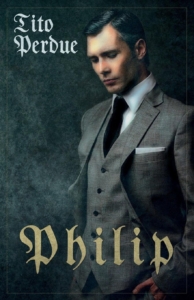

Doubling Down on the Art of Dying Review of Tito Perdue’s novel, “Philip”

Philip

Tito Perdue

Arktos, 2017

Each autobiographical novel conveys a writer’s hidden quest for his cryptic double. As a rule, the double always resides in the author’s close proximity. In the same vein a reader will fall in love with the author’s novel if he can detect in it bits and pieces of his own strayed-away double. In all  of his novels Tito Perdue’s lead character, Lee Pefley, mirrors not just the author’s own feelings of gloom and doom, but also bears witness of what he sees as the unstoppable death of the West. Although the lead character is Purdue’s own double, he wisely avoids the personal pronouns ‘me’ or ‘I’, never indulging in his own hidden ego trips. Instead, Purdue uses a gallery of characters from everyday life—characters that an average reader can easily identify with. Surprisingly, in his latest novel, Philip, we do not meet much of Purdue’s double, i.e. his doppelganger Lee Pefley, although, toward the end of the novel, Lee does briefly show up, his main role being to berate Philip on ars moriendi—the art of dying.

of his novels Tito Perdue’s lead character, Lee Pefley, mirrors not just the author’s own feelings of gloom and doom, but also bears witness of what he sees as the unstoppable death of the West. Although the lead character is Purdue’s own double, he wisely avoids the personal pronouns ‘me’ or ‘I’, never indulging in his own hidden ego trips. Instead, Purdue uses a gallery of characters from everyday life—characters that an average reader can easily identify with. Surprisingly, in his latest novel, Philip, we do not meet much of Purdue’s double, i.e. his doppelganger Lee Pefley, although, toward the end of the novel, Lee does briefly show up, his main role being to berate Philip on ars moriendi—the art of dying.

The hero of the novel, Philip, who is past the age of 30, is a well-educated, well-groomed, and a good-looking Southerner. He holds the enviable position of a supervisor in a subdivision of a company dealing with international trade. Most of Philip’s employees are women who swoon each time he walks by their cubicles and who would be willing to strip naked in public in order to secure a romance with their boss. Philip, however, is not a womanizer; nor is he, despite his Southern charm, a sex-obsessed macho man. He is not after women; they are after him. Philip is quite content, however, with his choice—a rather aged New York hooker well-versed in the art of caring for his biological needs and who never ever bothers to investigate his hidden transcendental thoughts.

Philip also goes by the name of “Linguist.” And it’s no accident that he chose this fancy nickname. He gets his high more from studying the syntax of Latin than reveling in the endtimes of multiracial America. Nor is Philip a careerist intent on moving up the ladder, nor does he seek to become a wealthy businessman. His charming smile—a smile that disarms all the women and provides him with access to lofty spheres of the New York jet set—is essentially a Southern disguise for his world weariness, or what the German late romanticists called Weltmüdigkeit, or “life fatigue.” Philip’s mind is never focused on the tons of invoices and business transactions generated by his company; instead, his mind ascends to the metaphysical stratospheres of his passing being, now being tossed around in the flow of time in which Philip tries to discern the meaning of life in the belly of the beast—the beast that is otherwise known as New York City.

In fact, the novel reads like a sequel to examples from previous Perdue novels featuring Lee Pefley’s contemplations on ars moriendi in the dying South—and by detour in the dying West, although Perdue doesn’t shy away from having his Philip occasionally refer to some life-inspiring and palpable objects, such as nice pieces of female butts obtrusively surrounding him at his New York office. The mixture of the hyperreal and the grotesque makes the novel quite intriguing, a skill Perdue has always excelled at in all of his novels.

Philip possesses an uncanny ability to decipher different racial phenotypes from a distance of 200 feet when taking strolls down Sixth Avenue. He can tell with precision the pedigree of each biped on a New York sidewalk—Jews, Negroes, Nordics, lesbians, and even Southern country girls who were once blinded by the tempting glitz of New York, only to get stranded thereafter in a promiscuous hellhole. Above all, Philip is a first-class master in preemptively deciphering the hidden motives of the people wishing to hurt him or cozy up to him—which means more or less same thing to him.

