Bitter Harvest: A Brilliant Film on the Ukrainian Holodomor

“This particular film was extremely important to me, and it felt almost like a mission. I wanted to bring knowledge about the famine genocide, the Holodomor, to the Western world, and that’s why I did it.”

Ian Ihnatowycz, Bitter Harvest Producer

Bitter Harvest (2017) is a film inspired by the love and rediscovery of the writer Richard Bachynsky Hoover’s ethnic heritage. On a trip to the homeland of his Slavic ancestors he began to ruminate on how to capture the story of the Holodomor on film. With small acting parts in a variety of television series Bachynsky Hoover was learning the ropes of the film and entertainment industry. He went again to Kiev, investigating his family history. It was 2004 and the Orange Revolution was in full swing — he saw firsthand a Ukraine in the midst of upheaval. He learned that Western audiences had never seen the Holodomor dramatized on film — a dramatically different situation compared to that other genocide that has become a touchstone of Western Civilization and both a sword and a shield for Jewish and Israeli interests through endless promotion in the media. In 2008 he would return with a script, seeking financing for an English language period piece set during the Holodomor. He met with officials from the Ukrainian Government as well as various oligarchs. All of them turned him down. It was not until 2011 that the dream to make his movie finally caught a glimmer of hope when fellow Ukrainian Canadian investor Ian Ihnatowycz committed $21 million to the film.

Bitter Harvest (2017) is a film inspired by the love and rediscovery of the writer Richard Bachynsky Hoover’s ethnic heritage. On a trip to the homeland of his Slavic ancestors he began to ruminate on how to capture the story of the Holodomor on film. With small acting parts in a variety of television series Bachynsky Hoover was learning the ropes of the film and entertainment industry. He went again to Kiev, investigating his family history. It was 2004 and the Orange Revolution was in full swing — he saw firsthand a Ukraine in the midst of upheaval. He learned that Western audiences had never seen the Holodomor dramatized on film — a dramatically different situation compared to that other genocide that has become a touchstone of Western Civilization and both a sword and a shield for Jewish and Israeli interests through endless promotion in the media. In 2008 he would return with a script, seeking financing for an English language period piece set during the Holodomor. He met with officials from the Ukrainian Government as well as various oligarchs. All of them turned him down. It was not until 2011 that the dream to make his movie finally caught a glimmer of hope when fellow Ukrainian Canadian investor Ian Ihnatowycz committed $21 million to the film.

British actors Max Irons and Samantha Barks star as Yuri and Natalka, two childhood sweethearts from the same village. They marry young and soon their lives are thrown into the whirlwind of revolution and resistance that comes with annexation of the Ukraine by the Soviet Union and eventual famine by way of grain confiscation. Barry Pepper and Terence Stamp are crucial to the supporting cast as Yuri’s family. Pepper sports the classic Cossack khokol (also called oseledets in the Ukraine) haircut — a long lock of hair on the top or front of an otherwise completely shaven head. Tamer Hassan, an English actor of Turkish Cypriot descent, takes the role of the real life villain Sergei, a Soviet officer who enforced Stalin’s will with relentless brutality. Hassan is the only non-White cast member, and may in fact be the only non-White member of the film crew. With the exception of a few stunts the entirety of the film was shot in Ukraine with Ukrainian extras and crew — some of whom took part in the Euromaidan protests during their off hours while shooting from late 2013 to early 2014. In several interviews and promotional appearances for the film much of the cast — but most significantly Max Irons — expressed a slight sense of shame over their prior ignorance of the Holodomor and the need to raise awareness of this historical tragedy.

“You’ve got to look back hundreds of years from Catherine the Great, attempts have been made through Russification to dilute and separate the Ukrainian national identity. Despite all that and being stuck between a rock and a hard place — Europe and the former Soviet Union . . . despite that, the national identity is still intact. The energy to rise up out of those dire circumstances it so overwhelming.” Says Irons, of his impression of the Ukrainian people.

The film opens with a sweeping shot of golden fields of grain. Ukraine was the breadbasket of Europe and Director George Mendeluk (a German-born Canadian citizen of Ukrainian descent) showcases the beauty of its countryside. It was at the dawn of the days of Lenin when Yuri fell in love with his childhood sweetheart. Natalka was the girl he would grow up to marry, he told himself. In the first decade of their life they spent hours walking through the woods holding hands along the way to the river at the edge of their village. The agrarian life, warrior valor and the Orthodox faith defined the world view of their people. They loved the land, as the land was life. The rich and simple soul of the Ukrainian people could be seen when they worked their land, in their dances and at their dinners. It could be heard in their songs and felt when the wind sent a wave through bright fields of golden grain and acres of blooming sunflowers. We see a living land of beauty and tradition during a time of relative peace.

