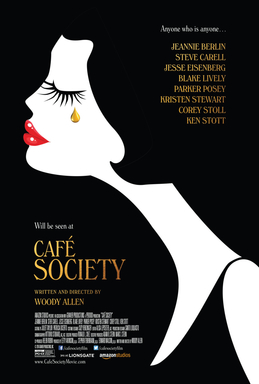

Woody Allen’s Café Society

“I have never been so upset by a poll in my life. Only 22% of Americans now believe “the movie and television industries are pretty much run by Jews,” down from nearly 50% in 1964. The Anti-Defamation League, which released the poll results last month, sees in these numbers a victory against stereotyping. Actually, it just shows how dumb America has gotten. Jews totally run Hollywood.” [i] — Joel Stein

Woody Allen’s crepuscular film Café Society (2016) is as boring as it is instrumentally instructive as a testament to Jewish cosmopolitanism, domination and reshaping of American values and culture. Set in the 1930s the film centers on Bobby Dorfman (Jesse Eisenberg), the youngest son of a New York Jewish family, who leaves his father’s jewelry business for Hollywood. If Fellini used Mastroianni, as an idealized surrogate-self, Eisenberg is used rather as Allen’s mirror image, neurotic, shlumpy, physically weak, lascivious, overtly sentimental but quick-witted, clever with high verbal acuity – a certain Jewish je ne sais quoi.

Jesse Eisenberg, Kristen Stewart, and Woody Allen, on the set of Café Society

The conflation of Dorfman and Allen is made even more obvious with Allen’s voiceover narration throughout. The Dorfman family trio functions as a trio of Jewish stereotypes, his elder brother a gangster, his sister married to a Marxist intellectual, and both he and his uncle settled in the entertainment industry. Radical intellectualism and entertainment are a microcosm of the Jewish cultural enterprise, and the explicitly crude expression of usurious tendencies in the gangster are a stand-in for a still-common Jewish phenomenon of exploitative business practices (see Andrew Joyce’s “Jews and Money Lending: A Contemporary Case File”). Each of these enterprises supports and affirms the other.

Continuing with the Jewish stereotypes, Allen intersperses scenes with Jews who fleetingly pass off stock tips, whispering in an ear at a party – implicitly showcasing ethnic networking.

The film is illustrative of the immense and impressive penetration of Jews into American elites, but with most of the focus on the cultural elements rather than the purely economic or criminal. Jews have dominated the cultural scene in American life at least since World War II, much as they had in the cosmopolitan centers of Europe. In fact, knowing nothing of the movie, I had assumed that its title referred to Vienna, the central hub of Jewish Mittel-Europa known for its famous “café society.” Indeed, the parallels between Jewish control and domination of fin-de-siècle Vienna and modern America are too numerous to be merely coincidental, and it’s worth mentioning that Jewish domination of cultural life in Vienna was a potent source of anti-Semitism. As one pan-German paper of the period put it, “the products of a ‘degenerate afterculture’ of the ‘modernists’ should well be banned. … Everything that is sacrosanct to us, our people’s customs, our ancestor’s way,’ was in danger of becoming ‘Jewish-contaminated.’”[ii]

Unlike the rich cultural traditions of the Old World, America, with its explicit liberalism, heterogeneous demographics, utilitarian and egalitarian philosophies, hyper-capitalism, and anti-traditionalism, was already, whether it knew it or not, open to Jewish influence. Jews had far fewer obstacles in their rise to elite status, and used culture as a springboard to alter American perceptions and values to their advantage. As Harold Cruise puts it in Crisis of the Negro Intellectual:

But the Anglo-Saxons and their Protestant ethic have failed in their creative and intellectual responsibilities to the internal American commonweal. Interested purely in materialistic pursuits—exploiting resources, the politics of profit and loss, ruling the world, waging war, and protecting a rather threadbare cultural heritage—the Anglo-Saxons have retrogressed in the cultural fields and the humanities. Into this intellectual vacuum have stepped the Jews, to dominate scholarship, history, social research, etc.”[iii]

In this passage Cruise accounts for two aspects of Jewish cultural control, as represented by the film’s characters —the media and intellectual high ground. The third component, gangsterism, and general lawlessness (Meyer Lansky, Bugsy Siegel, Dutch Schultz) are related metaphysically to the other two elements. They are a direct expression of a central feature of Jewish consciousness, as each is propelled by a disregard for social limits. For Jews, the rules do not apply, since after all the rules are established by a society that is not their own.

The film is set half in California and half in New York, the two central hubs of Jewish domination of American culture and society and reflecting Michael Novak’s comment: “A relatively small number of Jews in New York and Los Angeles set a style for Jewishness that may be foreign to Jews in Cleveland or Utica.”[iv] It’s a style that is foreign to the traditional people and culture of America.

