The History of the League of Empire Loyalists and Candour

The History of the League of Empire Loyalists and Candour

The History of the League of Empire Loyalists and Candour

by Hugh McNeile and Rob Black

Published by the A.K. Chesterton Trust; 150 pages

One of the most remarkable aspects of the collapse of the British Empire was the relative lack of people who seemed to care about it. Resistance to the process was extremely muted, both from the Empire’s elites and the mass of its people. This was baffling considering its two-hundred-year stretch of global dominance, its enormous impact, and the millions of people around the world whose interests were directly tied to its existence.

The sheer inexplicableness of the event tends to throw up either glib and dismissive explanations, or dark and dastardly ones that seem more like paranoid conspiracy theories. In short, either the Empire was done to death by secret cabals and nefarious networks or it was simply on the wrong side of history — and accepted that fact with an all-too-easy grace and sense of resignation.

Today it is difficult to get a sense of what really happened. Mainstream history, of course, has its narratives worked out — Britain was exhausted after its war with Germany and Japan, attitudes to race had been transformed, and the “Winds of Change” blew in shortly afterwards followed by the “Winds of Multiculturalism.” Thanks to the alternative history now possible due to the internet, this narrative now faces some opposition, but because the period is rather remote, such opposition usually comes from those with a particular axe of their own to grind.

A better way to get at the truth is to focus on those few who were most concerned about the demise of the British Empire, and to consider their experiences. In this respect one of the best books is Hugh McNeile and Rob Black’s The History of the League of Empire Loyalists and Candour, published last year.

The core of the text was written in the 1980s by McNeile (thought to be the pen name of the late Dr. Kevan Bleach). It has recently been edited, augmented, and updated by Rob Black of Candour and the A.K. Chesterton Trust. Candour was the journal edited by A.K. Chesterton that served as the mouthpiece of the League of Empire Loyalists from its foundation in 1954 until its merger into the National Front in 1967.

Chesterton looms large throughout the book and was the guiding spirit of the movement. A nephew of the famous writer and man of letters G.K. Chesterton, he was briefly a member of Mosley’s British Union of Fascists and also served in both world wars, each time in Africa, where he was also born.

He inevitably comes across as one of those stiff-upper-lip, ramrod-for-a-backbone types who made the British Empire such an enduring and efficient organization in its days of glory. But he also had his artistic and humorous sides, writing poetic prose, a comedic novel (Juma the Great), and at least one excellent play (Leopard Valley). But it was his uprightness and integrity that were at the heart of the man.

For this reason he is a clear prism. The forces acting on him are never dissipated in murky doubts, self-interest, fear, or confusion, but thrown into sharp relief by his always upstanding response to them. At times this gives him the aura of a hero from a Greek tragedy as we see him reacting to the forces of dissolution and pursuing, without compromise, his own self-realization and political destiny.

The first chapter “Beginnings” details how A.K. was set on his path. He was then working for a magazine called “Truth”:

It specialized in a particular brand of vigorous, independent journalism that possessed a John Bull quality in its proclamation of the virtues and values of the British Empire. The Manchester Guardian once described it as being ‘almost the last remaining home of the declining art of invective.’ A polemical writer of A.K.’s calibre could not have felt out of place on its staff with his talents in that field! (p. 13)

But made to feel “out of place” he soon was, in accord with the new post-patriotic culture of the post-war period:

A particularly objectionable effort was made shortly after he joined Truth to have A.K. removed. A deputation of Jews called on Collin Brooks, the journal’s editor, with the very strong suggestion that he should dismiss A.K. from his service. (p. 14)

This move, motivated by his previous link with Mosley’s party, was unsuccessful, but in 1953 Truth was acquired by new owners and subjected to an editorial policy in line with the internationalist outlook of the Conservative Party’s post-war leadership. A lesser man than A.K. might well have found a way to adjust to the new realities, but A.K’s response was to stay true to the spirit of what Truth had once been by founding the journal Candour.

It is at this point of the story that we meet the mysterious R.K. Jeffery, a millionaire Englishman based in Chile, who proved to be A.K.’s greatest benefactor, donating the large amount of money that Candour and later the League of Empire Loyalists (LEL) needed to stay in the fight. One of the most interesting parts of the book concerns the later death of Jeffery and the apparent shenanigans carried out by his relatives that prevented the inheritance coming into the hands of the LEL. Who knows how Jeffery’s millions might have impacted on British nationalist politics?

Jeffery’s generous donations during his lifetime, however, were essential to the running of Candour, as it was exactly the kind of publication that, in our pre-internet era, could not but lose money:

As 1954 progressed, Candour’s nature was becoming more and more clear. It was following in the tradition of what Hilaire Belloc meant, just after World War I, when he referred to the ‘free press’ — little papers, unsubsidised by advertisements, consequently running at a loss and necessarily not of mass appeal. (18–19)

But A.K. was not content to sit back and simply run Candour on donations. He soon decided on a more activist approach. He felt that the magazine and its mission would be best served by kicking up some controversy. So, just as the founding of Candour developed directly out of the betrayal of the original purpose of Truth, so the foundation of the LEL addressed a direct need to garner publicity by challenging the acquiescence with which most of Britain was accepting the post-colonial, globalist settlement.

Rather than being a political party, as it is sometimes described, the LEL was designed to be a pressure group “which would force upon existing parties policies favourable to national and imperial survival.” Because of its position on the political spectrum, however, it was always going to exert much more of an influence on the Conservative Party, especially as the UK was in a prolonged period of Conservative rule (1951-1964).

