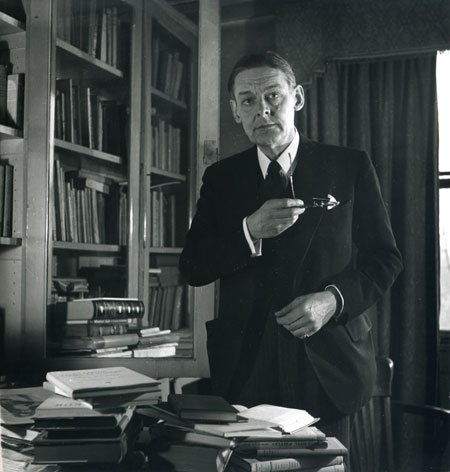

T.S. Eliot and the Culture of Critique, Part Two

‘We must discover what conditions, within our power to bring about, would foster the society that we desire. … Reasons of race and religion combine to make any large number of free-thinking Jews undesirable.’

T.S. Eliot, After Strange Gods, 1934.

One of the most striking features of Julius’s T.S. Eliot, Anti-Semitism, and Literary Form is that it is no mere literary critique. This basic and relatively short work is a multi-pronged and vicious ad hominem masquerading, with odious pretentiousness, as criticism. Eliot, the man, is attacked in multiple, often scurrilous, forms throughout.

These are subtle attacks, perpetrated under the cover of a flimsy, indeed petulant, thesis. This thesis, such as it exists, is two-dimensional. Summed up, it consists of two basic arguments. The first is that Eliot drew on “anti-Semitic” themes for some of his poetry, themes that were characterized by their disdainful attitude towards Jews. The second is that “anti-Semitism” was an intrinsic part of Eliot’s art, and therefore Eliot himself was ‘anti-Semitic.’ Of course, in and of itself, the accusation that Eliot wasn’t fond of Jews is hardly damning. However, in the hands of Jewish ethno-activists the accusation of “anti-Semitism” is often loaded with deeper and more insidious aspersions. As such, the thesis and the ad hominem nature of its arguments and content are bound up intricately via a single common thread: Julius’s own corrupt understanding of what “anti-Semitism” is.

Julius’s professed understanding of anti-Semitism is identical to that of other Jewish ethno-activists. In this perception, “anti-Semitism” is a mixture of “incoherent” discourses riddled with “internal contradictions.”[1] It arises, at worst, in the sick, irrational mind. At best, it develops ex nihilo, since, as Julius puts it, “no external factor can induce it.”[2] In this remarkable psychological bubble, Jews are entirely blameless. Ever passive, they lack all agency. They exist merely to register the irrational mental undulations of “the nations,” that confused, miasmic mass of humanity they have been tasked by Jehovah to act as a “light unto.” The problem with such a perception, of course, is the existence of an overwhelming amount of contradictory evidence.

Even in the specific case of T.S. Eliot there is no shortage of evidence as to why the great poet may have developed a dislike or distrust of Jews. In the first instance, and like Julius, he may have been influenced by family history; except that in Eliot’s case the family history was more immediate and genuine. To be more specific, Eliot’s mother Charlotte informed him in the early 1920s that her own father, the merchant Thomas Stearns, had a number of bad experiences with Jews in Boston and thus “Father never liked to have business dealings with them.” Charlotte also informed T.S. in the same letter that Jews “took advantage of Henry [Eliot, father of T.S.] in the Publisher’s Press.”

Eliot himself also had a number of bad business transactions with Jews, in particular with Horace Liveright, his Jewish publisher in New York. Liveright was apparently reluctant to pay Eliot monies owed, prompting Eliot to write to his agent in 1923: “I am very annoyed about this, although it is the sort of behavior I have been led to expect from Liveright. I am sick of doing business with Jew publishers who will not carry out their part of the contract unless they are forced to.”[3] Liveright, founder of Modern Library, was a particularly notorious crook who exploited the talent of others. As well as publishing Eliot’s The Waste Land, Liveright also published the first books of Ernest Hemingway and William Faulkner. In the late 1920s he would turn to theatre, taking in $2 million for a production of Dracula — and failing to pay the meagre $678.01 in royalties he owed to Florence Balcombe, the widow of Bram Stoker.

