been little-analyzed by American nationalists.

Madeleine Albright once said that “To understand Europe you have to be a genius … or French.” In fact, this is far too generous to the French. I can vouch that no one in Europe or anywhere else really understands the European Union. And, because of Europe’s marvelous diversity, it is difficult to generalize about the nationalist vote in the 28 different countries. Each nation follows its own socio-political rhythm and has its own particular values. Every commentator inevitably generalizes about Europe from the skewed national perspective he knows best.

With those two caveats, I will do my best to draw out the implications of this remarkable vote.

(As an aside, for Anglo-Saxons trying to grasp the meaning of day-to-day EU news, one could do worse than to follow soft-euroskeptic think-tank Open Europe, which is very informative as long as one bears in mind their particular British/business/Atlanticist orientation.)

Who was elected?

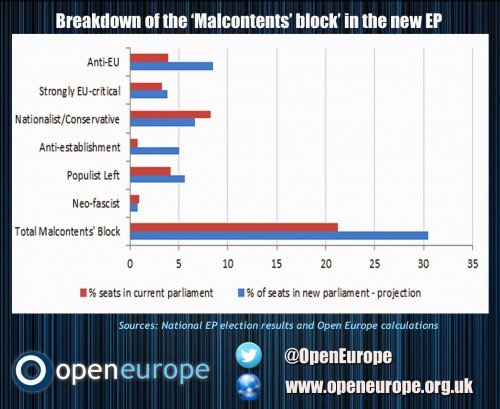

The EU-level elections are considered secondary elections in which voters are more likely to ignore or to use to “punish” mainstream parties. And punish they did, with a massive increase in the vote for populist anti-establishment parties who now make up one third of Members of the European Parliament (MEPs), up from about a fifth in the last elections in 2009. Turnout was typically low at 43.1%, including staggeringly low figures in much of post-communist Central Europe (evidently, despite lip service, not particularly enamored with “EU democracy”), with a mere 19.5% in the Czech Republic and 13% in Slovakia.

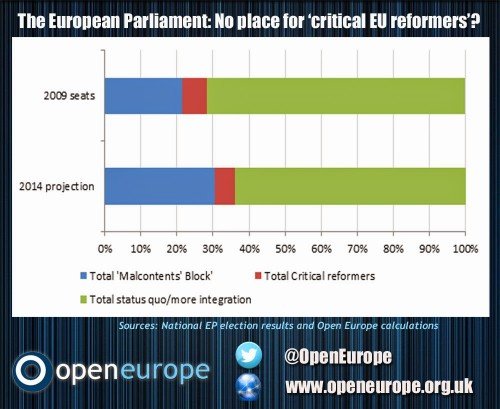

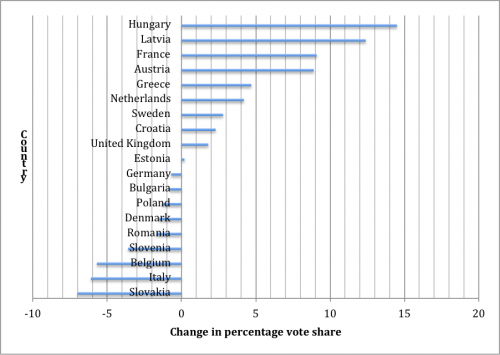

The different populists’ progress is visualized in these graphs by moderate euroskeptic think-tank Open Europe:

The elections are then a significant measure of public discontent. But the protest voters are divided on “what is to be done.” The newly-elected rebels are a highly heterogeneous group including nationalists (UKIP and the National Front being first in UK/France respectively), leftists (Syriza being first in Greece) and more-difficult-to-classify populists (including the moderate euroskeptic, sometimes anti-immigration Five-Star Movement (M5S) led by comedian Beppe Grillo coming in second in Italy).

Interestingly, there has been a first flicker of the open return of German nationalism with the moderate euroskeptic, anti-euro and immigration-critical Alternative for Germany getting 7% of the vote and even the third positionist National Democratic Party getting its first MEP.

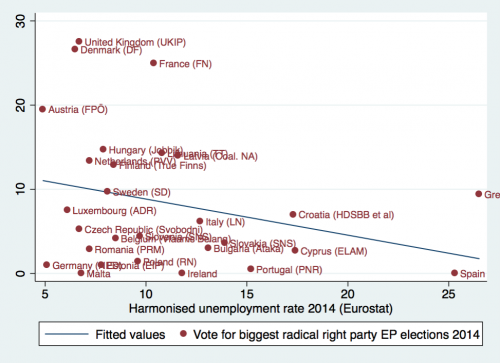

There was no national-level correlation between economic despair and the nationalist vote. Nationalists, broadly-defined, got 10-30% of the vote in prosperous Denmark, Sweden and Austria, as well as in by-no-means-impoverished Britain and France. Apparently, it’s not the economy, stupid.

