Where is Calvin Coolidge When We Need Him?

In the 1952 American presidential election, Republican Dwight Eisenhower ran against Democrat Adlai Stevenson. Eisenhower was a five-star general in the army and Stevenson was the governor of Illinois. I’m so old I was in grade school back then and my teacher Miss Kelly, who was big for Stevenson—as I think about it, this may not have been altogether appropriate—put me up to standing on a corner in downtown St. Paul, Minnesota handing out Stevenson campaign literature to anybody who would take it.

My dad was a barber in the basement of the Saint Francis Hotel a block away, and I took a break from my political duties to pay him a visit. After saying hello to Dad in his satiny smock and watching a haircut, I gathered up my pile of Stevenson flyers and went up the stairs to the lobby of the hotel and the front door with the idea of getting back to work.

When I got to the top of the stairs, I saw a banner saying there was a meeting of the Minnesota Republican Party going on in the Saint Francis. There were a few cardboard posters propped up with sticks with pictures of what must have been party luminaries. About twenty men—all men in those years—stood talking to one another; I supposed they were party members between meetings. Making my way head-down through them on my way to the front door and the street, I stumbled and out spewed, it seemed like ten feet, all my Stevenson flyers with his picture on them. I was mortified and a bit scared—the barber’s kid, a collage of Stevenson faces on the lobby floor, and the Republicans in their suits looking eight feet tall to me who had stopped what they were doing to take in what had just happened. As it turned out, they couldn’t have been nicer. They all smiled and helped me gather up the flyers and wished me well and I went on my way. I’ve never forgotten that moment.

Maybe I’ve taken too long to get to what I want to say here, but the purpose of recounting this memory was to establish the context for the general observation that I think I’ve lived through a marked downturn in American politics: from Dwight David Eisenhower and Adlai E. Stevenson—grown-ups, serious men, men of real substance, both of them—to Donald Trump and Beto O’Rourke. Eisenhower and Stevenson had discrete comb overs, but neither of them had what looked like a lemon meringue dessert sitting on his head, and neither of them talked about the size of his member on the campaign trail. And Beto? Is he the one with REO Speedwagon on his mixtape? President Beto? Really? Eisenhower had been the Supreme Commander of the Allied forces in Europe during World War II and president of Columbia University. What exactly has Beto done that’s so great?

To get to the specific topic of this writing: a story, or I guess it’s a joke, my dad told me perhaps a few too many times when I was growing up. It had to do with a president from the 1920s, Calvin Coolidge. Coolidge wasn’t the most outgoing person in the world and he wasn’t known for his loquaciousness. The way the story/joke Dad told me went, a little boy, nine or so, went up to President Coolidge and said, “My dad bet me a nickel that you wouldn’t say three words to me.” After a pause, Coolidge looked at the tyke and said, “You lose.”

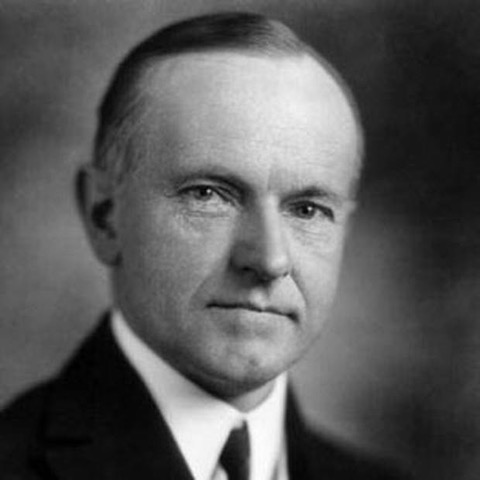

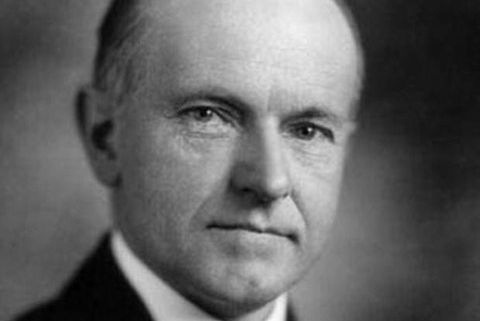

Calvin Coolidge. Born in 1872, died in 1933. Republican. Elected vice-president in 1920. Became president in 1923 upon the death of president Warren G. Harding. Elected president in 1924. Declined to run for a second full term as president in 1928.1