We can see these real-life interactions translated in the poetry of T.S. Eliot. Eliot’s Jews are petty capitalists, grubby, greedy, untrustworthy, and only tangential to the heart of the action. In Gerontion (1920) Eliot’s Jew is landlord to the protagonist. He “squats on the window-sill, the owner” peripheral to the center yet leeching from it. He is also international, being “Spawned in some estaminet of Antwerp, Blistered in Brussels, patched and peeled in London.” Similarly, in Burbank with a Baedeker: Bleistein with a Cigar (1920) the Jewish Bleistein is characterized by internationality and a lack of social or aesthetic grace:

But this or such was Bleistein’s way:

A saggy bending of the knees

And elbows, with the palms turned out

Chicago Semite Viennese.

The last line of the stanza emphasizes again the international or indeterminate origin of Eliot’s Jews — a reflection of the poet’s own difficulties in “pinning down” the often slippery characters he dealt with. Even when physically pinned down, their responsibility for wrongs could be just as elusive, with Bleistein notably turning out his palms in the familiar, muted, gesture of pleading innocence. Later in the poem are the notorious lines:

The rats are underneath the piles.

The jew is underneath the lot.

Money in furs.

This passage is quite probably drawn from Eliot’s growing perception that Jews were almost omnipresent in publishing, advertising, and other important aspects of business and culture that he was forced to deal with. In the same 1923 letter to his agent in which he decried the “Jew publishers,” Eliot had added: “I wish I could find a decent Christian publisher in New York.” [4] Although this rising class of Jews was influential, ultimately Eliot perceived such figures as lacking social grace or genuine class. To Eliot they were full of social pretension, mere “money in furs.”

If there is any substance to the idea that Eliot may have been referring to a deeper form of Jewish subversion in this part of the poem, some insight may be gained from his 1925 correspondence with the poet and critic Herbert Read in which he discussed his attitudes to Jews and their involvement in Bolshevism: “I am always inclined to suspect the racial envy and jealousy which makes that people [the Jews] inclined to Bolshevism in some form (not always political).” Eliot’s ominous addition of the phrase “not always political,” may now be regarded as a remarkably prescient understanding of cultural Marxism some four decades before it made its first real impact.

In yet another poem, Sweeney Among the Nightingales (1920), the protagonist lies slumped in a dive, probably drunk. Around him are a number of suspect individuals and the atmosphere is tense and hostile. A man, possibly a pimp, gapes through the window at the scene with a grinning mouth full of gold teeth. One of the women present is “Rachel née Rabinovitch,” and she “Tears at the grapes” in front of her “with murderous paws.” Here Eliot hints at the well-known dominance of Jews in the international traffic in prostitution in the early decades of the twentieth century,[5] and again references the indeterminate origins of many Jews, in particular the habit of “passing” as non-Jews via a name change. Eliot “exposes” Rachel by referencing her last name at birth, but ultimately she exposes herself via the same social gracelessness that Eliot perceived in those Jews he interacted with, and that he ascribed to Jews in other of his poems.

In the entire body of Eliot’s poetic output these brief, and entirely explicable, instances comprise the only direct references to Jews. And yet they have consumed Jewish critics, and Anthony Julius in particular. The reason is that they provide meagre, though much-needed, fuel for what Frank Underhill described as the “persecution complex.” Julius writes that Gerontion “stings like an insult,” its lines implicating “all Jews in their scorn” and making “a Jewish reader’s face flush.”[6] Eliot, argues Julius, “placed his anti-Semitism at the service of his art.”[7]

Because this art was successful and attracted praise it also attracted Jewish hostility. The culture of critique, as it applies to our celebrated and traditional cultural figures, involves scorn of both the artist and those who celebrate them. Julius writes that non-Jews can’t even understand these poems unless they accept that they cause Jewish “pain” since, “to ignore these insults is to misread the poems.”[8] He subsequently seethes that “early hostilities made [Eliot’s] reputation; subsequent attacks failed to diminish it,”[9] and he sets himself the task of achieving just that.