The serenity is first disrupted when a mounted Cossack (Terence Stamp) brings word of the success of the Bolshevik Revolution. The death of the Tsar brought freedom to their people, soon to be crushed by the Soviets. The film moves forward twenty years. Yuri leans against a tree as he finishes another sketch of a beautiful Slavic woman. Mykola, a poet — snatches the sketch away and chides his friend with revolutionary rhetoric, evangelizing on behalf of the government for his friend to give up his selfish desires. Ukraine is having its own cultural revolution and Mykola along with their musician friend Lubko try to convince Yuri to leave with them and join the artists flocking to Kiev. It was the 1920s and the Ukrainian Renaissance was hitting its peak. Painters, poets and musicians were turning their backs on Russian influences in the arts.

Yuri’s friends tell him to woo his childhood sweetheart. She plays hard to get but with persistence he gets her to pose for a portrait in the forest where they used to play. Natalka’s parents were unmarried when she was born and she carries the stigma of a bastard at a time when that mattered. Yuri doesn’t care. He’s in love. “We can face it together.” He promises her, disregarding any ostracism that could come from their coupling. He reassures her by encouraging her to ask the gods at a festival that evening.

“Night on the Eve of Ivan Kupala” by Henryk Siemiradzki

The unmarried young women of the village gather at the riverbank to float candlelit wreaths of flowers down the river and ask about their fortunes. Though never explained in the film, this festival is Ivan Kupala Day, taking place at the end of the first week of July — just after the summer solstice. The women try to divine their future (usually marriage prospects) by reading the pattern of the flower leaves on the river. The men dance and jump over the flames of bonfires to show bravery and faith. Although now dedicated to John the Baptist, the Ukrainians have been celebrating the solstice in this way long before they came in contact with the Orthodox Church. Natalka floats her wreath onto the water, asking if she’ll ever marry. The wreath drifts toward the mist hanging low on the river and sinks, extinguishing the flame. She fears that any love she and Yuri may have would be cursed by tragedy. Yuri is unrelenting and Natalka cannot resist. As the village drinks and dances into the night Yuri and Natalka make love.

Lenin dies. As Comrade Stalin seizes the reigns of the Soviet system he forms plans for the extreme collectivization of Ukrainian farmland. Soldiers from the Red Army trot in on requisitioned horses led by Sergei. Tamer Hassan gives one of the best performances of his life as Soviet officer Sergei. To say he suffered for the role is to put it mildly –—his horse stamped his foot when he absent-mindedly walked behind it, leaving what appeared in the X-ray to be a horseshoe shaped break. Ever the professional he had it wrapped and forced it back into his boot. They would later have to cut the boot off to remove it, due to swelling.

In his own research he found that his character — one of Stalin’s right hand enforcers — is a classic study in how to create a monster. He witnessed his mother executed in a church. He was raped by the priests and later became a ward of the state. Raised to be heartless, unforgiving and despising God in all representations, Sergei is the specter haunting Yuri’s homeland and village — a classic case of someone who rejects his culture because of ill treatment in his personal life. He demands the icon from the local church, knowing it would be the artifact most prized by the villagers. Sergei is a tyrant in service of an empire, who has never known love. In his final confrontation with the local priest the good Father peers into his soul. “Hell is the inability to love.” The last words of a man made brave through faith. Sergei executes him with a look of sheer contempt.

As local farm owners are evicted under threat of execution for the newly created crime of being a “kulak,” the Cossack blood stirs in the populace and sporadic cases of rebellion begin. After a brutal exchange with Soviet officers deep in the nearby wood leaves Sergei scarred, Yuri’s father hanged and his grandfather shot – though miraculously still alive, the grim reality that they are now an occupied territory is all too apparent. Yuri and Natalka marry. Sergei and his men trample Natalka’s mother as they gallop down the dirt road, leaving her bedridden. With his friends leaving for Kiev, Yuri’s grandfather castigates them for being cowards. He resisted Lenin and the Tsar before him. Where in this new age of progress and machines were the warriors of God his people had always strived to be? “He’s not like me,” the patriarch tells Yuri’s mother. “And he’s nothing like his father!” These words, spoken in anger, cut Yuri to the bone.

Stalin swears not to make the “mistakes” of his predecessor. He demands state confiscation of 90% of the grain, scoffing at the apparatchiks who insist this will cause catastrophic deaths in the region. “Who on earth will know?” He replies with a cruel smirk. He sets his tea on an American newspaper. The headline reads “Food shortages, but Ukraine not starving. All large cities have food. Foreign observers don’t predict a disaster.” As Michelle Malkin, Ann Coulter, Pat Buchanan and other writers syndicated on Vdare.com have sought to remind us, the refusal to report on the massive deaths by starvation was all too prevalent by journalists fawning over the communist super-state. Chief among Stalin’s henchman-in-print was Walter Duranty, who authored no less than 13 articles covering up the genocide in the USSR’s vassal state, winning Duranty a Pulitzer Prize for his efforts. The New York Times, for their part, admits the deception. Though they claim they do not have the prize in their possession, other Times writers have discredited Duranty. The Pulitzer Board? Demonstrating a monstrous lack of journalistic integrity, they refuse to revoke the 1932 award, claiming it is not a clear case of deception, making them just as politically biased as the Nobel Peace Prize and the MacArthur genius awards.

