Review of David Cesarani’s “Final Solution: The Fate of the Jews, 1933–49” — Part Three of Five

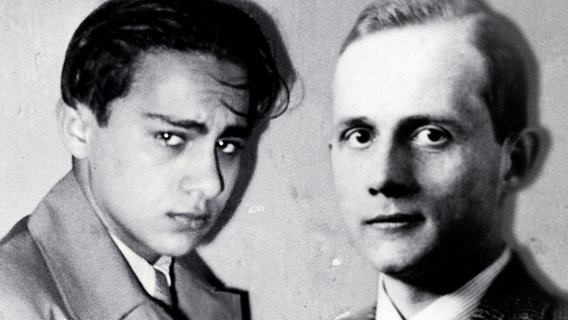

Ernst vom Rath (right) and his Jewish assassin Herschel Grynszpan

“On the explicit order of the very highest authority setting fire to Jewish shops or similar actions may not occur under any circumstances.” Rudolf Hess, November, 1938.

The Complexities of Judenpolitik, 1933–1939, Continued.

Until 1935 the security police (SD) “had only a minor interest in Jewish affairs and had no specific department dealing with the Jews.” Its focus only shifted to this domain in order to monitor public opinion on the Jews with the aim of preventing inter-ethnic violence. One 1935 report noted that because a Jewish “re-conquest of the economy” appeared imminent, further legislation was probably required to check such an eventuality and avoid public anger. After the Gestapo reported on East Prussia where “the number of cases where Jews sexually abused Aryan girls is also on the rise,” it remarked that local and police officials were struggling to keep popular anger and “defensive measures” within the law.

Although Cesarani doesn’t discuss the matter, at the heart of this increasing friction was the age-old tenacity displayed by Jewish populations even when faced with deep unpopularity. Raised— indeed indoctrinated — with the notion that they are resented by the surrounding population, Jews have proven adept at clinging to a host population even in extremely adverse conditions. Jews have also proven extremely capable of forming counter-strategies in which they can maintain or expand influence in such situations. For this reason the forced expulsion features to a significantly greater degree in Jewish history than the exodus.

Cesarani presents some interesting insights into German awareness of this reality, and their theories on how to deal with it. Contemporary Gestapo reports speculated that the Jewish intention was “to steal slowly their way back once again into the Volksgemeinschaft,” and that Jews simply refused “to comprehend that they are only aliens in the Third Reich.” Cesarani neglects to go into detail on this important point, however, and in my opinion radically understates the importance of its most important theorist. Reinhard Heydrich was one of the more intellectual and capable members of the security apparatus, and was particularly concerned with the tenacious aspect of Jewish behavior. In his perfectly readable biography of the SS man, Robert Gerwarth notes that Heydrich’s wife recorded in her diary around this time stating that “in his eyes Jews were … rootless plunderers, determined to gain selfish advantage and to stick like leeches to the body of the host nation.”[1] In one memorandum, Heydrich noted the failure of existing legislation to reduce Jewish influence — something the National Socialists had claimed they would achieve. Instead “the expedient Jewish organizations with all their connections to their international leadership continue to work for the extermination of our people along with all its values.”[2] Since their presence was harmful, directly and indirectly, Jews had to be strongly deterred from pursuing their existence in Germany. Violence and “crude methods” were rejected out of hand, but further legislation would be required.

This tension between an exploited host population and a tenacious middleman minority reached a climax in August 1935 when a government meeting was held in an attempt to remedy the situation. Present were the Minister for Economics, the Interior Minister, the Justice Minister, and the permanent secretary of the Foreign Office. It was quickly agreed that “serious damage to the German economy” was brought about whenever rogue actions took place against Jewish businesses or property, adding fuel for the exaggerations of the Jewish press, and that some legal basis for ending Germany’s ethnic unrest needed to be put in place. Hitler was only moved to finally take action on these recommendations when Jewish demonstrators in New York boarded the liner Bremen, seizing the vessel’s swastika flag and tossed it in the Hudson. Sensing a breaking point at home, he consented to the development of racial laws aimed at segregating the two races and restoring order. He announced these laws on the last day of the Nuremberg Rally, explaining that they were a response to “international unrest.” Reflecting back on their key purpose, he added that “the government was meeting this challenge head-on by legal means and warned that random acts of revenge by party zealots were no longer acceptable.” On the contrary, he anticipated that with the new legislation in force “the German people may find a tolerable relation towards the Jewish people.”