Lack of correlation between unemployment and the nationalist vote.

In some countries nationalists did poorly. Geert Wilders’ Party for Freedom did not gain any seats in the Netherlands, the regionalist Northern League’s vote was halved in Italy, and Bulgaria’s Attack lost its two seats (all these parties were perhaps tainted by stints supporting/participating in government). It appears the nationalist vote has tended to bleed into more “respectable” parties (e.g. the British National Party’s loss of two MEP with UKIP’s triumph, Belgium’s Flemish Interest losing all but one MEP in the face of an increase in more mainstream Flemish nationalists). In countries like Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece the majority of the protest vote went to leftist or iconoclastic populists.

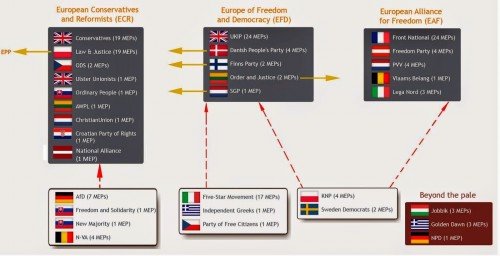

If the populists are divided, the nationalists are too. They disagree along certain policy lines and their degree of political incorrectness. Euroskeptics are divided into the following four broad groups according to their extent of political incorrectness:

- EU-critical: Pro-EU, anti-federalist, typically anti-euro. These parties are led by the British Conservatives but also include the softer nationalists like the New Flemish Alliance (N-VA the most popular party in Flemish-speaking Belgium), the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and Poland’s Law and Justice (PiS).

- Anti-EU: The core of this group is UKIP. Other parties gravitate around it in a rather unstable way: If they are soft, why not have more influence by joining the British Conservatives? If they are hard, why not join the French Nationalists?

- Anti-Islamization: France’s National Front (FN), Austria’s Freedom Party (FPÖ), Italy’s Northern League (LN), Belgium’s Flemish Interest (VB), the Netherlands’ Party for Freedom (PVV), and possibly others.

- Anti-Zionist: Hungary’s Jobbik, Greece’s Golden Dawn, Bulgaria’s Attack and Germany’s National Democratic Party (NPD).

Possible EU-level euroskeptic alliances (as of May 2014). (See original here.)

Each of these markers represents a step in a rising crescendo of political incorrectness and rejection by the Establishment. Unfortunately, nationalist parties themselves, necessarily or not, validate political correctness’ “guilt by association” strategy by distancing themselves from each other, so as to be more allowed to participate in the politico-media system. UKIP rejects the FN, while the FN rejects the anti-Zionist “untouchables” (even if, in the case of Jobbik, we are talking about a party supported by about a fifth of a country). Thus they are divided and ruled.

Interestingly the British and French politico-media establishments have shepherded UKIP and the FN into similar positions. Both are rejected by the mainstream parties who reject all electoral cooperation or coalition governments (such cooperation is typically acceptable for hard-leftist parties including Communists), both continue to be demonized as “racist” and, in the case of the FN, “fascist” by the media, but both at the same time have enjoyed very respectable media access.

It’s hard to tell what the systemic logic here is: Are Western media-political systems tolerant of nationalist parties so long as they stick to a strict civic nationalism and make no mention of the Jewish question (the sins of Nick Griffin, Marine Le Pen’s father Jean-Marie)? Is it acceptable to promote UKIP and the FN as natural “pressure valves” to release popular discontent so long as they are politically ghettoized with a sterilized 20-30% of the vote? Or are the French and British elites considering a return to the Nation-State, via UKIP or the FN, as an acceptable possibility that they should prepare for? It is difficult to say.

UKIP will probably lead a very heterogeneous group of anti-establishment parties united by little. France dominates with 24 MEPs, a more coherent group of bone fide nationalists. The French, Dutch, Italian, Austrian and Flemish (Belgium) nationalists have already pledged to form a group at a recent press conference in Brussels (video with English interpretation).

In general, European nationalist parties (including implicitly and sometimes explicitly the more “respectable” ones, like UKIP) agree in being euroskeptic, anti-immigration and anti-Islamization. They tend to be pro-Russia, including, perhaps surprisingly, in parts of Central Europe historically oppressed by Russians (e.g. Hungarian, Bulgarian and even some Polish nationalists). They also tend to be broadly antiwar, although there are many who adhere to neoconservatism/Zionism.