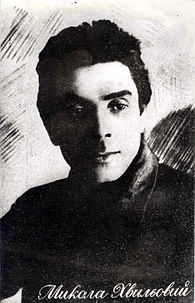

With the inability to prosper and famine beginning to creep across their country, Yuri joins his friends in Kiev. Mykola, the poet, welcomes him with open arms. Mykola is yet another character based on real life literary figure Mykola Khvylovy. The 1920s was the birth of the Ukrainian Renaissance, ended abruptly by the Holodomor. During Ukraine’s cultural flowering Mykola advocated that Ukrainians look to Western Europe for inspiration to free themselves from Russian social influence. Initially inspired by the ideals of communism, Mykola was a true believer who thought that Marxism and Soviet reforms would bring greater prosperity to his people, only to become disillusioned as he learned that all Socialist States of the Union existed only to serve the interests of Moscow and chiefly, the whims of Stalin and his henchmen. In protest of the mass arrest of his fellow artisans and literati, he committed suicide in his Kiev apartment with his friends present. However, this is not a spoiler. The film takes artistic license and weaves his death into the development of the plot and its main characters. His unpublished works were confiscated by the authorities after his death.

Mykola Khvylovy (1893–1933)

The portrait of Yuri’s trip to the city and experience as a factory worker in Kiev leaves little to be desired. As loyal party members dine by the fireplace that once warmed Grand Duchess Anastasia, emaciated Ukrainians rot in the alleyways of Kiev. Often repeated is the party line: “There is no famine. Only a food shortage. There is no starving. Only widespread malnutrition.”

Yet still the people were not broken. Many throughout the countryside were rising up. Grain quotas rise. The locals resort to banditry for the sake of self-preservation. Natalka’s mother passes away. With the end of one life comes the blossoming of another. Her letter tells her husband that their love endures. She’s going to have his child. Eventually he applies and is accepted to art school where he learns of Western artists. An eccentric professor encourages him to explore his subconscious. His ideas seem truly revolutionary to the aspiring and talented young artist. Tearing away the curtain to the studio he commands that “as an artist you must find the truth. With light.”

This aphorism, made heavy by the events unfolding around them is another example of scriptwriter Richard Bachynsky Hoover’s talents. Much of the dialogue in the movie is deep and rich, although viewers may not realize to what degree until they watch it again.

Therein lies more of the superb cultural value of this film. As a romantic drama replete with such free flowing metaphor and aphorism, most viewers will not only want to own a copy, but will re-watch it several times. Given the emphasis on the enduring love between Natalka and Yuri amid the despair of a genocide, romantics of both sexes will have a very positive response to this movie.

With Yuri’s professor exiled to Siberia, he is forced to leave the university. His work is considered too reactionary. He learns of the death of his friend Mykola,. At the wake, the band begins to play. The dancing starts. Not more than a minute into the song the Soviet commanding officer sitting at a corner table springs to his feet and throws the dancer across the floor. He curses the folk music and demands a Soviet song in praise of Stalin. They began to kick and punch the musicians. Yuri has had enough. Already mourning the loss of one dead friend, he is adamant not to lose any other Ukrainians to the iron heel of Soviet totalitarianism. It turns into a battle royale. Tables overturn, heads bang against support beams. A knife comes out. A knife goes in. One dead soldier later and Yuri is on his way to the gulag.

He barely survives a trip before the firing squad with other prisoners when the commanding officer does not give the order to shoot. It seems that the officer is enthralled by his power of life and death over his prisoners, so he rehearses execution with prisoners, keeping them scared and compliant. The prisoners try to please their guards and give little resistance when ordered to perform a task. ISIS uses the same tactic now. As Yuri struggles in captivity, the women of his village go on the offensive. Each must use their God-given talents to fight their way through their oppressors, dreaming to reunite with their loved ones.

What could inspire anyone amid so much death? What keeps you alive through despair of such a magnitude? Love? Faith? Perhaps. An unbreakable will to seek justice? As the film fades to black after the climax, messages detailing the devastation of the Holodomor appear. Light enters the background as if the sun rose on a dark gray morning. A forest of death appears. Bodies strewn along the ground and up an embankment — heads and feet sticking out from behind trees. The camera slowly pans up to reveal the rest of this black and white photograph. The horizon is distant. Beyond so much horror, there is light.

Bitter Harvest does not in any way compare to Hollywood’s holocaust industry. And it’s no surprise that an article at CounterPunch condemns it as fascist propaganda. It’s by an apologist for Soviet communism who, for example, also rejects Khrushchev’s speech describing the crimes of Stalin and Beria as “provably false” and would be horrified at any departure from the official Holocaust narrative. He has also written a book, Blood Lies; The Evidence that Every Accusation against Joseph Stalin and the Soviet Union in Timothy Snyder’s Bloodlands Is False.

We must never forget that the communist-sympathizing left would commit similar crimes again if they had the power.

Don’t just rent it. . . buy it.

Comments are closed.