Julius sets out to achieve his goal by going beyond any previous critique of Eliot, by which I mean that he doesn’t stop at the mere suggestion that Eliot possessed an irrational dislike of Jews. Central to his technique is Freudianism, that infinitely plastic theory which can and has been used to “scientifically prove” all sorts of things, including the psychopathology of White ethnocentrism and the unresolved transferences of people who don’t accept psychoanalysis. Thus Eliot is “anti-Semitic” because he loathes himself and therefore “his hostility to Jews may thus contain an element of self-disgust.”[10] Julius resorts to endless and tortured Freudian contortions to ascribe to Eliot a “sordid fascination”[11] with women, a “contempt for women,” and a body of poetry “dramatizing male panic about women.” And, using the most specious Freudian rhetoric, Julius claims that Eliot “broods on the killing of women.”[12] Eliot’s “imaginative projects” are said to include “the dismemberment of a woman.”[13] His work, says Julius, “betrays a sadomasochistic fascination with the erotics of murder and rape.”[14] Eliot’s Christian piety is further evidence of his deep-seated and irrational hatred of Jews since he then becomes a pawn in an “ideological warfare waged by the Church against the Synagogue.”[15]

The only ‘evidence’ upon which Julius bases such lurid aspersions are a handful of lines from four of five of Eliot’s poems which feature, to a minimal degree, references to violence against females. All of Julius’s references in this regard detach themselves from wider context, and represent a rather shameless manipulation of sources (and the reader) that will be unsurprising to those familiar with similar tactics in his Trials of the Diaspora. For example, to support his assertion of Eliot’s preoccupation with rape, Julius refers to the line from the The Waste Land: “Philomel, by the barbarous king, so rudely forced.” (Julius, T.S. Eliot, Anti-Semitism, and Literary Form, 24) What Julius fails to state is that Eliot didn’t just invent this line. The line is actually drawn from the poem’s meticulous interweaving of Greek mythology. According to these myths, the Philomel in question is raped by her sister’s husband, Tereus, but ultimately emerges as a powerful (and vengeful) figure. Were the ancient Greeks also perverts with fantasies of rape and sadomasochistic murder? Does any story or piece of art involving reference to violence against women implicate the author in a hatred of women? Julius doesn’t say, but he does ‘seek out’ misogyny in the same neurotic fashion that he seeks out ‘anti-Semitism.’ He does this because, he asserts with poor articulation, there is a “relation between misogyny and anti-Semitism.” (Ibid., 19) In Julius’s mind, if Eliot was an anti-Semite, then he must have been a woman-hater too. It must have pained the critic when a slew of letters, discovered and published earlier this year, revealed Eliot to have been a caring husband who had normal relationships with women and had “repeatedly shown compassion” to his mentally-ill first wife.

As well as smearing T.S. Eliot as a pervert preoccupied with fantasies of rape and murder, Julius also deploys the more familiar and conventional charge of “racism.” This charge is underpinned flimsily with the sole argument that in one passage referencing the demographics of Virginia, lifted from After Strange Gods, Eliot “overlooks the entire Black population of the South.”[16]

In Julius’s rendition, T.S. Eliot was thus the quintessential White male as imagined by our counter-cultural elites who dominate the academic scene today: hostile to Jews, Blacks, and women. His is arrayed against all of the victim classes as imagined by modern social justice warriors.

And yet Julius persists throughout this work with an almost schizophrenic conviction that he has maintained a sense of fairness and impartiality. After describing Eliot as an irrational zealot and a self-loathing pervert with rape and murder fantasies, Julius writes that it is “difficult to write about Eliot’s anti-Semitic poetry. One risks distorting the work, even defaming the man.”

