Dragged Across Concrete (2019) and the Art of Cinematic Trolling

The author writes at Logical Meme and @Logicalmeme.

9125 words

Since the 1960s, there have been sporadic reactions in film against emergent liberal hegemonies in culture. In the early 1970s, when the social changes borne of the countercultural 1960s were, in very short order, becoming the mainstream culture and translating into the disastrous social policies of that era, there were occasional sympathetic depictions from Hollywood which channeled White discontent and a growing White male anxiety — for example, Dirty Harry (1971), The French Connection (1971), Death Wish (1974), and Taxi Driver (1976) — but by the 1990s, articulation of this anxiety (which, as a sociological phenomenon became hardened, not softened, through decades of collective experience) was largely expressed, ironically, through unsympathetically depicted characters — for example, Falling Down (1993) and American History X (1998)[1].

Since this time, the Hollywood filmmaking pipeline has become thematically constricted by a radical surge of political correctness and leftwing, agenda-driven depictions of race and racial conflict. Unspoken rules ensure that any film dealing with race ultimately settles on the side of predictable, leftwing, social justice platitudes. (Various Oscar-winning films of recent years attest to this.) As such, when it comes to subjects such as racial conflict, the effects of mass immigration, or the plight of Whites in America, there is simply no diversity of opinion coming out of Tinseltown. Creatively, this has led to a metastasizing sameness, a bland and boring creative funk, to mainstream films that touch upon such subjects.

In terms of the sociology of filmmaking, the significance of Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (2004) was to demonstrate — in stark, jaw-dropping, financial terms — the profound imbalance between the demand for ‘conservative’ films and the sparse supply of such films coming out of a leftwing, Jewish-dominated Hollywood system. Passion was independently produced and distributed by Gibson’s Icon Productions, going on to earn over $600 million worldwide, and currently stands as the highest-grossing R-rated movie in history. (The film also confronted strong rebuke and charges of anti-Semitism from prominent Jewish individuals and organizations.) Gibson’s next film Apocalypto (2006), also produced by Icon Productions, depicted violent, genocidal, tribal conflict in sixteenth century Mexico, and alluded to the eclipse and decline of Mayan civilization, emphasized in the film’s penultimate scene of Spanish Christian conquistadors arriving by ship to the jungle’s coast, with the indigenous locals looking on in awe. (Not surprisingly, Apocalypto was castigated in some quarters for harboring racist and colonialist apologetics.)

In the same way that Icon Productions has helped fill the vacuum of unmet demand for more conservative, religious, and un-PC films, Cinestate, a B-movie production company located in Dallas, Texas, and “backed by an anonymous Texas oil heiress” (Schwartzel), is producing films that deviate from the stultifying liberal guard rails. Cinestate’s business strategy revolves around a target audience of cinematically-disenfranchised Red Staters. “If we can make a movie that does not treat them as losers, or ask how dare they vote a certain way, or pander to them,” notes Cinestate founder and CEO producer (and Texas-native) Joseph “Dallas” Sonnier, “naturally they’re going to respond in a positive way.” “It’s funny,” he adds, “that, in this moment in time, the movies we’re making are almost counterculture” (ibid)[2]. That being said, Sonnier doesn’t see Cinestate’s films as being made for “Trump supporters,” as liberal media profiles are wont to do. “I didn’t even vote for the guy,” he says. “I don’t necessarily crave a conservative audience, but that may be an outcome, and it wouldn’t surprise me. I understand that audience deeply. But it’s not a mission statement” (Miller).

For instance, The Standoff at Sparrow Creek (2018), produced by Cinestate, is an impressive debut by writer/director Henry Dunham. Made for only $500,000, and with a respective 73% Rotten Tomatoes score, the film is a compelling whodunit think-piece that, in its dialogue-driven stagecraft, harkens to Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs (1992). Plot-wise, Sparrow pivots around White militias and police investigations into them, and features an all-White cast (virtually unheard of today) comprised of established character actors.

Cinestate has also released the three films made by writer/director S. Craig Zahler to date: Bone Tomahawk (2015), Brawl in Cell Block 99 (2017), and Dragged Across Concrete (2019). Even within mainstream film criticism, Zahler is being heralded for elevating the mechanics of B-movie pulp into serious film. From one perspective, Zahler traffics in grindhouse exploitation tropes; from another, he is a post-Tarantino, closeted conservative auteur.

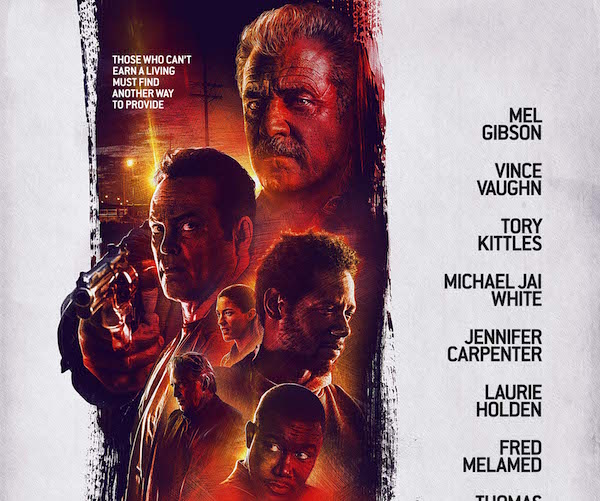

Even when working from within these independent film production outlets, filmmakers with non-liberal perspectives are increasingly forced to allegorically encode their views in ever more creative ways, akin to how White identitarians and White nationalists are increasingly forced to encode their language (through memes, irony, and surrogate words and phrases) on social media platforms. This is especially true for filmmakers expressing iconoclastic political views on race or the effects of mass immigration, such as Ruben Östlund’s recent film The Square (2017). Zahler is clearly in this camp, and from this perspective, his films can be interpreted as episodes of cinematic trolling. From his deliberate casting of known conservatives Mel Gibson, Vince Vaughn, and Don Johnson, Zahler seems to delight in provoking liberal intolerance, pushing their buttons to elicit a response. (This will be discussed in more detail below.) In the scope of this essay, I will focus on some of Dragged’s more salient references to race, as well as to feminism and the consequences of our feminized culture in general.

As I previously addressed in more detail in my review of Brawl, it is also my contention that Jung’s model of art as a manifestation of the creative unconsciousness helps explain both the creation and appeal of various metaphors, allegories, character journeys, and narrative structures that emanate from an artist. To a historically unrivaled degree, Cultural Marxism has succeeded in stifling healthy psychological individuation among Whites, primarily by making taboo any and all outward expression of racial consciousness. In such a repressive climate, works of art that touch upon White racial consciousness (however indirectly or subconsciously) will resonate. One can argue that the collective unconscious of an increasingly dispossessed White America is the ‘demand’, with the ‘supply’ being those works of art and culture which satisfy the psyche. Whether through movies, music, memes, or literature, Jung’s unconscious Shadow archetype expresses itself as the antithesis of whichever collective personality type is the dominant, actualized, conscious zeitgeist of the day. In reaction to this suppressed and bottled-up aspect of White racial consciousness, the Shadow surfaces vis-à-vis sublimated, metaphorical surrogates.