As in the case of earlier legislation, the Nuremberg Laws were greeted with an outcry from International Jewry, and they continue to be subjected to condemnation in most histories of the Third Reich. However, Cesarani admits that many German Jews saw the benefits of such laws and that their general response was “one of relief.” Jews had their political influence further reduced, but “the economic rights of those still in trade and business were not affected.” Cesarani gets side-tracked into anecdotes intended to provoke sympathy for some of those affected, but they strike a bum note. For example, he discusses a very wealthy Jewish family that “had to dismiss their maid, which meant more housework for Luise” — a small price to pay for the promise of stability, might one argue, and the removal of potential points of inter-ethnic friction.

The security police noted that the legislation was starting to achieve the desired effect in terms of securing a peaceful nation that nonetheless encouraged more Jews to consider leaving. Pro-assimilation organizations began to decline, and there was an increased interest in Zionism. Despite the ongoing propaganda campaign in the Jewish press, the international Jewish community was mostly muted and seemed to accept the rights and wishes of Germans to stop sharing their soil, political institutions and economy with a different ethnic group. Although the Centralverein noted that Jewish trade was actually improving, and many Germans still had Jewish bosses, popular unrest also slowly dissipated. The legislation had once again struck a masterful balance, easing some of the inter-ethnic pressure. Police reports from Berlin indicated that for the German population, the laws had “cleared the air and brought clarity.” As a sign of their effectiveness, the new peace even survived extreme provocation when a Jew, David Frankfurter, shot dead the leader of the Swiss Nazi Party on February 4, 1936.

Some causes of ethnic friction persisted, and these festered over time. By 1937, four years after the advent of the National Socialist government, Jewish cattle traders remained in a strong position in the countryside, and letters were still arriving from county commissioners complaining that, to use Cesarani’s phrase, “Jews continued to have too much influence.” Jewish lawyers were still in German courts, and “thousands of Jewish children were still at state schools.” Emigration had stagnated once again, and in the foreign sphere France was now under the socialist rule of the Jew Léon Blum. Foreign provocation also accelerated when in March 1937 the part-Jewish Mayor of New York, Fiorello LaGuardia delivered an anti-German speech at the American Jewish Congress replete with atrocity propaganda.

In response, the Germans imposed a two-month ban on the AJC’s German equivalent, the CV. The ban was the subject of yet another international press outcry. Challenges also accompanied the Anschluss with Austria in 1938. As decades of built-up “high pressure” struggled for release in the newly annexed territory, the German security forces were forced to come down hard on Austrian members of the NSDAP. Heydrich threatened arrest for anyone who deviated from the legislative processes of the Reich government, and stressed that “foreign domination of the economy would be tackled through the law.”

Cesarani points out that the German legislation was seen as very effective by neighboring countries with similar ethnic problems. In Romania “around half of the Jews were engaged in commerce … . They dominated the bourgeoisie of Bucharest … . Romanians noted their preponderance in the professions, in commerce, and the existence of a few fabulously wealthy families who controlled financial or industrial enterprises.” Following the German approach, by the mid-1930s the Romanian government had introduced a policy of “proportionality,” limiting the involvement of Jews in national life to their proportion of the population via a system of quotas.

In Hungary too, government officials took note of German successes. In Hungary, Jews had “dominated segments of economic and cultural life, constituting 55% of Hungary’s lawyers, 40% of its doctors, and 36% of its journalists. Around 40% of the country’s commerce was in the hands of Jewish merchants, retailers and traders. Jews owned 70% of the largest industrial concerns.” Hungary began seeking a legislative response to this reality, settling on a quota system similar to those employed in Germany and Romania. Spoiling this array of staggering statistics is Cesarani’s pointless commentary, utterly senseless and frankly pathetic in light of the material he has just presented: “Anti-Semitic agitators [in Hungary] cultivated a myth of Jewish wealth.”

In October 1938 the National Socialists undertook what many felt would be the last major legislative action against Jewish influence in Germany before the matter was left for emigration and demographics to conclude — the expulsion of the Ostjuden, many of whom were actually in the country illegally. Again, rather than being initiated on ideological grounds, the move was a response to external developments. The Polish government in Warsaw, seeking to take advantage of the movement of its Ostjuden to neighboring nations, decided to strip all Polish emigres of their citizenship. The move would render stateless 70,000 Ostjuden residing in Germany, making it even more difficult to deport them than was already the case. In an attempt to beat the clock before the Polish law fell into place, the Gestapo began a hurried operation to arrest and deport 17,000 of these Polish Jews, beginning on October 27, 1938. Although only a fraction of the vast Polish Jewish population was targeted, and “some ended up back in Germany,” the international press bewailed the latest unprovoked “assault on the Jews.”