Is this remarkable dissonance the result of self-deception on the part of Julius? Or a gross disingenuousness? I lean on the side of the latter. No sooner does Julius claim impartiality than he employs a greasy appeal to innocence; the critic as Bleistein. Julius bends his knees and turns out his palms by stating that “When Jewish, one risks even more. One puts in jeopardy one’s credentials as a critic. One can seem a philistine.” He coaxes his readers, with admirable guile, into a reassurance that he is not a philistine; that he should not refrain from critiquing Eliot; that his Jewishness has nothing to do with it.

And yet I believe that Julius knows that his Jewishness has everything to do with it. Because Jewishness is an obsession, above all, to Jews. Julius makes a pertinent point in this regard himself when he recalls a joke common in the Jewish community: “Write an essay on the giraffe, a class is instructed; Cohen submits ‘The giraffe and the Jewish question.’ Everything refers back to Jews.”[17]

Evidence suggests that this joke is grounded firmly in reality. For example, ask a class to write about English literature and ‘Cohen’ will submit:

- Derek Cohen and Deborah Heller’s Jewish Presences in English Literature

- Bryan Cheyette’s Constructions of ‘the Jew in English Literature and Society and his Between Race and Culture: Representations of ‘the Jew’ in English and American Literature

- Harry Levi’s Jewish Characters in Fiction: English Literature

- James Shapiro’s Shakespeare and the Jews

- Edgar Rosenberg’s From Shylock to Svengali: Jewish Stereotypes in English Fiction

- Gary Levine’s The Merchant of Modernism: The Economic Jew in Anglo-American Literature

- Heidi Kaufman’s English Origins, Jewish Discourse, and the Nineteenth-Century British Novel

- Esther Panitz’s The Alien in the Midst: images of Jews in English Literature

- Edward Calisch’s The Jew in English Literature: As Author and as Subject

- Matthew Biberman’s Masculinity, Anti-Semitism, and Early Modern English Literature

- Eva Holmberg’s Jews in the Early Modern English Imagination

- Phillip Aronstein’s The Jews in English Poetry and Fiction

- Nadia Valman’s The Jewess in Nineteenth-Century British Literary Culture

- Frank Felsenstein’s Anti-Semitic Stereotypes: A Paradigm of Otherness in English Popular Culture

- Jonathan Freedman’s The Temple of Culture: Assimilation and Anti-Semitism in Literary Anglo-America

- Sheila Spector’s British Romanticism and the Jews: History Culture and Literature

- Anna Rubin’s Images in Transition: the English Jew in English Literature, 1660-1830

The point worth stressing here is that the neuroticism evident in Julius’s work is much more widespread. The culture of critique is driven by mania and preoccupation, even on such a relatively small level as the life and work of a single writer like Eliot. The Brooklyn-born Jewish writer Delmore Schwartz (1913–1966) (who is commonly grouped among the New York Intellectuals—a Jewish intellectual movement that rose to prominence after World War II; here, p. 217ff) is reported to have been “obsessed” with Eliot’s “anti-Semitism.”[18] Harold Bloom (a second-generation New York Intellectual) has declared his own private “war” against the man he describes as “the abominable Eliot.” Bloom’s campaign has been so obtuse that even the Guardian has described Bloom’s position as “petulant,” particularly his smearing of Eliot in his book Genius (2002), in which he “drags [Eliot] into contemptuous question on the slightest opportunity.”

The aftermath of the publication of Julius’s assault on the personality and work of Eliot has had a marked and lasting impact on the status of the poet, both in terms of encouraging other Jews to engage in similar assaults, and brow-beating non-Jews into acceptance of the smearing. After the publication of Julius’s work, the barely-known Jewish poet Dannie Abse felt emboldened enough to demean the work of Eliot by remarking that “The vicious obscenities of these poems don’t make literature any more than pornography makes literature.” When the non-Jewish Craig Raine attempted to make a spirited public defense of Eliot and his legacy, Julius mocked him with the retort: “It’s like Biggles Raine to the rescue. Hero-worshipping is dangerous and immature.” Raine in turn retaliated with the assertion that Julius had created a “mistrustful critical climate” where students and scholars had been encouraged to search for evidence of “careerism and anti-Semitism” in Eliot’s life and “were almost disappointed at the lack of such evidence.”