***

Zahler’s influences run the gamut. He’s clearly indebted to classic, violent antihero films of the 1970s (e.g., Don Siegel; Sam Peckinpah; early Martin Scorsese), B-movie grindhouse, as well as neo-iterations of both genres (predominately through the work of Quentin Tarantino). Stylistically, one can discern the influences of Kubrick (in static shots with symmetrical mise-en-scène), Antonioni, and Tarantino. Zahler has professed a longstanding obsession with Akira Kurosawa, but has also had an interest in splatter films (e.g., Sam Raimi, George Romero, Tobe Hooper) since he was a teenager (see Tobias). A prolific writer who has written numerous scripts and novels, Zahler grew up reading pulp horror and dark fantasy (e.g., H.P. Lovecraft, Robert E. Howard, Edgar Rice Burroughs) as well as classic hard-boiled detective fiction (e.g., Jim Thompson). He is also an accomplished musician who co-writes his own film scores, which are in different genres from soul to jazz, as well as songs for his heavy metal band side project.

With respect to his writing process, Zahler emphasizes that character drives his storylines, not the other way around. “I am not looking for films to express values,” he says. “That’s getting dangerously closer to an ‘agenda movie,’ which is a movie in support of its thesis statement. My characters drive my movies.” (See Tobias). In another interview (Schager), he says: “My writing process is to surprise myself daily. There are always surprises, and a lot of those surprises are a humorous moment, or a revelation about someone’s backstory, or a connection between two characters. That sort of stuff.”

Zahler’s first film, Bone Tomahawk, is set in the American West of the 1890s and revolves around White hero protagonists battling a savage tribe of cannibalistic American Indians, a setting and conflict that immediately makes the hair on a liberal’s neck stand up. When Brawl came out, a film with a contemporary setting, liberal critics were a bit taken aback by the brazen use of racial antagonisms, as well as the ‘racist’ language of its protagonist, but such critics missed many of Zahler’s deeper race-centric themes. The same is true for Dragged Across Concrete.

Plot & Symbolism

SPOILERS AHEAD. The opening scene of the film, as well as the closing scene of the film, feature Henry (aka “Slim”) Johns (Tory Kittles), a late 20s Black male. While Gibson and Vaughn are the A-list actors that Dragged understandably focuses upon, Henry is something of a third protagonist. By film’s end, the paths of all three characters will have crossed, and not necessarily for the better. The opening scene of the film also serves as a troll on diversity: We see Henry, fresh out of prison, having sex with an Asian-American hooker, a girl he knew from school. Henry then returns to his mother’s ghetto apartment building and finds her prostituting herself to a skittish White man. (His mother’s prostitution is notably depicted less from desperation as from a type of laziness, a characterization that will be revisited in the film’s denouement, as this same woman, now wealthy behind her wildest dreams, is not bettering herself per se, but is receiving a massage from a young White male.) Henry chases the scared john out with a baseball bat and, referencing the trash bags in the hallway, commands him to “Take those garbage bags that are outside down to the trash.” The scared White john, out of his element, complies, symbolizing White fear of, and genuflection before, Black aggression and displays of dominance.

“What happened to your job at the grocery?” Henry asks his mother. “I got fired,” she replies. The reason for her firing is left to the audience’s imagination. An exchange of dialogue between Henry and his mother captures the pathologies of the Black underclass, as well as some politically incorrect flourishing which reflects Black underclass attitudes:

Henry: I left you money before I went in, plenty for twice as long.

Mother: It ran out.

Henry: Yeah… And I can see its footprints up and down your arms.

Mother: Look, you ain’t got no right lecturing me about nothing.

Henry: You can’t be doing this. … Hooking, needles… and especially not in front of Ethan at all ever.

Mother: He ain’t a toddler no more.

Henry: And you doing those things around him. … It’ll mess him up permanent.

Mother: So, you gonna take care of us now, huh? Like your cock-sucking father did when he ran off with his faggot-ass boyfriend?

Henry: Pops is a yesterday who ain’t worth words.

Henry promises to help her out financially, but in the meantime, he tells her, “Start organizing yourself and this place.”

Shotgun Safari

Henry then knocks on the bedroom door of his wheelchair-bound younger brother, Ethan (Myles Truitt). (It is implied that Henry went to prison for exacting revenge upon whomever put his younger brother in a wheelchair.) Due to his circumstances, Ethan is addicted to video games and dreams of being a video game creator. The brothers proceed to play a fictitious video game called “Shotgun Safari”, which involves killing lions and other creatures in the wild. A symbol-rich ‘lions’ allegory will occur several times throughout the film, capturing how our society may be regressing back to the law of jungle:

Ethan: Okay. You gotta be careful around these parts. It’s got lions.

Henry: Can we shoot them?

Ethan: Well, yeah, but it’s gonna be pretty hard, unless you have a pump-action shotgun.

Henry: Alright, we get one.

[Ethan shoots lion.]

Henry: Nigga iced that feline!

Ethan: Okay, look, we gotta go. There’s more coming. Okay, once you get across this stream, we gotta look out for boa constrictors.

Henry: This nigga’s ready for a real safari!

Ethan: Even if my legs worked right, I wouldn’t wanna be hunting animals for real. It’s like some rich White people shit.

Henry: Still, you real good at this game.

Additional clues can be found in the soundtrack’s songs “Shotgun Safari” and “Street Corner Felines,” both of which Zahler wrote the lyrics for. “Shotgun Safari” equates the streets of the city as a jungle (“Life after prison ain’t easy / This neighborhood’s no longer safe… Can’t trust the police… Stray dogs roam these streets.”) As is noted further below, with respect to one of the White cop protagonist’s family context, the lion analogy is also made apparent. It is worth noting that the very last image of the film is of a fantastically-enriched Henry and Ethan, living in an expansive mansion, playing “Shotgun Safari” again, with the film’s last line being: “Let’s hunt some lions.”

***

Lurasetti & Ridgeman

The central plotline of Dragged follows world-weary cops Brett Ridgeman (Mel Gibson) and Anthony Lurasetti (Vince Vaughn) of the Bulwark Police Department. The fictional city name, which conventionally refers to a defensive wall, is likely intended as a metaphor for the encroaching entropy and chaos that creeps forward when walls fall down, or when they fail to be erected altogether, and when police (acting as a bulwark against chaos and incivility) become disengaged due to political correctness.

