On Yellow Vests and Monsters

“Any appeal to the white working class, as in today’s alt-right populism, betrays class struggle.”

Slavoj Žižek, The Philosophical Salon, 2019.

Commenting on the political aspects of Shelley’s life and poetry, Virginia Woolf asserted in 1927 that the poet’s England “has already receded, and his fight, valiant though it is, seems to be with monsters who are a little out of date, and therefore slightly ridiculous.” Woolf was referring to Shelley’s nineteenth-century opposition to a system in which journalists were imprisoned for being disrespectful to the Prince Regent, men were stood in stocks for publishing attacks upon the Scriptures, weavers were executed upon the suspicion of treason, and boys (Shelley included) were expelled from Oxford for avowing their atheism. Dramatic in its own time and context, by the decadent mid-1920s such activism had indeed become a little anachronistic on paper, even if I disagree with Woolf that it had become slightly ridiculous. The exertion of political power, after all, is a monster that may change costume and migrate in certain seasons, but is also a fixed reality of human relations and therefore no more ridiculous, in any guise or era, than the people it rests upon.

The profundity of Woolf’s comment, for me, therefore lies less in its discussion of Shelley’s poetry than in its exposure of Woolf’s own interwar sense of political security. It is this sense of political security that today seems the more out of date, and therefore slightly ridiculous, especially as we live in an age where the monsters of the past, present, and putative future, are perpetually invoked in all areas of life. Today, people are imprisoned for being disrespectful to certain races, men are stood in the postmodern equivalent of stocks for attacking certain ideologies, workers are today arrested more often for patriotism than treason, and children are threatened with expulsion for the new sin of ‘racism.’ Woolf’s smug security, and not Shelley’s poetic demonology of the political, thus seems quaint at a time when everything in the tumultuous present is discussed via reference to monsters that may at any moment return from their slumber or drop their mask, and are certainly not to be laughed at.

How does one fight today’s monsters, and who is fighting them? One of the most interesting aspects of the persistent Yellow Vest protests, about to enter their tenth weekend and once more growing in size, is that they have been claimed by almost everyone on the political spectrum. As such, no-one is yet clear as to what monsters the Yellow Vests fight, or which monsters the movement itself may give birth to. Although coming from an avowedly Marxist/Maoist perspective, Slavoj Žižek is almost certainly correct is his recent assertion that:

The yellow vests movement fits the specific French Left tradition of large public protests targeting the political, more than the business or financial, elites. However, in contrast to the 68’ protests, the yellow vests are much more a movement of France profonde (“deep France”), its revolt against big metropolitan areas, which means that its Leftist orientation is much more blurred. (Both le Pen and Melenchon support the protests.) As expected, commentators are asking which political force will appropriate the energy of the revolt, le Pen or a new Left, with purists demanding that it remain a “pure” protest movement at a distance from established politics. One should be clear here: in all the explosion of demands and expression of dissatisfaction, it is clear the protesters don’t really know what they want. They don’t have a vision of a society they want, just a mix of demands that are impossible to meet within the system, even though they address them at the system.

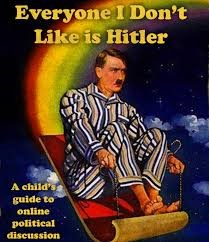

Attempts to define the protesters in simple terms appear doomed to failure. Not only have factions of French Yellow Vest protesters been filmed fighting each other in Paris, but in almost every attempt to export this protest model there have been similar splits and fights, as competing groups attempt to see themselves, and only themselves, in the Rorschach of riotous assembly. Most recently, in London, pro-Brexit Yellow Vest protesters and anti-Brexit Yellow Vest protesters clashed at Trafalgar Square, with reports of both sides calling each other ‘Nazis.’ Both the collapse into Yellow Vest vs Yellow Vest, and the mutual use of the ‘Nazi’ pejorative, are illustrative of the wider confusion of ideology and childish terror in the face of name-calling in postmodern politics. These phenomena also illustrate the fact that, as Žižek points out, none of these groups have a vision of a society they want (or will admit to wanting). One guide to characters in James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake is titled “Who’s Who When Everybody is Somebody Else?” — a question that could as easily be put to the labyrinthine and evasive nature of a postmodern political activism in which identities are claimed and simultaneously disavowed by all concerned.

The disavowals create their own rhetorical-ideological mazes. A staid and tired Old Right fights the Left’s almost recreational allegations of Fascism by asserting that it opposes the “real Fascists.” Meanwhile, at the first accusation of racism, “Nationalists” like Steve King frantically defend and enunciate their doctrine as meaning there is nothing special about their nation beyond a set of abstract values — values that are, in King’s words, “attainable by everyone … people of all races, religions, and creeds.”