Beyond that, there are many differences among European nationalists. Regionalist-nationalists like the Northern League and Flemish Interest are not against the EU as such. Northern nationalists such as UKIP and the Dutch Party for Freedom tend to be “neoliberal” and support free trade, while French nationalists are typically protectionist.

The policy differences are largely irrelevant however because that’s the point of euroskeptic self-government: Everyone gets to run their own country as they wish instead of getting into disputes as to how one’s neighbor’s country should be run.

The Impact of the Elections

About 110 full-blown nationalist MEPs will sit in the assembly — about one seventh of all members. Their direct significance to EU-level politics will be limited. As indicated above, two-thirds of MEPs will remain mainstream. As EU Commissioner and European “federalist” Viviane Reding has pointed out, the nationalist vote will be ignored and the so-called “center-left” and “center-right” parties will govern together in a sort of “Grand Coalition” coalescing around the same agenda of economic “post-democratization” (e.g. bringing macroeconomic policy under technocratic control), neoliberalism, multiculturalism and the slow abolition of Europe’s Nation-States.

In any case, the European Parliament’s influence is limited anyway. It did get some teeth in 2010, with real powers to reject, amend or pass legislation particularly on market regulation related to consumers, the environment or finance. On these issues, the assembly has become something of a genuine “lower house” for the EU regime, co-legislating as an equal on many topics with the Council of Ministers, a kind of a senate where the 28 national governments are represented.

The EU parliament has basically no powers on foreign policy, labor/welfare policy or macroeconomic policy, but MEPs love to grandstand on those topics. They have some limited say on immigration but the chaotic EU rules in that area are more the product of the typically waffling consensus of national governments.

Nationalists can then be expected to have little direct impact at EU level. Nevertheless, these nationalists and other populists could potentially block further EU integration and policies where the centrist majority is divided, especially on controversial topics such as the EU-U.S. free trade agreement currently being negotiated (known as “TTIP”). In addition, about 100 mainstream MEPs are EU-critical, which could also make integrationist lawmaking more difficult.

The real benefit of having nationalist MEPs is in terms of influencing public discussion and a stronger hand in national politics. The symbolic impact of UKIP finishing first in Britain and the National Front first in France in discrediting the mainstream parties and building confidence towards winning in national elections may prove decisive.

Each MEP will receive the equivalent of about $8,500 per month in salary, $5,850 per month in expense allowance, up to $28,800 per month for staff, and $40,000 per month for EU-level political activities. In short, every MEP means almost $1 million annually for his political cause. As a result of these elections, the EU will be directly subsidizing the nationalist cause in Europe to the tune of $110 million per year, a fact whose irony is not lost on Eurocrats and mainstream politicians, particularly significant given nationalists’ frequent difficulties in fundraising.

In addition, nationalists will have highly visible bully pulpits in the European Parliament from which to criticize the euro-globalist project. It matters not that the assembly is typically largely empty: The hyperbolic invectives of a Nigel Farage (his attack on EU Council President Herman Van Rompuy remains legendary) or a Daniel Hannan (calling Gordon Brown “the devalued prime minister”) are eagerly picked up by mass media and shared on social media. Marine Le Pen of the National Front in particular will, as the likely leader of a new nationalist EU-level group in Parliament, earn the right to directly harangue the top EU officials and national leaders whenever they address the chamber.

Nationalists, even if they don’t come to power, will at least incentivize mainstream parties, fearing electoral annihilation, to adopt patriotic policies such as limiting immigration or revising the EU’s rules mandating free movement of people. UKIP pressure has been decisive in getting British Prime Minister David Cameron to pledge to an in-out referendum on EU membership. Just before the EU elections, former French president Nicolas Sarkozy came out of the woodwork to call for a “Schengen II” limiting free movement of people only to rich countries, and Italy has made increasing noises about the unmanageability of the waves of African immigrants coming to Lampedusa. Just after the elections, the Socialist French government abandoned a longstanding proposal to grant immigrants the right to vote in local elections.

The placation of nationalist sentiment with merely cosmetic measures is likely to continue however — the UK and Germany have adopted measures against “welfare tourism” by EU immigrants — whereas in fact EU immigrants, unlike non-EU immigrants, tend to contribute positively to national coffers and in most cases pose no real challenge in terms of medium-term assimilation. Political correctness has perversely incentivized nationalists, in their pursuit of “respectability,” to make no distinctions in their opposition to immigration, treating a blue-collar Pole as equally difficult to pay for and assimilate as a Somali refugee. An excellent case of how political correctness undermines European solidarity and common sense policies.