After staking out a Hispanic drug dealer (Vasquez), Ridgeman and Lurasetti trick Vasquez into attempting to escape out the window onto the fire escape. There, Ridgeman pins Vasquez down, and with his boot on Vasquez’s head, presses him for information, inflicting pain in the process. Unbeknownst to the two cops, another tenant in the building is filming their every move, a nod to the ubiquitous cell phone subculture of urban dwellers filming any and all police encounters. With Vasquez subdued and hand-cuffed to the fire escape, Ridgeman and Lurasetti then enter the apartment and proceed to question Vasquez’s girlfriend, Rosalinda. “Her handbag seemed a little heavy,” says Ridgeman to Lurasetti as the latter inspects it. “You been taking into account the amount of make-up Latinas carry?” quips Lurasetti, before finding a gun in her purse. In a twist on the longstanding tactic of Hispanic criminals pretending to “no hablar Ingles” when being questioned, the two feign not being able to understand Rosalinda’s hearing-impaired and broken (but coherent) English. “I didn’t understand that, did you?” Ridgeman asks Lurasetti. “No,” replies Lurasetti. “Sounded kind of like ‘dolphin’.” We see Ridgeman and Lurasetti cruelly renege on their promise that, if Rosalinda tells them where Vasquez hid a duffle bag of drugs and money, they’ll forget about finding the gun in her purse. She tells them where the duffle bag is hidden. Ridgeman then calls for backup and for the arrest of both Vasquez and Rosalinda. “You said if I told you where the bag was, you’ll let me go,” she asks them. “Can you understand her?” Ridgeman rhetorically asks Lurasetti. “No,” Lurasetti replies.

Post-incident, Ridgeman and Lurasetti retreat to their favorite diner for breakfast. Over the diner’s sound system, a song plays, featuring an androgynous-sounding singer. It’s banal pop with politically correct lyrics: “We can be considerate / To people or strangers / Until you get to know them / Ooh.” Ridgeman asks Lurasetti: “This a guy or a girl singing this song?” Lurasetti listens for a bit. “Can’t tell,” he replies. “Not that there’s much of a difference these days,” says Ridgeman. Lurasetti adds, “I think that line was obliterated the day men started saying ‘we’re pregnant’ when their wives were.”

Their breakfast is interrupted by a call summoning them to the office of their boss, Lt. Calvert (Don Johnson). Calvert informs them that the 6 o’clock news will be airing the cell phone video of their heavy-handed interaction with Vasquez[3]:

Calvert: Our inspector… our Mexican-American inspector… is unlikely to be lenient.

Ridgeman: Politics, like always.

Calvert: Like cellphones, and just as annoying, politics are everywhere. Being branded a racist in today’s public forum is like being accused of communism in the ’50s. Whether it’s a possibly offensive remark made in a private phone call or the indelicate treatment of a minority who sells drugs to children, the entertainment industry, formerly known as the news, needs villains.

Lurasetti: There’s certainly nothing hypocritical about the media handling every perceived intolerance with complete and utter intolerance.

Calvert: It’s bullshit. But it’s reality.

Lurasetti: But I’m not a racist. Every Martin Luther King Day, I order a cup of dark roast.”

Ridgeman, Lurasetti, & Lt. Calvert

Both men, who are financially strapped, are put on a 6-week suspension without pay, an event that propels the rest of the film’s events.[4] Calvert dismisses Lurasetti from the room but asks Ridgeman to stay behind. In the ensuing conversation between these two men with English surnames, the mise-en-scène of the shot highlights the difference between the two. Calvert has played the political game to advance his career, while Ridgeman has stayed true to his old-school, street-cop methods. On Calvert’s side of the desk, we see awards and framed newspaper accolades; on Ridgeman’s side of the desk is only glass and the skyline of Bulwark, a metaphor for how Ridgeman represents the ‘bulwark’ of old, a bulwark against the city being overrun by criminals, against the police being cow-towed by the cell-phone-wielding, ‘snitches get stitches’ constituency.

Calvert: Ridgeman, gotta be aware of this stuff. Digital eyes are everywhere.

Ridgeman: I do what I think best when I’m out there. I was that way when we were partners, and I’m still that way now.

Calvert: There’s a reason I’m sitting behind this desk running things, and you’re out there crouching on fire escapes in the cold for hours, with a partner that’s 20 years younger than you.

Ridgeman: Hey, Anthony’s got a mouth with its own engine, but he’s solid.

Calvert: That wasn’t my point. … I watched that video a couple times. You threw a lot more cast-iron than you needed to. And when we worked together, you weren’t that rough.

Ridgeman: And?

Calvert: It’s not healthy for you, to scuff concrete as long as you have. You get results, but you’re losing perspective and compassion. Couple more years out there and you’re gonna be a human steamroller covered with spikes … and fueled by bile.

Ridgeman: There’s a lot of imbeciles out there.

Calvert: Yeah.

Post-suspension, we see Lurasetti enter Feinbaum’s jewelry store, to pick up the engagement ring he ordered and plans to spring on his mulatto girlfriend, Denise. Zahler, who is himself an atheist Jew (see Schager), canvases the scene with various stereotypical tropes of the Jewish jeweler and credit financier, as well as Jewish occupational choices[5]:

Feinbaum the Jeweler

Lurasetti: I got an issue at work.

Feinbaum: Do you need a payment plan? I’d be more than happy to…

Lurasetti: Thanks. I saved enough for this. It’s a different kind of problem.

Feinbaum: My wife has two brothers who are therapists, and three sisters who were lawyers.

Lurasetti: Well, my problems don’t require those kinds of professionals. I just… I’m thinking about the kind of future I can offer my girlfriend and, you know, that life won’t have a lot of diamonds.

The film eventually cuts to Ridgeman’s teenaged daughter, Sara, walking home alone from school, which is in a non-desirable part of the city where the Ridgemans live. (We’re led to believe that the neighborhood, which the Ridgemans have lived in for many years, has gone downhill.) A group of four Black teenagers hanging out on the street (which naturally implies they are school drop-outs) proceeds to hassle her, one of them on a bike, and carrying a fast food soda cup, peddles up behind her and throws orange soda all over her. The others start laughing. When Sara gets to the family’s building apartment, we see her lock the door’s several bolts while muttering to herself: “I won’t. I won’t.” — a sentiment that may relate to her promise to herself not to “become a racist.” (The locking of doors, and the importance of doing so, is a recurring motif throughout the film. Our multicultural era is one of locked doors and depleted social capital.) Sara’s mother Melanie (Laurie Holden), who is Brett’s wife, walks into the room with a cane (we learn later that she has MS and used to be a cop herself) and comforts her daughter. That evening, Melanie tells Brett about the orange soda incident:

Brett: What kids?

Melanie: The ones she didn’t recognize. Four Blacks, one on a bike. But does it actually matter who? This is the fifth time. This fucking neighborhood. It just keeps getting worse and worse.

Brett: Is she okay?

Melanie: Well, yeah, but coming home from school and walking four blocks shouldn’t be an ordeal.

Brett: No. It shouldn’t. Did you offer to pick her up at the bus, escort her back?

Melanie: Of course I did. She knows it isn’t easy for me to get around a lot. And she’d be too embarrassed anyways.

Brett: Well, she’s got two sets of cop DNA, so of course she’s tough.

