Against Mishima: Sex, Death and Optics in the Dissident Right

“One learns from Confessions of a Mask how Mishima put “Circassians” (white boys) to the sword by the dozen in his dreams.”

Henry Scott Stokes, The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima

“Mishima is more a figure of parody than a force of politics.”

Alan Tansman, The Aesthetics of Japanese Fascism

I read with great interest Guillaume Durocher’s recent Unz Review article on Yukio Mishima’s commentary on the Hagakure, the eighteenth-century guide to Bushido, or Japanese warrior ethics. I rate Durocher’s work very highly, and as someone who once shared his interest in Mishima, and Japanese culture more generally, I expected the piece to be well-informed, insightful and provocative. Much as I was intrigued by Durocher’s piece, I think the Dissident Right would benefit from an alternative view of Mishima, and perhaps also the subject of Japanese culture in the context of European rightist sensibilities, especially when right-wing treatments of Mishima other than Durocher’s (which is suitably measured in the assessment of Mishima’s fiction) tend towards hagiography. In the following essay, I offer not necessarily a rebuttal or rebuke of Durocher, but an alternative lens through which to view the Japanese author, his life, and politics. Since a movement’s choice of heroes can have an impact on its spirit and ethos, the following should be considered an attempt at spiritual ophthalmology, or the bringing of certain perspectives into clearer focus. This clearer focus, I argue, can only lead to the conclusion that Mishima was a profoundly unhealthy and inorganic individual who should be regarded as anathema to European nationalist thought.

My first introduction to Yukio Mishima came several years ago in the form of a recording of a 2011 lecture delivered in London, by the late Jonathan Bowden, at the 10th New Right meeting. Bowden was an exceptional orator, yet to find an equal in the current crop of dissident right leaders. In fact, as we move further and further into patterns of YouTube-based “content producing” I fear that oratory of Bowden’s type may become an increasingly rare art. One of Bowden’s great strengths as a speaker was the ability to take dense topics and biographical overviews and reduce them to an hour or so of dynamic, entertaining, and extremely accessible commentary. Those in the audience, or listening in other forms, found it impossible for their attention to wander. A downside to Bowden’s oratory was that it didn’t translate quite as well onto paper, often following Bowden’s stream of consciousness rather than more logical and structured progression, with the result that one laments that Bowden didn’t focus also on a more formal type of scholarship that would surely have constituted a monumental and lasting bequest to the movement he devoted so much to. As it stands, recovering Bowden’s legacy has for the most part been the task of tracking down lost recordings of his speeches, a task that Counter-Currents have admirably taken the lead in.

Prior to listening to Bowden on Mishima, I had already established an interest in Japanese history and culture. I trained for several years in jiu-jitsu, spent a great deal of time in my early 20s reading the works of D. T. Suzuki and Shunryu Suzuki on Zen Buddhism (the former also had some interesting and sympathetic things to say on National Socialism and anti-Semitism), and Brian Victoria’s 1997 Zen at War remains one of the most interesting works on the history of religion and warfare I’ve yet had the pleasure to read. Somehow, however, Mishima escaped my attention until Bowden’s lecture, which really offered only the most raw and basic of introductions to the man. Bowden presented Mishima as a rightist thinker but never quite explained why. He indicated that Mishima had some relevance for the European right but couldn’t articulate how. The lecture only clumsily situated Mishima within near-contemporary Japanese culture, and Bowden himself evinced equivocation and incomprehension on the reasons why Mishima undertook his now infamous suicidal final action. Who was Mishima? Why was he relevant? In a bid to follow up these loose ends, and trusting Bowden that the effort would be worthwhile, I spent around a year making my way through Mishima’s fiction, biographies, scholarship, and other forms of commentary on Mishima’s life and death. The result of my research was a deluge of notes, many of which will now make their way into this article, and profound disappointment that such a figure should ever have been promoted in our circles.

Explaining how and why Mishima came to be promoted in corners of the European Right requires that one confront what could be termed “the Mishima Myth,” or the vague and propagandized outlines of what constitutes Yukio Mishima’s biography and presumed ideology. The Mishima Myth runs something like this:

Yukio Mishima was a gifted and prolific Japanese author and playwright who became profoundly disillusioned with the political and spiritual trajectory of modern Japan; influenced by Samurai tradition and Western thought, especially the philosophy of Nietzsche, he embarked on a program of radical self-improvement; he took up bodybuilding and formed his own 100-strong private army — the Shield Society; he led this army in an attempted coup at a military base, taking a very senior officer hostage, and demanded that all troops follow him in rejecting the post-war constitution and supporting the return of the Emperor to his pre-war status as deity and supreme leader; finally, rejected and ridiculed by the troops, he took his life via seppuku, ritual disembowelment in the tradition of the Samurai.

Occasionally, for added effect, rightist promoters of Mishima will add that he wrote a 1968 play titled My Friend Hitler, which, despite the provocative title, is politically middling, and has been interpreted as anti-fascist as often as it has been as fascist. Taken together, one supposes that the relevant factors here are that Mishima was an authoritarian, monarchist “Man of Action” who seized control of his own life and attempted to divert his nation away from empty consumerism (cue applause). Thus, in the Mishima Myth, rather than focusing on his actual writings on fascism and politics (which are in any event very few in number), Mishima’s ideology is read from selected chapters of his life, especially his final actions. Mishima becomes a man of the right because he was Mishima, because of what he did. This, so the narrative goes, is why he should be relevant to us.

A critique of the Mishima Myth is therefore necessarily ad hominem, since there is a glaring absence of ideas to argue against and since the myth is merely a composite of slices of edited and heavily sanitized biography. Despite an abundance of English-language biographies, rightist promoters of Mishima rarely engage in serious exploration of Mishima’s life, preferring to focus on hagiographic presentations of selected episodes, especially their interpretation of the dramatic death. This should be the first cause of caution, and it was certainly mine. The primary reason for this evasion, as I was to find out, is profound embarrassment, since Mishima’s life is thin on right-wing politics, or for that matter politics of any description, and rather heavy on homosexual sadomasochism (which is far from the only questionable aspect of Mishima-ism). But we are getting ahead of ourselves. Let’s start at the beginning.

Yukio Mishima was born Kimitake Hiraoka on January 14 1925, into an upper middle-class family. One of the first things that struck me about Mishima’s life, and especially his childhood, is that it has attracted swathes of psychoanalysts,[1] the reason being that he is an important and visible example of what these writers perceive to be the link between oppressive and abusive childhoods, latent homosexuality, sadism, masochism, and authoritarian and fascist politics. Indeed, if one makes the argument that Mishima was in fact a fascist, then one begins to consent to some of the central theses of the Frankfurt School. Mishima certainly had a strange and psychologically distorting childhood, and I concur with Sadanobu Ushijima’s conclusion that it resulted in Mishima suffering most of his life from a personality disorder involving “recurrent episodes of depression with severe suicidal preoccupation.”[2]

According to Henry Scott Stokes, in my opinion Mishima’s best biographer as well as being the only Westerner invited to his funeral, almost as soon as Mishima was born his grandmother (Natsuko) “resolved to take personal responsibility for his upbringing and virtually kidnapped the little boy from his mother,” raising the child almost entirely in her sickroom.[3] Natsuko brought up Mishima “as a little girl, not as a boy,” and he was forced to stay inside, was prohibited with playing with most of his environment, and was told to be almost completely silent due to his grandmother’s complaints of constant head pain.[4] After some years, his mother was permitted to take him outside, but only when there was no wind.[5] There is some suggestion that he was beaten, or otherwise severely psychologically abused, with the result that he suffered a sequence of psychosomatic illnesses involving the retention of urine. There is also some suggestion of sexual abuse or “obscene” treatment at the hands of his grandmother’s nurse. Quasi-incestuous closeness in indicated by his later description of his grandmother as a “true-love sweetheart”, and on his death his mother described him as her “lover.”[6] Mishima was generally regarded by those around him as “an unusually delicate child.”[7]

In keeping with scientific studies strongly suggesting that dressing, or otherwise treating, young boys as girls can induce homosexuality,[8] and studies showing that homosexuals are more likely than the sexually normal to be predisposed to “brutal” violence[9] (to say nothing of what anecdotally appears to be a disproportionate preponderance of homosexual serial killers and cannibals), Mishima would later write in his semi-autobiographical Confessions of a Mask (1949) that he had homosexual fantasies from a young age and that many of these were sadistic in nature. At this point I should pause and concede that the British “anti-Fascist” collective operating as Hope Not Hate have described me as perhaps the most “homophobic” “far right commentator” in the Dissident Right, as well as simplifying my perspective as framing “homosexuality and modern conceptions of gender as socially constructed as a symptom of societal decay, and LGBT+ rights as a tool of a Jewish conspiracy to undermine white society. This vein of thinking sometimes even results in open calls for the expulsion or violent eradication of LGBT+ people.”

