Hemingway’s Truth (and Ours): A Consideration of “Across the River and into the Trees” and What It Implies

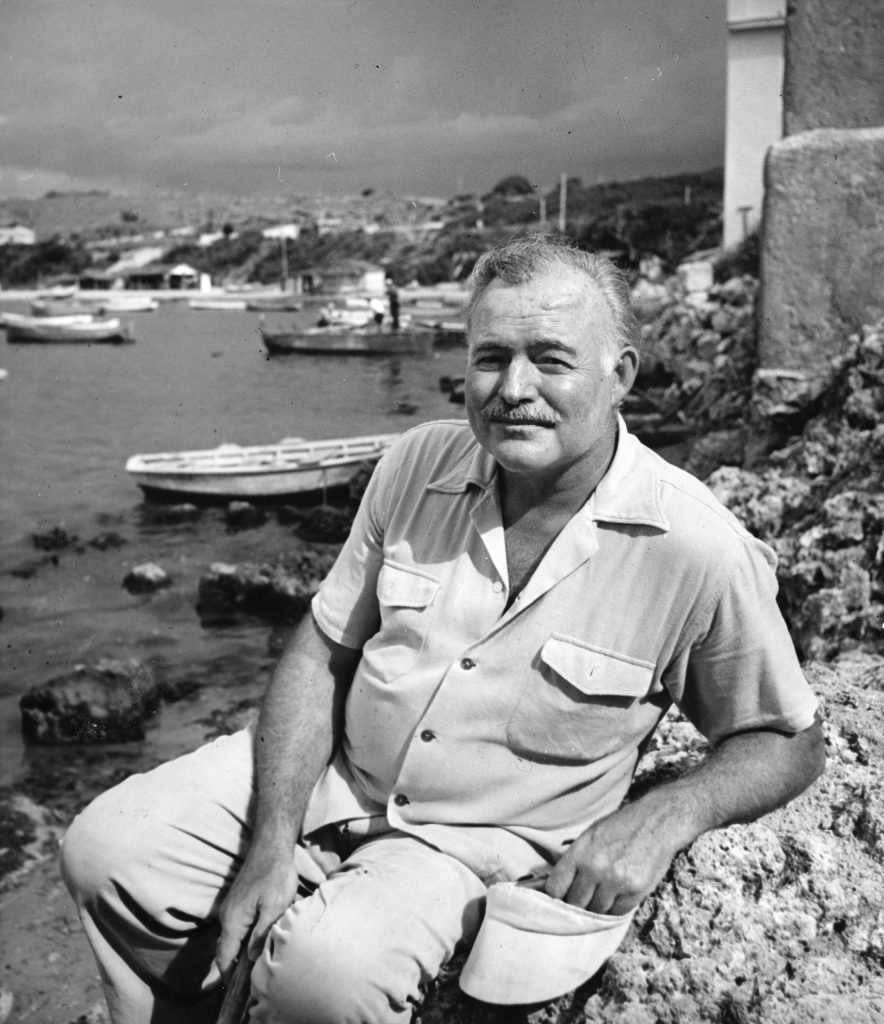

Hemingway circa 1950, when he wrote Across the River and Into the Trees.

My take on Ernest Hemingway is that, first and foremost, he wrote from a journalistic perspective. That is to say, he sought to tell the truth about what is going on in particular situations and with particular people, whether real or fictional. Right out of high school, he got a job as a cub reporter for the Kansas City Star newspaper. They gave him a manual of style to follow—use short sentences, eliminate every superfluous word, avoid adjectives—and he took it to heart and stuck to it for the whole of his writing life.

Hemingway was at heart a reporter. He wasn’t trying to be arty, dazzle you with his prose, entertain you, put things into a context, philosophize, advocate, or moralize. He was attempting to depict the truth about singular, here-and-now, experienced reality—things and people, actual and imagined.

Bullfights and A Farewell to Arms, it was the same challenge to Hemingway. There he’d be, early in the morning, standing at his desk (standing was better for his bad back), doing his level best to write the truest, most accurate, sentence he possibly could, the one that best captured the reality of a moment. When he was satisfied with that sentence, he went on to the next one, and the next one and the next one and the next one. He worked incredibly hard at it, and he was exceedingly good at it.