That’s quite a nationalism. Our contemporary political context is thus one in which the Fascists are anti-Fascists, but anti-Fascists are Fascists who call the anti-Fascists Fascists, and while Nationalists like Steve King are apparently also multicultural Globalists, we are assured that the only thing we can sure about is that everyone is a Nazi. This isn’t a sentence from Joyce’s Wake, but it could be, because in today’s political zeitgeist Everybody is Somebody Else.

While the more ideologically senile elements of the Old Right are tragically entertaining and infuriating in equal measure, this isn’t to say the Left is free from its own conflicting and contradictory abstractions and evasions. Far from it. Žižek smugly observes of the Yellow Vests that their demands are a “combination of contradictory requests — ‘Please protect our environment while providing cheaper fuel!’” But isn’t the Left full of even more ridiculous contradictory requests? ‘Please let in droves of foreign workers while providing higher wages!’ ‘Please protect our environment while building masses of cheap houses for our growing foreign population!’; ‘Please keep us safe and free while importing terrorists and monitoring the internet activity of racists!’; ‘Please stop sexual harassment and objectification while encouraging the sexualization of all aspects of life!’; ‘Please fight racism while reminding everyone of the particular evil of the White man!’ The motto of the French Left’s protests in 1968 was ‘Soyons réalistes! Demandons l’ impossible!’ (‘Let’s be realistic! Demand the impossible!) It was uttered, at the time, entirely without irony, and yet how could the Left, which has internalized the motto with comical earnestness, escape irony now? The Left is now the embodiment of irony; a joke at its own expense, a bundle of contradictions wrapped in childish impetuousness and naivety.

Are the Yellow Vests, as Žižek implies, also a joke? Not in the most material of terms. Thus far, 12 people have died, about 1,700 protesters have been injured, and a thousand members of the security forces. Four people have had their hands permanently destroyed by explosive tear gas grenades, 60 have been shot in the face with rubber bullets, and 12 people have lost at least one eye. Fueling these sacrifices is a swelling rage, and there is a case to be made that the Yellow Vest movement is, even if it can’t itself see it, in large part and in its origins, ‘the Sound and the Fury’ of the abandoned White working class, with all the indecipherable raw emotion of the opening chapter of Faulkner’s magnificent novel of the same name. Setting aside the issue of violence, which is no rarity in multicultural France, the Whiteness of the Yellow Vests alone appears sufficient to send media traitors into hyperbolic spasms. (The [White] working-class and their difficult economic conditions are made clear in this documentary.) American feminist and journalist Lara Marlowe, Paris correspondent for the Irish Times, has asserted that “the revolt is ideologically closest to the far right. Gratuitous violence, racism, sexism, anti-Semitism and homophobia are the dark side of the movement that has plunged France into its worst crisis of the past half century.” She continues, with laughter-inducing earnestness:

The yellow vests’s hatred of high finance often translates into anti-Semitism. Just before Christmas, a group of yellow vests were filmed in Montmartre, making the quenelle, a version of a Hitler salute invented by the humourist Dieudonné. That night, a 74-year-old woman watched three men in yellow vests doing the quenelle in the metro. “That’s an anti-Semitic gesture. I am Jewish. My father died at Auschwitz. Please stop,” asked the woman. “Get lost, old lady,” shouted one of the men. “This is our country! This is our country!” chanted another, repeating the slogan of Le Pen rallies.

Rampant Yellow Vest sexism on display

Aside from anecdotes and overheard chants, however, one struggles to find something tangible in the Yellow Vests — a movement that appears proud of rejecting all political parties, yet suffering from the lack of focus such a relationship might offer. Is there anything in this movement that is useful or meaningful beyond its need to be seen and heard, and to achieve a couple of specific (and almost certainly temporary) changes in policy? Media commentary has become repetitive on this issue, revolving almost exclusively around the theme of visibility. “If the hike in the price of fuel triggered the yellow vest movement, it was not the root cause,” said the geographer Christophe Guilluy. “The anger runs deeper, the result of an economic and cultural relegation that began in the 80s. … Western elites have gradually forgotten a people they no longer see. … Whatever the outcome of this conflict, the gilets jaunes have won in terms of what really counts: the war of cultural representation. Working-class and lower middle-class people are visible again.” But is it enough simply to be seen? (See also this this interview of Guilloy, large portions of which were read by Tucker Carlson on his January 16, 2019 show (here, beginning at 31″). Carlson, like Guilluy, emphasized that this disconnect between elites and the [White] working class marks all Western societies.)