The EU electoral campaign, such as it has existed, focused on macroeconomic issues and foreign policy, two areas where the European Parliament is basically irrelevant. Ironically, the parliament does have some powers over immigration: if there were agreement with the EU bureaucracy (the Commission) and national governments, an EU-level anti-immigration policy, complementing but not replacing national policies, would be conceivable. Legal admission levels however remain a sole decision of national governments but the Schengen Area of borderless free movement, which includes most EU countries and makes border checks between members the exception not the rule, in practice makes it difficult to fight illegal immigration.

In any case, mainstream EU politicians have shown little interest in legislating on immigration, apart from lamenting the deaths of illegal immigrants in the Mediterranean. Even the center-right “Christian-Democratic” candidate for the EU Commission presidency, Jean-Claude Juncker, proposed an increase in legal immigration to supposedly prevent such tragedies and to address EU countries’ shrinking workforces. One wonders how seriously these people believe displacing their current workers with largely non-assimilable Afro-Muslims is even sustainable economically, let alone sustainable socio-politically.

Future Prospects in Europe

Gains and losses of European nationalist parties, 2005-2013.

One is tempted to quote Alain Soral on the FN’s frequently decent 10–20% of the vote electoral performance in France: “It’s promising. But how long have we been promised?”

According to polls, Western Europeans tend to rate the economy (especially jobs/distributional issues) and immigration as their two top issues — topics over which the EU parliament’s say varies from limited to non-existent. This may partly account for the cripplingly low turnout to European elections. With around 40% turnout in most countries, this means that even where nationalists received 25% of the vote victory was based on only one in ten potential voters. Politics is of course always the work of organized and motivated minorities. But still, it puts things in perspective.

Active support for mainstream parties is collapsing is most of Europe. But in general, firm, depoliticized majorities remain afraid of potential nationalist governments. Indeed, in Italy the impotent Socialist government won an incredible 40% of the vote, representing the “responsible” centrist majority which was opposed to either Grillo’s populism, nationalism or a center-right discredited by former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi’s antics. This apathetic, conservative, effete, fearful majority is likely to be awakened from its dull slumber whenever nationalists seem close to their goals.

Nationalists also know that electoral fortunes rise and fall. Most of these nationalist parties have been around for a long time.

Nonetheless, these results are indeed significant and promising. Among French voters, the FN won 43% of blue-collar workers, 37% of the unemployed and 30% of people under 35 — by far the leading party in each category.

The first-place win of the FN and UKIP may contribute to breaking the taboo against them as possible governing parties. Success breeds success. Voters who may have felt inhibited to vote for nationalist parties because of media-created guilt will perhaps become less inhibited as the nationalists become more mainstream. Because of the increasing popularity of nationalist parties, people who openly identify with them will not be as shamed or stigmatized.

Further, because their success has increased funding, nationalists will have greater resources to make their case and influence the discussion. Mainstream parties are likely to adopt real or simulated nationalist policies to forestall electoral defeat.

The broader context is also favorable to new ideas. A recent Pew poll found that majorities of Europeans in most countries believed immigrants were “not assimilating,” that immigration should be stable or reduced, and that immigrants were an economic burden, and they had “unfavorable” views of the Roma. (Incidentally, an incredible 47% of Greeks said they had an “unfavorable” view of Jews, as against 26% of Poles, 24% of Italians and less in other countries.) Minds are likely to become more focused on the alarming consequences of what the French call le Grand Remplacement (“the Great Displacement”).

In addition, the fruits of the EU’s combination of neoliberal borderlessness and one-size-fits-all economic policies mean that economic recovery, if it exists at all, will be lackluster at best. Economic-financial collapse of the eurozone and of Western bankster institutions remains a possibility. Race relations are likely to worsen in many countries. The nationalist case can only become more convincing in such circumstances.

Finally, it is worth mentioning the case of Hungary, which arguably already has the EU’s only conservative-nationalist government. The ruling party Fidesz won an incredible 51.5% of the vote in the EU elections while hard-nationalist Jobbik (which is regarded as anti-Semitic by Jewish organizations) finished second with 14.7%. Prime Minister Viktor Orbán is by no means a radical and his party still sits with the mainstream center-right at EU level, but from the tone of foreign media and EU politicians, you’d think he’d invaded the Rhineland. Yet, about a fifth of Hungarian voters (Jobbik got 20.3% in recent national elections) think Orbán isn’t nationalist enough. Given that Orbán has been in power since 2010, this is an encouraging sign for the enduring popularity of nationalism once nationalist governments come to power.

In short, this is for nationalists a promising victory in what will be a long war.

Comments are closed.