For me as a reader, Hemingway has been a mixed experience. I read him and respond, “Yes, that’s the way it is, that rings true to me, and it’s fundamental, basic, it really matters for something. He’s showing me what it is like, what he or she is like, at this instant. And that’s good, and that’s why I keep coming back to his writings.”

But truth isn’t equated with depth. Despite the “iceberg” talk—all the submerged meanings that are supposed to be there beneath Hemingway’s simple, declarative sentences, for me he stays on the surface of things; no iceberg, or not much of one. Something can be true without being complete or profound. She shot him (“The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber”). Or did she? Has Hemingway taken me deep enough to discern why she did whatever she did? Maybe not.

But then again, maybe it doesn’t matter. Maybe it’s my problem to think I have to probe beneath the surface of things and articulately figure it all out. Oscar Wilde said that the secret of living a rewarding life is to stay on the surface of reality. For Hemingway, that could mean writing today’s sentences describing the struggle of an old fisherman to reel in a marlin and then going out on his boat and doing some marlin fishing himself. For me, it could mean writing this up about Hemingway and then watching an old French New Wave film. Do it because for whatever reason it’s there and you feel pressed from within to do it. Quit trying to understand it, because if you do that you’ll come up with reasons to do it half-assed or later.

It would be nice to have a richer aesthetic experience reading Hemingway’s fiction, and to be caught up in a story with twists and turns that keep me postponing bedtime, but that doesn’t happen for me with him.

Bottom line, while I like Hemingway’s oeuvre, I’m not bowled over by it as I know many people are. At this writing, Ken Burns’ Hemingway-exalting three-part series was recently on PBS, and I just read a memoir—Dad’s Maybe Book—by the highly regarded contemporary American writer Tim O’Brien, who idolizes him. I respect Hemingway very much, but connect with his Noble Prize greatness? I’m not there.

* * *

This week, I read Hemingway’s 1950 novel Across the River and into the Trees with my usual reaction: good but I wanted more. Although, I must say that re-reading the book and thinking about it for this writing, I’ve found significantly more in it to like and admire. That has helped me realize that a lot of my reservations about Hemingway come from my inability to engage him at the level he deserves.

This week, I read Hemingway’s 1950 novel Across the River and into the Trees with my usual reaction: good but I wanted more. Although, I must say that re-reading the book and thinking about it for this writing, I’ve found significantly more in it to like and admire. That has helped me realize that a lot of my reservations about Hemingway come from my inability to engage him at the level he deserves.

The book takes place in Italy after the end of WW II. Richard Cantwell, the central protagonist, is a fifty-year-old U.S. army colonel. The book is about Cantwell (can’t well?) going duck hunting, getting a physical exam from his doctor, and engaging in mawkish lovey-dovey talk with Renata, his 18-year-old Italian girlfriend and regaling her with his exploits and opinions with reference to World Wars I and II. The book is largely conversations between the two of them with Cantwell doing most of the talking. Typical of Renata’s side of it:

“I love you,” the girl said. “I love your hard, flat body and your strange eyes that frighten me when they become wicked. I love your hand and all your other wounded places. Tell me about Paris, please”

Hemingway in WWI.

Cantwell is more than up for obliging her. He tells her about fighting with the Italians in WWI (Hemingway was an ambulance driver for the Red Cross in Italy during that war), taking Paris, Normandy, the battle of the Hurtgen Forest, and his views on generals Eisenhower, Patton, and Rommel (Hemingway was a war correspondent during WWII). He is bent on referring to Renata as “Daughter.” I assumed it was akin to Hemingway’s desire in real life to be known as “Papa,” kind of putting himself one-up. There’s a lot of sex talk by both of them, but it isn’t clear how much carnality is actually happening, or how much either of them really wants it or, in Cantwell’s case, is up to the task, if you’ll pardon the expression. Through it all, I had the distinct feeling that I was being set up for Cantwell’s imminent demise, and sure enough, at the end he knocks himself off in the back seat of a chauffeured luxury car—or so I thought; more on that later.