Amidst the sea of evasions, disavowals, and contradictions, it remains the case that the White working class has been abandoned by both the Old Right and the Left. In some cases, the White working class is the reason for the same evasions, disavowals, and contradictions: they are an uncomfortable, and now more visible, reminder of broken promises and unfulfilled obligations. Guilluy adds that “the economic divide between peripheral France and the metropolises illustrates the separation of an elite and its popular hinterland. Western elites have gradually forgotten a people they no longer see. The impact of the gilets jaunes, and their support in public opinion (eight out of 10 French people approve of their actions), has amazed politicians, trade unions and academics, as if they have discovered a new tribe in the Amazon.”

I disagree that visibility, presented in passive terms, is the key issue here. In fact, I believe a better analogy would be that of an Amazonian tribe that had been systematically targeted for extinction, and was assumed to have been incapable of mustering any kind of resurgence. We shouldn’t forget that it became common practice on the Left to pretend the White working class didn’t exist, and that it was also viewed as explicitly oppositional on the Left and among cosmopolitan elites to offer the White working class, as an ethno-economic group, any kind of material or ideological support. Žižek himself argues that “in a state of racial tension and exploitation, the only way to effectively struggle for the working class is to focus on fighting racism (this is why any appeal to the white working class, as in today’s alt-right populism, betrays class struggle).” In Žižek’s malicious dialectic, one betrays a real struggling class in order not to betray a hypothesized struggle of classes (which is actually a racial struggle). This dialectic is common language in Left-Liberal circles, and it’s the reason why quasi-Romantic talk of a “forgotten people” is much too kind to our enemies — enemies who betrayed, attacked, slandered, and debased rather than “forgot.”

The Marxist rationale for the abandonment of the White working class has been adopted across the Left, despite its most obvious flaw— a monoethnic state wouldn’t experience racial tension and would therefore theoretically be a better, or at least less distracted, arena for putative class struggle. In order to remain true to some amorphous future ‘class struggle’ then, working class Whites are being systematically deprived of employment, culturally marginalized, ethnically cleansed from their former strongholds, and submerged in racially agonistic social scenarios until, traumatized by chaos, loss, and violence, they might finally either collapse into the arms of the same Left that brutalized them, or, emaciated and emasculated, dissolve dismally into the multiethnic cauldron.

Slavoj Žižek: Class Warrior, Class Destroyer

How prominent is race and White identity in the actions of the Yellow Vests? The questions of class, race, demography, and culture are connected, and both subliminal (implicit) and primary, in the Yellow Vest phenomenon, but not in the crude manner suggested by Marlowe. Guilluy observes that the “globalised economy is efficient” but has failed “to create and nurture a coherent society.” He adds:

Employment and wealth have become more and more concentrated in the big cities. The deindustrialised regions, rural areas, small and medium-size towns are less and less dynamic. But it is in these places – in “peripheral France” (one could also talk of peripheral America or peripheral Britain) – that many working-class people live. Thus, for the first time, “workers” no longer live in areas where employment is created, giving rise to a social and cultural shock. … The globalised metropolises are the new citadels of the 21st century – rich and unequal, where even the former lower-middle class no longer has a place. Instead, large global cities work on a dual dynamic: gentrification and immigration. This is the paradox: the open society results in a world increasingly closed to the majority of working people.

It’s true that the return of ‘peripheral’ France to cosmopolitan, multicultural Paris created a shock among the elites. But wasn’t there another shock beyond the mere fact these people still existed? Wasn’t there a shock that the periphery would dare to make “old fashioned” economic demands of a type that had for some time been relegated to mere background noise in the clamor for the right to sodomy, feminism, cheap foreign labor, and ‘convenience’ abortion? In these areas there is perhaps no better commentator than E. Michael Jones, especially in this classic video. As Jones points out, in his own inimitable style:

Our friends on the Left, let me tell you, the fact that you now have homosexual marriage means that you cannot talk about economics any more … The Left sold out during the 1970s, where they said basically, “You give us sexual liberation and we won’t criticize your economic system.” And that’s why we have Goldman Sachs and Lloyd Blankfein endorsing gay marriage – because it’s in their interest, their economic interest. Homosexuals, and people who aren’t homosexuals but act like them, are easy to control. Once you have non-transient, fertile relations, the father feels that he needs a raise to raise his family, and suddenly he’s causing trouble with the personnel department … This is our definition of freedom: You can commit sodomy in the men’s room and that’s freedom. Of course, you’re not going to get paid a decent wage any more. It’s gone. The family wage is gone. So you better just get used to being a homosexual, and take what little wage we give you and be happy, and go to the disco and have sex with ten men … The revolutionaries in this instance were a cabal of three different groups of people: the CEO’s, the homosexuals, and the Jews.