Julius on that occasion found himself supported by another Jewish literary figure, this time the author Will Self. Self, in a pattern that should by now be familiar, employed Freudian soundbites to argue that hostility to Julius was due less to his critique of Eliot than to the fact he has since become the divorce lawyer to Princess Diana. According to Self, pro-Eliot figures like Raine were in fact troubled by “the idea that a Jew should be in close contact with our Aryan princess; the woman who is held to be the most inaccessible and therefore the most desirable.”

The pattern of non-Jewish support for Eliot against Jewish academic smears remains largely intact. When a cache of forgotten Eliot letters was discovered in the early 2000s, supporters pointed to apparently friendly exchanges with a number of Jews, including notorious figures like the original theorist and promoter of multiculturalism Horace Kallen, and the academic Franz Boas (who had been friends with Eliot since graduate school but ended their relationship in 1934 due to Eliot’s “anti-Semitic” comments in After Strange Gods).

None of it was enough to satisfy Eliot’s most ardent critic, with Anthony Julius (who despite his legal career has refused to leave this area of academic life) later attempting to silence his opponents by remarking that “Critics who excuse Eliot’s anti-Semitism, or worse, pretend that it does not exist, merely carry on his own work of contempt towards Jews.” In this, perhaps the ultimate smear, Julius accuses even the supporters of Eliot of being complicit in ‘anti-Semitism.’ Julius found himself seconded by Jewish academic Marjorie Perloff, who opined that, “However warmly Eliot may have felt about this or that Jewish friend or acquaintance…researches reveal that for the poet, Jews remain Jews first, individuals later.”

The purpose of the preceding case study has been to present a treatment of the psychology behind, and methods of, cultural deconstruction. Much is revealed, during the course of such an analysis, about “anti-Semitism” as it exists in the socio-cultural consciousness of strongly-identified Jews. Grasping such concepts and understandings are important because ideas are important. Ideas are crucial to both the creation and undoing of culture, and cultural memory. The battle for ideas is unceasing, and it continues, relentlessly, against a backdrop of elections, policy changes, economic shifts, and natural disasters.

While politics is crucial, we neglect the cultural war at our peril. To paraphrase the conclusion of my treatment of the campaign against Ezra Pound: Civilization, for all its greatness, is ultimately a fragile entity. It requires care, conservation, and occasional pruning. If our culture loses sight of its geniuses, we will be all the poorer for it — ideologically, spiritually, tactically, and culturally. We all have a duty to keep these figures and their work alive. Our ability to do so will ultimately determine whether there is life in our civilization yet, or whether we may be as Eliot’s ‘Hollow Men,’ our voices forever “quiet and meaningless.”

[1] A. Julius, T.S. Eliot, anti-Semitism, and Literary Form (London: Thames & Hudson, 2003), pp.10-11.

[2] Ibid, p.11.

[3] For this citation, and a more complete yet succinct survey of the correspondence of T.S. Eliot, see ‘Eliot’s Inferno: The Letters’ in Craig Raine, More Dynamite: Essays 1990-2012 (London: Atlantic Books, 2013).

[4] Ibid.

[5] See for example, L P Gartner, ‘Anglo-Jewry and the Jewish International Traffic in Prostitution, 1885 – 1914’, Association for Jewish Studies Review, vol. 7-8, 1982, pp. 129—178.

[6] A. Julius, T.S. Eliot, anti-Semitism, and Literary Form (London: Thames & Hudson, 2003), p.1.

[7] Ibid, p.11.

[8] Ibid, p.2.

[9] Ibid, p.5.

[10] Ibid, p.26.

[11] Ibid, p.21.

[12] Ibid, p.23.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid, p.24.

[15] Ibid, p.31.

[16] Ibid, p.25.

[17] Ibid, p.55.

[18] Ibid, p.56.

Comments are closed.