The Tale of John Kasper

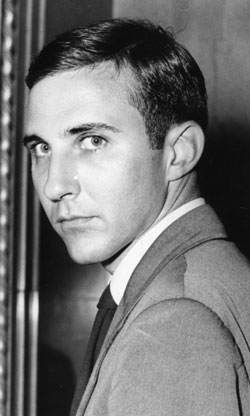

John Kasper

In 2007, I wrote the article on the white activist John Kasper (1929–1998) that will follow these prefatory remarks. I remember it well, because it was the very first writing I did for a personal website I had just set up and still maintain—http://robertsgriffin.com/. I have the sense that this Kasper article has been read by few people over the years, though six months or so after I posted it, a Wikipedia entry on Kasper was created that drew heavily on what I wrote. I felt good about that.

The Kasper writing came to mind this past week (it’s December of 2017) because I happened upon a reference on the internet to a new book about Kasper—John Kasper and Ezra Pound: Saving the Republic (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017) by Alec Marsh. I was surprised to see it: I hadn’t imagined that Kasper was a big enough deal to warrant a book about him, but there it was. It isn’t in the university or public library around where I live, and it’s pricey, around $40 for a hardback, $30 for a Kindle. After some soul-searching, I bit the bullet and bought the Kindle. If you decide to get the book, you don’t have to spend that kind of money for it. If a library doesn’t have it in its collection, it can obtain it for you through interlibrary loan. I didn’t want to wait for that process to play out, thus the Visa card payment.

The Kasper writing came to mind this past week (it’s December of 2017) because I happened upon a reference on the internet to a new book about Kasper—John Kasper and Ezra Pound: Saving the Republic (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017) by Alec Marsh. I was surprised to see it: I hadn’t imagined that Kasper was a big enough deal to warrant a book about him, but there it was. It isn’t in the university or public library around where I live, and it’s pricey, around $40 for a hardback, $30 for a Kindle. After some soul-searching, I bit the bullet and bought the Kindle. If you decide to get the book, you don’t have to spend that kind of money for it. If a library doesn’t have it in its collection, it can obtain it for you through interlibrary loan. I didn’t want to wait for that process to play out, thus the Visa card payment.

Author Alec Marsh is an English professor at Muhlenberg College in Pennsylvania with a particular interest in Ezra Pound, one of the twentieth century’s preeminent poets and most influential literary personages. Not only did Pound — born in Idaho, lived in Paris, London, Italy, and the U.S., died in Italy — produce great art himself, he inspired and mentored great artists, among them T. S. Eliot and Ernest Hemingway. Pound was highly controversial personally, as he was tabbed a fascist and anti-Semite. After reading the Marsh book, it can be said that, for better or worse — most would say worse, I say better — he inspired and mentored young (in his twenties), American, New Jersey childhood, Catholic upbringing, Columbia University, John Kasper.

I respect Marsh’s book very much and recommend it: it’s impressively researched, and it’s even-handed; it’s not a hatchet job on Pound or Kasper as a racist, anti-Semitic nut case, which for many would have been tempting. I didn’t pick up the patronizing and virtue signaling that characterizes so much academic “scholarship” these days. Good for Professor Marsh.

Marsh draws heavily on letters Kasper wrote to Pound which are collected in the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University. (Pound’s letters to Kasper didn’t survive).

These letters, often long and informative, sometimes embarrassingly fulsome and worshipful, sometimes gossipy, sometimes mere business transactions revealing records of books (often anti-Semitic tracts) bought by the poet, offer fascinating views of the American Right in the 1950s.

Marsh takes John Kasper seriously:

Kasper was more than a rabble rouser; he was a serious transmitter of Pound’s ideas who imagined himself as the successor to James Laughlin as Pound’s publisher. Pound’s idiosyncratic Confucianist, Fascist Jeffersonianism, and Kasper’s home-grown Christian anti-Semitism fed off each other, influencing Pound’s great poems and Kasper’s “Southern strategy.” . . . From 1956 until 1964, when he represented the National States Rights Party (NSRP) as their candidate for president of the United States, Kasper was a major player in the neo-Confederate underground that actively resisted efforts by the federal government to enforce the racial integration of schools across the South. Through his friend and associate Admiral John Crommelin, Kasper knew and worked closely with everyone in the resistance movement, including Asa “Ace” Carter, J. B. Stoner, Bill Hendrix (head of the Southern Knights of the Ku Klux Klan), George Bright (charged in the Atlanta synagogue bombing), and Ed Fields, founder, along with Kasper and others, of the NSRP and active into the twenty-first century.