Melanie: Yeah, especially for her age and gender. But she’s getting older, more womanly. And these boys are gonna start having different kinds of ideas about her pretty soon, if they don’t already. … You know, I never thought I was a racist before living in this area. I’m about as liberal as any ex-cop could ever be. But now… We really need to move.

Brett: I know.

Melanie: No. Yesterday or the day before.

Brett: I know.[6]

Ridgeman knocks on his daughter’s bedroom door and invites her to watch “that show about the lion cubs.” We then see them both sitting on the couch, watching a documentary which shows a lion cub with its mother. “They’re so cute before they get big,” says Sara. As mentioned earlier, at several different points in the film, a lion allegory is used to represent both the violent lengths a White father will go to support his wife and daughter (Ridgeman), the similar lengths a young Black man will go to provide for his brother and mother (Henry), as well as the lengths a criminal, in the generic sense, will go (in killing a lion, lioness, or cub) for sport or to help their own non-lion kind (e.g., the psychopathic bank robbers wantonly murdering innocents.) There may be a deeper sociological relevance for the “Shotgun Safari” video game that Henry and his younger brother play; while Henry’s motivations in this film are noble, Zahler may be trolling here, given the sociological reality of Black males committing the vast majority of society’s violent crime. In other words, the likelihood of Henry representing the typical Black ex-con is likely quite remote.

With his mind made up to rob a presumed drug dealer, we see Ridgeman enter a shopping mall, en route to visit criminal-world-liaison Friedrich (Udo Kier), whose front is a high-end men’s clothing store. Upon entering the Mall, Ridgeman sees scantily clad, un-chaperoned, teenaged girls coming down the escalator. With a disgusted, yet worried, expression on his face, Ridgeman conveys an entire dialogue with just a heavy sigh, realizing that this picture may be what’s in store for his daughter. In Friedrich’s dimly lit, well apportioned office (the lighting reminiscent of The Godfather; the stuffed bird harkening to Psycho), Ridgeman makes his Faustian bargain.

On the first night of their illicit stakeout of Lorentz Vogelmann (Thomas Kretschmann), whom Ridgeman believes is just a drug dealer, Ridgeman waits for Lurasetti on a street corner at night. While waiting, Ridgeman sees two hoods climbing a fence, obviously intending to rob a business, but Ridgeman does not act and no longer cares. A hint of nihilism creeps in and is accentuated with Ridgeman’s quasi-market-economics version of morality; he tells Lurasetti that anything they do from that point on is strictly for the payoff, not loyalty or friendship. When Lurasetti, already in too deep with Ridgeman’s plot, realizes the full extent of Ridgeman’s ambitions, he demands answers from Ridgeman on why he is doing this:

Ridgeman: I’m a month away from my 60th. I’m still the same rank I was at 27. For a lot of years, I believed that the quality of my work, what we do together, what I did with my previous partners, would get me what I deserved. But I don’t politic and I don’t change with the times. And it turns out that that shit’s more important than good honest work. So yesterday, after we stop a massive amount of drugs from getting into the school system, we get suspended because it wasn’t done politely. When I go home and I find my daughter has been assaulted for the fifth time in two years, because of the shit neighborhood my shit wage has forced me to live in. And my wife can’t help. She’s barely getting through the day on her meds as it is.

Lurasetti: They okay?

Ridgeman: Yeah. Melanie’s coping. Sara’s doing okay. She’s dealing with it better than most kids her age would. But who knows what kind of long-term damage is going on with her. There have been opportunities before, more than a few. Take a bribe, pocket a bundle, pilfer cash. I was a cop on active duty. Today, I’m a poor civilian who’s nearly 60. I can accept that, but I’m not gonna ask my wife and daughter to.

Ridgeman further justifies his intentions by telling Lurasetti: “We have the skills and the right to acquire proper compensation.”

***

Things spiral out of control when Ridgeman and Lurasetti realize that Vogelmann (who sports a German accent) and his band of psychopathic accomplices (whose look and behavior resemble Nazi caricatures) are not drug dealers but bank robbers.[7] The patient stakeout and tailing ops by Ridgeman and Lurasetti lead them to witness a savage bank robbery, but their inaction in calling the police situates them into a moral zone of complicity, due to the carnage that ensues in the bank.

The Vogelmann gang has employed Henry and his friend Biscuit (Michael Jai White) as getaway drivers. Interestingly, Henry and Biscuit wear a layer of whiteface makeup as they wait in the van outside the bank. When the entire gang leaves the bank in the getaway van, having stolen gold bars worth millions, Henry and Biscuit remove their whiteface makeup.

Henry removing his whiteface paint.

Despite their ‘acting’ White vis-à-vis makeup, Henry and Biscuit’s linguistic ebonics is taunted both by the psychopathic Vogelmann crew and, later, by Ridgeman. When the van is approaching the post-robbery destination, Henry says “We here,” to which one of Vogelmann’s psychos asks rhetorically: “We are here or we’re here?” Later in the film, when Henry uses the phrase “who don’t know nothing”, Ridgeman corrects him:

Ridgeman: I believe what you meant to say was, ‘Who don’t know anything.’

Henry: You understood me, didn’t you?

Ridgeman: Yeah, but you’re a lot smarter than you sound, a whole lot smarter from what I’ve seen.

Henry: It’s good to be underestimated.

In the movie’s final bloody shoot-out sequence, things unravel for most of the parties involved. In a particularly gruesome scene, the Vogelmann crew are forced to perform an abdominal incision on a corpse, to search the stomach for a set of keys the individual had swallowed. The two nameless Vogelmann gang psychopaths discuss the procedure:

Psychopath A: It’s the pale sac in there, the one that looks like…

Psychopath B: I know which one it is.

Psychopath A: Careful not to pop his liver. That is the worst smell in the world, Black guys especially.

I point out this exchange for a few reasons. First, it implies the two have military backgrounds, in particular, special ops backgrounds (given that this is not the first time one of them has done such a procedure, and multiple times on a Black corpse, to boot). Second, it feeds into the Nazi caricature angle. Lastly, it alludes to the men’s lived-experience of cultural race differences (the diets of Blacks) translated into biological differences (the smell of the punctured liver), which may be Zahler giving a trolling nod to race realism.[8]

In the last act of the film, and in league with the Kelly Summer interlude, the ‘crawling hostage woman’ scene is symbolic of White women being told that a certain course of action (which, in the film, involves the killing of a White man, at the instruction of the psychopathic villains) is in their best interest, when it is in fact a suicidal act.[9]

After the melee of bullets and blood, only Ridgeman and Henry remain, and a Prisoner’s Dilemma is fully embodied:

Ridgeman: We should clean up this mess together and split the gold. We can fight each other some more, do this until we’re crippled or dead, or we can both be rich. I don’t see how this is a dilemma.

Henry: Trusting a cop, one that’s crooked as fuck, is the dilemma. Only thing absolutely certain about you is that you don’t give a shit about any oath you swear to.