In the clash between the Yellow Vests and the government elite in France, we saw not just a clash between a forgotten periphery and a cosmopolitan center, but a clash between struggling families and childless, city-dwelling elites who see themselves as world citizens and not as part of a living, breathing, reproducing France. The obvious nature of this clash had led the usual suspects to scramble for alternative interpretations, most comically in the form of Harvey Feigenbaum, a professor of political science at George Washington University, who told one media outlet that the weeks of intense rioting and rhetoric were due solely to the fact “people don’t like Macron.”

Harvey Feigenbaum: “Nothing to see here, goyim.”

Feingenbaum’s simplistic nonsense aside, news that a rival, cosmopolitan faction named the foulards rouges (‘red scarves’), are about to stage a massive counter-protest on January 27 is just further evidence of the creation of new warring ‘classes’ in which worldview as much as economics plays a significant formative role. The ‘red scarves’ have originated in Vaucluse, an area within the tourism hub of Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur — a more affluent area with lower-than-average agricultural employment and higher-than-average employment in high technology, biotechnology, and microelectronics. The Spectator anticipates “truck drivers and brickies wearing yellow vests” confronting “engineers and techies wearing red scarves.” The latter are overwhelmingly single, childless, media friendly, and enjoy a high disposable income. Their experience of multiculturalism is often limited to exotic restaurants or university-educated STEM workers from Asia. By contrast, the former, as Gavin Mortimer stresses, have had their lives lampooned and been smeared with a multitude of ‘isms’ and ‘phobias’ by politicians and journalists who, simultaneously, champion open borders because they believe Europe owes it to the third world. They don’t understand that the misery and poverty they think exists only in Africa and the Middle East is also found closer to home. The victims of globalisation are everywhere.

For me, it is this disparity that gets to the real heart of the problem with “visibility.” Because the issue here is with a kind of segregation, not between Whites and ethnics, but between Whites and those Whites who are not part of the deliberate, malicious elite, but who nevertheless exist within a relatively comfortable bubble in which, for the time being, they can afford to be ignorant of the looming racial storm on the horizon. This is an issue of fundamental differences in lived experiences. The best succinct summary of what I mean in this regard comes from Ron Unz’s “Open Letter to the Alt-Right.” Unz highlights the experience of multiculturalism among Silicon Valley types:

Silicon Valley is a different story. … There are huge numbers of other immigrants in the technology industry, and a noticeable slice of them are Muslims. Nearly all of these groups seem like perfectly fine people, very few are criminals, and virtually none are terrorists. Trump and Ann Coulter and others may talk about swarming hordes of “Mexican rapists,” but they just don’t seem to exist in real life. Rightwingers may claim that immigrant crime has been forcing affluent whites to barricade themselves inside gated communities, but Silicon Valley has no gated communities. For twenty years, Steve Jobs lived in an ordinary house sitting on an ordinary street, one which wouldn’t have seemed too out of place in the white-bread San Fernando Valley of the 1950s, and the same is true for many of the other top Silicon Valley execs. … So the problem is that when people notice that many of the things your organizations are saying are absolutely 100% contrary to what they actually see in their ordinary lives, they quickly conclude that you’re just as crazy as your critics in the MSM always say you are, and they immediately dismiss all of your other claims and ideas. Perhaps that’s not entirely fair, but it’s what happens. Meanwhile, certain other “alt-right”-type issues have very little daily resonance in Silicon Valley. For example, black behavior here is just as problematical as it is elsewhere, and blacks are responsible for a remarkably high fraction of all the serious local crime. But since there are very few blacks, it’s relatively easy for local “good-thinking” people to pretend not to notice the problem. Overall, California has by far the lowest black percentage of any large state, and for Silicon Valley, the figure is something like 3%, of which a relatively high fraction are middle-class engineers and such, while overall crime rates are too low for it to be much of an issue.

******

And with this, we find ourselves back, in a way, with Woolf and Shelley. But instead of being separated by decades and centuries, we find two groups co-existing at the same time, the one nonetheless finding the other’s monsters “a little out of date, and therefore slightly ridiculous.” Woolf laughed, and yet within a few short years the world she believed was secure would descend into chaos, damaged almost beyond repair. What monsters loom now, and who will dare to laugh at them?

Comments are closed.