Calvin Coolidge

People who have done the talking all of my life don’t like presidents like Calvin Coolidge. They like top-down, activist presidents who make big things happen, big things that they, the talkers, personally favor—like wars, government control of people’s lives, and showy collectivist ideas: Abraham Lincoln (“Kill ‘em!”), Franklin Roosevelt (“Have I got a program for you”), John Kennedy (“We’re going to the moon!”), presidents like that. That wasn’t Coolidge. And more, the talkers don’t like people of Calvin Coolidge’s sort, period: tight-assed, conservative white guys. The argument here is that given my outlook—and since you’re reading this publication, probably yours—Calvin Coolidge was an exemplary American, and that we need Calvin Coolidge types front and center in this country’s public arena.

To understand Calvin Coolidge, you need to take into account where he’s from. He was born in Plymouth, Vermont and grew up among Vermonters, whom he referred to as “hardy and self-contained people.” I know what he was talking about; I have lived all of my adult life in Vermont.

Near the end of his life, Coolidge wrote:

Vermont is the state I love. I could not look upon the peaks of Ascutney, Killington, Mansfield, and Equinox without being moved. It was here I saw the first light of day; here that I received my bride. Here my dead lay buried, pillowed among the everlasting hills. I love Vermont because of her hills and valleys, her scenery and invigorating climate, but most of all I love her because of her indomitable people. They are a race of pioneers, who almost impoverished themselves for the love of others. If ever the spirit of liberty should vanish from the rest of the Union, it could be restored by the generous store held by the people of the brave little state of Vermont.

Indomitable people. Race of pioneers. Love of others. Spirit of liberty. And I’ll add that they are polite and respectful and decent and kind.

Coolidge was indeed indomitable. He never quit. “If I had permitted my failures,” he wrote, “or what seemed to me to at the time a lack of success, to discourage me, I cannot see any way in which I would have ever made progress.” Coolidge knew that he came from somewhere, that he was descended from a people with a history and a heritage they were proud of, and he gained strength and direction from that in the way he conducted his life. He was quiet about it, but he loved others: his wife and two sons, his neighbors, his community, his state and nation. And from all reports, he was a civil and giving person.

Very important as far as I am concerned, Calvin Coolidge was imbued with the spirit of liberty. He sought to free people, not control them. He didn’t hector people to be this way or that, and he didn’t take kindly to anybody else doing it. He bemoaned the fact that, in his words, “teacher desks are becoming soap box platforms.”

At its core, the American political system is an experiment in personal freedom and responsibility. It is the opportunity and the challenge to individual human beings to make something worthwhile out of their lives, in both the private and public spheres. It is the right of people to control their own destinies. American commitment to liberty is grounded in our Anglo-Saxon heritage: The Magna Carta, the Glorious Revolution.

Thomas Jefferson was enamored of the way of life in Saxony during the Middle Ages, where, as he saw it, small communities of people managed their own affairs free from dictates from on high. In a letter written late in his life, Jefferson wrote, “God send that our country may never have a government which it can feel.” If government is anything in our time, it is felt, and bent on being more felt, and still more, and more, and more, and more.

Of course, Jefferson is the primary author of the Declaration of Independence. His biographer, Joseph Ellis, wrote:

The explicit claim is that the individual is the sovereign unit in society; his natural state is freedom from and equality with all other individuals; this is the natural order of things. The implicit claim is that all restrictions on this natural order are immoral transgressions, violations of what God intended; individuals liberated from such restrictions will interact with their fellows in a harmonious scheme requiring no external discipline and producing maximum human happiness.2