A last observation is that Ridgeman’s fateful decision towards Henry is likely motivated by a rational heuristics regarding typical Black male criminal behavior. It’s unlikely, but possible, that Ridgeman would have reneged on giving Henry his cut, but Ridgeman was more preoccupied with obtaining (and destroying) Henry’s cell phone ‘insurance policy’, which was incriminating video Henry took of Ridgeman and Lurasetti from a distance, when things went to Hell in a handbasket during the Vogelmann shoot-out.

Liberal Critiques: Ambiguity as Trolling

One of the best measures of the efficacy of a filmmaker’s coded sentiments (whether conscious or unconscious) is to analyze liberal critiques of the respective films. With Dragged, such critics were already primed to be on the lookout. They already know that both Mel Gibson (whom they thoroughly despise as a person, but begrudgingly acknowledge is a terrific actor and director) and Vince Vaughn — the leads in Dragged — are conservatives (as is Don Johnson), and so suspect that Zahler himself must be as well. Many of these critics accuse Zahler of trolling; in fact, if there is an emergent theme to liberal criticism of the film, it seems to be that Dragged is racist and misogynist, and that it constitutes trolling.

There has been no shortage of film critics willing to throw the R-word (and worse) at Zahler. In The Daily Beast, the title alone of Marlow Stern’s review of Dragged conveys the sort of sententious moral preening that is all too common: “Mel Gibson’s New Police Brutality Movie Is a Vile, Racist Right-Wing Fantasy.” In Vulture, David Edelstein calls Dragged “your basic boneheaded, right-wing action movie — skewed so that its heroes’ moral relativism is meant to be a sign of their manly integrity. A man’s gotta do what a man’s gotta do — however shortsighted and racist and sadistic.” We can speculate that coastal elites like David Edelstein have little idea what is involved in real, day-to-day policing. To him and his ilk, proper policing is defined solely through criteria of abstraction, sophisticated theorizing, perfect information, and always-sufficient time to reflect and rationally decide upon the right, proper, and just course of action. There is no room for heuristics, hunches, and split decisions, no place for the sort of Burkean ground-up knowledge that years of experience on the street brings to the table. “Collaring a Spanish drug dealer might involve stepping on his cabeza,” Edelstein writes, “but given that the scumbag deals to kids on playgrounds, that’s no biggie, right? If you think it is a biggie, this won’t be your sort of movie.”

In our contemporary, intolerant, gotcha culture, where careers and lives can be ruined simply for expressing a single politically incorrect sentiment, a real source of frustration among Zahler’s liberal critics is his political inscrutability. Many such critics have excoriated him for maintaining a level of ambiguity on such matters, especially in regards to the race-related views of his films’ White characters, which drives these critics crazy. As noted earlier, deliberate ambiguity of authorial intent in filmmaking, especially if such intent is of the Dissident Right variety, is very much akin to the need to encode beliefs, or use irony, on social media platforms. This is not to say that Zahler is, in fact, sympathetic to the Dissident Right. But a writer-director who was sympathetic to the Dissident Right, or even to the more tempered, close-to-the-mainstream, conservative positions, would be wise to deploy such obfuscatory tactics.

During the press barrage for the film’s release, Zahler, in interviews, has been peppered with questions about his political orientation. In a Daily Beast interview with Nick Schager, for instance, Zahler consistently dodges a line of questioning that seems desperately intent on uncovering the director’s politics:

Some critics consider your films conservative-oriented, and Dragged Across Concrete has only reinforced that view. Do you agree with those assessments about your work’s politics?

The last part of the artistic process is letting go of your work and giving it to people who have their own private experiences with it. I’m not politically driven; I’m not very politically interested. None of the stuff I write comes from the point of view that I want to push an agenda, or have a piece that is subservient to a single thesis statement that I hope will enlighten the world…

This is a thing I do as a writer: I put what the characters are doing and thinking on the line and in the piece much more than me putting out a single idea or a philosophy for people to latch hold of. Now at this point in time, people are falling all over themselves to make sure they aren’t labeled this or that, and I’m fine with whatever anyone wants to take away from my movies. … I think one needs to ignore a lot of what certain characters do, and then say, well, what these characters are doing and saying, that’s what the author really feels. So then what you’re doing is bringing in your judgment of the author, and looking for evidence to support it, rather than looking at the material that’s at hand.

In the case of Dragged Across Concrete, I think it’s a very complex world; there are a lot of differing viewpoints that show, yeah, a lot of different people have different struggles. I understand why some people would say that [my films are conservative] — because there isn’t a clear didactic, if not pedantic, agenda at the fore of these pictures. But I’m writing stuff that I find compelling, and I’m not going to stop writing a scene, or change a character’s ethnicity, or remove a line of dialogue, because I think someone might interpret it in a certain way, or be offended by it. I’m writing what I find compelling…

One of Schager’s questions gets to the heart of liberal critiques of Zahler’s work: Do his films celebrate the protagonists, therefore validating their worldview, or are his films critiquing them, given how things spiral out of control for the protagonists? Zahler again maintains that he has no political dog in the fight. To the liberal mind, the very fact that Zahler chooses to provide full and humane character development to ‘racist’ White males (just as he does with the Black, third ‘lead’ character in Dragged) is itself suspect.

Bone Tomahawk was set in the Old West. Brawl was his first film in a modern-day setting, and Dragged is his second. As Zahler’s oeuvre grows in size, and Cinestate’s library of films and other media grows, alarmed liberals are sniffing a pattern. In The Hollywood Reporter, Stuart Miller writes:

[C]ritics have assailed Zahler’s films precisely for having an agenda: in the three films he directed, plus his [Puppet Master: The Littlest Reich] screenplay and a novel Wraiths of the Dying Land, he repeatedly has a White male protagonist saving White women and violently killing evil minorities. On the website Medium, Jacob Garfinkle writes, “It’s pretty clear that S. Craig Zahler has a formula for his fiction. Irredeemably evil minorities + damsel in distress threatened with sexual violence + heroic Aryan(s) + violent climax = jackpot!”

Some also argue Sparrow Creek humanizes alt-right militiamen, although [writer/director] Dunham says it was inspired by his own social anxiety and is about the “need for connection” and how that can lead isolated people to choose poorly. He adds, “I don’t have anything to do with the rest of the slate and if someone wants to lump me and Zahler together, well, we’re pretty different.”[10]

In his review for The Atlantic, David Sims (2019) observes that Dragged has “revived a strain of criticism that has long followed Zahler — criticism about whether his movies are more politically motivated than the director insists, and whether he’s sympathetic to the kinds of racist and sexist tropes that appear in his work.” Sims references how many (liberal) critics have asserted “that Zahler has a tendency to insert characters or lines of dialogue solely for the purpose of rebutting claims of racism or insensitivity.” From a perspective such as Sims’, “the particular one-dimensionality of characters of color, both good and bad, in his movies is a troubling pattern that’s difficult to ignore.”