I found Marsh’s account of Kasper’s mindset and activities informative and fascinating. In my article on Kasper, I focused narrowly on his efforts during a single week in 1956 to thwart school integration in Clinton, Tennessee. Marsh fleshed out for me who Kasper was and what he did beyond Clinton—at least in the ‘50s. A big reason I got the Marsh book was to find out what happened to Kasper after 1964. Unfortunately, Marsh wasn’t helpful in this regard. I assumed there’d be something about what Kasper did from his mid-30s until his death at 68, but the book seemed to suddenly quit. Marsh noted in an early chapter that Kasper died of an accidental drowning. That’s it. There is nothing about Kasper’s presidential run in 1964. Indeed, he received a miniscule number of votes, but how many people do you know who have run for president? But then again, Professor Marsh was under no obligation to satisfy my curiosity. As the title of his book indicates, his book is about Kasper and Pound, and that connection was a ‘50s phenomenon.

Reading about what went on back then, it struck me how different things are now with the internet and social media. These people wrote lengthy letters back and forth (when’s the last time you got a personal letter, or wrote one?). They ran things off on small printing presses. Public discourse was the province of three television networks, Hollywood, a small number of New York publishing houses and magazines, and a few big newspapers, particularly The New York Times. No web sites, no Twitter—only what we now call the mainstream media. The mainstream — or better, onlystream — media did all the talking, and if they didn’t like you, to the extent they dealt with you at all, they hammered you and there was nothing to counteract that. They made Pound and Kasper, especially Kasper, look like demons and fools. I came away from the Marsh book with a heightened appreciation for my personal web site, social media, and, indeed, The Occidental Observer.

I was concerned that the Marsh book would undercut the veracity of what I wrote about Kasper a decade ago, but I’ve decided that the article holds up well, and I feel comfortable passing it on to you in this context. So here it is, what I wrote about John Kasper in 2007.

* * *

When reading a biography of the Ezra Pound, one of the premier poets of the twentieth century, references to a man named John Kasper caught my eye.1 According to Pound’s biographer, in 1950 Kasper, a 21-year-old Columbia University student, wrote Pound, who was living in Washington, D.C., an adulatory letter saying that he had just written a term paper that compared Pound favorably to the great German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. Pound wrote back, and this began weekly correspondence between the two men. Kasper’s letters to Pound are contained in the Yale and Indiana University libraries (evidently Kasper didn’t keep Pound’s letters) and are characterized by Pound’s biographer as “extraordinary.”

After Columbia, Pound’s biographer reports, Kasper opened a bookstore in the Greenwich Village area of New York City that stocked Pound’s work. Eventually Kasper moved from New York City to Washington, primarily motivated, it appears, by the desire to be around Pound, whom he greatly admired. Kasper and Pound became quite close, to the point that Kasper has been described as a protégé of Pound’s. In any case, it seems clear that Kasper was strongly influenced by Pound’s political and social ideas: Pound was a white racial advocate, which included antagonism toward Jews. Kasper started up a second bookstore in Washington and, with a partner, set up a publishing company that published some of Pound’s poetry as well as that of other poets, among them, Charles Olson.

Immediately following the 1954 Supreme Court decision in the Brown v. Board of Education case outlawing racially segregated schools, Kasper organized the Seaboard White Citizens Council. The motto of Kasper’s organization was “Honor-Pride-Fight: Save the White.” Its avowed purpose was to prevent school integration in Washington. As it turned out, it wasn’t in Washington that Kasper fought school integration but rather in Tennessee. Pound’s biographer refers to the “dramatic events” in the town of Clinton, Tennessee around the integration of Clinton High School, and quotes an historian as saying that Kasper “had a large hand in the violence that plagued Tennessee in 1956 and 1957.”