This may or may not be an entirely accurate representation of my views, but the point I want to make here is that my critique of Mishima isn’t based on his homosexuality qua homosexuality, since the argument could be made by some that a homosexual fascist is still a fascist (though such arguments could be easily problematized and I will later critique his “fascism” in and of itself). Piven remarks that there has long been a “Mishima cult” in France (perhaps Durocher can confirm), adding “though his following outside Japan consists largely of gay populations who champion him.”[10] My argument against the Mishima myth is mainly that if key aspects of his biography, including the death, are linked significantly more to his sexuality than his politics, then this is grounds to reconsider the worth of promoting such a figure, already non-White and with no significant Western cultural impact, within the Dissident Right.

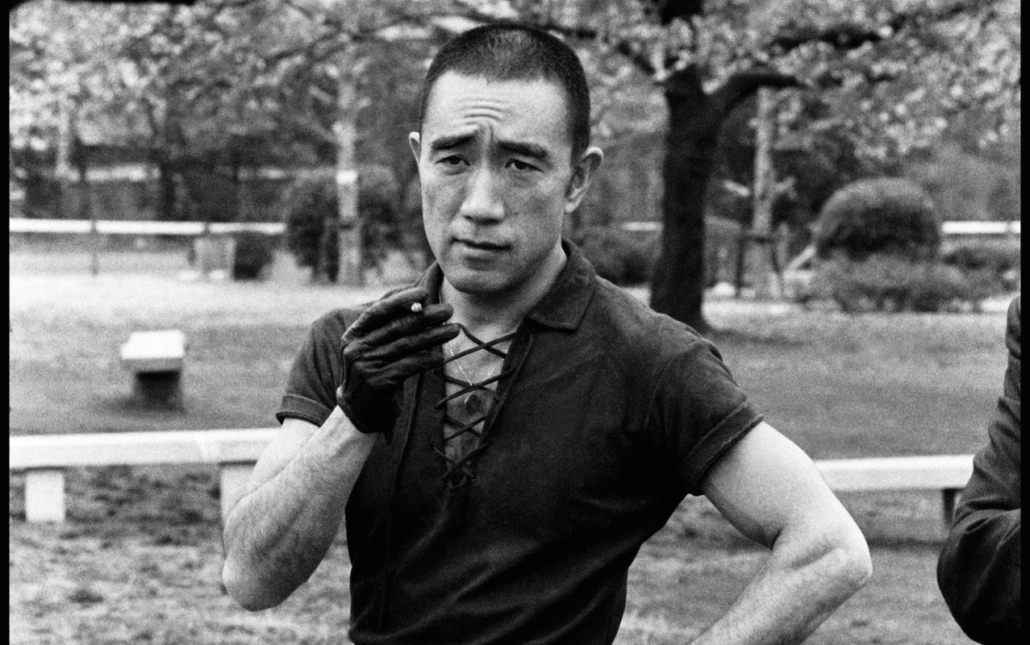

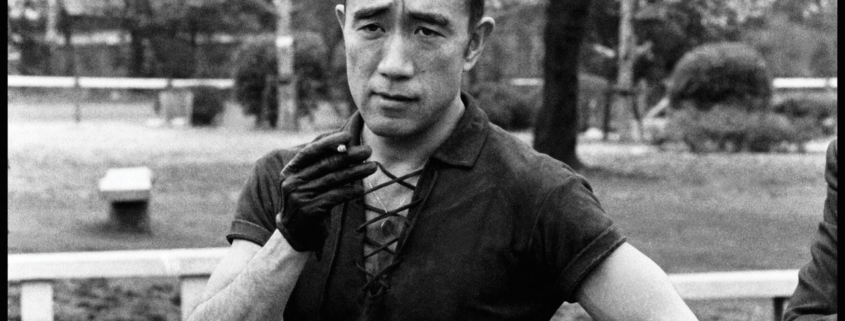

Mishima was “eternally excluded from the lives of ordinary men and women,” and developed early fantasies about taxi drivers, bartenders, but especially soldiers.[11] He was particularly fixated on the idea of dying soldiers and death generally, and “the violent or excruciatingly painful death of a handsome youth was to be a theme of many of his novels.”[12] In childhood, Mishima enjoyed playing dead, and he had eroticized notions of suicide from early adolescence. In his own words, he had a “compulsion toward suicide, that subtle and secret impulse.”[13] His first erotic experience appears to have been masturbating to a print of Guido Reni’s St. Sebastian, which depicts the semi-nude and bleeding saint bound to a tree and impaled with arrows. Mishima would later explain that he “delighted in all forms of capital punishment and all implements of execution so long as they provided a spectacle of outpouring blood.”[14] Stokes comments that “In Mishima’s aesthetic, blood was ultimately erotic.” Mishima fantasized about wounded, dying soldiers, imagining “I would kiss the lips of those who had fallen to the ground and were still moving spasmodically.”[15] He day-dreamed about execution devices studded with daggers, designed to shred the bodies of young men, and had a “fantasy of cannibalism” in which he fed on an athletic youth who had been “stunned, stripped, and pinned naked on a vast plate.”[16] Jerry Piven observes that Mishima’s fiction is replete with “innumerable fantasies of raping and killing beautiful young boys, of scenes of masturbating to images of slain men, of ceaseless loathing for despicable women.”[17]

St. Sebastian by Guido Reni (c. 1625)

In Deadly Dialectics: Sex, Violence and Nihilism in the World of Yukio Mishima (1994), Roy Starrs comments:

Few writers since the Marquis de Sade himself have made a more public and provocative “performance” of their “perverse” sexuality. … He found himself aroused by pictures not of naked women but of naked men, preferably in torment. Again he finds that homosexual pleasure is inextricably linked, for him, with sadistic pleasure, and he indulges in the most outrageous fantasies of managing a “murder theatre” in which muscular young men are slowly tortured to death for his amusement.[18]

Mishima read both Freud and the works of the Jewish sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld, and concurred with the latter (also a homosexual and transvestite) that pictures of the dying St. Sebastian were a favorite among homosexuals, with Mishima himself arguing that “the homosexual and sadistic urges are inextricably linked.”[19] Far from the image of the austere Samurai, as he approached middle age the increasingly bipolar Mishima was known to dance in gay bars with a 17-year-old drag queen,[20] and once flew to New York solely for the purpose of finding a White man who would be sexually “rough” with him. His former lovers recall how he “liked to pretend he was committing seppuku,” making them watch, before asking them to stand over him with a sword as if about to behead him. He would pull out a red cloth, that he would pull across his abdomen explaining this was his “blood and guts.”[21] Mishima once described himself as “strangely pathetic.”[22] Durocher may well be correct in his review of Mishima on the Hagakure that “Above all, Mishima would have men live full, worthy, and noble lives,” but readers should by now be aware of why I felt an alternative lens needed to be introduced to our perspective.

A theory thus presents itself that Mishima’s carefully orchestrated death was a piece of homosexual sadomasochist theatre rather than anything political, let alone fascistic or in the tradition of the Samurai. In order to parse this question more fully, it’s necessary to examine Mishima’s politics and spirituality, or what can at least be discerned in that direction.