Calvin Coolidge believed fervently in human freedom, along with its concomitant value, personal responsibility. To illustrate, I’ll venture a guess that Calvin Coolidge would approach the current opioid crisis with this message (I’m far more verbose here than he would be, but this is what he would get across): “If you are destroying your life with opioids and in the process hurting those close to you, I care deeply about what’s going on with you. But I’m going to level with you. All the government programs in the world aren’t going to save you from opioids. If it’s going to happen, you are going to save yourself from opioids. The way to get clear of your opioid self-abuse is for you to stop taking opioids. It comes down to that. It’s going to be difficult, at least at first—after that, you might be surprised at how easy it is to center your life around building yourself up rather than tearing yourself down. But however difficult it is, I believe you can do it. And when you do it you’ll be proud of yourself, and the people in your life will be proud of you. Even though I may get praised for all my understanding and compassion, I’m not going to give you reasons and excuses for failing to take charge of your life.”

Needless to say, that’s not how elected officials come at anything these days—but, as I see it, it would help if they did.3

How did Coolidge do as president? The American economy grew, wages rose, unemployment hovered around a low 3%, the national debt went down, tax rates fell, the budget was a surplus every year, and the federal government was smaller at the end of his six years than it was at the beginning. Not bad for a nobody-nothing president who’s been tossed down the memory hole of history by the enlightened among us.

Of particular interest to the readers of this publication, during Coolidge’s years, the Immigration Act of 1924, also called the Johnson-Reed Act, became law. It lasted until 1965, when it was replaced by the Immigration and Nationality Act, also known as the Hart-Celler Act, which undid its provisions. The 1924 law established immigration quotas based on the composition of the U.S. population in 1890 and had the effect of greatly reducing immigration from Eastern and Southern Europe, which especially affected the entry of Italians, Jews, Greeks, Poles, and Slavs. It virtually ended Asian immigration.

President Coolidge signs the Johnson-Reed Immigration Act of 1924

It’s clear where Coolidge’s sympathies lay in this matter. He was quoted as saying, “I am convinced that our present economic and social conditions warrant a limit on those to be admitted.” When he was vice president, Coolidge published an article in Good Housekeeping magazine entitled “Whose Country is This?” in which he wrote:

There are racial considerations too grave to be brushed aside for any sentimental reasons. Biological laws tell us that certain people will not mix or blend. The Nordics propagate themselves successfully. With other races, the outcome shows deterioration on both sides. Quality of mind and body suggest that observance of ethnic law is as great a necessity to a nation as immigration law.

In the main arena of public life in our time, who is saying anything remotely like that? Many would if they weren’t afraid. Calvin Coolidge had integrity, and he had courage (“brave little state of Vermont”), and I believe is he were alive today he’d find a way to get this idea across. There was a close fit between his most cherished beliefs and commitments, his expressions, and his actions.

Something close to my heart, The Kellogg-Briand Pact was formulated during Coolidge’s years. Frank B. Kellogg was Coolidge’s Secretary of State and Aristide Briand was the French Minister of Foreign Affairs. It was also known as The Pact of Paris. Its official title gets at its thrust, The General Treaty for Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy. I say close to my heart, because I’ve had it up to here with one government program in particular: mass destruction and killing.4

Briand had proposed a bilateral agreement between the United States and France to outlaw war between them. Coolidge and Kellogg suggested that the two nations take the lead in inviting all nations to join them in banning war. On August 27th, 1928, fifteen nations signed a pact in Paris promising not to use war to resolve disputes “of whatever nature or of whatever origin they may be, which may arise among them.” The signatories included, sadly enough, the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Japan. Later, an additional 47 nations signed on. The U.S. Senate ratified the agreement by a vote of 85–1, though making it clear that this country wasn’t giving up its right to self-defense or committing itself to acting against countries that broke the agreement.

President Coolidge (left) and Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg sign the Kellogg-Briand Pact.