Did Across the River and into the Trees ring true to me? Yes, it did. Especially now that I’ve reached antiquity, fifty doesn’t seem all that old. But nevertheless, I bought the idea that Cantwell thought he had played out the string in his life. He was still up to hunting ducks proficiently, but that was about it. Apart from whether or not he could still pull things off, the world wasn’t anywhere near as enthused about him as it once was. Case in point, he’d been demoted from general to colonel. I flashed on the title of the late comic actor Charles Grodin’s memoir, It Would Be So Nice If You Weren’t Here. I could personally relate to being relegated to playing bit parts—if that—in life’s movie.

The truths being offered up to me in Across the River and into the Trees seemed to include what Hemingway wished were so about himself but weren’t—a full-fledged fighting man rather than an ambulance driver and news reporter, that sort of thing. At the time the book was written, Hemingway was fictional character Cantwell’s age and gaga over a 19-year-old beauty named Adriana Ivanich he had met on a trip to Italy. From what I can tell from reading biographic accounts, Hemingway’s feelings weren’t reciprocated, and judging by the portly look of him in pictures taken at that time, it is highly unlikely that Adriana would have swooned over his “hard, flat body.”

Hemingway with Adriana Ivanich, who was the real-file counterpart to the Renata character in Across the River and Into the Trees.

Did I like Across the River and into the Trees? To the extent I like any of Hemingway’s writing, yes. I’d give it four stars out of five, and consider it to have been a decent enough use of my time. What I most respected about the book was the care Hemingway put into writing it. I’ve read critics’ contentions that he knocked it out, getting antsy about not having produced a novel and the money that comes with it since For Whom the Bell Tolls a decade before. Not so. Hemingway slaved over this book, I’m sure of it.

I don’t consider Across the River and into the Trees a major literary accomplishment, so why am I putting energy into writing about it? It’s 11:51 p.m. and I’ve been spent all day typing this up, and I’m far from done. It’s because after I finished the book I did what I often do with books and films, cruised the internet reading what other people, including scholars, have said about it and it hit me that if the people I read are right, I misread the book’s plot in a big way, and that intrigues me. I’ll spend the rest of this writing going into that.

* * *

I thought Cantwell committed suicide in the back of the car, shot himself with one of his shotguns. But no, he had a heart attack. Wikipedia says that, every reviewer and academic I read says that; those SparkNotes-type books say that. And not only did I miss the ending, all sorts of other things got by me, such as I didn’t pick up that Cantwell had a bad heart condition.

Here are some examples of what I read about Across the River and into the Trees that don’t square with what I took from the book:

[A] flashback to a physical examination that the colonel took three days earlier, when a skeptical army surgeon allowed him to pass even though both men knew the colonel to be dying of heart disease.

[Cantwell] goes by boat to the Gritti Palace Hotel and, once settled there, dines with his young mistress, Countess Renata. Afterward they make love in a gondola on the way to Renata’s home.

In the end Cantwell dies of a heart attack in his car, shortly after he reminds his driver of the dying words of Stonewall Jackson: “Let us cross over the river and rest in the shade of the trees.”

After repeating General Stonewall Jackson’s final words, he moves to the back seat of the Buick and firmly closes the door. Jackson [the driver] finds him dead shortly thereafter and reads a note that the colonel had written minutes earlier ordering that the portrait and his shotguns be sent to the hotel for Renata to claim.

What heart trouble? From the book:

“Wasn’t my cardiograph O.K.?” the Colonel asked.

“Your cardiograph was wonderful, Colonel. It could have been that of a man of twenty-five. It might have been that of a boy of nineteen.”

Cantwell had a blood pressure issue, which a lot of people have, including me, and I wouldn’t call that a heart problem. He was taking mannitol hexanitrate for his blood pressure. I take lisinopril, but no doctor is telling me that I have a heart problem.

Cantwell’s doctor was concerned about his head not his heart.

“How many times have you been hit in the head?” the surgeon asked him. “Concussions, any time you were out cold or couldn’t remember afterwards?”

[Concussions were a big concern around Hemingway. There’s much speculation that they were causal in his suicide.]

“Maybe ten,” the Colonel said.

“You poor old son of a bitch,” the surgeon said.

“[T]hey make love in a gondola on the way to Renata’s home,” so I read online. There’s nothing that definitive about their love life anywhere in the book. With them, maybe there’s consummation and maybe there isn’t, with the reader left to make that call.