My curiosity was piqued. Who’s this John Kasper? I asked myself? I’d been interested for the last decade in white racial consciousness and advocacy — which is what drew me to the Pound reading in the first place — but I’d never heard of John Kasper. Extraordinary letters? Dramatic events at Clinton High School? Violence in Tennessee in 1956 and ‘57? I knew about the trouble around the integration of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957—in fact, I’d written about it—but I didn’t know anything about what went on in Tennessee. The Pound biography referred to something Kasper had written called “Segregation or Death”—I’d never heard of it.

It hit me that, much less Kasper, I didn’t know about any white racial activist who had traveled to the South to oppose desegregation. The only people I had heard of went to the South in support of black civil rights—Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, who in 1964 were murdered in Mississippi, come to mind. Without really thinking about it, I just assumed that no Northerner would go to the South in support of segregation. Yet, evidently at least one person did, this John Kasper. That realization shook my basic sense of the history of those years that I had taken in from school and the media and held onto despite a good amount of experience and study this past decade that should have brought it into question, that the only people who opposed the black civil rights movement in the 1950s, desegregation of the schools included, were behind-the-times Southern locals.

I decided to look into this John Kasper and what went on in Tennessee back then. This is a report of what I’ve been able to find out and the meaning I’ve given it.2

Clinton High School, in Clinton, Tennessee, which is just outside Knoxville, was scheduled to open for the new school year on Monday, August 27th, 1956. The previous year, the Clinton school board had announced its intention to “comply with any and all court mandates.” Clinton High School would be one of the first schools to be desegregated following the Brown decision. Virtually all whites in Clinton were opposed to racial mixing in the school, but they were resigned to the fact that it was going to happen.

Saturday afternoon, August 25th, 26-year-old John Kasper arrived in town in his battered old car from his home in Washington, D.C. Kasper was tall and clean-cut and wore a suit and tie. He immediately began buttonholing people on the street and going door to door handing out literature he’d put together on his organization, the Seaboard White Citizens Council—which I suspect was just him, really. He talked about what was going to happen on Monday at the high school and how it wasn’t right and that the people in town shouldn’t just passively go along with what had been imposed on them from afar. He said he was going to give a speech the next afternoon, Sunday, in front of the courthouse and invited people to attend and to tell their friends. That night, he slept in his car.

Sunday afternoon, a smattering of people showed up for Kasper’s speech. He was dressed in his suit and tie and was well spoken. He told those in attendance that integration was a leftist plot and would undermine the white race. They needed to stop school integration in Clinton. “We’re fighting, and you must fight with us.” He told his audience that “people are superior to courts,” and urged them to picket the high school, and he encouraged students to stay away from classes. A Clinton resident who was in the audience that day recalls, “What I remember most about him is that he was so dedicated, so sincere about a project that struck me as hopeless.”

Later that same day, Sunday, Clinton town officials met to decide what to do about Kasper. They tried to persuade him to leave town, and when that failed they had him arrested for vagrancy and inciting a riot and put in jail, where he spent the night.

Monday, the first day of school, with Kasper behind bars, a crowd of about fifty people gathered outside the high school to protest the enrollment of blacks for the first time. However, desegregation went off essentially without a hitch.

Tuesday, Kasper was tried and his case dismissed for want of evidence. He immediately went to the high school and told the principal to “run the Negroes off or resign.” He distributed signs he had put together demanding the principal’s resignation. He organized a picket line around the high school and recruited some white teenagers into what he called the Junior White Citizens Council. That night he gave a fiery speech to several hundred in the courthouse square.

Wednesday, a crowd of over 100 protesting whites—a mob, the media called them —gathered outside the high school. There were walkouts by white students, and white students chased and attacked black students. Out of fear of the protestors, or mob, whatever to call them, a number of black students slipped out of the back door of the school.

That night, another Kasper speech. This time, the crowd was 1,000. His speech was interrupted by a federal marshal, who served him with a court order temporarily restraining him from interfering with school integration and notifying him that there would be a hearing the next day on a permanent injunction. Kasper went right back to his speech. A member of the audience that night recalls that when Kasper spoke to the crowd, “he had eyes like you’d never forget.”