One of the remarkable things about Mishima is that he seems hardly political at all. His fiction, denounced by early critics of all political hues as full of “evil narcissism” possessing “no reality,” is almost entirely devoid of ideology. (Durocher appropriately mentions how he tried to, and wanted to, like Mishima’s novels but couldn’t.) As such, Mishima is a pale shadow of ultra-nationalist literary contemporaries like Shūmei Ōkawa, Hideo Kobayashi, and Yasuda Yojūrō. Confessions of a Mask, his most autobiographical text and a style of novel (shishosetsu) that Kobayashi especially loathed as ‘popular’, “had nothing to say in it about political events that had influenced his life. … He was regarded as apolitical by his contemporaries.”[23] He was neither politically involved nor possessed of any real depth of feeling on political matters until the 1960s, when he was around 40 and becoming increasingly pessimistic and depressed — mainly because he was ageing and was disgusted and horrified by old age.[24] In his commentary on the Hagakure, Mishima would inflect his own anxieties about ageing and his own predilection for youthful suicide fantasies by telling his readers they should live for the moment and be content with a short life, and one gets the sense of personal inflections again when he informed his readers that “homosexual love goes very well with the Way of the Warrior.”[25] Otomo remarks that Mishima’s relationship to the Hagakure was simply peculiar and largely artificial, pointing to better, more authentic, examples of Bushido ethics and exploits such as Budoshoshinshu and the Kōyō Gunkan, and remarking on the Hagakure:

Ironically enough, the text is evidence of the absence of the code. It is an empty style that can be borrowed by anyone at any time of history and it no longer signifies a core culture of an Oriental entity called Japan. In fact, it has never signified as such except in one man’s nostalgia.[26]

In reality, and despite his self-presentation as the embodiment of the Hagakure, Mishima was strangely un-Japanese, something remarked upon by Stokes (“he was remarkably un-Japanese”)[27], who met him several times, and as evidenced in various aspects of Mishima’s life. Ryoko Otomo observes that, in a departure from the Zen Buddhism of the Samurai, Mishima, “was an affirmed atheist.”[28] What Mishima did in fact see in Zen and the Hagakure, so far as can be determined from his fiction and statements to journalists, was a dark and profound nihilism — something that any Zen master, including D. T. Suzuki who in one of his seminal texts has a chapter titled “Zen is not Nihilistic”, would argue is anathema to authentic Zen conceptions of “the Void.” When he became financially successful, Mishima set about building a large, Western-style, “anti-Zen” house, and Zen masters he associated with later remarked Mishima made “no profound study of philosophy.”[29] Mishima knew nothing of nature, being a decadent urbanite, and was unlike many Japanese in being ignorant of the most basic botany. Once, when accompanying a friend in the countryside, he was shocked and confused at the noise of frogs.[30] He once told reporters that his average day was spent with gym activity followed by lounging around a house regarded by his neighbors, and even its architect, as “gaudy,” “in jeans and an aloha shirt.”

Mishima went through with a hasty marriage of convenience to satisfy his dying mother, fathering two children that, in the style of the worst ghetto-dwellers, he was largely absent from. In fact, in several of his novels, especially Forbidden Colors which is replete with what Stokes calls “morbid sexuality,” he expresses contempt for children, families, and the normal, non-homosexual familial structure that is the backbone and future of all societies and civilizations:

Go to a theater, go to a coffeehouse, go to the zoo, go to an amusement park, go to town, go out to the suburbs even; everywhere the principle of majority rule is lording about in pride. Old couples, middle-aged couples, young couples, lovers, families, children, children, children, children, children and, to top it off, those blasted baby carriages—all of these things in procession, a cheering, advancing tide.

By contrast, as a homosexual, Mishima nurtured fantasies of himself as a member of an elitist minority.

Ideologically, Mishima was clumsy and confused at best. He believed that fascism and Freudian psychology were ideologically related,[31] and believed in resurrecting a Japanese imperialism that would make room for parliamentary democracy.[32] He insisted, meanwhile, that “fascism will be incompatible with the imperial system.” Moreover, he argued that Japanese right-wingers “did not have to have a systematised worldview,” perhaps because he had none himself, and that they “nevertheless have nothing to do with European fascism.”[33] By the early 1960s, Mishima was a writer of decadent romantic fiction so politically weak, and tendentiously left-wing, that he was targeted with death threats by right-wing paramilitaries.[34] Eventually, some time in the late 1960s and despite having no real depth of feeling for Shinto religion, Mishima decided that it would be a good idea if the Emperor was returned to his pre-war status as a deity, prompting Sir John Pilcher, British Ambassador to Japan to declare Mishima’s fantasy of placing himself “in any relationship to the Emperor” as “sheer foolishness.”[35] Mishima, of course, never explored the Emperor’s role in World War II in any depth, and his chief fixation appears solely to have been the decision of the Emperor to accede to Allied demands and “become human.” Although Mishima became increasingly vocal on this issue, and even started taking financial donations from conservative politicians to establish a small paramilitary grouping consisting of lovers and fans, “he never defined his positions clearly,” and was so poor at articulating his ideas to troops during his coup attempt that he was simply laughed at by gathered soldiers.[36] Whether or not Mishima was fully sincere is, of course, another matter, though his suicidal coup attempt came very shortly after literary career declined so rapidly that friends wrote to him “telling him that suicide would be the only solution.”[37] Suicide in Japanese culture is of course also crucial to this discussion and will be explored below.

Mishima’s purported militarism is worthy of some attention. I come from a military family, and have many friends in the military. One of the things that’s always irritated and amused me is the difference between how actual service personnel discuss themes such as “being a warrior” or combat more generally in comparison to military fantasists. Among the former, there always exists a wry, sober, even bittersweet outlook. Among the latter, one is apt to find much talk of glory and conquest, but little action. Mishima was surely a military fantasist, who even by his own admission had a sexual fetish for the white gloves worn with the Japanese uniform,[38] and lied during his own army medical exam during the war in an effort to avoid military service: “Why had I looked so frank as I lied to the army doctor? Why had I said that I’d been having a slight fever for half a year, that my shoulder was painfully stiff, that I spit blood, and that even last night I had been soaked by a night sweat? … Why had I run so when I was through the barracks gate?”[39]

When the bombs fell during the war, Mishima recalled, “that same me would run for the air-raid shelters faster than anyone.”[40] Stokes suitably comments that “had he served in the army, even for a short while, his view of life in the ranks would have been less romantic, later in life,” but that instead “Mishima stayed home with his family, reading No plays, the dramas of Chikamatsu, the mysterious tales of Kyoka Izumi and Akinari Ueda, even the Kojiki and its ancient myths.”[41] When he eventually formed his own paramilitary organisation, he dressed them in “opéra bouffe uniforms which incited the ridicule of the press,” and Starrs comments: “He was no more a true ‘samurai’ than he was a true policeman or airforce pilot, in whose garb he also had himself photographed. The ‘samurai’ image was simply one of Mishima’s favourite masks — and also one of his most transparent.”[42]

One could add speculations that Mishima’s military fantasies were an extension of his sexual fixations, including a possible attempt to simply gain power over a large number of athletic young men. But this would be laboring an all-too-obvious point. More soberly, one could merely point to the ridiculous notion of a military coup being led by a bipolar, draft-dodging shut-in (Hikikomori) who, when confronted during the action itself, witnessed the beginning and end of his fighting career when he hacked frantically at a handful of unarmed men with an antique sword. The Jewish academic and Japan scholar Alan Tansman might well be a sexual pervert himself, but it’s difficult to disagree with his assertion that “Mishima is more a figure of parody than a force of politics,”[43] and attempts to link Mishima with our worldview only provide further grist for the Jewish mill.

Since Mishima’s writings and actions are politically opaque at best, it is little wonder that most attention from his propagandists has focused on the dramatic and quasi-traditional method of suicide, which is often portrayed as representing the utmost in honor, masculine courage etc. Such accounts, of course, normally omit the fact Mishima rehearsed his suicide for decades in the form of gay sex games, and was essentially a gore fetishist. A broader problem exists, however, in the nature of Western appraisal of seppuku, and suicide in Japanese culture more generally. The most enlightening piece of work I’ve read in this sphere has been that of the late Toyomasa Fuse (1931–2019), Professor Emeritus at York University and probably the world’s leading expert on suicide among the Japanese. In Suicide and Culture in Japan: A Study of Seppuku as an Institutionalized Form of Suicide, Fuse explains that suicide in Japan essentially originates from a servile position within a highly anxious and neurotic society. Needless to say, this is far from healthy and praiseworthy behavior. He describes seppuku as a form of “altruistic suicide” and an expression of “role narcissism,” it being a

Response to a continued need for social recognition resulting from narcissistic preoccupation with the self in respect to status and role. … Many Japanese tend to become over-involved with their social role, which has become cathected by them as the ultimate meaning in life. … Shame and chagrin are so extreme among the Japanese, especially in a perceived threat to loss of social status, that the individual cannot contemplate life henceforth.[44]

There is little question that seppuku had a place among the samurai, but the actual nature of its practice over time was complex and was successively reinterpreted, alternating between a voluntary way of recovering honor, and a form of capital punishment (peasants, meanwhile, were simply boiled alive). It also alternated in form, involving varying types of cut to the belly, and sometimes involving no cut to the abdomen at all — the individual would ceremonially reach for a knife before being quickly beheaded. Starrs observes that while misguided Westerners have “naively accepted” Mishima’s seppuku as being “in the best samurai tradition,”[45] it was simply Mishima’s own variation on a theme — the same theme that witnessed hundreds of servile Japanese slit their bellies in front of the imperial palace at the end of the war because of their embarrassment at failing the Emperor. Again, we must question, at a time when we are trying to break free from high levels of social concern and shaming in Europe, whether it is healthy or helpful to praise practices originating in pathologically shame-centered cultures.