Negative reviews of the book scoff at the idea of a young girl being turned on to an old coot like Cantwell. Implausible? Really? A senior military officer, a participant in the central historical events of the age, wicked eyes, wounded places, and a hard, flat body? A chiseled, weathered older man, strong, a father figure? No? Are you sure? Is fifty that old? Brad Pitt is 57 and I can imagine a 19-year-old being more than a bit interested in a gondola romp with him.

I kept reading about what a big flop the book was. True, it wasn’t a critical success, though it had its defenders at the time it was published, and over the years esteem for the book has risen. While I’m not jumping up and down cheerleading for the book, I take it seriously as a literary work. A film based on the book is currently being produced, so it’s stayed in the public consciousness after seventy years. And it was a popular success. It spent seven weeks at the top of the New York Times best-seller list. And it was a commercial success, selling more copies than any other Hemingway book up to that time.

Hemingway in WWII

As for the ending, it sure seemed to me reading the last pages that it wasn’t Cantwell’s heart that had given out. Rather, his life has given out, and he was going to end it. I thought about how a decade later with a shotgun blast to his forehead, Hemingway had ended his own life. In Across the River and into the Trees, Hemingway is foretelling his own death, that was my impression.

Here are passages near the end of the book. There should be some ellipses in this, but I’ve decided they are distracting, so I’ve left them out.

“Turn left,” the Colonel said.

“That’s not the road for Trieste, sir,” Jackson [his driver] said.

“Don’t you point me out a God-damn thing and until I direct you otherwise, don’t speak to me until you are spoken to.”

“Yes, sir.”

“I’m sorry, Jackson. What I mean is I know where I’m going and I want to think.”

You are no longer of any real use to the Army of the United States. That has been made quite clear.

You have said good-bye to your girl and she has said good-bye to you. That is certainly simple.

Just then it hit him as he had known it would since they had picked up the decoys. Three strikes is out, he thought, and they gave me four. I’ve always been a lucky son of a bitch. It hit him again badly.

He reached into his pocket and found a pad and pencil. He put on the map-reading light, and with his bad hand, printed a short message in block letters. “Put that in your pocket, Jackson, and act on it if necessary. If the circumstances described occur, it is an order.”

“Yes, sir,” Jackson said, and took the folded order blank with one hand and put it in the top left-hand pocket of his tunic.

“Jackson,” he said. “Do you know what [Southern American Civil War] General Thomas J. [Stonewall] Jackson said on one occasion? On the occasion of his unfortunate death. I memorized it once. I can’t respond for its accuracy of course. But this is how it was reported: ‘Order A. P. Hill to prepare for action.’ Then some more delirious stuff. Then he said, ‘No, no, let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees.’

“Pull up at the side of the road and cut to your parking lights. Do you know the way to Trieste from here?”

“Yes, sir, I have my map.”

“Good. I’m now going to get into the large back seat of this god-damned, over-sized luxurious automobile.”

That was the last thing the Colonel ever said. But he made the back seat all right and he shut the door. He shut it carefully and well. After a while Jackson drove the car down the ditch and willow lined road with the car’s big lights on, looking for a place to turn. He found one, finally, and turned carefully. When he was on the right-hand side of the road, facing south towards the road junction that would put him on the highway that led to Trieste, the one he was familiar with, he put his map light on and took out the order blank and read:

IN THE EVENT OF MY DEATH THE WRAPPED PAINTING AND THE TWO SHOT GUNS IN THIS CAR WILL BE RETURNED TO THE HOTEL GRITTI WHERE THEY WILL BE CLAIMED BY THEIR RIGHTFUL OWNER SIGNED RICHARD CANTWELL, COL., INFANTRY, U.S.A.

“They’ll return them all right, through channels,” Jackson thought, and put the car in gear.

And that’s the end of the book. Where’s the heart attack death? It seems like a suicide to me. Really, the book is much stronger, and makes more sense, as the depiction of someone who isn’t in the game anymore and is left chattering on to a young girl of another generation who really doesn’t connect to what he is talking about. The battle’s over. Go into the trees and rest. I can relate to that sentiment, that impulse. It’s a true one.