Thursday, with Kasper tied up at the hearing —which turned out to be a trial, actually — a crowd of 300 milled around the high school and shouted epithets and hurled tomatoes and stones at black students as they entered and left the school. A judge found Kasper guilty of contempt of a court order—there was no jury. When the judge asked him if he had anything to say before sentencing, Kasper replied, “Stop the integration of Clinton High School.” The judge sentenced him to a year in prison. Before being taken off to jail, Kasper told the press, “Woe to those whose only right is their power. The wild grass will grow over their dead bodies.”

That night, the speeches were from representatives of the Tennessee Federation for Constitutional Government, a white advocacy organization that had come to Clinton after hearing about what going on. Now the crowd was 1,500.

Friday evening all hell broke loose. Asa (Ace) Carter, a white organizer and crowd-stirring orator who had come to town, gave a speech to the 2,000 in attendance attacking the Supreme Court, the NAACP, and the “carpetbagging judge” that had put Kasper in jail. The crowd began shouting “We want Kasper!” A “rioting mob,” as the media called it, marched to the mayor’s house—he was friendly to school integration — and threatened to dynamite it. Traffic was blocked on the major road running through Clinton and cars with blacks were stopped and tilted and windshields were smashed and air was let out of tires. This went on until 1:00 a.m., with no arrests.

Saturday, September 1st, the Clinton board of alderman declared a state of emergency in Clinton. A 47-man auxiliary police force was formed and armed with shotguns and tear gas. The rally that night—3,000 in attendance — was sponsored by five white organizations that had gotten involved when they found out what was happening: the Tennessee Federation for Constitutional Government; the Pro-Southerners; the White Citizens Councils; the Tennessee Society to Maintain Segregation; and the States’ Rights Council of Tennessee. The newly formed posse, as the news accounts called it, marched in line until it came face-to-face with the whites who had gathered that night and told the crowd to disperse. The whites didn’t comply and there was a standoff. Three tear gas grenades exploded in the middle of the crowd, and it started to break up. Three more grenades got the job done.

The next day, Sunday, September 2nd, into Clinton came 600 battle-equipped National Guardsman, along with seven M-41 tanks and three armored personnel carriers. The nightly rally was attempted again, but the crowd of 1,000 was dispersed by two platoons of guardsmen with fixed bayonets.

The week’s remarkable events in Clinton drew worldwide media coverage. “Officers and school officials alike,” the local newspaper reported, “blame most of the trouble on a 26-year-old Washington man named John Kasper.”

On Monday, the commander of the National Guard, General Henry, ordered public address systems and outdoor public speaking prohibited in Clinton, and pretty much things cooled down in town for the next few days.

Thursday, a judge granted Kasper the right to bail and issued him a permanent injunction against any further interference with desegregation. Two Clinton citizens put up the $10,000 bond and Kasper was released. A couple of weeks later he was back in jail briefly and released on another bond for a Tennessee state charge of sedition and inciting a riot, with the trial date set for November. The November trial lasted two weeks. Kasper supporters packed the courtroom. On November 20th, amid cheers, Kasper was acquitted. On the courthouse steps, he announced he would continue his fight against school integration.

Kasper toured the South giving speeches. His message highlighted the dangers of miscegenation and included an anti-Jewish theme, as he declared the integration effort to be part of Jews’ “fanatical effort to subvert existing Gentile order everywhere.” He told a Birmingham, Alabama audience, “I’m a rabble-rouser, a trouble-maker. Some of us may die, I may die. I’m not through up there [in Tennessee]. It may mean going back to jail, but I’m going back to fight. We went as far as we could legally. Now is the time to fight, even if it involves bloodshed.” On another occasion, he declared, “I say that integration can be reversed. It has got to be a pressure like a stick of dynamite you throw in their laps and let them catch it, and then they can do what they want with it, but let them worry about it.”

Over the next year, Kasper was in and out of jails in Clinton, Nashville, and Knoxville. He was jailed for vagrancy, loitering, disorderly conduct, inciting a riot, and for “unlawful acts of trespass, boycott, picket, and interference with the free operation of the schools.” “I’ll never desert the white race in Tennessee until the outcome of our struggle is crystal clear and spells victory over the race mongrelizers,” he declared. “I have been interested all my life in the purity of the races. I do not hate Negroes, but I believe that for the progress of the white and Negro races this is best accomplished by segregated institutions.”