As Fuse notes, the traditional European response to seppuku has been disgust, not solely at the physical act itself but because of the servile psychological and sociological soil from which it originates. Because of the difference in mentalities, there is a complication in how concepts such as honor and bravery translate in this particular instance. Seppuku certainly appears to be easier to undertake for a Japanese than for a European. Mishima himself, to give the devil his due, didn’t equivocate in his pursuit of the most brutal methodology. His own wound was found to be five inches across and, in places, two inches deep.[46] Those knowledegable enough in older times would make a cut so as to cut a renal or aortic vein, leading to such catastrophic blood loss that death would be almost instantaneous. Mishima doesn’t appear to have had such knowledge, spilling his intestines out in agony while three successive attempts (by a subordinate and rumored lover) were made to behead him, one opening up a massive wound on his back instead.

Conclusion

The facts surveyed here surely point out the inadequacies of the Mishima Myth as presented in corners of the European Right. I listened again to Bowden’s lecture just yesterday, and laughed out loud at Bowden’s brief gloss of Mishima’s catastrophic childhood (“he was a slightly effeminate child”). Unfortunately, because Bowden spoke more often than he compiled serious research, it’s impossible to determine if Bowden was a conscious promoter of Mishima propaganda, or an earnest but ill-informed believer in the Mishima Myth. I simply don’t know the extent of Bowden’s reading in the matter. Like Durocher, I’ve also watched Paul Schrader’s Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, though I found it to be a cheesy, dated, and rather manipulative hagiography rather than a masterpiece. Durocher comments “You’re either the kind of boy who is challenged, energized, and inspired by this sort of film, or perhaps you’re not a boy,” which I can only regard as laden with irony given that the film’s subject was raised as a girl and once remarked, on being expected to act like a boy: “the reluctant masquerade had begun.”[47] Schrader’s documentary is also highly sanitized; according to Stokes this is due to the tight control that Mishima’s widow and extended family had over the production, and their concern about potential for embarrassment.[48] One small scene showing Mishima in a gay bar was enough for the family to block distribution in Japan, and they even invested money in paying Takeshi Muramatsu to write a 500-page biography, the central proposition of which was to try to convince the Japanese public that Mishima was heterosexual and had merely spent his life, to quote Stokes, “posing as a sodomite.” Rather predictably, the text failed to convince anyone, though it probably salved the family’s pride a little to know that it was out there.

We come back to the central questions of how and why Yukio Mishima should be relevant to us. No answers can be found in the life, politics and actions of a figure not only non-European and profoundly un-fascistic, but who was also strangely un-Japanese. I contend that there is simply nothing genuine to learn from him, and few people who have written in support of Mishima can point to anything tangible beyond the amorphous outlines of the Mishima Myth and a film heavy on style and low on authenticity. There is no single piece of text, no treatise, and no piece of authenticity beyond a final, radically un-European and sadomasochistically-inspired act of self-destruction and death-embracing nihilism. Mishima’s monarchism was servile and parodic, his militarism homoerotic, disingenuous and ludicrous, and his death-as-political-statement was psychosexual and ultimately lacking in logic. Otomo is probably correct in viewing the coup attempt more as a sexually inspired method of “politicising art rather than expressing a belief in ultra-nationalism.”[49]

The question thus arises as to whether associating ourselves with such a figure, surely a clownish homoerotic wignat in today’s vernacular, brings more positives or negatives, both within the Dissident Right and within broader considerations of “optics” or public image. In particular, we should question whether we want to place our politics in a nexus that involves, to borrow the terminology of the Japan scholar Susan Napier, “the interrelationship between homosexuality, politics, and the peculiar form of violence-prone psychosexual nihilism from which Mishima suffered.”[50] I’d argue in the negative.

Members of the Dissident Right with an interest in Japanese culture are encouraged to take up one or more of the martial arts, to look into aspects of Zen, or to review the works of some of the other twentieth-century Japanese authors mentioned here. Such endeavors will bear better fruit. Above all, however, there is no comparison with spending time researching the lives of one’s own co-ethnic heroes and one’s own culture. As Europeans, we are so spoiled for choice we needn’t waste time with the rejected, outcast, and badly damaged members of other groups.

[1] See, for example, Abel, T. (1978). Yukio Mishima: A psychoanalytic interpretation. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis, 6(3), 403–424; Piven, J. (2001). Mimetic Sadism in the Fiction of Yukio Mishima. Contagion: Journal of Violence, Mimesis, and Culture 8, 69-89; McPherson, D.E. (1986). A Personal Myth—Yukio Mishima: The Samurai Narcissus. Psychoanalytical Review, 73C(3):361-378; Jerry Piven (2001). Phallic Narcissism, Anal Sadism, And Oral Discord: The Case Of Yukio Mishima, Part I. The Psychoanalytic Review: Vol. 88, No. 6, pp. 771-791; Piven, J. S. (2004). The madness and perversion of Yukio Mishima. Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group; Cornyetz, N., & Vincent, J. K. (Eds.). (2010). Perversion and modern Japan: psychoanalysis, literature, culture. Routledge.

[2] Ushijima, S. (1987), The Narcissism and Death of Yukio Mishima –From the Object Relational Point of View–. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 41: 619-628.

[3] H. S. Stokes The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima (Cooper Square Publishers; 1st Cooper Square Press Ed edition, 2000), 40.

[4] Ibid., 41.

[5] Ibid., 47.

[6] Ibid., 47.

[7] Ibid., 42.

[8] John Money, Anthony J. Russo, Homosexual Outcome of Discordant Gender Identity/Role in Childhood: Longitudinal Follow-Up, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Volume 4, Issue 1, March 1979, Pages 29–41.

[9] Mize, Krystal & Shackelford, Todd K., Intimate Partner Homicide Methods in Heterosexual, Gay, and Lesbian Relationships Violence and Victims, 23:1.

[10] J. Piven The Madness and Perversion of Yukio Mishima (Westport: Prager, 2004), 2.

[11] Stokes, 43, 44.

[12] Ibid., 44.

[13] Ibid., 58.

[14] Ibid., 61.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] J. Piven The Madness and Perversion of Yukio Mishima (Westport: Prager, 2004), 3.

[18] R. Starrs Deadly Dialectics: Sex, Violence and Nihilism in the World of Yukio Mishima (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1994), 35.

[19] R. Starrs (2009) A Devil of a Job, Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities, 14:3, 85-99, 85 & 87.

[20] Stokes, 103 & 136.

[21] Starrs, A Devil of a Job, 89.

[22] Stokes, 91.

[23] Ibid., 95.

[24] Ibid., 95 & 102.

[25] Ibid., 266.

[26] Ryoko Otomo, The Way of the Samurai: Ghost Dog, Mishima, and Modernity’s Other, Japanese Studies 21 (1), 31-43, 41.

[27] Stokes., 5.

[28] Otomo, 40.

[29] Stokes, 278.

[30] Ibid., 110.

[31] Starrs, Deadly Dialectics, 24.

[32] Otomo, 39.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Stokes., 295.

[35] Ibid., 277.

[36] Ibid., 273.

[37] Ibid., 281.

[38] Ibid., 57.

[39] Ibid., 81.

[40] Ibid., 76.

[41] Ibid., 81.

[42] Starrs, Deadly Dialectics, 7.

[43] Tansman, A. (2009). The Aesthetics of Japanese Fascism. University of California Press, 257.

[44] Fusé, T. Suicide and Culture in Japan: A Study of Seppuku as an Institutionalized Form of Suicide Social Psychiatry (1980) 15: 57, 61.

[45] Starrs, Deadly Dialectics, 6.

[46] Stokes, 34.

[47]Ibid., 48.

[48] Ibid., 267.

[49] Otomo, 40.

[50] Napier, S. (1995). Reviewed Work: Deadly Dialectics: Sex, Violence and Nihilism in the World of Yukio Mishima by Roy Starrs Monumenta Nipponica, 50(1), 128-130.

I remember first reading a short book by Mishima around 1980 (can’t think of the title). I got the impression of someone who believed in a certain type of honor, or pretended to. He also extolled lifting weights, which was gaining traction at that time as a reaction to the self-indulgent 70s. His writing style, as I recall, was lean and spare. I wouldn’t necessarily read Mishima for political content or moralizing but rather for the overall form – the personal texture, compactness, austerity, etc. Certainly, he cut a flamboyant and ultimately tragic figure. I now vaguely remember he described how the act of slicing an apple contained a central truth. He went into quite a bit of detail and exposition on this, maybe along the line that action is more critical for finding the truth than mere words.