“Many great works of art have been made about — and by — reprehensible people,” proclaims Todd Gilchrist (2019) in The Wrap. “But, thus far, Zahler has largely declined to discuss the ideas within his films and especially the views they espouse, leaving audiences to figure out for themselves if this and Brawl in Cell Block 99 are conservative screeds or just uncomfortably specific character studies for a certain White male point of view.” Gilchrist works himself into a stew, noting that “the director’s growing body of work may well resonate with exploitation fans as much as White nationalists,” before intoning with what sounds like a Commissar’s warning to Zahler: “But at a certain point, not clarifying or taking responsibility for any of what’s in your films means you’re responsible for all of it. And Zahler is not unique, creative or talented enough to keep audiences guessing much longer.”

“There’s a fine line between truth-telling and trolling,” writes liberal film critic Adam Nayman (2019), “and what Zahler is doing in Dragged Across Concrete seems closer to the latter. He’s protected to some extent by the pulp fiction format, which has a prerogative for obnoxiousness.” The final sentence of Nayman’s review contemptuously refers to Zahler as “a filmmaker who, more than anything, seems pleased to be getting away with something.”

In The Guardian, Charles Bromesco smells both fascism and trolling. “Tilt your head a little to the left,” he writes, “and the vision of Zahler as stealth fascist starts to come into focus. … Cinestate regularly positions White men as the last defense against a world of drugs, crime and rape.” Again, what bothers such critics the most is the potential trolling. “Each time Zahler transgresses, he provides enough internal counterargument to muddy anyone’s interpretation,” writes Bromesco. “There’s enough ammunition for either ideological side, leaving only an unsavory not-knowing.” Bromesco accuses Zahler of “saying one thing through his mouthpieces in the script, then saying the opposite to sow misgivings,” which leads Bromesco to conclude “there’s a word for people who consciously antagonize others and then claim that the mark is merely projecting their objections onto the antagonism: trolls. Zahler’s a troll par excellence, literally elevating the act to an art form. But at the end of the day, a troll is a troll is a troll is a troll.”

Richard Brody, one of the most unflinchingly anti-White film critics in the business, describes Dragged as a “reactionary” cinematic expression of “White-male rage”, a “trifecta of racism, sexism, and nativism.” As with a great many other critics, Brody sees the film as “an extraordinarily effective act of artistic trolling, a self-consciously brazen provocation that also covers its tracks with winkingly transparent gestures… Zahler hedges the movie’s racial stereotypes and sympathetic depictions of racism with details of plausible deniability that suggest Zahler’s awareness of how the movie is likely to be perceived.”

In his review for Vanity Fair, K. Austin Collins derides the film with a PC smugness matched only by his cognitive dissonance. Collins characterizes the anxiety the Ridgemans have of their daughter potentially getting raped by Black ghetto youth as an “illogically racist conclusion.” Regarding Ridgeman’s daughter Sara being repeatedly taunted by urban Black teenaged boys, Collins finds the entire scene, context and depiction incredulous. “Zahler’s premise,” he writes, “depends on our believing that Black kids in the neighborhood would really attack a White girl who’s the child of cops.” Collins assumes here that Sara’s repeated harassment refers to the same set of Black teens, which is refuted by Ridgeman’s wife Melanie in the aforementioned dialogue with her husband (“The ones she didn’t recognize.”) Furthermore, for Collins to assume a group of urban, Black, impulse-control-challenged youth would A) know that this White girl is the daughter of a cop, and B) would give two hoots about it and change their behavior if they did know, reveals more about Collins’ naivety than anything about Zahler. In our era of ubiquitous cell phone filming of anything and everything police do when interacting with the urban class (which is a central theme of Dragged), along with the widely acknowledged sociological phenomenon of post-Ferguson, post-BLM police disengagement, why would such Black youth treat the Ridgeman daughter any differently? They might do so, one can imagine, if there was a rational fear that Ridgeman would mete out justice while on duty, or even extrajudicially, but hasn’t that fear been nearly eradicated? This seems to be precisely what Zahler is pointing to with a string of dialogue between Ridgeman and his wife (about their fear for their daughter), with the altogether different course of action that Ridgeman actually pursues:

Brett: I’ll handle this.

Melanie: How?

Brett: There’s a way. But it’s not something that we’re gonna talk about… ever.

Melanie: Okay.

The audience is led to believe that Brett’s intention here is to punish the offending Black youth, by roughing them up, or worse. But, as the film shows, this is not what Brett does. Again, due to our ubiquitous cell phone era, Ridgeman pursues an entirely different course of action. This appears lost on Collins. Also, wouldn’t this sort of imagined behavior by Ridgeman (roughing up the youth being the more likely scenario) be precisely of the sort that Collins would himself be appalled by? In the BLM era, such youth are not chastened but emboldened.

Of Lurasetti having a mixed-race Black girlfriend, Collins drips with cynicism. “Lurasetti wants to propose to his (Black—don’t ask) girlfriend…” As so many other critics have done, Collins also accuses Zahler of trolling and bemoans the “wheels of diminished accountability” in Zahler’s film.

Regarding the same abovementioned anxiety the Ridgemans have about their daughter, and the Ridgemans’ conversation about moving to another (implied: Whiter) neighborhood, Jonathan Romney writes: “You pause to wonder whether Zahler is justifying the Ridgemans’ racism and their acceptance of it.” To someone of Romney’s stripes, it is simply beyond comprehension that a White person’s ‘racist’ attitudes towards urban Black males might, in fact, be due to real and lived experiences, rather than from blind and irrational prejudice.

As one would expect, garden variety National Review-type cuckservatives, in their reviews of Dragged, completely avoid interpreting the film through a race-realist lens. Kyle Smith is somewhat perplexed at Brett Ridgeman’s motivations. “The chief problem with the movie is that it’s hard to get a purchase on Brett… He’s not a wicked anti-hero who lacks any moral compass, but neither is he a good man forced into the abyss; the last straw for him is that his daughter gets a soda dumped on her, so he’s not exactly as well-motivated as Charles Bronson in Death Wish.” Smith completely misses the mark here. The whole point is that Ridgeman does not want to wait for his daughter to wind up like Dr. Paul Kersey’s daughter in Death Wish, and only then do something about it. Smith shores up his NR bona fides when he adds:

Movies with racial themes these days have a cloud of panic about them and scramble desperately to signal their virtue. This one, which gives racists plenty to snicker at only to pull the rug out from under them, is much sneakier. Instead of drawing its Black characters as hapless victims, it suggests they have more agency than anyone knows.

Also writing in National Review, Armond White (who is himself Black) surprisingly labels Dragged a “conservative action movie with spiritual depth… a story of urban chivalry”, a film where the protagonists Ridgeman, Lurasetti, and Henry/Slim, are “in constant search of spiritual satisfaction”, and eventually “come together in their alienation.” In contrast to the many liberal White film critics who moan (and virtue-signal) over the supposed one-dimensionality of Henry’s character, White actually praises Henry’s characterization. “It is Zahler, unlike other modern directors making noise about race and representation,” White writes, “who introduces the most credible Black male movie character this decade.”