Of course, a decade later signers of the pact embarked on the horror known as World War II. Fifty million deaths in Europe alone—take thirty seconds to contemplate that number. Cities devastated. The allies’ firebombing of Dresden. Recall the pictures of London early in the war and Berlin at the end of it. Atomic bombs dropped on civilian populations in Japan. Four hundred eighteen thousand American deaths, practically all of them young men just starting their lives, and none of them on American soil. It all had to happen, no way around it, no negotiated solution possible; seeing who could most effectively blow things up and kill people was the only way to resolve those issues. I don’t buy that line anymore.4

The point here is that Calvin Coolidge isn’t best known for saying “Speak softly and carry a big stick” and charging up San Juan Hill with the intent of ending the life of another human being. Kellogg-Briand failed, and perhaps those involved, including Coolidge, didn’t go about it in the most effective way. But I respect greatly the impulse behind it, and I’m trying to think of anyone center stage in our time even raising the possibility of taking things in this direction. It goes far beyond having fewer troops in Syria.

Those interested in the wellbeing and fate of white people would benefit from the presence in public life of men and women like Calvin Coolidge, as politicians and office holders and as white racial activists.

Someone like Coolidge would be an appealing candidate and incumbent in this country. The great majority of Americans are neither radical nor reactionary, far left or far right; they are middle-of-the-road folks. Coolidge looked like everyday people, he talked like them, he lived like them (not wanting to pay mortgage interest, he always rented modest houses), and he understood and respected them. He was soft-spoken and courteous. He served the citizenry, he didn’t come on as their boss, he didn’t talk about running the country. He married his wife (who grew up on Maple Street in Burlington, Vermont, a few blocks from where I sit writing these words) in 1905 and stayed with her until the day he died. He was a devoted parent. No scandals with Coolidge; he didn’t pay hush money to strippers. He didn’t broadcast his religiosity (Pence). He was racially conscious, but especially after he became president, he was low key about it. A highly intelligent and informed Amherst College graduate, his approach to the current immigration issue would involve more than shouting and tweets about building a wall. Electable, sympathetic to the cause of white people, sophisticated and nuanced, no personal baggage.

As a racial advocate, a modern-day Coolidge would bring a slant to things that deserves a place in white racial discourse:

Such a person would stay clear of labeling himself as a rightist, and the overall movement as an enterprise of the right. No alt-right, no dissident right. He’d present white advocacy as mainstream, centrist. Representative of the interests of two-thirds of the population of this country, white concerns aren’t inherently right-wing any more than black concerns, representing the interests of 13% of the population, or Jewish concerns, representing 2% of the population, are inherently left-wing. And in any case, to take on a right-wing identity is to get rejected out of hand by the vast majority of people and relegated to the fringe of American life and, drawing on an article I wrote for The Occidental Observer last year, figuratively or literally hit over the head with a club.

He’d be rooted in this constitutional republic, and he would think of himself as connecting with and continuing the American story. This, rather than, say, creating a white ethno-state. He’d stay clear of the white nationalism label, both to emphasize that his frame of reference is America and its European heritage and to avoid having to duck the club wielders.

He’d be grounded in Thomas Jefferson more than Julius Evola or Guillaume Faye (R.I.P.). He’d refer often and favorably to liberty. The words “individual” and “individualism” wouldn’t have negative connotations. He would assert that personal freedom and individualism are contributory, complementary—not contradictory, not dichotomous—to white racial consciousness and commitment. He would advocate the creation of small, intimate, supportive, white communities and networks.

He would exemplify and promote civility, tolerance, generosity, kindness, and self-sacrifice (he wouldn’t equate altruism with foolishness). He wouldn’t set white loyalties off against a love for all people. At the same time, he would recognize threats to our race and culture and country and the need to vigorously resist them.

He wouldn’t make race everything. Race would be vitally important, but so too would be honorable and productive work and honest self-expression, and place and love and family and friendship and service to others, and leisure and fun, and the fact that we are going to die.

Endnotes

- A good biography of Coolidge: Amity Shlaes, Coolidge (HarperCollins, 2013).

- Joseph Ellis, American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson (Knopf, 1997) p.9.

- A book that presents a rationale for approaching addiction in this fashion is Herbert Fingarette, Heavy Drinking: The Myth of Alcoholism as a Disease (University of California Press, 1988).

- For a riveting account of the reality of war, see Hampton Sides, On Desperate Ground: The Marines at the Reservoir, the Korean War’s Greatest Battle (Doubleday, 2018).