Impressive work by DrJoyce. I had no idea about these aspects of Mishima. I’m glad this piece was written.

Excellent reading as always, Prof. Joyce. I am curious if you have seen Andrew Rankin’s “Mishima, Aesthetic Terrorist: An Intellectual Portrait”. This book (I have considered reading it but haven’t gotten to it at this time) apparently features more analysis of Mishima’s essays (as opposed to the fiction), not yet translated into English, thus bringing a new dimension to Western scholarship on Mishima. Interestingly, author Rankin has *also* written a history of seppuku…

I suppose we can attribute some of the glamour surrounding the name of Mishima to the romantic tendency to be attracted to youth and cults of youth (an attitude also commonly associated with fascism); Mishima’s protests against his country’s decadence and the need to return to a previous golden age; his rather spectacular (if not inquired into too deeply) attempt at a coup; and of course his posterity-making suicide. Add in the misunderstood artist angle, and I think we can begin to see the attraction…

I would guess that many of Mishima’s fans on the Right have not studied him at the granular level you have undertaken. Thanks again for this article; I was just upbraiding myself recently for having neglected Mishima for a long time ( I read a handful of the novels when I was young). Perhaps I needn’t be bothered to revisit him at all.

I noticed but didn’t read Durocher’s article at Unz Review. He has always somewhat repelled me, I seldom agree with him, and I came to feel pretty sure he was homosexual. Now I know for certain!

Quote: ‘Piven remarks that there has long been a “Mishima cult” in France (perhaps Durocher can confirm), adding “though his following outside Japan consists largely of gay populations who champion him.”[10] My argument against the Mishima myth is mainly that if key aspects of his biography, including the death, are linked significantly more to his sexuality than his politics, then this is grounds to reconsider the worth of promoting such a figure …” ‘

Couldn’t agree more and I thank you for doing so. It’s good to be reminded every so often of just how sick people can be. Best to be careful.

That was a good takedown of Mishima, inspired by the comments of the article on Unz review no doubt. It does seem that his harakiri style suicide was fetishistic or the fulfillment of some sexual fantasy, rather than honorable or even sensical. I find little to admire in him, but it is good that he left us such a true psychological portrait of himself. He is to be studied, not emulated.

His “troopers” or whatever remind me of certain alt right groups. I do think there is much to admire and model from in Japanese culture though. The books and films of Shuhei Fujisawa for example are entirely high minded.

Try writing a comment without using “mere words. . .”

This essay probably needed to be written. But to any readers who think it seems a little unfair aggressively negative – it is.

The assertion that Mishima “seems hardly political at all” is just silly. It’s true that rightists who read his fiction often find it disappointing. Taken as a whole, his literary oeuvre certainly contains more weird homoeroticism than it does right-wing nationalism. But Mishima also wrote a lot of non-fiction, which was mostly explicitly political. Some titles that come to mind right away are “In Defense of Culture”, “For Young Samurai”, and “Lectures on Immorality”. (These are all my unofficial titles. I don’t think any of them are officially translated.) They are treatments of Japanese political culture, identity, and morality in the post-war era. It’s impossible to tie them to gayness or sadomasochism; they’re obviously sincere. Mishima also took part in debates on campuses during the late 60s student riots (he wrote essays about them too).

Despite the assertion that he became political “in the 60s”, perhaps because he was afraid of growing old – his most explicitly political work of fiction, Patriotism, came out in 1961, halfway through his career, when he was 35. “The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea”, another major midcareer work of fiction, isn’t explicitly political, but very clearly touches on themes of authentic masculinity, loyalty, and patrimony.

“he argued that Japanese right-wingers “did not have to have a systematised worldview,”” I don’t know the context of this quote, or what he said in the original, but it’s actually hard to argue with – especially because Japanese right-wingers have never HAD a systematised worldview. The desire for metaphysical, moral, and/or ideological formal systemization is very European. Prewar Japanese historical figures will often be described as fighting for democracy and human rights in one context and as fierce right-wing militarists in others (Kita Ikki and Toyama Mitsuru come to mind). If Mishima’s assertion bothers you, don’t sweat it – it’s not about you, it’s about the Japanese.

“Mishima is a pale shadow of ultra-nationalist literary contemporaries like Shūmei Ōkawa…” I have to niggle about this. Shumei Okawa is neither literary nor contemporary. He was active in the prewar era only, and I’m unaware of any fiction he wrote. The others you mentioned may be superior to Mishima as ultranationalists but not as men of letters.

As I said, this essay did need to be written – it’s hard to look deeply into Mishima and feel comfortable with Western rightist idolization of him. He was nothing so simple and appealing as le based Japanese samurai man. And it’s true that his life and work was driven greatly by his sexuality. It’s untrue that he was politically insincere or shallow. He was nothing like a European fascist, and he couldn’t be called a traditionalist. Nonetheless, he prioritized the authentically Japanese over the modern or Western; he prioritized the healthy over the sick, and the strong over the weak; and the masculine over the feminine or androgynous. He brought up these themes repeatedly in his writings, fiction and nonfiction.

“Mishima was a profoundly unhealthy and inorganic individual” – this sentence stuck out to me as undeniably true. And I think it’s also true of many other important writers and thinkers. When Nietzsche wrote that wisdom appears on earth as a raven attracted by the scent of carrion, he was doing nothing so simple as attacking wisdom. Blond Beasts rarely write groundbreaking philosophy or provocative fiction; conflicted people who hate themselves and/or the world they were born into do that more. (Nietzsche himself could be described as an unhealthy and inorganic individual, though not to Mishima’s level.) Mishima’s disturbed sexuality and weak, sick childhood were catalysts that forced him to really grapple with masculinity and identity on a personal and intellectual level. When we read about him we should be aware that he was not an ubermensch and that he was a pervert. I don’t see that as reason to dismiss him.

Thanks to both Dr. Joyce for the article and yourself for the qualification.

What a profoundly sick individual. The BBC would have loved him.

I’ve been on 4 continents and from years of life and being around various communities this is what I’ve picked up. Despite an ocean of propaganda promoting Queer behavior, the vast majority of humanity are repulsed by anything touching the topic. Yes, there are crowds at queer parades. So what. A small percentage of any population are weird. Go anywhere and the vast majority are repulsed to hear anything relating to those impaired creatures. It’s not by accident that most queers are in the closet. In all probability, the vast majority of humanity would like to see the males castreted and the females serving society in whore houses… Apparently, to even write about that 0.5% of the population indicates a new trend.

The important thing I noticed and not mentioned in both articles of Dr.Andrew Joyce and Dr. Guillaume Durocher is that their subject studies,( Yukio Mishima) was born in 1925, that’s means that he was 20yo when two atomic bombs erased two Japanese cities from the face of earth, instantly, unexpectedly and irrationally. I think that such a devastating event must have a devastating effect of whatever personality he might be in that critical young and ambitious age, and had a lot to do with what he became in his later years in politics, life style, sexual orientation and general behavior.

Another remark is a comment regarding the portrait of St. Sebastian by Guido Reni: to me, without the absence of female’s breast, this painting can hardly be recognized as a male, the face features, the eyes, the soft skin and the semi-covered private area are all screaming as breast less female! So I don’t know how much it could be added in support of his homosexuality, despite the fact that he is a homosexual.

Finally, I confess that I haven’t read any of Yukio Mishima’s writings or novels, but I think that whatever he was, he was not the one that modeled and shaped by his genetic code, but more with the awkward way of upbringing, the events of 2nd. WW, as well as the traditions and social culture of Japan.

Thanks for the articles.

A sexual sado-masochistic angle certainly explains the Counter Currents fascination. It would be better to contrast Mishima’s private life, politics and death with, say, Romanian patriot C. Z. Codreanu–the latter a much better example for European youth to emulate.

Does the same thing apply to, say, composers? Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky was another tormented soul who eventually killed himself. So, we’re not supposed to like the Nutcracker or Swan Lake. Right? And what about all those male dancers?

Leonardo was gay too. So, the Last Supper is out.

If I’m reading everybody correctly here: we should filter our response to works of music, art and literature through a prism of what we can discover about the author’s sexual nature. He or she must undergo a rigorous background check. How awful and Orwellian. Especially with modern surveillance capabilities, deep faking and internet mob hysteria. I think it’s much better to allow individuals to decide for themselves whether they like something or not. Nothing wrong with examining Mishima’s personal life. That’s normal. But, if I’m reading you all correctly, what you are getting at is worse than Entartete Kunst exhibitions or communist social realism. At least Hitler, Stalin and Mao attempted judgment on the work itself, on it’s merits or degeneracy, not the individual who made it. By focusing on the actual creator you are opening up a pandora’s box of galloping paranoia.