The media exaggeration would prove fateful. Already seething at the deportation of his parents from Germany, Herschel Grynszpan, a Polish Jew living illegally in France, was further incited by sensationalized accounts that heaped blame exclusively on the German government. Furious, the Jew walked into the German Embassy in Paris and shot dead a young official named Ernst vom Rath. The murder was not the first diplomatic or political casualty of Jewish violence and came just two years after the high-profile murder of Wilhelm Gustloff by David Frankfurter.

Historians have since argued that the German government, and Goebbels in particular, over-reacted to the murder and inaccurately portrayed it as an assault by Jewry against Germany. Cesarani continues in this vein, contending that Goebbels “blew it out of proportion.” However, it is an inarguable fact that both Frankfurter and Grynszpan were acting as Jews, incited by Jewish propaganda, and possessed specifically Jewish grievances. Coupled with physical agitation in the United States, including the boarding of the Bremen mentioned above, the picture that inevitably emerged was one of unified, consistent and violent activity by Jews against the German government. Berlin’s chief of police was therefore not acting unreasonably when he issued an order for all Jews in the city to hand over their firearms, nor was the Gestapo when it reacted to the news by shutting down Jewish newspapers in the German capital. What the government couldn’t do was manage to keep the “high pressure” of the population from briefly boiling over.

The “night of Broken Glass” which is endlessly regurgitated to school children the world over has been wildly exaggerated. On November 9, 1938 damage to Jewish property certainly took place, as did a number of isolated assaults and even deaths. However, as Cesarani concedes, the security police were mobilized almost immediately “to prevent looting,” and the event was remarkably mild when considered among the annals of inter-ethnic violence. The government also severely punished the violence and disorder. As Cesarani notes, “historians know so much about the November pogrom because it was subject to disciplinary hearings by the Nazi Party.” It has long been known that “there were no orders to kill anyone. Nor were there any instructions to wreck Jewish commercial premises.” The events of the night actually “provoked the wrath Göring and Himmler … and resulted in a backlash at home and abroad.” Focussed on encouraging emigration, Heydrich and the SD[i] “despised” the chaos, and Adolf Eichmann was “apoplectic” when he discovered that the Jewish office for emigration had been ransacked. On the afternoon of November 10, the Party broadcast a message issuing “a strict order … to the entire population to desist from all further demonstrations and actions against Jewry, regardless of what type. The definitive response to the Jewish assassination in Paris will be delivered to Jewry via the route of legislation and edicts.”

During the panic and chaos following the murder of vom Rath, thousands of Jews had been arrested and taken to concentration camps, some with the aim of protecting Germans and some with the aim of protecting Jews. Although the arrests were once again the subject of hysterical reporting in the international press, within a few days the vast majority had been released on the personal orders of Heydrich. Around the same time Göring met with business leaders and insurance companies to assess the damage and arrive at a means of moving forward. The Jewish Question was, Göring argued, “essentially an economic question though it would need legal measures to achieve a solution. … The public needed to understand that rioting was no panacea.” At one point Göring cried out with exasperation, “I have had enough of demonstrations!”

The cost of November 9th was exorbitant. Some Jewish businesses may have been damaged, but it was the pay-outs of German insurance companies that hit the German economy hard. When discussion moved to preventing future instances of disorder, it was conceded that foreign Jewish assaults on German diplomats couldn’t be predicted or prevented, leaving the spotlight on the management of relations within Germany. The only viable solution was to continue using legislation to reduce the Jewish presence in Germany, thus reducing inter-ethnic friction.

As a result of a chain reaction of events commencing with Jewish aggression and assassination, the German government introduced a Decree on the Exclusion of the Jews from German Economic Life. In addition to the social clauses of the Decree, the legislation was aimed at decisively encouraging the peaceful, non-violent departure of Jews from Germany. It was the continuation of a policy favoring exodus over expulsion. However, even for legislation aimed at pushing a problematic group to peacefully depart, it was far from all-encompassing.