The central focus of the film is the story of how Jews came to dominate American culture and secondarily (and not coincidentally) how they came to dominate non-Jewish women. Indeed the central narrative element moving the story along are romantic relationships of Jewish men with WASP women. Dorfman travels to Hollywood to work for his Uncle Phil (Steve Carell), an industry power broker. Dorfman is stunned by his uncle’s young assistant, Veronica (Kristen Stewart), who is tasked with showing Dorfman around Hollywood. During these pseudo-dates the two grow fond of one another and begin an intimate relationship—at the same time as powerful Uncle Phil is having an affair with her. The obvious message is that power in Hollywood translates into sexual access to beautiful, young White women.

While, the film is set in the 1930’s, I was also reminded of the treatment and condition of scores of non-Jewish women in “Hollywood’s seedier cousin,” another Jewish-dominated enterprise, the adult film industry, wherein White women are passed around like ‘liberated’ Valley of the Dolls extras to reenact the tragedy of Norma Jean on film:

“It is clear,” says Anthony Summers in his biography, “that Marilyn made judicious use of her favors. A key beneficiary was the [Jewish] man who got Marilyn that vital first contract at Fox — Ben Lyon. According to writer Sheila Graham, Lyon had been sleeping with Marilyn and promising to further her career . . . Lyon called the casting director for Sol Wurtzel, a [Jewish] B-movie producer of the time [and Monroe was awarded a small part in the 1947 film Dangerous Years]” (Summers, 35).

In olden times,” Upton Sinclair once remarked, “Jewish traders sold Christian girls into concubinage and into prostitution, and even today they display the same activity in the same field in southern California where I live.” Or as F. Scott Fitzgerald summed up the Hollywood scene of his era — “a Jewish holiday, a Gentile tragedy” (Gabler, 2).[v]

When the revelation of the love triangle is discovered, Veronica makes the decision to marry the established and wealthy Phil, explicitly because of his wealth and power. Phil then divorces his wife, and Dorfman goes back to New York with memories of his idle time spent with Veronica, a woman vastly out of his league.

Back in New York Dorfman runs a high-end nightclub that his gangster brother Ben (Corey Stoll) started. There Dorfman meets an even more out-of-his-league gentile woman, the statuesque Veronica Hayes (Blake Lively), and the two begin to date, marry and begin a family. Hayes is used as a kind of prized Rainbow Lorikeet in a gilded birdcage, the shiksa in the designer dress and lush apartment. The fact that both are named Veronica may point towards the effective consumable quality of each.

Blake Lively (left) and Kristen Stewart, in Café Society

The Sunday evening audience, comprised mostly of geriatric Jews, gasped when Southern belle Hayes made some classic anti-Semitic remarks as Dorfman was aggressively coming on to her: “god you people are pushy” (gasp), and ‘where I’m from, you’re not supposed to mix with Jews.’

Of course, Hayes has left her Southern heritage behind, and has become a rather one-dimensional prop illustrating the prototypical liberated woman who can choose her associations with no concern for group-loyalty. Her loyalty is the Carrie Bradshaw variety — loyalty to high-end brands, cosmopolitanism, and sexual liberation.

If the audience was a bit upset by Hayes’ slightly offensive, antiquated, and toothless anti-Semitism, it relished a bit of Jewish inside humor. When the gangster brother who had converted to Christianity was electrocuted for his crimes, his mother laments, “my son first a murderer, now a Christian,” implying the latter is worse (laughter).

Overall, the film was overly sentimental (the ending is truly bathetic), with one-dimensional, allegorical characters meant to represent interesting and historically important Jewish stereotypes — albeit stereotypes with a substantial degree of truth. In content and execution it reminded me of Steve Martin’s Shopgirl (2005) with the same monotonous sweeping aimlessness, aridness, and near pointlessness. Except for the little signposts that said that, at the end of the day, this was a deeply Jewish allegory.

[i] http://articles.latimes.com/2008/dec/19/opinion/oe-stein19

[ii] Hamann, Brigitte. Hitler’s Vienna : a portrait of the tyrant as a young man. London: Tauris Parke Paperbacks, 2010. Print. 84.

[iii] Cruse, Harold. Crisis of the Negro intellectual. London: W.H. Allen, 1969. Print.

[iv] Novak, Michael. Unmeltable ethnics : politics & culture in American life. New Brunswick, U.S.A: Transaction, 1996. Print.

[v] http://www.counter-currents.com/2011/08/who-killed-marilyn-monroe/

Comments are closed.