No, it’s not merely that he was gay or that he killed himself, nor is it that we should reject his art. It was the nature of his suicide which probably was a sadomachistic ritual, and his dark psychological underpinnings(cf confessions of a mask) which discount him as a figure of distinction for “the right.” I haven’t read one of his fictional works yet. They may be great.

Basho for example was a fine Japanese poet and spiritual monk who was most likely homosexual, as it was understood at the time. 1600s

i have only read “the sound of waves” and loved, it has that forgotten esence of 19 century adventurous and romantic european writters where courage self discovery and personal growth have a pure reward in the end ,that mixed with the natural way everything develop ,the paused rhytm , the gaze of the island to the outside world stopped in time , their inhabitants like little hobbits not fully divorced from the nature and their colective spirit made me feel really good .

everything feels soo european like a tolkien novel but with more naturality dealing with sex

“Indeed, if one makes the argument that Mishima was in fact a fascist, then one begins to consent to some of the central theses of the Frankfurt School.”

Even if everything that Dr. Joyce says about him is true, it seems pretty plausible that Mishima was a fascist–or, at any rate, that his basic worldview and temperament is much closer to fascism than any other European way of thought.

Though Dr. Joyce does not make any explicit argument on this point, the quoted sentence (in context) suggests the following illogical inference: “If Mishima was a fascist then the Frankfurt School was right about something; since the Frankfurt School cannot have been right about anything Mishima was not a fascist.” In other words, we are invited to believe something not because there is any good reason for believing it but simply because the belief would fit poorly with our political goals or self-image. That’s disappointing. Suppose there is something to the idea that “fascist” politics has some correlation with an unhealthy “authoritarian personality” (or some correlation with homosexuality or sado-masochism or whatever). Well, so what? That might be interesting but it has nothing to do with the truth or rationality of “fascist” politics. Instead of responding to our enemies’ fallacies with fallacies of our own, we should stick to honest argumentation. At the level of facts and reason, they have almost nothing and we have a lot. And if once in a while they’re right about something we should have the courage and integrity to concede this. (Though it may also be worth pointing out that there’s no reason people who want to preserve decent European societies and traditions should think of themselves as “fascists” for that reason alone.)

This is a very superficial treatment of Mishima. I have very little to add to Ryuji Tsukazaki’s devastating remarks above, but I want to note three points:

1. The simple fact that one of the giants of 20th-century Japanese literature was also a man of the Right is worth noting and celebrating, just as we celebrate such artists of the Right as Wagner, Lawrence, and Pound, none of whom lived up to the exemplary moral standards of Ned Flanders.

2. Joyce’s treatment of Mishima’s suicide seems to presuppose the Christian-bourgeois-psychoanalytic attempts to pathologize (as “narcissistic” and “servile”) masculine honor and honor-centered warrior aristocracies who teach men to prefer death to dishonor and hence to commit suicide rather than live in dishonor. In warrior aristocracies, free men lived by the code of death before dishonor, where it is the mark of a servile man to prefer a life of dishonor to death. There was nothing “servile” about Japanese who killed themselves rather than live under Yankee domination.

3. Joyce, despite his year of research, maintains that there is no satisfactory explanation for why people on the Right see Mishima as an interesting writer. There are quite a few articles at Counter-Currents that certainly present a more adequate picture of Mishima’s appeal than Jonathan Bowden’s lecture. You can find a list here:

https://www.counter-currents.com/2019/01/remembering-yukio-mishima-9/

I wish to draw your attention in particular to my review essay on Paul Schrader’s Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters:

https://www.counter-currents.com/2011/01/mishima-a-life-in-four-chapters/

In particular, I would like to quote from the Conclusion, “Mishima’s Legacy”:

In the end . . . what did Mishima’s death mean? What did it matter? What did it accomplish?

It would be all too easy to dismiss Mishima as a neurotic and a narcissist who engaged in politics as a kind of therapy. Right wing politics is crawling with such people (none of them with Mishima’s talents, unfortunately), and we would be better off without them. If a white equivalent of Mishima wished to write for Counter-Currents/North American New Right, we would welcome his work (as we would welcome translations of Mishima’s works!). But we would also keep him at arm’s length. Such people should be locked in a room with a computer and fed through a slot in the door. They should not be put in positions of trust and responsibility.

But Mishima is safely dead, and the meaning of his death cannot be measured in terms of crass political “deliverables.” Indeed, it is a repudiation of the whole calculus of interests that lies at the foundation of modern politics.

Modern politics is based on the idea that a long and comfortable life is the highest value, to be purchased even at the price of our dignity. Aristocratic politics is based on the idea that honor is the highest value, to be purchased even at the price of our lives.

The spiritual aristocrat, therefore, must be ready to die; he must conquer his fear of death; he even must come to love death, for his ability to choose death before dishonor is what raises him above being a mere clever animal. It is what makes him a free man, a natural master rather than a natural slave. It is ultimately the foundation of all forms of higher culture, which involve the rejection or subordination and stylization of merely animal desire.

A natural slave is someone who is willing to give up his honor to save his life. Thus modern politics, which exalts the long and prosperous life as the highest value, is a form of spiritual slavery, even if the external controls are merely soft commercial and political incentives rather than chains and cages.

Thus Mishima’s eroticization of death is not a mental illness needing medication. By ceasing to fear death, Mishima became free to lead his life, to take risks other men would not have taken. By ceasing to fear death, Mishima could preserve his honor from the compromises of commerce and politics and the ravages of old age. By ceasing to fear death, Mishima entered into the realm of freedom that is the basis of all high culture. By ceasing to fear death, Mishima struck a death-blow at the foundations of the modern world.

In my review of Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight, I argued that the Joker is Hollywood’s image of a man who is totally free from modern society because he has fundamentally rejected its ruling values—by overcoming the fear of death. An army of such men could bring down the modern world.

Well, Yukio Mishima was a real example of such a man. And, as usual, the truth is stranger than fiction.

What is “queer coping”?

[I wish Dissident rightists would leave out this kind of non-self-explanatory vocabulary. It’s not quite as awful as the deconstructionist drivel, but it’s getting there.]

Don’t look too deeply into any of your “idols,” for I wager you won’t like what you find!

I knew you could bring Batman into your argument, Greg. But what I don’t understand is why you waited so long in your reply, fourteen paragraphs, to bring it up?

Ryuji Tsukazaki’s remarks are devastating because Joyce’s essay leans so heavily on arguing that “Mishima was a profoundly unhealthy and inorganic individual,” and Tsukazaki argues that such remarks are rather beside the point, because such people are often quite insightful and can make true statements. Joyce admits that his argument is ad hominem. But the argumentum ad hominem is one of the informal logical fallacies.

Tsukazaki also points out that, contra Joyce, Mishima wrote plenty about politics. Indeed, about one-fourth of Mishima’s 43-volume collected works consists of non-fiction, including political statements, and even his writings on literature, art, and culture have political import. Andrew Rankin’s recent book Mishima, Aesthetic Terrorist, is the first book in English to discuss much of this material with an eye to its political and philosophical content. No genuinely scholarly discussion of Mishima’s political import should omit mention of it. Rankin’s book was published in 2018, so Joyce had no excuse not to cover it.

This essay rather blots Joyce’s reputation as a scholar.

“Joyce admits that his argument is ad hominem. But the argumentum ad hominem is one of the informal logical fallacies.”

True, as far as it goes, but here a meaningless observation, for it ceases to be a fallacy when the issue is no longer logic or the quality of an argument, but the man himself, to whit, as a model for Dissident Rightists. This is what I took from Dr. Joyce’s essay. Not that one could not necessary enjoy Mishima’s work, and even see value in it on some level, but that admiration of Mishima the man made little sense within the context of our movement, and, as for admiration of Mishima’s arguments within that same context, there was nothing to admire for they didn’t exist.

Dr. Joyce is quite right to observe that “a movement’s choice of heroes can have an impact on its spirit and ethos.” There was precious little that was described about this man that struck me as anything for our movement to look up to.

Nor did Dr. Joyce’s essay strike me as being a blot on his reputation as a scholar. Disagree with the man if you like, but since such a crack is so demonstrably untrue, the blot, if anywhere, is on yours.

I disagree.