For a start, over 700,000 mixed-race individuals were exempted from the legislation even if they identified as Jews. Foreign governments protested loudly, mainly at the instigation of their Jewish populations. But there was sufficient awareness of ethnic realities even among these foreign saints, that none were willing to take in the growing number of German Jews now willing to emigrate. The United States, Britain and France feared that any willingness to take Germany’s Jews would be seen as an invitation to other countries like Romania and Hungary to divest themselves of their “Jewish Problem” also, leading to mass Jewish immigration into their countries. Rather than take in these “innocent victims” it was vastly preferable to let mass inter-ethnic tension bubble elsewhere and criticize a host of native populations for not liking it.

At the outset of 1939 Hitler gave a speech to the Reichstag on the state of international politics. He ridiculed the hypocrisy of the democracies for believing sensationalized accounts and for “condemning Germany’s treatment of the Jews while refusing to accept Jewish immigrants.” Jews, he argued, could contribute to a peaceful Europe, but the only way they could do that would be by adapting “to constructive labor elsewhere in the world.” Although much in the speech has been presented in a threatening, negative light, modern scholarship has come to the conclusion that it was actually a “rhetorical gesture designed to put pressure on the international community to expedite the mass emigration of the remaining German and Austrian Jews.” After six years of atrocity propaganda, provocation, and assassination, it was a call on Jews to finally accept the wishes of the German people that they no longer desired co-existence, and a call on the Western democracies to “put up or shut up.”

By this time (early 1939), it does appear that Jewry had given up on maintaining a presence in German territories. Jewish agitation for increased immigration quotas was relentless, particularly in the United States. State Department official J.P. Moffat remarking that “the pressure from Jewish groups all over the country is growing to a point where before long it will begin to react very seriously against their own best interests. … No-one likes to be subjected to pressure of the sort they are exerting.” The French foreign minister, Georges Bonnet even “accused French Jews of sabotaging good relations with Germany by harping on about the suffering of their co-religionists.”

However, Jewish leaders were reluctant to cover the cost of the withdrawal themselves, and resorted to applying pressure to politicians and haggling with governments. Cesarani writes that “Jewish leaders in London and New York looked askance at a scheme that enjoined them to finance the orderly emigration of German Jewry.” They preferred to transfer the cost to non-Jewish taxpayers. In Britain, after the creation of the Reich Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, influential Jews managed to persuade the government to provide £4 million for the re-settlement of Czech Jews in England. U.S. State Department official Robert Pell is reported by Cesarani as writing on May 15, 1939 that: “My candid impression is that our business is becoming a tug of war between the Government and our Jewish financial friends. The Governments are striving hard to shift the major part of the responsibility to Jewish finance and Jewish finance is working equally hard to leave it with the Governments.”

The tug of war took place against a backdrop of tensions in which Germany pressed its rightful claim against the Polish government to the port city of Danzig. Media treatments of the German prerogative were dismissive and hateful, hyping the tension beyond reason. Jewish outlets worked overtime to link Germany’s legitimate territorial demands with its mythologized version of National Socialist Judenpolitik. On September 1, 1939 German troops crossed the border into Poland. Britain and France declared war on Germany.

The efforts of six years of pursuing peaceful Judenpolitik lay in ruins. Taking to the podium of the Reichstag, a shocked but defiant Hitler told Party members: “Our Jewish democratic global enemy has succeeded in placing the English people in a state of war with Germany. … The year 1918 will not be repeated.”

Thus closes the last of Cesarani’s chapters dealing with Judenpolitik. The historians among our readership will of course note there is little factually novel or different about the fare presented here. For example, it’s long been known that the “night of Broken Glass” was preceded by the assassination of Ernst vom Rath. However, what is novel is the subtle yet palpable change occurring in mainstream scholarship in terms of the emphasis it lays on different aspects of what occurred between 1933 and 1939.

To elaborate, there is a significant difference between accounts which state that the assassination offered the National Socialists an opportunity they were practically begging for, and accounts which argue that the assassination actually confirmed the worst fears of the German leadership in terms of Jewish violence, while also providing them with a serious challenge to law and order, economic stability, and international reputation. What Cesarani’s tactical concessions illustrate more than anything is that National Socialist Judenpolitik will increasingly be understood less as the vulgar ideological crusade so many Jewish propagandists have portrayed it as, and more as an ethnically-motivated, complex, even occasionally successful performance of politics.

[1] R. Gerwarth, Hitler’s Hangman: The Life of Heydrich (Yale University Press, 2012), 93.

[2] Ibid, 94.

Comments are closed.