It is sometimes said that the chief British sin is politeness, because it allows a multitude of other vices to flourish unchecked. There was an element of this in 1950s Britain, where important issues like non-White immigration, the future of Britain’s colonial possessions, and the country’s increasing subservience to America were considered “awkward issues,” which tended to be swept under the carpet.

The role that the LEL found for itself was to show up at these exact points and kick up a fuss. The methods employed were a variety of eye-catching stunts that the mainstream media would find hard to ignore.

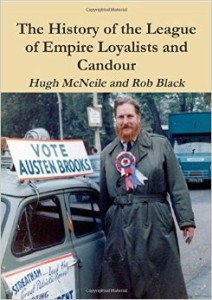

The book contains several examples. While A.K. was the “spiritual leader” of this movement, it was people like John Bean, Austen Brooks, and Leslie Green who carried out the actions necessary to catch the headlines. The best way to describe this to the present generation is to compare it to a pre-internet and very physical form of “trolling.”

Brooks in particular was an ideal example of the LEL activist — a large man with a bushy red beard who was prepared to do anything to challenge the cosy consensus of the post-war world.

When a Soviet delegation, including Prime Minister Nikolai Bulganin and Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party Nikita Khrushchev, visited the UK in 1956, Brooks and other members had a large wooden spoon constructed, which they then delivered to 10 Downing Street, making the point that those who “sup with the devil” need a long spoon.

Brooks was also on duty in 1962 to deliver a bargepole to 10 Downing Street when the Kenyan leader, Jomo Kenyatta, associated with the Mau Mau and other vile atrocities, visited the UK.

Other stunts enacted by the League included heckling meetings of the Conservative Party and Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (often with physical removal from both), defacing posters, disguising as bishops and non-Whites in order to infiltrate meetings, and seizing the UN flag two years in a row on UN Day. There was one issue for which League members were prepared to go a little further, namely insults to the Queen:

The dripping wet Tory peer, Lord Altrincham, had his face publicly slapped by the diminutive 64 year old Phil Burbidge for having written an article attacking the Queen. Pictures of ‘that slap,’ as it became known, filled the front pages of all the dailies and were wired to newspapers in places as far apart as New York, Durban, and Hong Kong. (p.49)

There is a prankish quality to a lot of the activities mentioned in the book that brings to mind student rag days. To many, attempting to give Prime Minister Anthony Eden a coal scuttle because he had “scuttled” the British Empire by backing down over Suez, seems almost buffoonish. But there was a logic to these acts, in that they gained some mainstream media publicity and showed that the post-war consensus was not as cosy as some liked to pretend it was. In short, given the League’s limited resources, it was an efficient way to get their points across while also, no doubt, boosting sales of Candour.

But the LEL was not simply limited to “trolling” government ministers, as they hobnobbed with Soviet politicians and African leaders. The movement also built up an international network of like-minded people. A.K. made several trips abroad, particularly to Rhodesia and South Africa, where he had been born.

As long as the LEL was mainly attacking the incumbent Conservative party, it faced little organized opposition itself and retained the initiative, although Tory stewards resorted to increasingly strong arm tactics, as at this 1958 Blackpool rally, addressed by Prime Minister Harold MacMillan:

The roughest and most brutal handling was reserved for Don Griffin. As MacMillan spoke on unemployment, he shouted out that membership of a free trade scheme with Europe would only worsen it. At this, the temper of the Tory stewards broke in all its fury on him. The News Chronicle’s reporter saw one hold the Loyalist’s arms fast to his side, another gripped his nose, a third covered his mouth, and a fourth lunged at what could be seen of the rest of his face, while an outraged Tory matron assisted by twisting his testicles. (p.68)

It is hard to deny that there was a kind of symbiosis between this incarnation of the League and a Conservative Party that was then moving fast towards the centre and increasingly betraying any sense of British interest.

As Labour started to come to the fore — they were elected into power in 1964 — the LEL lost much of its reason to exist. As a pressure group on the right of the Conservative Party, it was difficult for them to exert a similar kind of pressure on the Labour Party; and with the Conservatives now out of office, they had less ammunition to attack that party. This was reflected in falling membership and funding issues. This strengthened the tendency towards the LEL becoming a political party that would see it merge into the National Front in 1967.

Today there is a tendency to see the LEL as quixotic types, firmly ensconced on the “wrong side of history.” But this perception is questionable. The African leaders, like Kenyatta, whom the LEL ‘trolled’ with a barge pole, really were filthy in every way, from indices of corruption to metrics of murder and massacre.

The same could be said for the Communist leaders whom they also opposed. In 1956, Khrushchev might have been able to point to the scientific pretentions of the Soviet Union and claim that this was “the future.” But, of course, it is old school Communism that now lies rusting on the scrap heap of history.

As for empire, immigration and free trade issues, was the League really far wrong there? On immigration the trends increasingly march in their direction, while on the subject of decolonization, it is obvious that Black Africans were not ready to run their own affairs at that time, while ordinary Blacks in Africa have never been less free and more oppressed than they are now.

A.K. was a firm realist about Africa and knew the continent and its people intimately. Given the inability of African countries to succeed on their own, it is conceivable that sometime in the future, there might well be a need for some kind of formalized mentoring relationship between Europe and much of Africa, not entirely unlike the latter stages of British colonialism or Rhodesia’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence.

While a creature of the past, one suspects that the League and its narratives may yet acquire a new relevance in the future. This is the spirit in which to read this lucid and well-written book, not merely as a remnant of a fading past.

One last thing to mention is that the book is illustrated with dozens of photos, which help the reader to put faces to names. Highly recommended for White Nationalist bookshelves!

Comments are closed.