First, there are many things to admire about Mishima as an individual, despite the fact that he was a very weird character: his literary genius, his immense productivity (34 novels, more than 50 plays, countless essays, all before his death at 45), his willingness to spend his prominence in society to buck the liberal democratic trend in favor of the Right, and, yes, his exemplary suicide — because if enough of our people overcame the Christian-bourgeois ethos and were willing to truly prefer death to dishonor, they would make short work of this system.

Second, it is simply wrong to say that Mishima does not offer “arguments.” I suggest you read Andrew Rankin’s Mishima, Aesthetic Terrorist, which is an admirably clear overview of Mishima’s cultural and political worldview. You may disagree with this views, in whole or in part, but it is simply inaccurate to dismiss them as lacking any sort of coherence or argument.

Third, I’ve already pointed out that despite claiming to have spent a year researching this matter, Joyce makes no reference to Rankin or a number of essays at Counter-Currents that actually present a pretty good explanation for why Mishima is a widely read figure in the New Right. I should also mention that there is an entire book on Mishima by the eminent Dominique Venner, Un samouraï d’Occident: Le Bréviaire des insoumis (Paris: Pierre-Guillaume de Roux, 2013) that might have thrown some light on this matter. But, again, there is no sign that Joyce has read it, although it was reviewed at TOO.

I am not going to speculate about Joyce’s motives for such lapses of scholarship.

Fourth, instead of actually reading and citing the relevant sources for understanding Mishima’s status in the New Right, Joyce simply offers what he calls the Mishima Myth. This myth purports to be a summation of New Right discourse on Mishima, but it is nothing of the kind. It is simply an attempt to make this discourse seem maximally vapid, which makes his demolition work much easier. In short, it is what scholars call a “straw man.”

Refuting straw men rather than real arguments is a blot on any scholar’s reputation.

I have read very little of Dr. Joyce’s work, so I don’t know if the lapses of scholarly probity that vitiate this essay are a pattern in his writing. I hope TOO’s and TOQ’s promotion of his work does not turn out to be a bad investment.

I never said Mishima lacked “any sort of coherence or argument.” I said that what I took from Dr. Joyce’s essay was that Mishima had no arguments to admire within the context of our movement. I’d never even heard of Mishima before the other day. But I can recognize a well-supported essay when I read one. Furthermore, since Dr. Joyce was writing an essay about Mishima and not a book, his scope was necessarily more limited, and he spelled out what that scope was in the first paragraph of his essay. He said, “I offer not necessarily a rebuttal or rebuke of Durocher, but an alternative lens through which to view the Japanese author, his life, and politics.” It was a modest goal, appreciated by lay readers like me who had no prior familiarity with the writer in question, but one I thought was well-supported and admirably articulated. Even the commenter Ryuji Tsukazaki that you leaned on so heavily indicated Dr. Joyce had succeeded in that effort, adding — in fact at least twice — that his essay was “necessary.” Furthermore, you have failed to provide any examples of arguments of Mishima’s that would be worthy of admiration or that would even be relevant within the context of our movement.

Instead you prattled on about all this great bulk of political material Mishima had produced. So what? We have politicians who spend lifetimes pouring forth political verbiage while the whole time managing never to say anything at all.

I think your desperation to defend this man supports Dr. Joyce’s point about you. I notice, for example, that over on your own website the other day, in a response to a commenter, you rather contemptuously dismissed Dr. Joyce by informing the commenter that you had posted “a couple of comments” and “that’s about all I can spare his article.” Apparently you dug deep and found you were able to spare some more after all.

There’s another theme of yours I wish to comment on that I find particularly odious. You say that “if enough of our people overcame the Christian-bourgeois ethos and were willing to truly prefer death to dishonor, they would make short work of this system.” Elsewhere you say, “The spiritual aristocrat, therefore, must be ready to die; he must conquer his fear of death; he even must come to love death, for his ability to choose death before dishonor is what raises him above being a mere clever animal.”

That’s nothing but overwrought rubbish. That kind of romanticism about suicide and Osama-bin-Laden-style rhetoric about loving death is an oriental tradition, not an Aryan one. There’s nothing “Christian-bourgeois” about the fear of death. It’s an instinct. Nor is there anything shameful in the fear of death. Indeed, the more of it there is that one overcomes in doing his duty, the more courage he demonstrates. Suicide, except for instances of its practical necessity, such as in the case of Hitler, is eminently an act, and therefore an advertisement of, desperation and defeat.

Indeed, one could argue that the act of suicide is just the opposite of a lack of fear of death. The suicide shows his fear of death precisely in his manifest need to take final control of it.

Furthermore, it’s waste. It is the act of discarding one’s last weapon rather than employing it in the furtherance of one’s cause.

In any case, it is the act of a beaten man. It is not the message our people need. And there are plenty of ways to face and even accept death over dishonor without committing suicide, or admiring those who have done so supposedly for “philosophical reasons,” which it is by no means clear was the motive in Mishima’s case.

White Europeans have been courageously facing and accepting death over dishonor for centuries to the toll of untold millions (unfortunately). The idea that our people need some kind of oriental example to stimulate our willingness to die for a cause is obscene.

This is a list of artists and intellectuals of the Right whose birthdays Counter-Currents more or less regularly commemorates:

January 3: Pierre Drieu La Rochelle

January 3: J. R. R. Tolkien

January 6: Alan Watts

January 8: Anthony M. Ludovici

January 10: Robinson Jeffers

January 12: Jack London

January 14: Yukio Mishima

February 6: A. R. D. “Rex” Fairburn

March 12: Gabriele d’Annunzio

March 29: Ernst Jünger

March 31: Robert Brasillach

April 12: Jonathan Bowden

April 16: Wilmot Robertson

April 16: Dominique Venner

May 13: Julius Evola

May 22: Richard Wagner

May 27: Louis-Ferdinand Céline

May 29: Oswald Spengler

June 13: William Butler Yeats

June 16: Enoch Powell

June 29: Lothrop Stoddard

July 7: Revilo Oliver

July 11: Carl Schmitt

August 4: Knut Hamsun

August 20: H. P. Lovecraft

August 22: Leni Riefenstahl

September 11: D. H. Lawrence

September 18: Francis Parker Yockey

September 26: T. S. Eliot

September 26: Martin Heidegger

September 30: Savitri Devi

October 1: Maurice Bardèche

October 2: Louis de Bonald

October 2: Roy Campbell

October 12: Aleister Crowley

October 15: Friedrich Nietzsche

October 30: Ezra Pound

October 30: Leo Yankevich

November 7: Guillaume Faye

November 15: René Guénon

November 18: Wyndham Lewis

November 19: Madison Grant

November 20: P. R. Stephensen

December 1: Henry Williamson

December 3: J. Philippe Rushton

December 7: Pentti Linkola

December 22: Filippo Marinetti

December 30: Rudyard Kipling

What all these people have in common is not that they were gay icons but that they were eminent intellectuals or artists who were also Rightists. That alone makes them worth commemorating in a culture dominated by the pretense that the Left is intellectual and the Right is not.

If Andrew Joyce were to publish unscholarly hatchet jobs on any of these figures, I would feel duty bound to defend them. So enough about my motives.

Readers are free to speculate about my motives all they want. But the same is true of Joyce’s motives.

A sad, conflicted, and delusional little man, like one or two others we have all encountered. I am reminded of one of the sons of Oscar Wilde, who, in order to repudiate his father’s homosexuality and foppishness, went off in a calculated manner to die in one of Britain’s many wars so as to prove that he was “a real man.” This kind of self-destructiveness ultimately achieves little, and is a poor example to those who follow us. Nonetheless, it can be said that men and women who are internally conflicted often afford us very valuable insights that would otherwise escape us. We can learn from the insights of people like Mishima without celebrating some of his darker impulses and struggles.

“My argument against the Mishima myth is mainly that if key aspects of his biography, including the death, are linked significantly more to his sexuality than his politics, then this is grounds to reconsider the worth of promoting such a figure, already non-White and with no significant Western cultural impact, within the Dissident Right.”

I agree, though with qualifications.

On the other hand, it could also be seen as grounds for reconsidering the worth of the Dissident Right as the exclusive defender of White Interests (c. TOO’s mission statement) and the only viable opponent of Jewish Supreamcy Inc.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but Andrew seems to be denying, or possibly invalidating, or objecting to the link of sexuality and politics. As if seeing a link is somehow self-discrediting. Again, please correct me if I’m wrong.

But, if this is his position, there’s good reason to question it.

Byron points it out in Don Juan in the whole theme of dominance and submission. Fortunately, he takes a cheerful approach to a rather grim topic. One reason, among many, why that poems not only his best, but a world classic and a great masterpiece of European culture. The kind of culture worth fighting and dying for.