Conclusion

Dragged Across Concrete continues many of the themes of Brawl in Cell Block 99, particularly the plight of White men in a rapidly changing, multicultural America, and the moral relativism that progressivism has engendered across the political spectrum. In a very incisive review at Quillette, David G. Hughes writes:

The difficult truth about Dragged Across Concrete is that it’s neither progressive nor reactionary; liberal nor conservative. Rather, it exists as a thorn in all of our sides, refusing to offer even the reassuring catharsis of a redemption parable…

[A] film as resolutely apolitical as this one resonates with contemporary political discontents. Zahler has his finger on the cultural pulse, even if it’s not entirely clear if he believes there’s a heartbeat worth saving. As the violent narrative closes in on its inevitable denouement, Lurasetti says, “I hope I am not remembered for this mistake.” But we know he is lost because the culture has commanded it. In a cultural moment that has seen reputations destroyed by a single tweet, each transgression can become the entirety of a person’s character. Beneath the car chases, shoot-outs, and smart dialogue in Dragged Across Concrete is an elegy, not for the passing of time (this isn’t a nostalgic film), but for those left behind when the cultural baton is passed from one generation to the next. The hands that built the nation are now tainted, their flaws have been exposed and denounced, and swathes of our fellow citizens have been condemned as unclean rabble-rousers. Here is a film that speaks to this cultural tragedy in the shape of two flawed cops, resigned to a world that despises them but doing their awkward and imperfect best to stay afloat and do the right thing as they understand it.

Henry, his mom, & White male masseuse.

To revisit the Lion analogy a last time, there is no room for the likes of Ridgeman and Lurasetti in today’s progressive culture, a culture which regresses, inch by inch, to the law of the jungle. The arc of Henry’s journey – from ghetto to prison to immense wealth, sole-survivor status, and readiness to ‘hunt some lions’ — can be interpreted as satire on both the adjunct, and relatively new, phenomenon of ‘Black privilege’, and perhaps also as a troll (a la Chuck Palahniuk’s 2018 novel Adjustment Day) with its intimations of Blacks inheriting the Earth through an imagined and long-suppressed, syncretic law-of-the-jungle knowledge. That Henry lives in a clean, White, modernist, and proverbial castle on the water — instead of having financially imploded, the way so many Black criminals, athletes and rappers do — is, proportional to the degree it is unrealistic, likely a troll. The same is true of Zahler’s depiction of Henry as the film’s moral center, who even sends a cop’s widow a small share of the stolen gold (a precious metal throwback to pre-industrial times) in order to honorably comply with the dying’s wishes, a scenario that, in and of itself, stretches credulity.

We live on the cusp of a new age, where Persons of Color will increasingly exercise their newly gained power over Whites, ruthlessly meting out ‘social justice’ in perpetuity, as revenge for how they imagine Whites previously lorded power over them. With no socially sanctioned outlets for racialist identity formation or collective promotion of such group-based racial interests, Whites may increasingly resort to a reactionary nihilism of the type symbolically represented in Brawl and Dragged. Likewise, the cinematic art of trolling is one of the few clandestine means of articulating this reactionism in an increasingly liberal, intolerant, and anti-White culture.

References

- Bramesco, Charles. “Trolled Across Concrete: Why Mel Gibson’s New Film is a Curious Provocation,” The Guardian, March 23, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2019/mar/22/dragged-across-concrete-mel-gibson-troll-new-film-provocation

- Brody, Richard. ““Dragged Across Concrete,” Reviewed: A Stylish, Repugnant Crime Thriller Starring Mel Gibson,” The New Yorker, March 19, 2019, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/the-front-row/dragged-across-concrete-reviewed-a-stylish-repugnant-crime-thriller-starring-mel-gibson.

- Collins, K. Austin. “Dragged Across Concrete Is at Its Best When It’s at Its Worst,” Vanity Fair, March 25, 2019, https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2019/03/dragged-across-concrete-review.

- Edelstein, David. “Dragged Across Concrete Is Your Basic, Boneheaded Right-Wing Action Movie”, Vulture, March 22, 2019, https://www.vulture.com/2019/03/movie-review-dragged-across-concrete-2019.html

- Hughes, David G. “Dragged Across Concrete – A Review,” Quillette, March 23, 2019, https://quillette.com/2019/03/22/dragged-across-concrete-a-review/.

- Kael, Pauline. “Dirty Harry: Saint Cop,” The New Yorker, January 15, 1972, reprinted at https://scrapsfromtheloft.com/2017/12/28/dirty-harry-saint-cop-review-by-pauline-kael/

- Gilchrist, Todd. ““Dragged Across Concrete” Film Review: Vince Vaughn and Mel Gibson Are Dirty Cops in a Potentially Trolling Thriller,” The Wrap, March 22, 2019, https://www.thewrap.com/dragged-across-concrete-film-review-vince-vaughn-mel-gibson/.

- Miller, Stuart. “How a “Populist” Film Studio Is Turning Rage and Violence Into Revenue,” The Hollywood Reporter, January 28, 2019, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/how-cinestate-film-studio-is-turning-controversial-topics-revenue-1178338.

- Nayman, Adam. “‘Dragged Across Concrete’ Pushes Buttons Until They Break,” The Ringer, March 21, 2019, https://www.theringer.com/movies/2019/3/21/18274818/dragged-across-concrete-mel-gibson-vince-vaughn-review.

- Romney, Jonathan. “Film of the Week: Dragged Across Concrete,” Film Comment, March 22, 2019, https://www.filmcomment.com/blog/film-of-the-week-dragged-across-concrete/.

- Schager, Nick. “The Hollywood Filmmaker Making Movies for the MAGA Crowd,” The Daily Beast, March 17, 2019, https://www.thedailybeast.com/s-craig-zahlers-dragged-across-concrete-starring-mel-gibson-the-hollywood-filmmaker-making-movies-for-the-maga-crowd.

- Schwartzel, Erich. “Making Movies in the Trump Era for the Audience Hollywood Ignored,” The Wall Street Journal, May 15, 2018, http://archive.fo/w7E9K.

- Simek, Peter. “Dallas Sonnier’s Hollywood Ending,” D Magazine, Dec 2016, https://www.dmagazine.com/publications/d-magazine/2016/december/dallas-sonniers-hollywood-ending/.

- Sims, David. “Dragged Across Concrete and the Sloppy Provocations of S. Craig Zahler,” The Atlantic, March 25, 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2019/03/s-craig-zahler-dragged-across-concrete-films/585424/.

- Smith, Kyle. “Mel Gibson’s Shocking New Role,” National Review, March 20, 2019, https://www.nationalreview.com/2019/03/dragged-across-concrete/.

- Stern, Marlow. “Mel Gibson’s New Police Brutality Movie Is a Vile, Racist Right-Wing Fantasy,” The Daily Beast, September 3, 2018, https://www.thedailybeast.com/mel-gibsons-new-police-brutality-movie-is-a-vile-racist-right-wing-fantasy.