Shortly after midnight on the opening day of school in September of 1957, a dynamite blast demolished a wing of a newly integrated elementary school in Nashville. Kasper, who had talked of “the shotgun, dynamite, and rope,” was suspected of the crime, but no evidence linking him, or anyone else, to the bombing was ever found. He was also a suspect in a series of synagogue bombings in the South, but was not charged in those crimes.

Late in 1957, Kasper was convicted of the federal charge of conspiracy and spent eight months in federal prisons in Florida and Georgia. Kasper referred to himself as a “political prisoner” and said that his federal imprisonment had been the result of “jewspaper lies.” At a “welcome out” party when released from the penitentiary in Atlanta, he declared that both the Republicans and Democrats were committed to integration and the destruction of the white race, and that the country needed a third party. “The answer to the integration problem,” he asserted, “lies in a return to Constitutionalism.” He then went to Nashville for a trial on riot agitation in that city, for which he spent six months in the workhouse.

As for Clinton, there were sporadic demonstrations and protests—including a return visit and speech from Kasper—and random violence. The Tennessee Federation for Constitutional Government tried to halt desegregation in Clinton by state court injunction. The Tennessee State Supreme Court ruled against that petition, declaring “the question is fully foreclosed by the United States Supreme Court.” Early on a Sunday morning in April of 1959, three dynamite blasts reduced Clinton High School to rubble. No one was hurt due to the timing of the bombing, and the perpetrators were never apprehended.

The media coverage throughout this period painted a very negative picture of Kasper and the cause he represented. An example, a 1957 Time magazine article defined the issue involving Kasper as “racist passion on the one hand and appeal to law and order on the other.” It depicted Kasper as an “interloper,” “meddling,” “a preening cock,” “an emotional idiot,” and a “screwball,” and in order to discredit him, trafficked in the rumor that when he lived in New York he “kept company with a Negro girl.”3

A recent Knoxville newspaper account looking back on the events in Clinton refers to Kasper’s physical appearance as “rodent-like.” I was struck by that characterization because it was reminiscent of something that I had just read in a biography of ballet impresario Lincoln Kirstein. In 1965, Kirstein, a New Yorker, traveled to Selma, Alabama to participate in the black grievance march from Selma to the state capital in Montgomery. Kirstein was quoted as describing disapproving whites along the march route as “rat-faced” (not far from “rodent-like”), as well as “snake-faced,” “fox-faced,” and “pig-faced.”

In 1964, Kasper was on the ballot as the presidential candidate of the National States Rights Party. He ran unsuccessfully for state representative in Tennessee. I wasn’t able to find out much about what happened to him from there on, and nothing I feel any degree of certainty about. I think he lived in Nashville until 1967 and then moved back up north and dropped out of public activity. He married and had children and worked a series of office jobs. Social security records indicate that he died in 1998 at the age of 68.

It took some doing, but I was able to find the writing that was mentioned in the Pound biography, “Segregation or Death.” It was an article by Kasper in the May 1957 Virginia Spectator magazine. It was part of a “Jim Crow” theme issue that was compiled by the novelist William Faulkner. Around this same time, Kasper produced a pamphlet with this same title and essentially the same content for his Seaboard White Citizens Council that I was also able to obtain. Excerpts from the article:

Any man who fails to distinguish between this thing and that thing may be called ignorant and lacking in reverence. Distinctions come from awareness; they come from respect for intelligence and the process of intelligence.

Only an imbecile or a liar will deny the validity of race, the separate and distinct races of mankind.

He who denies race also denies the important qualities of individuals, as both race and individuality are qualities of the blood, not language, environment, or common living space. Both individuals and race are products of Nature. He who denies race denies the power of intelligence, imagination, and creative power in the individual; perhaps most important: individual courage.

We affirm that all movement in history, the historical process, results from race and personal character. In the flow and surge of mankind there is only the inborn natures of men, and the devotion that they give to the inborn nature. War, economic struggle, art, and benevolent thought are only expressions of the inborn nature of man.

The penalty exacted by Nature for ignoring abundant life and continuing generations, carefully delineated along fixed geographical and racial limits, is eventual sterility, physical weakness and sloth, and finally effacement from life’s intricate patterns.

While denying race in one breath, the race fanatics are helping themselves to the loot and bounty of the thousand-year-old civilizations of all races and nationalities to benefit exclusively their own race, the Jewish.