In any event, since a large part of my contribution to the comment section of TOO is to point out the difference between the Enlightenment and Romancitism (because, obviously, I think it matters), Byron’s an excellent example of someone who made the move (in Don Juan) from one to the other.

For this reason alone he serves as a power of example for us.

Parasina, The Siege of Corinth, The Prisoner of Chillon, Mazeppa, Marino Faliero, not to mention Cantos III and IV of Childe Harolde all show the Enlightenment side of Bryon’s thought.

Meaning, they’re all political works, ie; works about political tyranny and social oppression. All, without question, worth fighting against (I do not object, entirely, to the Enlightenment or some of the very valid propositions of the Dissident Right; my point is that, if relied on exclusively, they badly distort our situation, and therefore severely limit the range of potential responses to a complex situation).

But in Beppo and also, again, Marino Faliero (where he straddles the fence between both) and especially in Don Juan, Byron fully enters Romanticism, ie; a deeper awareness of the relationship between victim and oppressor, seducer and seduced, and the difficult nature of freedom itself.

In fact, I think that the gradual appearance of fearsome, domineering woman (as long as we’re on the subject of homosexuality, and Right/Left-wing feminized politics) culminating in Prosper Merimee’s Carmen, started with Byron’s depiction of Don Juan’s mother.

Unlike both Mishima and the Dissident Right, Byron (writing 200 years ago!) was able to transcend his Enlightenment assumptions.

And he did it by subjecting those assumptions to the analysis nonpolitical, erotic behavior, especially domination and submission.

And for a reason.

Eroticism is the foundation of political behavior.

I mean, come on. Domination and Submission?

What do you think is the theme of this website?

As I understand it, it’s the justifiable objection to the idea of submitting to the dominance of Jewish Supremacy Inc.

And for a reason devoid of any complexity. We don’t want to be robbed of our lives by submitting to a brutal, stupid, and arrogant force (its intelligence exhausted by its efforts to steal a civilization it did not create, and that it will NOT be able to sustain).

Who could possibly deny that Byron was right?

The point is, though Andrew is certainly on the right track in making a distinction between a healthy and unhealthy response to a personal and cultural crisis (which is what this is all about), his analysis, for all of its depth, breadth and brilliance, ultimately falls short. And the reason, in my view, is because of Andrew’s preference to view this from a Dissident Right perspective.

And this, I respectfully submit, is a judgment made in error.

““Mishima is more a figure of parody than a force of politics,”[43] and attempts to link Mishima with our worldview only provide further grist for the Jewish mill.”

Again, I agree.

But, it’s worth adding that in an age of absurdities, the line between parody and reality is easily blurred.

And JSI’s response to anything only adds to the parody and in no way demonstrates a committment to reality.

“In Suicide and Culture in Japan: A Study of Seppuku as an Institutionalized Form of Suicide, Fuse explains that suicide in Japan essentially originates from a servile position within a highly anxious and neurotic society. Needless to say, this is far from healthy and praiseworthy behavior.”

Says who?

Of course, I agree that it’s important to look at this from the perspective of healthy and unhealthy. But, it’s not enough to leave it at that.

For this reason it’s worth asking the question “Says who?”

An argument could be made that the source of Japanese anxiety and neuroticism comes from exactly what makes their culture one of the most interesting in the world.

Since all of this is ultimately a question of value (as opposed to values, or perscriptions and recipes on how to live) and value is experienced either through some form of eros or agape, it helps to look at it from that perspective.

In this case, what makes Japanese culture so interesting is that unlike China’s Taoist eros and Confucian agape (which exist side by side in greater comfort), Japan’s agape is found in its native religion and its eros in the imported Buddhistic Zen.

The interesting aspect of Japanese culture is that, both the Shinto religion and imported Buddhistic Zen force, or reinforce, the individual out of explanatory behavior all together.

Shintoism’s whole concept of spiritual energy, is that whatever significance or meaning life has is derived, not from life itself, but from its kami and from the use men put to it.

This shows a striking similarity to American Pragmatism, expressed best in G.H. Mead’s statement that the meaning of a sign is the response to it; and that that meaning is given greater significance by how it is used in a specific context.

The idea that life in itself has no meaning and never did, and that the only meaning it could ever have comes from us and not some divine or “natural” source, religious or political, is a position very few have come to accept.

In any event, this accounts for the intense immediacy of Japanese cultural responses, especially in times of crisis.

It’s also why it truly is an insult to them, one to which they respond to with justified indignation and even contempt (rightly so) that they are simply unoriginal imitators. When, in fact, whatever they do imitate, they transform.

Still, it is true that no tranformation takes place until something is innovated that they can, eventually, transform.

Anyway, though I’m giving an incomplete picture, as I always do in these extempore comments written on the fly, the important point here is, that in times of crisis, personal and/or cultural, the idea that life is only given meaning by our responses to it truly comes to the fore and leaves people without any real cultural support for their decisions and actions. You’d have to have a strong spirit, rich personality, and well-informed mind to respond at all adequately. And that’s the case today now more than ever before – ever. And most just can’t do it. So they fall back on an already existing position, or fall through the cracks all together.

The result is a devastating personal and cultural incoherence, especially if one has had a bad childhood filled with abandonment, rejection, abuse and neglect.

Or, if one is the member of a racial group that is being scapegoated on a global scale.

In either case, this culture crisis and social incoherence is literally everywhere.

I mean, just look around.

The main point for me regarding Andrew’s excellent essay is that what all of this boils down to in the end is our ability to respond to a severe culture crisis, and that Mishima responded in a way that was not at all healthy.

And not just Mishima.

Perhaps one solution, for us at least (and that’s who I’m primarily concerned about) is to let each other know that, though we might think differently, we have each other’s support, and, for that reason, aren’t alone.

There are certainly some interesting and profitable aspects to the conversation generated here in the comments. I continue to be encouraged by the caliber of readers visiting here.

I do think some slippage has been introduced into the discussion however. It seems that the kernel of the Herr Doktor’s argument was cautionary as it related to enshrining Mishima as a hero. He seems to be concerned that allowing Mishima into a Rightist Pantheon will ultimately be destructive, rather than constructive. Just offhand, Mishima’s apparent disgust with children and women might be a concern, given that White birthrates and population ratios are of interest to us.

Joyce writes that an inquiry: “…lead(s) to the conclusion that Mishima was a profoundly unhealthy and inorganic individual who should be regarded as anathema…”.

What I think Dr. Joyce is doing is to examine whether we gain or lose if we grant cultural hero status to Mishima. I don’t think he is critiquing the writings of Mishima, and he certainly doesn’t seem to be telling anyone that they can’t enjoy reading Mishima.

The comments about dismissing works of art due to attitudes the creators had, or the suggestion that Joyce insists that we need a litmus test for evaluating art that considers the creator’s moral virtues or failings seem a bit off-base here. That would indeed be simple-minded overreach, the kind that gave us conductors who refused to perform Wagner because he was “anti-Semitic”.

I would guess Dr. Joyce had our younger comrades in mind when he wrote this article; he obviously cares about what kind of men we promote as heroes *based on the lessons that figure’s life suggests for emulation*. In this, Dr. Joyce is being sensible and, I think, entirely reasonable.

I also believe we can enjoy the fruits of creativity regardless of the presence or absence of laudable character traits in the person who created them. I would bet that Dr. Joyce believes that as well.

I’m a new fan of some of Mishima’s writings, and am not familiar with the intellectual scene associated with the European far right, but amongst other groups that admire Mishima, I’ve never been under any impression he is regarded as a saintly fount of virtue, a beacon of conventional psychological health, or a literal role model to emulate. Indeed, he was clearly an extremely disturbed, unhappy, neurotic figure who nevertheless channeled his darker impulses into something like artistic genius.

If the far right can’t separate an evaluation of a thinker’s psychology from their philosophical or artistic output, this speaks far more to the intellectual shortcomings of the current far right than to the worth of any particular cultural icon. I utterly reject the false dichotomy that I must either idolize a figure as worthy of emulation, or else reject their work entirely on account of neurosis or (alleged) lack of virtue. And I respectfully question whether Joyce’s proposed “Dissident Right” is the exclusive defender of white, European interests.

In the future, I hope Dr. Joyce will publish more about his philosophy behind the criteria by which he advocates judging European Far Right cultural heroes. I also hope to know more about his philosophy of the Dissident Right, and how it specifically differs from, and why he considers it superior to, simply advocating for “white genetic interests” without attaching a separate, more extreme ideological and political agenda. What about those of us who simply care about white people, and don’t agree with Dr. Joyce’s hostility towards homosexuals?