“The explicit claim is that the individual is the sovereign unit in society; his natural state is freedom from and equality with all other individuals; this is the natural order of things. The implicit claim is that all restrictions on this natural order are immoral transgressions, violations of what God intended; individuals liberated from such restrictions will interact with their fellows in a harmonious scheme requiring no external discipline and producing maximum human happiness.”:

For me – this encapsulates how Sweden also used to be. I find it truly heartbreaking that due to forced, unsolicited and unvoted for systematic changes to the immigration policies in Sweden, this is but a distant memory for some and a Sweden that young people will never know of.

Another great example of how this site leads you down blind alleys and dead ends to lead you away from discovering the truths of jooz.

Calvin Coolidge LOVED Zionists but the authors here would never tell you this because they want you on board with jooz not against them.

The convention of the New England Zionist Region here heard a message from President Coolidge confirming his sympathy with the Zionist movement. The following message was addressed by the President to the Hon. Elihu D. Stone, Assistant United States Attorney, who is chairman of the New England Zionist Region:

“I regret that the pressure of other duties will prevent me from attending the Convention of the Zionist Organization of New England at Worcester on June 1st, but I hope that you will extend to the delegates assembled my good wishes on this occasion. I have so many times reiterated my interest in this great movement that anything which I might say would be a repetition of former statements, but I am nevertheless glad to have this opportunity to express again my sympathy with that deep and intense longing which finds such fine expression in the Jewish National Homeland in Palestine.”

Thank you for bringing this to my attention.

Oh well, I will have to lower Silent Cal a notch in my esteem. But I still have enormous respect for him despite not being fully woke (or at least not willing to admit he is fully woke) on the JQ. He was a politician, after all.

Eisenhower was a five-star general.

Ike was many things.

Robert Welch’s book on Ike is a free download. It was a great underground hit.

https://archive.org/details/WelchRobertThePoliticianALookAtThePoliticalForcesThatPropelledDwightDavidEisenhowerIntoThePresi

thanks,

Jerry

Griffin’s description of Calvin Coolidge actually does remind me of someone active in the pro-white movement today.

Jared Taylor.

A very nice essay. Alas, we NEEDED Cal Coolidge at every point from 1965 (really, 1928, but I’m keeping with the racial theme) until perhaps 2008. But today, no, the situation is so far gone that we need a much, much hardier and indeed brutal soul. Coolidge tried, in his quietly heroic way, to save White America, and indeed, in the 20th century, who did more? The 1924 Immigration Act was possibly the greatest piece of legislation in US history. But ultimately, the politics he (and I) favored – liberty + keeping America White – failed. This was not Coolidge’s fault, but it is the reality today.

A White American Franco or Pinochet is all that can save us now.

Actually this problem is a biological war (races are biological sub-types), previously commented on the concept “Social Node.” The most powerful Social Node is the ethnic one.

It is defined that node is a space in which converge part of the connections (links) of other real or abstract spaces that share their same characteristics and that in turn are also nodes. These nodes in addition to being linked contain information that can be used and exchanged between them for a common goal.

The Jews as Ethnic Social Node are the most powerful, there are also LGTBI Social Nodes, Ethnic Minorities, Ideological, Religious, Generational, Cultural, etc.

But the Ethnic Social Node = Ethnic lineage = power.

Example: a solitary ant is weak and helpless, but millions of sisters together can shoot down a Leon or Elephant.

Finally the Jewish strategy is based on undermining the Ethnic Social Node of whites. They will use it in every society they infect. Tomorrow may be Asia and they will be filled with Africans.

Defensive and offensive strategy:

Educate white youth, literature, film, video, culture, music, independent pro-blanca.

Expose them in their lies and interests (the Jews, they will try to censor)

Create autonomous homogenous white communities

Colonize virgin environments (expelling non-whites from the USA, France, UK, Germany … would be almost impossible), ahem: Alaska which is the least populated state, Antarctica which is a depopulated continent, Submarine environments, three quarters is ocean, Japan already plans to create cities in the ocean bed.

The latter must be done without interference from the governments since they are anti-white Zionist globalists.

The white man came to the moon, so he could conquer other environments.