- Tobias, Scott. “The Director Who Doesn’t Care What You Think of His Movies,” The Ringer, March 22, 2019, https://www.theringer.com/movies/2019/3/22/18276913/s-craig-zahler-dragged-across-concrete-brawl-in-cell-block-99.

- White, Armond. “Dragged Across Concrete: A Conservative Action Movie with Spiritual Depth,” National Review, March 22, 2019, https://www.nationalreview.com/2019/03/dragged-across-concrete-conservative-action-movie/.

[1] In her 1972 review of Dirty Harry, Pauline Kael infamously referred to the film as “fascist” and “deeply immoral”, a “right-wing fantasy of that police force as a group helplessly emasculated by unrealistic liberals.” The pendulum swing back towards a distinctively liberal spin on the vigilante film genre stretches back to the anti-Reagan hysteria of the 1980s, through films such as The Star Chamber (1983).

[2] For more on Cinestate’s eclectic business model, see Miller (2019). For the fascinating backstory of how Sonnier turned extreme personal tragedy (the separate murders of both of his parents) into the fuel to put all his personal finances on the line towards making Bone Tomahawk, see Simek (2016).

[3] The irony of Mel Gibson’s character being caught by video, given Gibson’s own personal history of having audio-recording capture his rants, is surely not lost on Zahler. Such is likely another instance of Zahler’s trolling.

[4] If interpreted literally, the idea of cops being underpaid requires some suspension of disbelief. However, this may be intended to figuratively represent the hallowing out of White, lower middle-class American wages.

[5] As a nonreligious Jew, Zahler may see himself as “White.” Zahler’s depiction of Denise as a successful, highly-paid, White collar manager contrasts with Lurasetti as a not highly-paid, not-promoted cop, which may be a commentary on how, in the era of SJW corporations, Persons of Color are to be hired and promoted before Whites. That Denise is eloquent and dating a White cop who makes less than her may also be trolling on the part of Zahler. Evidence for trolling is when Lurasetti mentions that Denise “only shops at organic stores, specializing in assuaging guilt.” With respect to Jewish stereotypes, further evidence that Zahler is willing to troll may be found in Puppet Master: The Littlest Reich (2018), an indie horror-comedy about Nazi puppets, which Zahler wrote the screenplay for. In one scene, for instance, the “heroes try to lure these anti-Semitic monsters out of hiding by lighting a menorah” (Tobias).

[6] This dialogue expressing the Ridgemans’ fear of their daughter getting raped by Black teenagers is not only a rational fear within the context of the film (and for Whites living among urban Blacks in general), but may be a troll regarding an infamous secret recording Mel Gibson’s former girlfriend Oksana Grigorieva made of him. “You look like a fucking pig in heat,” Gibson can be heard yelling at her. “If you get raped by a pack of niggers, it’ll be your fault.”

[7] In the film’s final act, as they prepare to rob the Vogelmann crew, Ridgeman and Lurasetti don Black, full face masks similar to the ones that the Vogelmann crew wear, leading to the film’s working reality that all of the White male primaries don similar Black masks.

[8] In his review of the film, liberal critic Marlow Stern refers to this bit of dialogue as “objectionable nonsense.”

[9] From this perspective, the psychopathic villains assume not the form of Nazi caricatures, but rather totalitarian Leftists.

[10] For unknown reasons, Garfinkle has apparently deleted his article (which was titled “Is S. Craig Zahler a White Supremacist?”) from Medium. The link for the article now says: “The author deleted this Medium story.” Other facets of Zahler’s creative output point to trolling being a likely motivator for him, such as his writing for Fangoria and the dark apocalyptic tropes of his heavy metal side projects. Tobias notes: “While cranking out screenplays, Zahler turned out three heavy metal albums with his friend Jeff Herriott as one half of Realmbuilder, and played drums and contributed songwriting to the Black metal band Charnel Valley. Gently described, these bands are an extension of Zahler’s interest in dark fantasy and world-building, with ominous song titles like “Advance of the War Giants,” “The Beast of Six Thousand Bones,” and “Carry Their Bodies to the Horizon.””

Another movie released in response to the leftist shift of the 60s that even preceded Dirty Harry by a year was Joe staring Peter Boyle. I never see it mentioned anymore. It did very well considering its low budget and plot.

Peter Boyle is jooish. Consider the source. Certain the credits read like a bar mitzvah guest list.

“Joe” (1970) has long been on my radar screen, but I have yet to see it. A surprising number of lib film critics like it (80% RT score). A BluRay version of the film came out in the past 12 months, so I should be able to get my hands on it now.

I appreciate Mr. Zahler’s work, and I understand his need for a certain amount of crypsis in his work and when being interviewed, but his protestations that he is not political and just lets his stories evolve through his characters is frankly bs. Who the hell is deciding on his characters other than him? So he is either our guy, or he has found a market niche and is exploiting it.

“We live on the cusp of a new age, where Persons of Color will increasingly exercise their newly gained power over Whites, ruthlessly meting out ‘social justice’ in perpetuity”

Good review, thanks. But I don’t think the above is defensible. History is written by its protagonists’ actions. Persons of Color have as much or as little power as is granted them by the System, the vitality of which depends on whites.

Once Whites are genocided off colored people will no longer have any power or value to their jooish slave masters.

Agree 100%. I can’t figure out whether white nats really hate blacks for primitive reasons or are just too dumb to figure out that blacks, Hispanics, ‘native Americans’ et al. are mere chesspieces for the plutocrats. Jeez, get a friggin clue or shut up! Here’s one clue: average black net worth is 1/20 of white.

“pulp horror and dark fantasy (e.g., H.P. Lovecraft, Robert E. Howard, Edgar Rice Burroughs)”

The last author is out of the given category by several light years.

Thanks to Mr. West for drawing attention to Dallas Sonnier’s real-life drama. An inspiring tale of fortitude in the face of adversity.

https://www.dmagazine.com/publications/d-magazine/2016/december/dallas-sonniers-hollywood-ending/

I think there is a good market for 1950s Disney-style ‘wholesome’ entertainment. Movies that presume and reinforce Christian and Anglo-Saxon bourgeois values, where people do not swear every sentence, where politically incorrect behavior is presented as normal. The right is just too stupid and passive to conceive of acting with “chutzpah” in the face of liberal contempt.

“expressed, ironically, through unsympathetically depicted characters — for example, Falling Down”

I thought M Douglas was a sympathetic character.

These film studios would rather make $90 m and be politically correct than make $200m and be politically incorrect. We have to wonder what proportion of the people in this industry approve of this policy, and what proportion feel they just have to go along with it, but would actually prefer the $200m given a choice.

I found MD’s character in “Falling Down” sympathetic as well, however I believe director Joel Schumacher attempted to portray him, in the end and for the audience, as a ‘bad guy’, perhaps misunderstood, but still a bad guy.