We will not yield segregation as the only known means, proven by all historical evidence, for keeping blood-lines pure, races vital, individuals self-respecting, and diverse people living in mutual harmony and understanding. We will not fail in this struggle, even in death.

During that tumultuous first week in Clinton, one of the speakers at an evening rally that Kasper couldn’t attend because he was in jail was retired admiral John Crommelin, who had traveled from Alabama to be there. “You may not see it,” Crommelin told the crowd, “but someday a statue will be erected on this courthouse lawn to John Kasper.”

Of course, no statue of John Kasper has been erected in Clinton or anywhere else. Kasper was vilified and punished at the time, and then discarded down the memory hole of history—very few in our time know about him and what he did a half century ago. As we conventionally look at things, the person in the audience listening to Kasper’s speech that first night in Clinton was right: his cause was hopeless, and he failed. John Kasper was no match for the government and the military and the media. Clinton High school was desegregated, as were the other schools in East Tennessee. The vast majority of people think that was a good thing, and those who know about him think that John Kasper was a misguided and foolish and bad man. I’ll let readers of this writing make their own call about that.

What I’ll offer here is that, whatever the merits of Kasper’s outlook and actions, he was in significant ways an admirable man in those years.

John Kasper put himself out there, he acted, he took risks. Ezra Pound said about Kasper, “Well, at least he’s a man of action, and doesn’t sit around looking at his navel.” Just 26-years-old, John Kasper packed his suit and the literature he had printed up and got in his car and drove alone to Clinton, Tennessee. He could have stayed home, but he didn’t stay home. That’s admirable.

I define integrity as living in alignment with your most cherished beliefs and engaging what you consider to be the most important things. John Kasper had integrity. That’s admirable.

To me, courage is doing what is right as you see it, whatever the consequences and in spite of apprehension and fear. Kasper had to know that he was going to get attacked hard for what he was about to do, and he did get attacked hard, and he had to be scared, and yet he went forward anyway. John Kasper had courage. That’s admirable.

I’m taken by the last sentence in the excerpts from Kasper’s writing in “Segregation or Death” I quoted above: “We will not fail in this struggle, even in death.” He used the word “we”; to him, this wasn’t just his struggle. And when he talked about being successful “even in death,” I took that to mean that he viewed the struggle he had taken on as not ending when he was worn out or ground down —with his spiritual death —or with his literal death. Others would follow him, and still others would follow them. The struggle for the existence and wellbeing of white people was, in Kasper’s eyes, an historical struggle, a struggle for the ages. Seeing oneself as part of something larger than one’s own mortal existence is admirable.

On May and June, 2007, whites gathered in Knoxville to protest the savage rape, mutilation, and murder of two young white people by blacks and the media’s underreporting of this particular crime and black-on-white violent crime generally. The Knoxville rallies took place just a few miles from the events in Clinton a half-century earlier. One of the Knoxville protestors at the May rally carried a sign that said “Diversity=Death,” which reminded me of “Segregation or Death.” I wondered how many people gathered in Knoxville, if any, knew about what had taken place nearby those many years ago, or about John Kasper, who had died nine years before.

From every source, insistent messages come through to white people who care about the fate of their race: “History isn’t about you.” “You are an anomaly.” “Nothing preceded you and nothing will follow you.” “Everything you care about has been resolved, so keep quiet and get with the program.” But none of that is true, and knowing about Kasper, and others like him, will show that. Everything hasn’t been resolved, and racially conscious whites are not going to keep quiet, and they are not going to go along with the program. And they won’t fail, even in death.

Notes

- E. Fuller Torrey, The Roots of Treason: Ezra Pound and the Secrets of St. Elizabeths (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1984).

- Two major sources of the account that follows: Benjamin Muse, Ten Years of Prelude: The Story of Integration Since the Supreme Court’s 1954 Decision (New York: Viking Press, 1964); and Jack Neely, “The Poet, the Bookseller, and the Clinton Riots,” Metro Pulse (a Knoxville, Tennessee weekly newspaper), month and day uncertain, 2006.

- “Victory for Little Bob,” Time, August 25, 1957.

- John Kasper, “Segregation or Death,” Virginia Spectator, May 1957.

Comments are closed.