Finally, Philp decides to make an executive decision: he withdraws his fairly substantial savings from his bank account, dumps his job of a supervisor, and moves back to rural Tennessee. A big disappointment though awaits him there however. Tennessee, along with the rest of the West, is a dying place too, where the reader encounters time and again the travesty of what the South, or for that matter the whole of the West, once was or was meant to be. Philip’s mental travelogue starts anew; lots of young White executives he once befriended back in New York had faked their immortality by working out daily in a nearby gym. Other would-be immortals he knew of lived in self-denial by embarking on various vegan trips, or cutting coke, or taking different pills—red, white, green, black ones—you name it. Philip decides to choose his own shortcut to eternity: he cuts his veins….

****

The meaning of this novel will depend on a reader’s own interpretation of it, or for that matter on the whims of some infamous liberal-minded literary critic. A student in comparative literature will also try to have his or her own way: he, or she may be tempted to rank Philip according to literary genres that best suit his or her college requirement. Alas, Philip defies classification. Although plagued by life fatigue, Philip is not a medical case deserving hospital treatment. Neither does Philip fit into a category like French symbolist authors whose heroes keep whining about mal de vivre, or who complain ceaselessly about their deep-seated ennui. In fact Philip’s charming smile is not a fake grimace; it denotes a man who expects not just to be entertained, but who knows how to be a classy entertainer himself.

The problem with Philip is of a different and far more serious nature; he is a superfluous man of the Ivan Turgenev type, a homme de trop, who does not like to be pestered by unnecessary chores, such as cooking, tying his shoe laces, or even breathing air. For Philip, life is an accidental nuisance which merits to be terminated quickly, or in his own words:

..Why must he brush his teeth on a regular schedule, or wear shoes, or, for that matter, why should he have been decanted into such an inefficient body in the first place? He despised his daily life and yet, strangely, loved it in retrospect. And in short, nothing chagrined him more than that he was just a human man.

Some themes in this passage—a passage in which Philip tinkers with his existentialist brooding—are reminiscent of the characters depicted by the early leftist existentialist authors Albert Camus and Jean P. Sartre in their novels The Stranger or Nausea respectively. In addition, one could enumerate at least two dozen nationalist — or let’s call them “fascist”, “traditionalist”, or “antimodern” authors — in which Philip’s avatar and his alter ego Lee Pefley keep popping up, albeit under a different shape and confronted with a serious political choice. Although Philip never claims any political allegiance, his life-weariness is substantially exacerbated by the degeneracy of multiracial Manhattan. Philip, however, has opted for a docile and static role in the plot. His response to the process of America’s uglification is self-absorption into his own nothingness. The will to power is sorely missing in all Perdue’s characters—including Philip himself.

Purdue is at his best when depicting his double—or for that matter, his own doppelganger Lee Pefley who personifies in all of his novels the dying White race. All of us, all the time, without any exception, and without ever wishing to publicly admit it, are in search of our double, and should we fail to spot it, we will promptly project it into an imaginary and often would-be glorious future of ours. Surely, Perdue’s double, Lee Pefley and his latest tragic avatar Philip, are follow-up figures on the early German romanticists whose techniques of transfiguration into the Other stretches from the dark romanticist E.T.A. Hoffmann to Edgar Allan Poe, all the way to some modern magic realists. There is, however, no need to speculate about the spirit of the readers in quest of their double, although one could take an educated guess that these are depression-prone individuals of exceptionally high IQ, with a zero will to fight. They usually spend their lifetime in wishful thinking about the advent of a glorious leader, yet are seldom able to make any worthwhile political decision. Poe’s short story Ligeia depicts a similarly dying, intelligent, albeit self-absorbed woman who finds her transfigured double in the equally death-stricken and self-absorbed woman Rowena. It is a great tragedy that many of those fine thinkers never had a chance to live parallel lives with their doubles within the same timeframe. Too bad for Philip that he had not met Ligeia in his earlier life and started working with her for the benefit of their common heritage. Philip’s passivity in the face coming disasters, which leads him to his suicide, cannot serve as a role model for modern White activists.

Tom Sunic’s latest book is the third edition of Homo americanus; Child of the Postmodern Age ( Arktos, 2018). The book includes a foreword by Kevin MacDonald and an afterword by Alain de Benoist.

Comments are closed.