The main point I want to make here, however, comes out of the fact that my experience of Hemingway doesn’t square with the word that comes down to me about him. When I take him in with my senses—in an immediate, experienced way—he comes off as a highly capable and dedicated, though not particularly informed, insightful or wise, writer and a hard worker, but no huge deal as an artist. This week, I read his Paris memoir, A Moveable Feast—same conclusion. Even the plot of Across the River and Into the Trees isn’t what the experts tell me it is. And if Hemingway isn’t what the mediators of reality—the people who do the talking and writing and show me pictures and tell me stories—say he is, what else isn’t what I’ve been led to believe it is?

Recently, I wrote an article that set out a possible defense of White Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin convicted of murdering Black George Floyd during a May, 2020 arrest. I assumed Chauvin was guilty of something, it was just a question of the extent of his culpability, but writing up the article, it hit me, I’ll be damned, the guy is arguably innocent of the charges against him! I had accepted uncritically what I had been told and shown about the case (the big thing, the cell phone video of Chauvin with his knee on Floyd’s neck and the media’s interpretation of it). It came home to me, and this Hemingway writing gets at it, that we all need to think things through for ourselves and come to our own conclusions and not just run with whatever people with a public platform put in front of us. And that means everybody with a public platform, public voice, including the writers for this magazine and me right now.

You’re more interesting than Ernest. Thank you.

Hemingway wasn’t a fighter in any war; generally lost boxing matches he forced on acquaintances, and wasn’t recruited when he offered his sorry services as a Soviet spy. I don’t know if that gets him across the river, but it definitely leaves him in the shade.

Don’t knock ambulance driving until you’ve tried it. It provides experience you get nowhere else. I served collateral duty as an EMT (Intermediate) and wouldn’t trade what I learned about myself and others. The conscientious don’t avoid action.

Al Pacino’s performance as blind by his gasconade Marine and bon vivant, in a moment changed a tango partner’s life forever. Women see things. Writers and dogs teach me things. Cellared varietals deserve decanting, breathing.

Yesterday, despite a remarkable heat wave there was a carnival atmosphere of good will everywhere we went. Everyone mocked the President and the Governor. It may be getting even hot air after months of rebreathing yet hotter air. You have a public you owe in-person on Dr. Pierce and others. You might even like it. My young wife loves Mark Weber’s friends and guests over food. We need it.

You know who Hemmingway was? A God Damn Bolshevik.

With the single sole exception of Bob Dylan, Hemingway was the most adored self-publicist who ever was. His I.Q., I submit, was as abbreviated as his dehydrated “prose.”

Have you seen an Alan Rudolph film called “The Moderns”? It’s worth a look if you haven’t. It is set in the avant-garde art scene in Paris in the mid-1920s. Among other things, the film deliciously lampoons Hemingway as a wannabee writer who spends most of his time cadging drinks at Harry’s New York Bar.

You might say that the film does for (and to) Hemingway what Aristophanes’ “The Clouds” did for (and to) Socrates—but with infinitely more justification.

And WHAT was the Issue of this Narrative ?

NOTHING !

May be some bits about Your own Health problems and lack of life..

Every experienced man knows .. of own experience …that from 50 to 60 a man is at his TOP’

regarding almost anything a man wants … and that includes Women

I mean for REAL MEN .. not some Pussies

I havent read Hemingway as I am disgusted by what I have read about him

and Your attached Pictures confirm my suspicions

A Pot bellied old Narcissist … trying to re-create himself

on the line of a Casablanca Joe ……

Nothing SERIOUS to remember there…

I haven’t read your particular take on Hemingway before, but I think it has merit. I enjoyed Hemingway, especially For Whom the Bell Tolls, as a teenager, but was scared off Across the River… by the very belittling review I read in the 1950 Time Capsule back in the 70s. Remember them? They were condensed versions of a full year of Time Magazine for various years that were considered noteworthy, like 1923 (Time’s first year of publication), 1929 (stock market crash), 1933 (Hitler & FDR), etc., packaged in a glossy, soft-cover format. About 10 years ago I finally got around to reading Across the River…, & thought it was OK – not great, but it did ring true. Btw, one plausible reason for Renata’s interest in, or affection for, a much older US Army colonel in immediate post-WWII Italy is that the Americans were just about the only ones with money, & guaranteed access to food. Italy (& almost all of the rest of Europe) had been ruined by the war. My impression was that Renata’s upper class family probably lived in genteel poverty, at best.